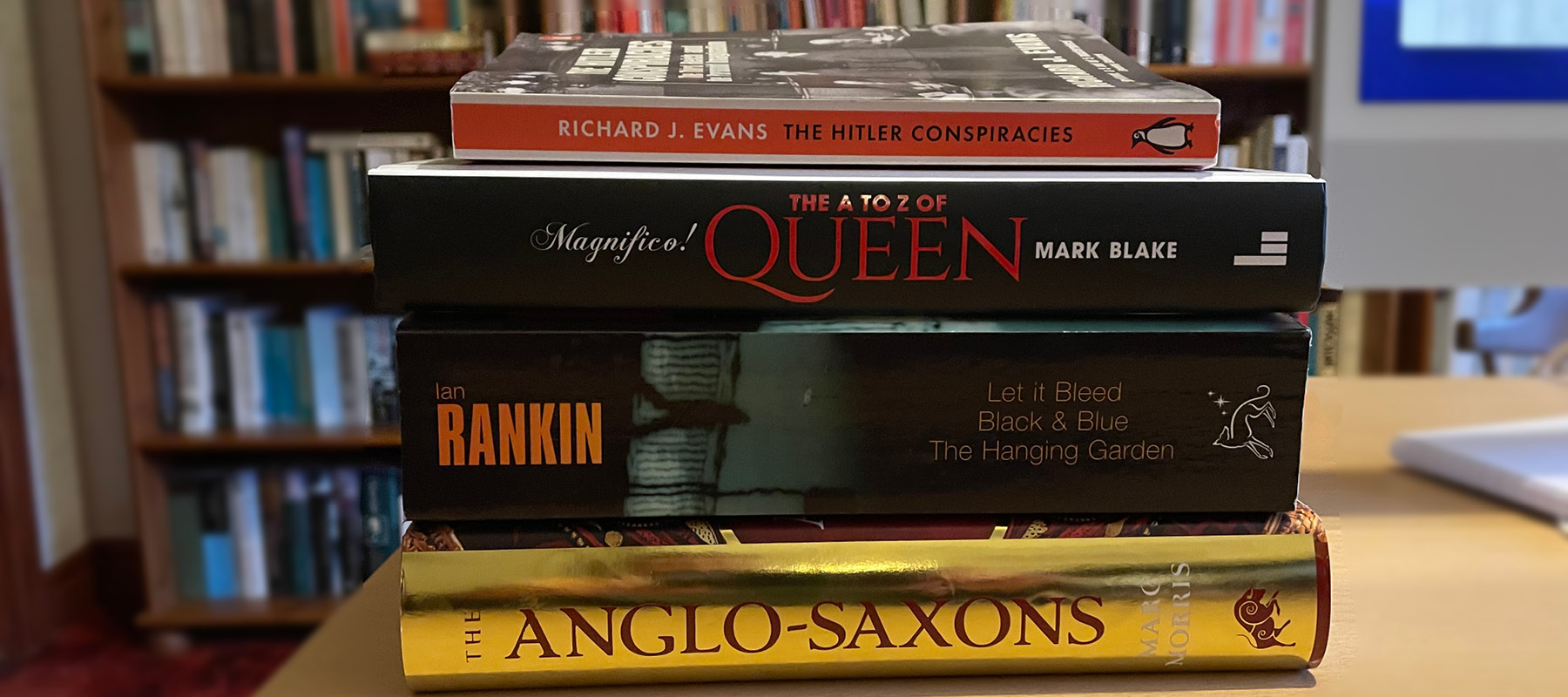

Books, TV and Films, December 2021

6 December

My Inspector Rebus reading journey has arrived at The Hanging Garden, originally published in 1998 and the final part of a three-book omnibus edition called The Lost Years.

The main plot line concerns an ugly turf war between rival gangsters. Hello again, ‘Big Ger’. One of the great things about following the Rebus trail is the cast of recurring characters. Big Ger is still doing time and his ascendancy is threatened by the not-at-all-pleasant Tommy Telford. Rankin takes us to even uglier places than usual (and not in a sightseeing sense) and the book doesn’t pull its punches in its portrayal of graphic violence, including the torture of Rebus himself. There is also a nice Brian de Palma, Untouchables-esque set piece involving a planned armed raid on a top-secret pharmaceutical factory.

As ever, there are several sub-plots in play — here involving Nazi war crimes in France, the Bosnian and Chechen conflicts (major news stories at the time Rankin was writing) and the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Atrocity is the underpinning theme, and Rankin wrestles with questions about how we reconstruct the past and the extent to which time can wash away responsibility for crimes and misdemeanours committed long ago.

Rankin uses Rebus’ strained relationship with his brother (brought together by a hit-and-run involving Rebus’ daughter) not just to add depth to the backstory but also to probe into the relationship between history and memory. Brother Mickey shows Rebus his collection of old postcards and photographs sent to him by Rebus during the latter’s time in the British army — extant documents, ‘proof’, it seems, of a happy and carefree younger life.

