Reading Historical Fiction

I suppose that I have always enjoyed reading historical fiction, if by that term we simply mean books set in the past. Let’s face it, we’re talking about a genre that’s all but impossible for any reader of novels to avoid. I grew up on television wartime dramas like Colditz and Secret Army – and films like The Great Escape and The Dam Busters – so it’s no surprise that as a teenager I tended to alternate between, on the one hand, the write ’em quick and sell ’em even quicker novelists like Jack Higgins and Alistair MacLean and, on the other, the horror stuff that Stephen King and James Herbert were putting out.

But at that age it wasn’t the history that was drawing me in. I raced through all nine Sherlock Holmes books by Arthur Conan Doyle on a school holiday to France at the age of 14, but it was primarily the crime puzzles themselves (the dancing men, the Red Headed League etc), the elegance of the deductive reasoning method and of course the singular character of Holmes himself that snared me. If anything, place – principally (but of course not exclusively) the fog-bound streets of London – made more of an impression on my teenage mind than time.

A couple of years later, the attention to detail in Frederick Forsyth’s The Day of the Jackal (set in 1963) grabbed me, but the detail in question was the planning and preparation relating to the assassination attempt on President de Gaulle itself rather than the wider political-historical context (ie France and the Algerian War).

Skip ahead a couple of decades and The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco took me somewhere I never expected to be – a fourteenth-century Italian monastery, to be precise – but, as with Holmes, the detective work and the book’s other intellectual puzzles were its appeal. (In the novel the main protagonist, William of Baskerville, is an obvious nod to Holmes.) The author’s recreation of medieval monastic life rather passed me by, except insofar as it impinged directly on the plot.

It is only in the last few years that I have embraced the idea of fiction as a portal to the past. And that only happened when I opened my mind to the idea that the past – or at least the past as a subject of interest – doesn’t begin in or around 1900. Try my blog about Steven Pinker’s marvellous book Enlightenment Now for more about that ridiculously belated journey of discovery.

Reading Kate Mosse and then Hilary Mantel (I think in that order) was a revelation. I discovered that historical fiction – the well-written variety at least – can be a friend to the uninitiated, an entrée into worlds only dimly understood or appreciated – in this case medieval France and Tudor England respectively. I remember taking a chance on Kate Mosse’s 2005 novel Labyrinth and – perhaps thirty or so pages in – a voice shouting at me from off the page: This is fabulous. Why have you never taken an interest before, you idiot?!

The two disciplines – history writing and historical fiction – are not of course the same and, as I have written before, the distinction between the two should not be blurred. Though still requiring encyclopaedic knowledge and command of the sources, the writer of historical fiction takes a different approach to that of the historian or biographer and requires a different skill set.

There is, for example, no room for ‘possibly’, ‘probably’, ‘maybe’, ‘on balance’. It is, in part at least, history of the imagination, the author using a time and a place, an individual or an event as the starting-point for a story, deploying their knowledge and skills to interweave fact and fiction in order to create something plausible and convincing.

The writer of good historical fiction must also be something of a tightrope-walker, ensuring that the reader is given sufficient contextual detail without either sounding didactic or overloading the text with extraneous detail. I have written here about how Dennis Wheatley – admittedly not the first name that springs to mind when compiling a list of writers of historical fiction – did himself no favours when he filled one of his horror novels with page after page of wooden and unconvincing dialogue about Aleister Crowley.

