Reflections on Led Zeppelin Part 1

Friday Morning at the Funhouse with Pete Pardo and Martin Popoff on the Sea of Tranquility [sic] YouTube channel is a great watch/listen for any rock music enthusiast. Pete is the channel’s main man, and Martin is a prolific writer, critic and podcaster in his own right as well as being a frequent face on the channel. Their musical tastes are way too eclectic for me, but when I do drop by I am always struck by the astonishing breadth and depth of their musical knowledge. Whether the focus is death metal, doom metal (I can but imagine what those two subgenres sound like), hair metal, the new wave of British heavy metal, old-school heavy rock, yacht rock, pop-rock, the classic prog rock bands of the 70s, jazz fusion – I could easily keep the list going – nothing much seems to fall outside their comfort zone. It is a pleasure just to listen in, even if only for a few minutes.

I do, however, tend to stick around if the discussion relates to a genre, band or theme that interests me, and I seldom click away feeling underwhelmed by what I have heard. One episode from about six months ago, however, didn’t really cohere for me. Its title was This band’s [insert the name of a Led Zeppelin album] – in other words, they were choosing albums by bands that reminded them in some way of a Led Zeppelin album. An intriguing idea: which Iron Maiden album, for example, is their equivalent of (say) Led Zeppelin III?

But here’s the problem – equivalent in what sense? What criterion or criteria are we using? Are we talking about the overall package of songs – it’s their magnum opus, perhaps, or a significant change of direction, or the one where they over-reach? Is it to do with the production or the dominance of a particular band member? Is it the cover art? For once it was all just a bit too vague.

So Pete felt that this was what was significant about Led Zeppelin II whereas Martin focused on that; Pete thought this about Physical Graffiti, Martin that. It wasn’t too long before I was half-expecting one of them to argue that such-and-such was this band’s Houses of the Holy purely on the grounds that it was their fifth album. (Pete and Martin presumably felt the episode worked better than I did; they repeated the formula about a month later, this time with Rainbow as the non-variable.)

All of which is a meandering way of getting to my opening point – that I have been reading about and listening to a lot of Led Zeppelin recently. They were one of the very first rock bands I picked up on as a youngster, and they remain right up there in or around my top five to this day.

I wrote a blog in 2022 about some of my earliest music-related memories and album buys – we are talking the later 70s and groups like Genesis and Deep Purple as well as Led Zeppelin and, above all, Queen. (It was the companion piece to a blog about the first singles I ever bought, which I wrote a couple of years earlier.) This series of blogs is very much in the same spirit – recollections of my own Led Zeppelin journey, with some random thoughts about the band and their music thrown in.

Led Zeppelin released eight studio albums between 1969 and 1979 and were the quintessential 70s rock supergroup. This is not the story of Led Zeppelin – it isn’t chronological, for starters – but context matters so there is some band history here, based on what I have read in various books about them over the years (which I will discuss more in Part 3).

That said, if you have got this far and are still ploughing on it is fairly safe to assume that you are familiar with at least some of their music. Still, as their names will crop up a lot, I will just mention that the four band members were Jimmy Page (guitars), Robert Plant (vocals), John Paul Jones (bass and keyboards) and John Bonham (drums and percussion). Their manager, Peter Grant, also looms large – literally and figuratively – in some of what follows.

Anyway, as John Bonham might say – okay, let’s go.

A local record shop called Javelin had a phase of stocking imports of albums on the Atlantic label at a reduced price, the covers clipped along the bottom edge to identify them. It’s how I came to pick up my first Led Zeppelin records – the untitled fourth album, Houses of the Holy and Physical Graffiti. I distinctly remember the latter – which was on the band’s own Swan Song label, though distributed by Atlantic – because the centre labels were in French.

Before all that, and based on not much more than an awareness of Black Dog, Stairway to Heaven – which everyone seemed to know and admire, or at least pretended to – and the Whole Lotta Love riff that was the theme tune for Top of the Pops for a while, I recorded a Led Zeppelin live show off the radio. It was broadcast in mono on Radio 1 but also simultaneously in stereo on Radio 2, probably on the Friday Rock Show, so it was good quality. Hearing about it from a friend at school, I wrote the details on the back of my hand. A young student teacher noticed it and suggested that I was a bit young to appreciate Led Zeppelin.

