Books About Freddie Mercury and Queen

Reviewing a biography of Queen by Laura Jackson on Amazon back in 2002, I bemoaned “the frustrations of the literate Queen fan”. It was a (very) clumsy — not to mention pompous — way of saying that here was yet another 300 or so pages of drivel in the ‘popular’ biography genre (ie books about celebrities written for the mass market).

“What is so desperately needed [I went on to say] is a Johnny Rogan of the Queen world to give us a sympathetic yet objective account; yes, to unearth the obscure but also to offer us much more. Someone to detail the downs as comprehensively as the ups, the mistakes as well as the triumphs. Someone to probe, to question, to challenge.” I have never been a big reader of books about music (precisely because of the non-existent quality threshold), but Johnny Rogan’s biography of the Smiths, Morrissey & Marr: The Severed Alliance, was at that moment in time by far the best I had come across, combining thorough research with great writing.

Things have moved on in the last couple of decades, though I still generally steer clear of music-related books. There is decent and often good writing to be found in music magazines, not to mention several websites catering for obsessives interested in arcana, minutiae and all things encyclopaedic. My go-to website is queenlive.ca

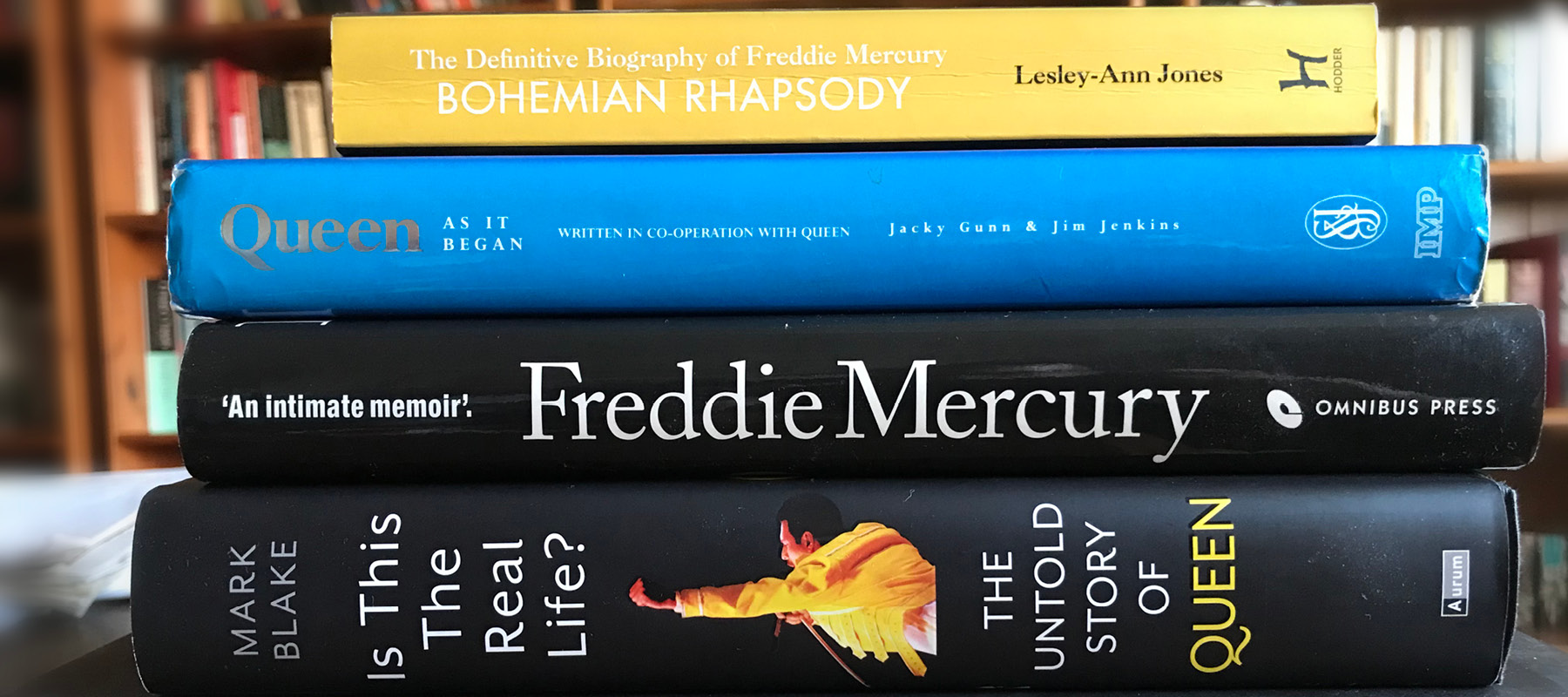

There are also some good Queen books out there now as well. The first to appear was As It Began in 1992, written by Jim Jenkins and Jacky Gunn. An important caveat is that the authors are both lifelong fans (Jacky is a longtime runner of the fan club) and neither of them is (to my knowledge) a writer. Nevertheless, As It Began was the first detailed, book-length history of the band and in that sense plugged a significant information gap. (There were two earlier paperbacks – one by George Tremlett and one by Larry Pryce, both published in 1976, I think – but they were obviously works-in-progress.)

Another notable book, by Peter Freestone, came out in 1998. ‘Phoebe’ was Freddie’s personal assistant for the last twelve or so years of the singer’s life. Although the publisher’s blurb did not augur well — “the most intimate account of Mercury’s life ever written … Now [Freestone] tells all” — it was actually a very enlightening and enjoyable insight into Freddie’s life, a book for genuine fans who wanted to know more about their hero but not in an obsessive or prurient way. I wrote at the time: “For anyone curious to know about Freddie’s lifestyle, this book surpasses anything else I’ve seen.”

