Sebastian Faulks

Posted on October 31, 2022 by Diogenes

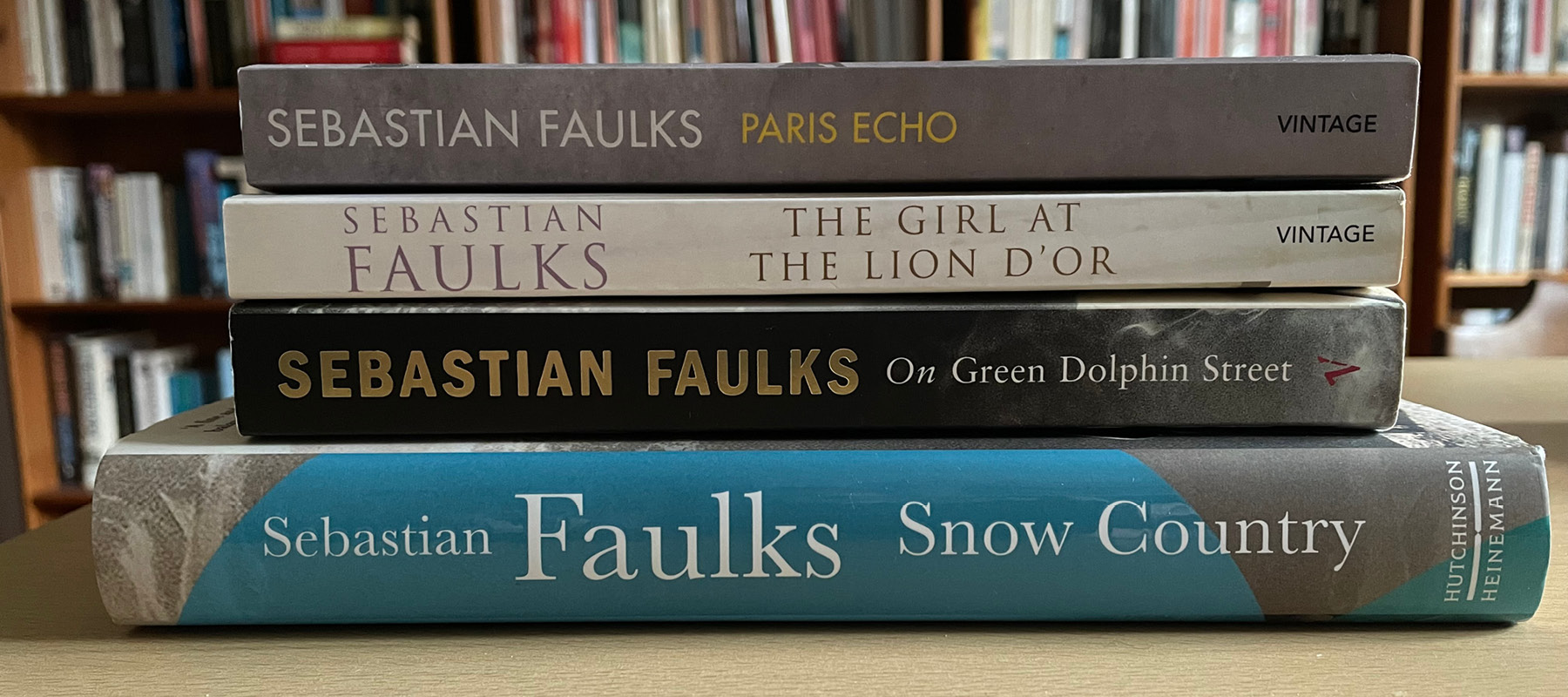

Sebastian Faulks is one of my favourite writers of fiction. This blog brings together a few thoughts on a selection of his novels that I have read in the last two years or so. Some of what follows first appeared in a books, TV and films blog I wrote between 2020 and 2022.

Birdsong is probably the novel for which Sebastian Faulks is best known, but the one I usually mention whenever I am asked about my favourite work of fiction – and not just my favourite Faulks novel – is Human Traces, which came out in 2005.

It is a colossal book – in ambition as much as in size – charting the development of psychiatric medicine and psychoanalysis in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. It tells the story of two pioneers in the field of psychiatry, one English and one French, who open a sanatorium, the Schloss Seeblick, in Austria. A brilliant mix of imaginative reconstruction, historical exposition and invention, Human Traces is intense, dense and challenging, perfectly capturing the intellectual temper of the times.

Published in 2021, Snow Country is, in Faulks’ own words, a sequel of sorts. It returns us to the Schloss Seeblick, which acts as a focal point, bringing together the novel’s two main protagonists.