He was right, of course, though as an opinionated pre-teen I certainly didn’t welcome the comment at the time. The live version of Dazed and Confused, in particular, flew way over my head, but the opening Immigrant Song followed by tracks like Heartbreaker and Black Dog packed a powerful punch, even for – especially for – a twelve-year-old. The broadcast itself was (and is) an old favourite – a BBC In Concert special as opposed to a regular gig – recorded at the Paris Theatre, London in April 1971, a few months before the fourth album was released.

The version I heard and taped was about an hour long. The cassette itself has long ago fallen to pieces but in my head I can still hear Plant saying to the audience – at the start of the acoustic set and, as I remember it, before the song Tangerine – something along the lines of ‘This is normally where we have a cup of tea, but we are going to sit down instead’.

A 70-minute version of the concert came out on the BBC Sessions CD in 1997 and then additional tracks appeared on the 2016 rerelease (called The Complete BBC Sessions). Plant’s comment doesn’t appear on either version and Tangerine isn’t even listed on set lists of the gig, so without doing any further digging I can only assume that some or all of that is a false memory.

Actually, the very first Led Zeppelin album I owned was the live soundtrack album The Song Remains the Same, bought for me by my parents when we were on holiday, probably in 1978. Not the fluffiest of introductions to the world of heavy rock, it is safe to say: a double album containing just nine tracks, four of them on side one. One song sprawls itself across the whole of side two and there is a ten-minute drum solo thrown in for good measure on side four.

The album has attracted much criticism over the years, including from the band members themselves. The original two-disc vinyl release came out in October 1976 to accompany a film of the same name. The album was heavily edited, the choice of songs for inclusion reflecting the fact that the film was meant to be at least as much “a rare series of glimpses into the visions and symbolism of the men who make the music” (to quote from the journalist Cameron Crowe’s original liner notes) as a standard concert film.

The 2007 The Song Remains the Same CD rerelease – now a complete show, though not all songs are from the same night – is a much more faithful representation of the live concert experience in that respect. Here’s the set list from the three Madison Square Garden shows that were filmed (the songs in bold appeared on the original 1976 album):

Rock and Roll / Celebration Day / Black Dog /Over the Hills and Far Away / Misty Mountain Hop / Since I’ve Been Loving You / No Quarter / The Song Remains the Same / The Rain Song / Dazed and Confused / Stairway to Heaven / Moby Dick / Heartbreaker / Whole Lotta Love / The Ocean

Crowe errs when he refers to it as Zeppelin’s most recent tour of America. Though the film and soundtrack album came out in 1976, the concerts themselves had been filmed at the end of July 1973, more than three years and two studio albums earlier. Moreover, some close-ups were actually filmed much later, at Shepperton Studios in England on a mock-up of the Madison Square Garden stage, with the band in effect miming and John Paul Jones wearing a wig.

Above all, there is also the issue of producer Jimmy Page’s apparent obsession with tinkering with the sound – cuts, edits, overdubs, cross-dubs. The incomparable Garden Tapes website – take a bow, Eddie Edwards – does an unbelievable job of showing what and where. Originally conceived as a study of the film and soundtrack album, the website was later expanded to cover the 2007 CD/DVD releases and now incorporates other official live releases too.

As a non-musician who doesn’t know his reverb from his sustain or his natural A from his B flat, I bow down to Edwards’s expertise and extraordinary attention to detail, though even this novice was able to spot the jarring cut to Whole Lotta Love just under two minutes in (where one minute and fourteen seconds of music has been removed, the Garden Tapes website informs us).

Edwards is no fan of the 2007 reissue – he writes of his hopes that a later (2018) remaster would “consign the horrors of 2007 to the dustbin of history” – but I am just glad to hear a professionally recorded and more or less unabridged Led Zeppelin concert from 1973, when some would say they were at the peak of their powers, even if The Ocean (the encore) is placed out of sequence at the end of disc one.