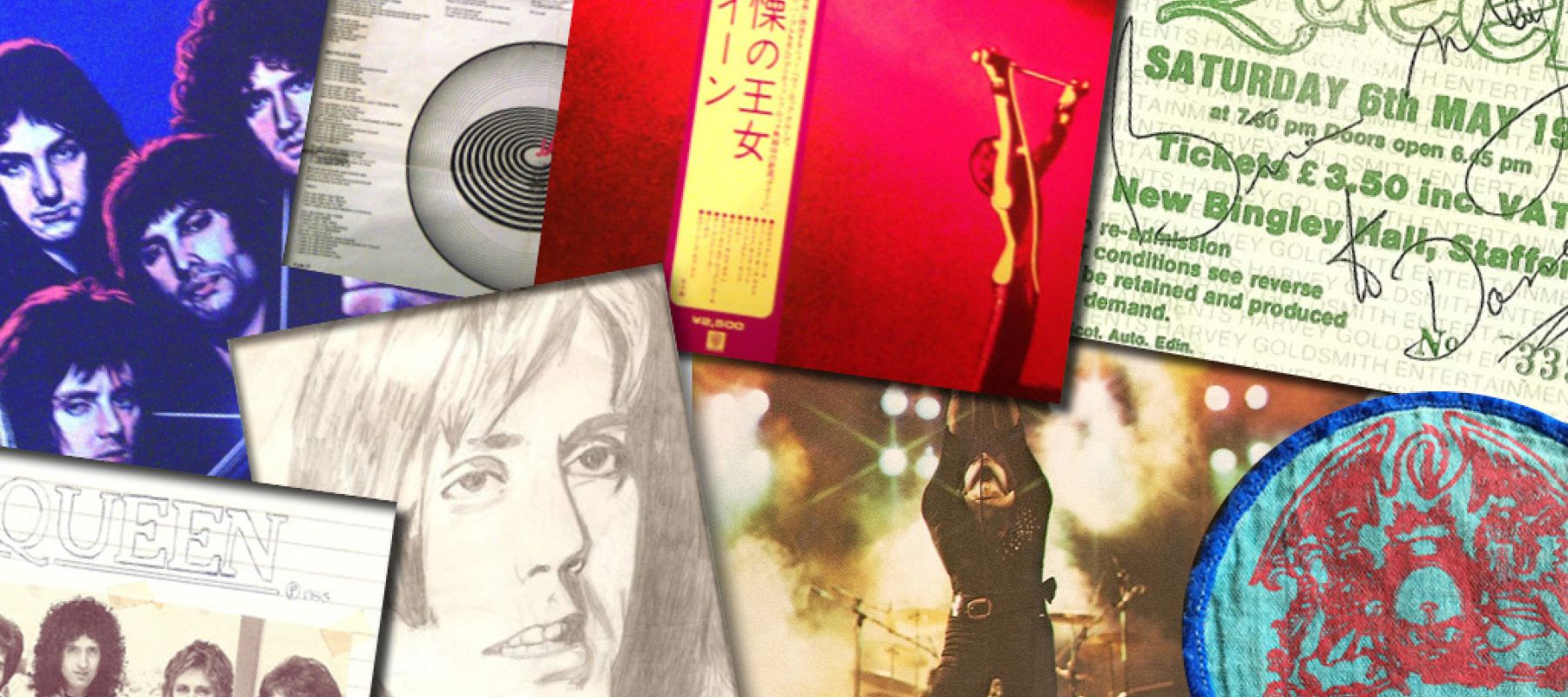

There are two very good ‘coffee table’ books, both now much cheaper than when first published (and perhaps available under different titles). One is the official 40 Years of Queen (2011). The other is Queen: The Ultimate Illustrated History of the Crown Kings of Rock by Phil Sutcliffe. Both books are sumptuously presented, full of great photos and packed with memorabilia (the official book, literally so). I should also mention Brian May’s Queen in 3–D which is a must-have for a Queen fan, one that literally presents Queen in a new way. Meanwhile, the nearest thing to a Johnny Rogan-type book is Mark Blake’s detailed and, for the most part, decently written Is This the Real Life: The Untold Story of Queen?

And so we come to Bohemian Rhapsody: The Definitive Biography of Freddie Mercury by Lesley-Ann Jones, a book I resisted buying when it was released and only picked up from a charity shop a few weeks ago. Originally published in 2011, it was reissued in 2018 with a new title, no doubt to cash in on the release of the Bohemian Rhapsody biopic. I am not aware of an official tie-in but snippets of the film script mirror the book’s contents (most obviously Freddie’s ‘coming out’ conversation with his girlfriend Mary Austin — though I strongly suspect the supposed dialogue between Freddie and Mary was already in the public domain when this book was published).

It is not uncommon for books (and films) to begin with a scene-setting introduction, usually a pivotal moment in the story arc — something to whet the appetite, to build towards. Mark Blake chose Live Aid for his Queen biography (as, of course, the Bohemian Rhapsody film did too); he later chose Live 8 for his excellent Pink Floyd biography, the performance at Hyde Park when those best of enemies, Dave Gilmour and Roger Waters, put aside decades of ill-will for twenty minutes to help out starving people.

Lesley-Ann Jones has not one but two such chapters: an introduction entitled Montreux and Live Aid as chapter one. It is chapter two — Zanzibar — that whisks us back to Freddie’s childhood. The introduction is written in the first person. Fair enough for an introductory chapter, perhaps, but this Jones-centred perspective foreshadows one of the most irritating features of the book: the author’s frankly intrusive presence. Jones evidently wants the reader to be aware of two things: (i) that she has done plenty of background research (ii) that she had some privileged access to the band back in the day. The inclusion of photos of the author with some of her interviewees handily reinforces these twin messages.