And here were these postcards, here was the image of Rebus’s past life that Mickey had lived with these past twenty-odd years.

from Ian Rankin, The Hanging Garden

And it was all a lie.

Or was it? Where did the reality lie, other than in Rebus’s own head? The postcards were fake documents, but they were also the only ones in existence. There was nothing to contradict them, nothing except Rebus’s word. It was the same with the Rat Line, the same with Joseph Lintz’s story.

Click here for my comments on Black & Blue.

Click here for my comments on Let It Bleed.

12 December

Questions of truth and accuracy are also very much at the heart of The Hitler Conspiracies: The Third Reich and the Paranoid Imagination by Richard J Evans. Regular readers will know how much I admire Evans. Comparing him with the historian Peter Padfield, I have written that Evans “is opinionated, frank (read his obituary of Norman Stone) but also authoritative. Unlike with Padfield, the reader feels in safe hands, confident that the text distils knowledge and understanding built up over a lifetime of study.”

The book is organised around five topics: the notorious antisemitic publication called The Protocols of the Elders of Zion; the stab-in-the-back myth after 1918; the Reichstag Fire in 1933; Rudolf Hess’ flight to Britain in 1941; and the fate of Hitler in 1945.

For those with knowledge of the Nazi period, these are all well-known issues and ‘mysteries’ — indeed, the final chapter about what happened to Hitler is so much a staple of modern culture that it is probably familiar even to those with little or no knowledge of German history — and Evans deals with them all in his usual thorough and judicious way.

For me the most interesting parts of the book were the bits in which Evans draws out more general lessons about what he terms ‘the paranoid imagination’ — conspiracy theories and ‘conspiracists’ (ie people who believe in a conspiracy theory or theories and not to be confused with ‘conspirators’, people engaged in a conspiracy).

He talks, for example, of a widespread refusal to recognise reality. This is not as ridiculous as it first sounds, when the very idea of objective facts and empirical verification is under sustained assault: consider the fact that vast numbers of Americans still refuse to accept that Joe Biden won the presidential election in 2020. What matters in the paranoid imagination is not whether the facts themselves are true but the ‘essential truth’ that lies beneath. Again, if that sounds absurd, consider an article written by the Daily Telegraph‘s Camilla Tominey about the BBC in December 2021 in which she introduced an anecdote with the words: “This might not be true but it certainly is believable.”

In the interests of clarity, the quote is from a tweet in reply to Tominey from the BBC’s Nick Robinson, a presenter on the Today programme (and someone, incidentally, with a background in Conservative politics). The Telegraph article itself is behind a paywall and the only such freely visible phrase is “It may be apocryphal but it is a story worth telling anyway.” Either the previously quoted words appear behind the paywall or the sentence itself has been amended. Robinson’s tweet says:

Today we learned that you don’t think facts should get in the way of attacking the BBC. You start by saying so: “This might not be true but it certainly is believable”. You say Today cancelled an interview with John Redwood. Listeners heard him in our most prominent slot at 810 [sic]

A tweet from Today presenter Nick Robinson in reply to Camilla Tominey

These and other lessons that Evans draws — another is how myths become so embedded that they can no longer be discredited by facts and morph into unchallengeable truths — are as pertinent in the modern day as they are to the student of Nazi Germany.

Click here for my comments on Peter Oborne’s book The Assault on Truth.

17 December

And what happens when we have mere scraps of evidence about events in the past, especially when the history in question is particularly contested and entangled with fundamental questions of identity and culture — the foundation of a nation, for example?

Our understanding of the Anglo-Saxons must ultimately rest on the historical sources, but for most of the period these are extremely meagre. For the first two centuries after the end of Roman rule, we have virtually no written records of any kind, and are almost entirely reliant on archaeology. The situation improves as the period progresses … but there are still huge gaps in our knowledge.

from Marc Morris, The Anglo-Saxons

About ten years ago, determined to educate myself about the period of history I then referred to dismissively as the Dark Ages, I came out of Waterstones with a copy of a paperback brick called Anglo-Saxon England by Frank Stenton. I am guessing that it was the only such general history on the shelf because — caveat emptor! — I foolishly bought it based on little more than a glance at the puff-quotes on the cover. Alas, it did not take long to twig that this was not just a rather worthy old book, published in 1943, but the relevant volume in the venerable but decidedly creaky Oxford History of England series. (AJP Taylor’s wonderful but very dated English History 1914–1945 is part of the same series.)