Back to the original 1976 soundtrack album, I was twelve or maybe thirteen when I first heard it and was immediately hooked. This brand of rock music was an antidote not just to the lightweight drivel that dominated the singles chart but also to what I saw as the amateurishness of punk music, which some of my friends gravitated towards. The Song Remains the Same defined for me what I imagined Led Zeppelin to be: serious musicians who played serious music for serious people (ie grown-ups).

This music could be as heavy and hard-rocking as the likes of Deep Purple, Black Sabbath and AC/DC but also softer, more nuanced and considerably more eclectic in its influences too. And it was more than just the music – even the album’s packaging (the original vinyl release came with a booklet of stills from the film) impressed my young mind with its apparent sophistication.

Granted, some of the songs go on a bit – I always take a breath whenever I hear those opening bass notes from Dazed and Confused – but the versions of The Rain Song, No Quarter and Stairway to Heaven on The Song Remains the Same are magnificent, definitive perhaps in the case of the first two. Dazed and Confused excepted, these iterations are expansive without being unduly rambling. Compare them with anything from the band’s ill-fated 1977 North American tour, which reeked of excess and an utter lack of restraint.

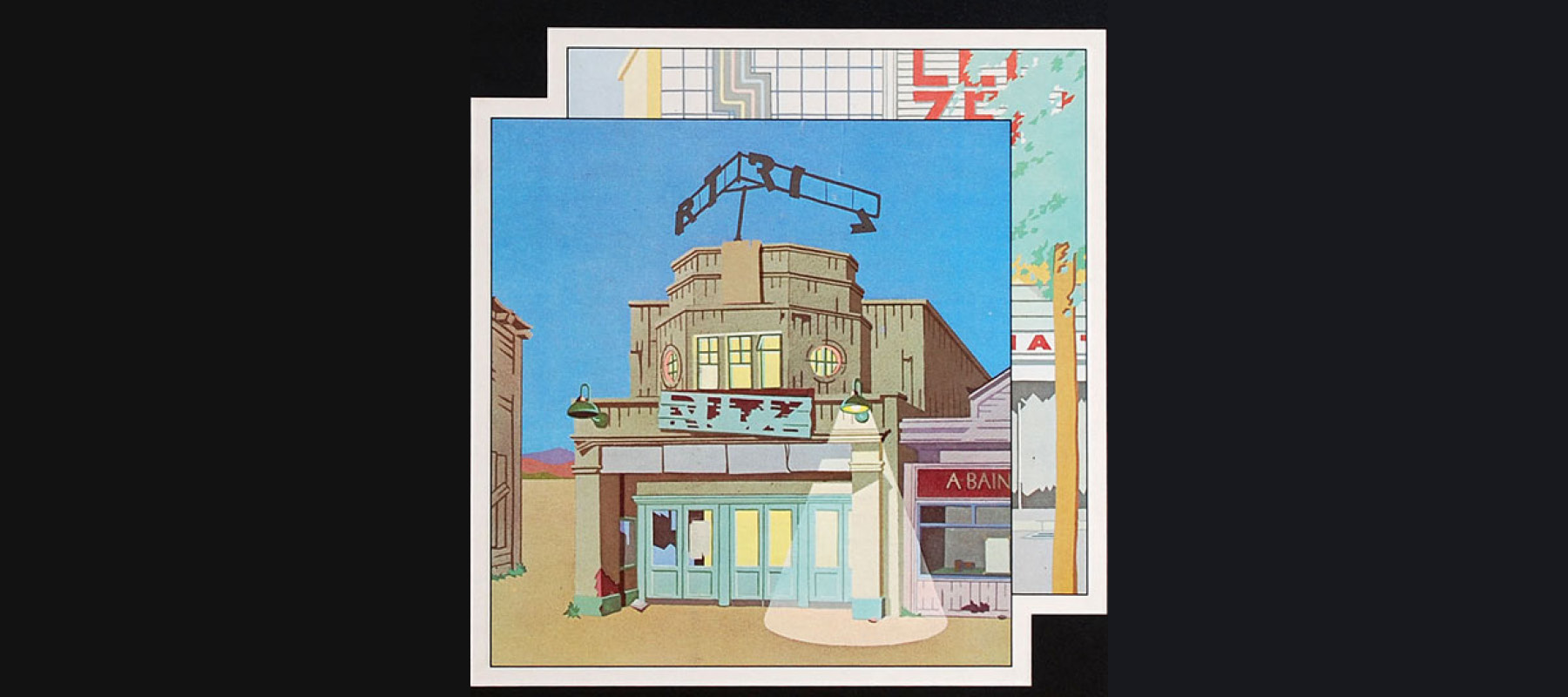

I first saw the film at a one-off late-night screening at a small cinema called – for those who know the Wigan area – Unit Four. It was a Friday or Saturday evening, probably in 1982 or 1983. When it first came out The Song Remains the Same was classified by the then British Board of Film Censors as a AA film – only for those aged fourteen and over (the 15 rating replaced the AA classification in 1982). I turned fifteen in the summer of 1981; I definitely would not have looked old enough to get in to any film underage.

Brian May’s plea to Queen fans in 1980 to watch the film Flash Gordon (music by Queen, of course) only in a cinema equipped with stereo sound still reverberated at this point, so it was a huge letdown to walk in to the cinema room and see just a single speaker set up directly underneath the screen. Whenever I hear or read the word ‘fleapit’ nowadays it is this very image that still pops into my head. That said, it was great to ‘see’ Led Zeppelin performing live for the first time, and with the inclusion of Since I’ve Been Loving You, which wasn’t on the soundtrack album, a huge bonus.

Watching it now, the five ‘fantasy’ sequences and the backstage footage are hard to sit through, though I can’t remember what I thought at the time. The special effects are on a par with a mid-70s edition of Top of the Pops, and a lengthy introductory sequence reminds us of a painful lesson we were to learn again and again during the pop-video craze of the early 80s – popstars should avoid trying to act.