The very first sentence of the introduction is: “We didn’t write it at the time.” Her point is that music journalists (of whom she is one) did not take notes or use tape recordings in many of their interviews; instead, they relied on memory, frantically scribbling things down at the first available opportunity. In chapter one our location is a quiet bar in Montreux in the early hours of a spring day in 1986, just before Queen embarked on their biggest ever European tour. She and a fellow hack had found themselves in conversation with Freddie who — for whatever reason — was opening up to them. On page 5 there is a paragraph — in quotation marks — of more than 100 words. There are several such paragraphs — Freddie’s words, seemingly verbatim. Quite a feat: either Jones has a prodigious memory or quotes such as these are not quite what they seem. Or perhaps it comes with the territory: the pages of Obama’s memoirs, just published, for example, are peppered with snatches of conversation.

The list of interviewees is long and includes several people who played a notable part in Freddie’s life — Peter Freestone, Jim Hutton and so on. There’s also Spike Edney to talk about the final two tours. On the other hand, it is hard to see what unique insights session musician James Nisbet, who never to my knowledge worked with Queen, brings to the table. As far as I can tell, Jones has not interviewed any of the surviving members of the band for the book; nor does she appear to have had special access to either Mary Austin or Jim Beach, Queen’s longtime manager and one of the executors of Freddie’s will.

Many of the quotes the author uses seem to be recycled from previous research that she has done or taken from other publications and programmes. Much of the Live Aid chapter, for example, is built around previously available material. With quotes featuring so prominently throughout the book, the lack of quality control is a weakness. In offering us his thoughts on Freddie’s lyrics, Frank Allen, bassist with the Searchers, refers to two songs that Freddie didn’t even write.