Faulks is a master at interweaving epoch-defining events into the lives of individuals. Here the backdrop is both the Great War itself and more specifically the damage it wrought. Though the novel spans 20 years, much of it is set in the thirties, a time of huge uncertainty across Europe. The economic depression has eroded the hopes and optimism of the later-twenties. Authoritarianism and fascism are everywhere on the rise; democracy, by contrast, is everywhere in retreat, not least in Austria itself where ‘Red Vienna’ is at loggerheads with the Catholic hinterland. It is in these unpropitious circumstances that Anton and Lena – and others – try to find a sense of meaning in their lives.

Faulks’ ability to conjure up a sense of time and place – be it the trenches of the Western Front, Occupied France during the Second World War, present-day London – is also on show in On Green Dolphin Street (published in 2001), which takes place in New York at the end of the fifties and beginning of the sixties. As always with Faulks, the background research is thorough and the attention to detail remarkable.

It’s a whirlwind tour of delis and diners, apartment blocks and shops, bars and nightclubs, all to a backdrop of jazz (On Green Dolphin Street is apparently a Miles Davis classic). The busy, bustling, labyrinthine streets of New York are wonderfully drawn. Faulks is perhaps using the city as a metaphor – its bewildering complexity and its dazzling possibilities. The Second World War is also a lingering presence, casting its long shadow years after the war itself is formally at an end.

Faulks is also a wonderful crafter of stories, adding layer upon layer as he goes and weaving threads of context and background that combine to form a convincing picture of the characters and their lives. On Green Dolphin Street is much more than just a conventional love story. It explores the different types of loving relationships – the unconditional love between parent and child; that life-changing first love; the love that grows and develops between lifelong partners; passionate and erotically charged love; and love between two soul mates.

After briefly worrying that the ending was turning into a rerun of the final episode of the US TV comedy Friends, I found the conclusion satisfactorily unsatisfactory. It was, after all, an impossible dilemma that Mary faced.

The Girl at the Lion d’Or is one of three Faulks novels (not counting Paris Echo) set in France in the first half of the twentieth century – this one taking place in the thirties, the final decade of the Third Republic. Just like On Green Dolphin Street, the novel is beautifully crafted: it’s a love story, but so much more as well. Every character, every event (however seemingly incidental), every exchange, every detail helps paint a picture of France in the years leading up to its collapse and national humiliation in May and June 1940.

The terrible impact of the 1914–18 war, particularly the psychological scarring left on the wartime generation, looms large. People are politically rudderless, losing faith in democracy and receptive to extremist solutions; the Jews are convenient scapegoats for the nation’s ills. Hartmann’s old family home serves as a metaphor for the Third Republic itself, the cracks in its structure gradually growing larger and its foundations undermined by the troubled builders’ shoddy workmanship.

We are also back in Faulks’ beloved France for Paris Echo (2018). The two central characters are Hannah, an American historian researching women’s experiences in Paris during the Occupation, and Tariq, an undocumented Moroccan immigrant, whose family history has been shaped by France’s colonial past. Both arrive in Paris looking for something, though neither is clear quite what that ‘something’ is.

Paris Echo has all the familiar Faulks trademarks, not least an incredible sense of place. If I had to sum up in one word what I love about Faulks’s writing, it would probably be the ‘interweaving’ referred to above. It is there in all his books but is absolutely central to this one – the ‘echoes’ of the title. One story weaves in and out of another; characters intermingle, one with another; the past intersects with the present; locations intersect with stories. It is all wonderfully, wonderfully crafted. Overarching it all is a deep love of, and respect for, the past.

The novel is full of mystery. There is the fragility and contingency of Hannah’s work, as she tries to reconstruct the past. As a historian by training and someone who reads a lot of history, I was struck by the observation that people who live through ‘historic’ events might not experience them as such, especially if their most pressing day-to-day priority is simply survival.

There are many unanswered questions surrounding Tariq, too. What was the traumatic experience in his family’s recent past? What is the nature of his out-of-body ‘autoscopic’ experiences? Is Clemence real or just a drug-induced hallucination? For the reader it is frustrating – but fitting – that Faulks doesn’t give us any easy answers to these and other conundrums.

Recent Posts

- Queen I Review May 5, 2025

- Genesis Bootleg History Overview November 20, 2024

- London 1992: Genesis Bootlegs November 5, 2024

- Los Angeles 1986: Genesis Bootlegs September 17, 2024

- Reflections on Led Zeppelin Part 2 August 10, 2024

- This Time No Mistakes July 4, 2024

- Reflections on Led Zeppelin Part 1 April 11, 2024

- Reading Historical Fiction October 9, 2023

- In Praise of Gyles Brandreth August 4, 2023

- Johnson at 10 Book Review June 30, 2023