The band members are plucked by Grant from the tranquil surroundings of their various – but all very English – country idylls with news of the upcoming tour. Bonham, Page, Plant and Grant at least have the sense to keep quiet for these scenes, but Jones unwisely takes on a speaking role. His wooden delivery of the “Tour dates! This is tomorrow!” line at least has comedy value, but his performance of Fee-fi-fo-fum from the Jack and the Beanstalk fairy tale should have been relegated to the cutting-room floor.

The inclusion of a fantasy sequence for the manager indicates his importance in the Led Zeppelin universe; he is the unofficial fifth member of the band. The premise – a gangster mercilessly rubbing out a rival gang in a St Valentine’s Day Massacre-style execution – reveals something of Grant’s management philosophy. Just as he was in the front line during every negotiation (sometimes almost literally – to take just one example, the writer Mick Wall describes how Grant faced down a venue manager in Memphis who pulled a gun on him, demanding that Zeppelin end their performance early), so here too he is the advance guard, first on the scene before the band makes its appearance.

The fantasy sequences for Jones, Plant, Page and Bonham – embedded within No Quarter, The Rain Song, Dazed and Confused, and Moby Dick respectively – ooze self-indulgence. Page’s scene is the interesting one, obviously inspired by his lifelong interest in the occult.

He clambers up a rocky escarpment, a full moon lighting the way, to be met by the hooded hermit – perhaps a magus (a learned magician, a key figure in occult lore) – from the cover of the fourth album who, to quote Mick Wall, “morphs through time”, revealing himself to be Page. Above all, it is the location where the sequence was filmed that is significant: Boleskine House on the shores of Loch Ness, once the home of occultist Aleister Crowley and which Page himself owned for more than twenty years.

The film, then, has more than its fair share of flaws. As for the overall concert experience, the stage set-up and lighting appear rather basic – there was a significant upgrade to both by the next tour in 1975, including the use of laser beams – and some commentators say that the performances are a bit flat. These were, after all, the final three shows of yet another drink- and drug-fuelled rollercoaster of a North American tour. Stephen Davis has written that Page hadn’t slept for a fortnight and that when he arrived back in England – “exhausted, malnourished, sleepless, raving” – his family tried to get him into a sanatorium for a rest.

But – from Bonham’s opening “Okay, let’s go!” to Plant’s closing “New York – goodnight!” – there is just no denying the power, intensity and sheer brilliance of the music.