Lexico defines ‘definitive’ as “the most authoritative of its kind” and ‘authoritative’ as “considered to be the best of its kind and unlikely to be improved upon”. Despite the recommendation of Sir Tim Rice in one of the puff-quotes, Bohemian Rhapsody: The Definitive Biography of Freddie Mercury is neither definitive nor authoritative. To be fair to Jones, it is not riddled with the sort of factual howlers common to other books about Queen. But even if we interpret ‘definitive’ in a looser sense to mean ‘covering all relevant areas in appropriate depth’, it is not that either.

In an attempt to appear definitive the writer offers a mass of redundant detail. There is a paragraph about the history of the unrest in Tanzania and Zanzibar in 1963–4 that led the Bulsara family to relocate to London. We learn about Zoroastrian rituals, even though Freddie never seems to have adhered to them. These parts of the book feel like quick cut-and-paste jobs from Wikipedia. Other research lowlights include reproduction of a band press release about the Magic Tour (x miles of cable etc); a paragraph of completely irrelevant detail about Elton John’s marriage, and the name and date of birth of his son; even a couple of paragraphs on the semiotics of clothing in gay nightclub culture.

This is a shame because at times Jones puts her journalistic skills to good use, uncovering some minor but nevertheless intriguing facts about Freddie’s early life. Tracking down Freddie’s first ‘girlfriend’ gives us a fresh perspective on his teenage years, and the best nugget of all is that, if Jones is correct, Freddie lied about his O-level results. [I now realise that Mark Blake’s book, published a year earlier, makes the same claim. — Diogenes]

The book as a whole is unbalanced and suffers from some glaring omissions. Much of its first half might be described as ‘emergence of a rock star’, but there is little of value here for the reader interested in the music itself. Take, for example, two significant early Freddie songs from Queen II. The lyrics of The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke are based on a detailed and intricate painting by troubled nineteenth-century artist Richard Dadd. They are obviously the result of painstaking research, certainly not something one would associate with later-era Freddie. The March of the Black Queen, meanwhile, over-reaches and almost keels over under the weight of its grandiosity; yet it is utterly audacious and quite magnificent. It is impossible to listen to Bohemian Rhapsody and not hear echoes of Black Queen.

From Jones there is not a word about either song. The narrative focus at this point is on describing Queen’s commercial breakthrough. And then — once we reach 1975–6 and the extraordinary success of Bohemian Rhapsody — it shifts largely to price-of-fame stuff, specifically its destructive effects. This is, of course, a biography of Freddie Mercury and not a book about Queen and their music, but Jones’ approach means that interesting and relevant questions about Freddie go all but unexplored:

- What kinds of songs did Freddie write and what were the main themes in his lyrics?

- How and why did his songs change over the years?

- What was the nature of his creative input into the band in later years?

- How did his friendship with each member of the band evolve over time?

A more imaginative approach to structure might have involved organising the book into different parts or themes. Separate sections dealing (a) with Freddie’s personal life and (b) with Queen and their music would have ensured that the one wasn’t completely elbowed out by the other. It would also have helped keep details of Freddie’s personal life within reasonable limits and helped the writer to focus more on how it developed over the years.

Alas, details about Freddie’s relationships move to centre stage, increasingly consisting of interview quotes reproduced at length. By the time the narrative reaches the 1980s, discussion of Queen’s music is relegated to a handful of anodyne sentences indistinguishable from the content of the fan club magazines of the time — except for the occasional somewhat bizarre throwaway, such as Roger’s second solo album being “widely ridiculed”. References to the rest of the band’s personal lives, on the other hand, are typical of tabloid newspaper fare:

Brian had already managed to fall in love with a girl called Peaches down in New Orleans. John, generally mindful of his domestic commitments, had taken up with the bottle. Roger was always the life and soul of anyone’s party, rarely knowingly alone between midnight and breakfast.

Bohemian Rhapsody, page 182

This is not the only weakness of the writing. Any biography is prone to succumbing to a form of teleology — the sense that the subject’s rise was somehow inevitable, events all part of a long-term plan mapped out at the very beginning. Most people who reach the top are clearly driven; it is one of the reasons why they get there. Equally, however, we all have grandiose aspirations and ambitions in our youth. It is an easy mistake to make to confuse the one with the other.

An example of this comes in chapter one when Jones asserts that Live Aid was Queen’s “ultimate moment, towards which they had been building their entire career”. This ridiculous assertion might usefully be described as ‘hindsightery’ — explaining the motivations behind decisions in terms of what later transpired.