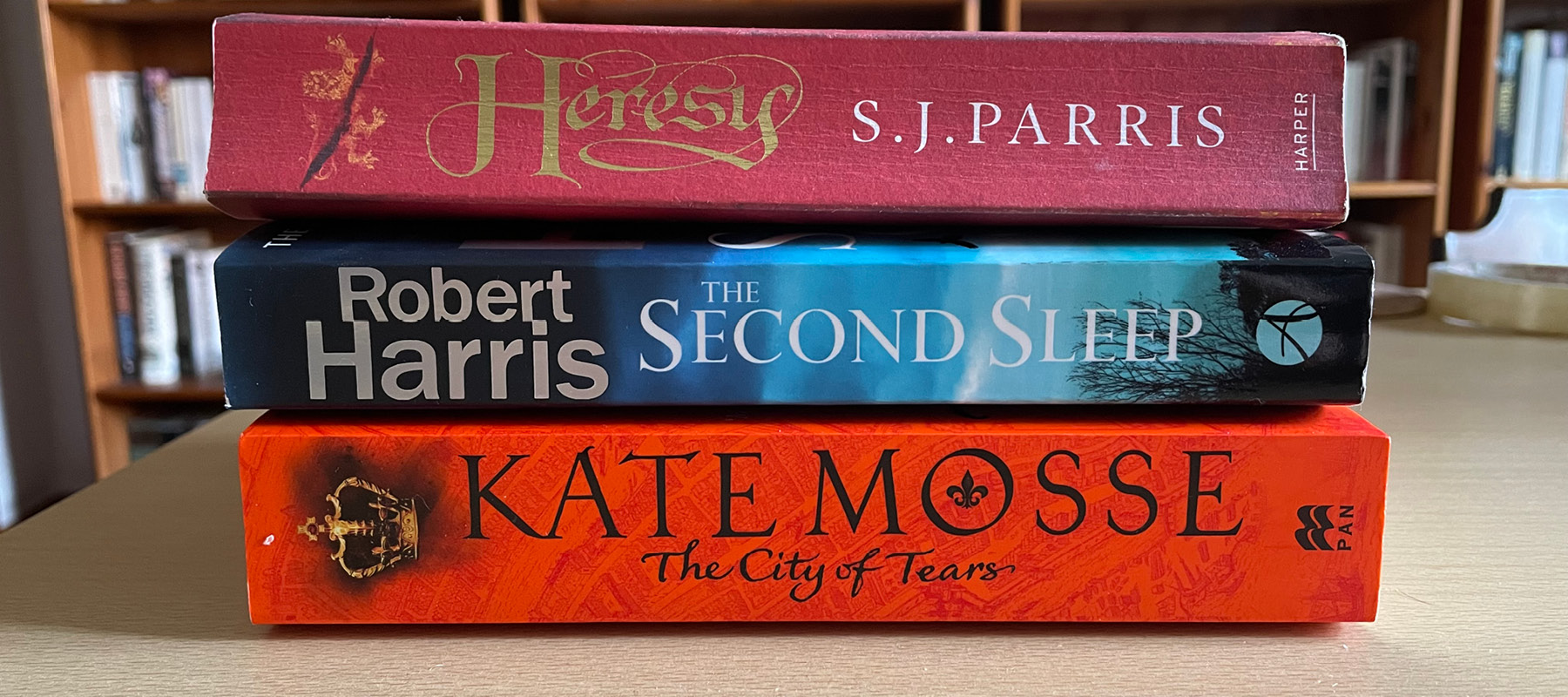

Compare that with (say) Kate Mosse’s 2020 novel The City of Tears. The city in question is sixteenth-century Amsterdam, home to refugees from far and wide, though much of the story actually hinges on events in Paris in August 1572 – the so-called St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. Arcane religious and political divisions play a central role in proceedings, but the writer guides us expertly through and at no point does the reader feel overwhelmed by complicated or unnecessary detail.

That is why I found the 2020 novel V2 by Robert Harris a little surprising. In many respects it is classic Harris, sculpting a gripping story out of real historical events, in this case the Germans’ Second World War V2 rocket programme and British efforts to foil it. But at several points Harris chooses to take off the mask of the novelist and reveal himself as a historian. Here’s an example, describing a V2 that hit a department store in Deptford, killing 160 people. I have underlined the bits that raised an eyebrow:

One young mother, with a two-month-old baby in her left arm, walking up New Cross Road on her way to the fabled saucepan bonanza, recalled forty years later “a sudden airless quiet, which seemed to stop one’s breath.”

Robert Harris, V2, page 38

Here’s another – the context in this case that several V2s were fired on the same day:

What happened to the third missile remains a mystery. It took off perfectly at 10.26am, but there is no record of its impact anywhere on the British mainland. Presumably it must have exploded in mid-air, perhaps during re-entry.

Robert Harris, V2, page 76

It works the other way too. There is a growing tendency, as far as I can tell from my relatively limited reading, for ‘popular’ history (ie books about history that are written for the intelligent general reader rather than for an academic audience) to stray worryingly close to historical-fiction territory.

This, for example, is the opening sentence of Powers and Thrones by Dan Jones, a book about the Middle Ages: “They left the safety of the road and tramped out into the wilderness, lugging the heavy wooden chest between them.” There is a footnote six lines later, but it merely informs us of how much the chest would have weighed. And then a couple of pages later: “They had walked far enough that the nearest town – Scole – was more than two miles away; satisfied that they had found a good spot, they set the box down.”