That’s why I love books like The Anglo-Saxons, written by Marc Morris and published just a few months ago. Morris is another of a group of eminently readable historians I wrote about when discussing Powers and Thrones by Dan Jones. The Anglo-Saxons is an excellent introduction to this period of English history and doesn’t require any prior specialist knowledge or skills beyond an ability to keep track of (or, in my case, note down) the neverending list of people whose names begin with ‘Ælf-‘ and ‘Æthel-‘.

Morris provides an excellent insight into how historians work and the judgements they make. Take the chapter about Offa, for example, the eighth-century Mercian king. Within the space of a few pages we read numerous phrases along the lines of: “He claimed … but this may have been just a fiction to boost his credentials”; “Given that … Offa must have been…”; “It looks as if…”; “The outcome of the battle is not recorded, but it was almost certainly a defeat for Offa…”; ‘Other sources suggest that…”

Morris introduces us to the main historical themes and issues relating to the period, where current research is at and how historians’ thinking has evolved. We repeatedly meet statements saying something like ‘Historians generally used to think that … but now…’. For example, he guides us through the question of who was actually responsible for building Offa’s Dyke, the reasons why it was constructed, how it might have been done and how long it would have taken. We learn that an extensive investigation of the earthwork between the 1970s and the early 2000s concluded that Offa’s Dyke was not nearly as long as had always been assumed and that it did not in fact run from sea to sea, as Asser (a ninth-century bishop who wrote a life of King Alfred) had written. Then we learn that this new interpretation “has lately been called into question” and that Bishop Asser may have been right all along.

And then there is the discussion of Alfred the Great, co-opted in recent years as a figure central to English identity, the hero-king who drove the Vikings into the sea and created the English nation (and burned the cakes). Again, the actual picture is much less clear. The myth of ‘Alfred the Great’ was an invention of the eighteenth century: “attitudes that were deemed praiseworthy and patriotic in the Georgian and Victorian eras were being projected back onto a distant ninth-century king.” The first surviving record of the appellation ‘Great’ is not until the thirteenth century (unlike the mighty Charlemagne who was ‘the Great’ in his own lifetime). He almost certainly didn’t burn any cakes either.

Rather like well-written historical fiction, though for different reasons, books like The Anglo-Saxons are a gateway to more serious study of a historical topic, theme or period. Now I feel ready to tackle Stenton afresh.

Click here for my comments on Powers and Thrones by Dan Jones.

27 December

Mark Blake has written the most accurate and complete full-length book about Queen, and so — with reservations — I picked his new Magnifico! The A to Z of Queen off the Asda shelves just before Christmas.

Inside are 132 headings, packed with overviews, facts and anecdotes. Blake has spent much of his professional life writing about Queen, so the guy knows his stuff. But the stuff in this case generally reflects a book aimed squarely at the Christmas market and not at the hardcore fan. The emphasis is very much on the sensational, the ridiculous and the outré. This is a Queen A–Z viewed through a tabloid prism.

Where, for example, more serious publications might tease the reader with vague allusions to the supposed goings-on at the legendary [sic] New Orleans party to promote the Jazz album, Blake gives it to us straight. The stories of dwarves and cocaine are just the start: “Another unsubstantiated rumour claimed an auditionee [to be an act at the party] offered to decapitate herself with a chainsaw for $100,000 — presumably she would have to have been paid up front.”

There’s good stuff to be found (I didn’t know, for example, that the vocal effect on Lazing on a Sunday Afternoon was created by a microphone fed through headphones wedged inside a tin can), but there is also no shortage of pointless trivia. Do I really need to know what Belouis Some, who opened the bill at Knebworth in 1986 — Did he? I don’t remember that! — is doing now or what his favourite Queen song is? And do we really need three pages on ‘Jesus’ aka William Jellett, apparently a regular gig-goer over the last fifty years.

It’s a filthy habit but I can’t help enjoying finding inaccuracies in ‘encyclopaedic’ books such as this. It’s a fair bet that Magnifico! is not a book Blake has taken years working on, which would explain most of the obvious errors (references to the Wembley shows in June ’86; Christmas Day 1991 being three months after Freddie’s death; Live Aid on 15 July; ‘quality over quantity’ in the Made in Heaven entry, when presumably the author means the opposite). More puzzling is a reference to You’re My Best Friend being the band’s first American top-twenty hit: clearly it wasn’t — Bohemian Rhapsody…doh — a fact confirmed by the author himself three pages later.

I have written in more detail here about books about Queen and Freddie Mercury.

30 December

More next month but I am using enforced Covid isolation over the post-Christmas week to re-watch all the Harry Potter films. I had forgotten how good they are — overly long, but good. Top marks for the casting team: the child actors were exceptionally well chosen when they were a very young age. In the first film, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, they are all convincing, despite presumably doing much of their work to blue screens and the like, and by the second film, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, they are very good indeed.

Pingback: STUDYING HISTORY HELPS US DEAL WITH CONSPIRACY THEORIES, LIES AND DISINFORMATION – Life-Based Learning