Brian and Roger were in a group called Smile; Freddie, though already a friend, was in various bands of his own, one of which was called Wreckage. In chapter six we are told: “He soon quit the band [Wreckage], resolved to wait for Brian’s and Roger’s pennies to drop, and auditioned for a band called Sour Milk Sea.” It surely isn’t just the writing that is dodgy in that sentence. What actual evidence does Jones have that Freddie was patiently waiting for Smile to implode so that he could step in?

Some of the writing just reads like Sunday-supplement copy. Smile were on the bill for an event at the Royal Albert Hall, as were the band Free: “… little could Brian and Roger have known that, thirty-five years later, they would be collaborating with Free’s lead singer Paul Rodgers.” No, I don’t imagine they could have known. Or this: “Freddie was not yet ready for anything like marriage. Little did his family know at that stage that he never would be.”

There’s more. A poorly edited version of Liar from the first album was released in North America by their record company (ie without the band’s input): “It had now dawned on the band that, only by retaining close to complete control over their work could they relax enough to take risks with their creativity. This was to set the template for Queen’s entire career.”

Equally dubious is the practice of describing how the writer imagines someone would feel. Take this, about Freddie’s birth: “When the news reached her husband at work, Bomi rejoiced. The family name would continue.” Regarding the decision to send Freddie thousands of kilometres away to boarding school in India: “Jer and Bomi must have felt that they were doing the right thing at the time.”

There is an awful lot of speculation and guesswork masquerading as psychology — attempts to ‘uncover the real X’, another celebrity biography trope. Jones uses several epigraphs (quotes at the beginning of each chapter) from a “consultant psychiatrist”. Most of the time, though, it’s amateur-hour stuff: “Perhaps what he felt in his heart was …”. Friends and colleagues offer their wisdom too. Here’s Jim Hutton: “All the petting and stroking which he lavished on the cats, for example: it was what he wanted for himself.”

Worst of all is the chapter on Mary Austin, complete with comments from “music publisher Bernard Doherty”. The depths are properly plumbed when he witters on about the “Mother Mary” lyric in Let It Be by the Beatles — “coincidentally”, we are told, released in 1970, the year that Freddie met Mary. “Mary was the Mary in that song. She was pure.” To his comment that by the end they weren’t having sex, Jones asks rhetorically: “Because by this time Freddie had chosen to be gay, rendering Mary a born-again virgin?” Then there is an attempt to describe Mary’s feelings for Freddie as “Mother Love”, ending with: “No surprise that this would eventually become the title of a plaintive track sung by Freddie and Brian …”. Yuk.

The attempts to interpret Freddie’s lyrics are awful — it is a subject that Freddie himself hated discussing. A page of utter tosh about the lyrics of Seven Seas of Rhye ends with: “We can’t know”. Tim Rice’s musings on the lyrics of Bohemian Rhapsody are quoted at length, and space is even found (again) for the views of the Searchers bassist.

Expect plenty of ridiculous tabloid-esque hyperbole. Roger is described as “almost too beautiful”, as if he were some Greek god. Smile’s music is described thus: “… dramatic drums, insistent guitars, strong lead vocals and intelligent harmonies … The overall effect was multi-layered, embellished and breathtaking.”

A much-overused word in music journalism is ‘legendary’. Jones doesn’t disappoint. The Queen logo designed by Freddie is “now legendary”. DJ Alan Freeman’s ‘not ‘arf’ catchprase is similarly “legendary”. Rockfield Studios, where Bohemian Rhapsody was part-recorded, has “legendary status”: indeed it is legendary because Bohemian Rhapsody was recorded there.

To conclude, then, this isn’t the worst book of its type — it is well researched and the author has uncovered some interesting nuggets — but the reader should nevertheless be prepared for the sensationalism and hyperbole typical of the tabloid journalist rather than the objective, dispassionate approach of the serious writer.

Let’s finish with three examples of pure-grade drivel. After stating that Brian and Roger soon came round to the name ‘Queen’, Jones says this: “The point being that no male could be more macho, more straight nor more besotted by women than these two.” As for Queen’s response to the arrival of punk: “There was only one thing for it,” says Jones — the “only one thing” she refers to was not to adapt to the changing times but to tour North America supported by Thin Lizzy. And finally, an extremely tenuous connection between Queen and David Essex, involving Mel Bush — he managed Essex at the time of the singer’s Gonna Make You a Star hit and then promoted a breakthrough Queen tour in 1974 — is described by Jones as a “bizarre twist of fate”. Bizarre, indeed.