The chest that Jones describes contained what is now called the Hoxne Hoard, discovered by metal detectorists in 1992 and displayed in the British Museum. The notes refer to a 2010 book on the Hoxne Hoard by Catherine Johns. But how much of this detail does Jones actually have supporting evidence for – how, for example, does he know that they were satisfied they had found a good spot? – and how much of it is just creative scene-setting, the product of educated guesswork and the writer’s imagination?

As it happens, Dan Jones is one of a number of historians who also write historical fiction. His debut novel Essex Dogs is on my shelf, waiting to be read at some point in the next few weeks. A puff quote tells me to expect “the Hundred Years’ War as directed by Oliver Stone”. That sounds fun. To pick another random example, Simon Sebag Montefiore’s 2013 novel One Night in Winter, set among the Soviet elite during the last years of Stalin’s rule, is terrific. And then there is Ian Mortimer, perhaps best known for the A Time Traveller’s Guide to… books. He writes historical fiction under the pen name James Forrester.

But back to Robert Harris for a moment, I have been a fan ever since I read his debut novel Fatherland. Although all his books are rooted in history and/or politics, he ranges from ‘alternate reality’ settings (Fatherland being a good example: the reader quickly learns that Germany won the Second World War) to novels that stick fairly close to actual events, such as An Officer and a Spy, Munich and Act of Oblivion. When someone on X (formerly Twitter) asked what kind of stuff Harris writes, it took me a while to think of what to reply. I eventually answered: ‘Mainly well-plotted thrillers, often tied in with real historical events. Superbly researched.’

To repeat the point made earlier, thorough research is a sine qua non of good historical fiction. Harris never disappoints. The novel V2 contains all the ingredients I associate with his writing, principally a cleverly structured novel that keeps us turning the page (even though, like An Officer and a Spy and also Munich, we already know the outcome) and helps to contextualise and humanise the cast of believable, three-dimensional characters. Thus, the use of flashbacks to fill out the life story of the German scientist Rudi Graf and his longtime friend Wernher von Braun doubles as a history lesson in the German rocket programme.

I have always been interested in stories that involve time travel – which I guess is a subgenre of historical fiction – or to be more precise, perhaps, playing around with history. I always cite Making History by Stephen Fry as one of my favourite novels: imagine if you had the chance to ensure Hitler was never born. As a child I was mesmerised by the film version of The Time Machine, though I was quickly put off reading the original HG Wells book at that age by the very first sentence: “The Time Traveller (for so it will be convenient to speak of him) was expounding a recondite matter to us.” That was too much for a (probably) just-about-teenager who had the latest Whizzer and Chips as an alternative read. Ben Elton’s Time and Time Again is another novel that – as the title suggests – mucks about with history.

I think I have read everything by Ben Elton, ever since his first novel Stark had me laughing out loud thirty or so years ago. For a long time he specialised in satirising whatever was the latest pop-culture obsession – drugs, talent shows, Big Brother-style fly-on-the-wall TV. I enjoyed some of his books more than others. Blast from the Past was great (page one – “…when the phone rings at 2.15 in the morning it’s unlikely to be heralding something pleasant”), Inconceivable less so. Some of his later efforts have been more serious stabs at historical fiction – The First Casualty (the First World War) and Two Brothers (Nazi Germany).

The predictability of the characters in Time and Time Again grate a little, I must admit. They are all larger-than-life versions of Elton himself in a way. Hugh ‘Guts’ Stanton is the biggest, baddest ‘survivalist’ soldier around. Bernadette Burdette is the beautiful, loquacious free spirit he meets on a central European train, her every thought and utterance typical of the 2010s rather than the 1910s.

Least believable of all is the foul-mouthed distinguished professor of history at Cambridge University who seems to think like a Sun editorial. Okay as a one-off maybe, but then we meet the Lucian Professor of Mathematics, an “appalling media tart” who wears a ‘Science Rocks’ badge and says things like “Why in the blinking blazes was old Isaac getting his knickers in a twist?” Old Isaac being Sir Isaac Newton.

Nevertheless, one thing that Elton does brilliantly is plot. He is astonishingly imaginative, and although the basic set-up here is familiar – travelling back in time to change the past and therefore the future – Elton packs it with plenty of twists and turns. One, in particular, had me gasping (on page 441 of the paperback). Nicely done, sir. I also liked the fact that the infamous assassination in Sarajevo happens (or rather, doesn’t happen) halfway through the book, allowing Elton to have plenty of fun with counterfactual histories.

I have already said that Fatherland was Robert Harris’s first go at ‘alternate reality’ writing. The Second Sleep is also an intriguing stab at what-iffery. It ranges across several of my favourite fictional genres – it’s a mystery and a thriller as well as a history-twister (is that a genre name?). It is brilliantly structured and genuinely gripping; we’re talking Robert Harris, after all. Nothing is quite as it seems. I also found it to be refreshingly thought-provoking. Without wanting to give the plot away, others have commented that it is an urgently needed ‘wake-up call’. It is certainly hard to miss the many references to plastic.

I have written here about my fondness for the novels of Sebastian Faulks, most of which are set in the past, and It would be remiss of me to finish without mentioning two writers – neither of whom is named Hilary Mantel – who have been exceptionally helpful as I desperately try to learn more about Britain at the time of the Tudors and Stuarts.

The first is SJ Parris. Sacrilege, set in England in the time of Elizabeth I, was the first novel of hers I read, and I quickly realised that I had landed in the middle of a series about a free-thinking and adventurous Italian philosopher called Giordano Bruno. (By the way, I keep mixing up SJ Parris and CJ Sansom: similar names, similar covers, similar titles.) As usual, I wanted to start at the beginning of the series and not in the middle, which took me to Heresy, first published in 2010.

The prologue (the origin story of sorts) is actually set not in England but in Naples at the Monastery of San Domenico Maggiore. We meet Bruno in the privy, caught not quite with his pants down reading a copy of Erasmus’s Commentaries, which was on the Catholic Church’s Index of Forbidden Books. He escapes just ahead of the arrival of the Father Inquisitor, whose verdict would not have been in any doubt. Seven years later, and now in England, Bruno is taken on by Sir Francis Walsingham as one of his vast network of spies working on behalf of the Elizabethan state.

Heresy has everything you would want and expect from great thriller writing: mystery, deceit, treachery. In short, the twists and turns are suitably tortuous, the pace utterly relentless and the thrills page-turningly thrilling. I read the second half of the book in a single day.

The backdrop is, as the title suggests, the internecine religious struggles of the time, when arguments about faith, sometimes over what to the modern mind might seem minor doctrinal differences, could result in appalling bloodshed (bringing us neatly back to events in Paris in late August 1572 – the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre – which I mentioned earlier). As an aside, I was struck by the thought that SJ Parris’s description of a secret Catholic mass at the dead of night could just as easily have come from the pages of a Dennis Wheatley black magic novel:

I found myself in a small room crowded with hooded figures who stood expectantly, heads bowed, all facing towards a makeshift altar at one end, where three wax candles burned cleanly in tall wrought silver holders before a dark wooden crucifix bearing a silver figure of Christ crucified.

from Heresy by SJ Parris

The second is Andrew Taylor. The Last Protector is perfectly readable as a standalone novel but is also apparently the fourth in the Marwood and Lovett series set in the London of the mid-1660s, a time of plague, the Great Fire and (in this novel set in 1668) plots against the Crown.

Taylor is an excellent guide to the England of Charles II, with impressive knowledge of Restoration London. He brings out superbly the etiquette, codes and manners, the rigid social hierarchies and the contradictions of the age – particularly the fabulous wealth juxtaposed with gut-wrenching poverty, and the public displays of morality, decency and civility so often masking disreputable and hypocritical private behaviour.

All in all, thoroughly enjoyable. There is plenty more SJ Parris and Andrew Taylor for me to work through (not to mention the weighty CJ Sansom books). There is also The Ghost Ship, the new novel by Kate Mosse. And don’t even think to mention Ken Follett…

And then there are all those ‘cosy crime’ novels I enjoy…

No wonder one of the first blogs I wrote was called The bibliophile’s curse.

Some of this content first appeared in a books, TV and films blog I wrote between 2020 and 2022.

Your posts always feel like a conversation between friends. Thank you for making your readers feel seen and heard!

Just rereading Stephen Kings 11.22.63 which is in the time travelling to the past to change the future genre and enjoying it more than I did first time round pal.

Yeah, a fabulous read – and a great example of the genre! Thanks for posting, pal!