Johnson at 10 Book Review

I don’t normally bother with books like Johnson at 10. It’s not that I don’t like politics. Far from it. I have followed politics and read political history all my adult life. Political philosophy, political ideologies/theories (liberalism, conservatism, socialism etc) and books about future policy direction interest me more and more. But I have no time these days for the day-to-day knockabout stuff (particularly PMQs and the BBC’s Question Time programme). I also tend to steer clear of books about what we might term ‘contemporary history’ – that swampy middle ground between modern history and current affairs.

Much journalistic commentary – however insightful the writer – is inevitably contingent and quotidian, quickly superseded by events. Tomorrow’s chip paper. That’s why, though sorely tempted, I resisted buying anything published about the Trump presidency during his time in office (I am thinking particularly of the Michael Wolff books, each of which caused a huge stir at the time).

Anthony Seldon and Raymond Newell try hard to give Johnson at 10 the feel of a work of history. The book opens with a three-page comparison of Johnson and David Lloyd George, there are several references to Seldon’s 2021 co-authored The Impossible Office: The History of the British Prime Minister, and the book closes with an assessment of Johnson’s premiership against – in the authors’ judgement – the nine ‘great’ prime ministers. (The nine are Walpole, Pitt the Younger, Peel, Palmerston, Gladstone, Lloyd George, Churchill, Attlee and Thatcher.)

But it is hard to escape the sense that it’s all a bit rushed and too close to the events themselves. Johnson at 10 was published on 4 May 2023, less than a year after Johnson announced his resignation. Shoddy proofing and other errors don’t help matters.

Here’s an example: “Having inherited a fragile minority government with a majority of 317, Johnson was now attempting to rule with fewer than 300 MPs.”

Here’s another: “Less surprisingly, given his experience as foreign secretary, he had little idea in his first year about Britain’s place in the world.” Surely that should be ‘more surprisingly’?

I also dislike the practice of using asterisks instead of expletives.

The authors argue in their introduction that contemporary history is important because “we can learn from the recent past while memories are fresh, recapture the truth of events and hold governments to account”. Well, yes, but I question the value of on-the-record quotes from, for example, Michael Gove. He was Johnson’s longtime colleague and rival, a key member of Johnson’s Cabinet, an important player in Johnson’s eventual resignation and – possibly at the very time he was interviewed for the book – a member of a successor administration. It’s fair to say that Gove will have weighed his words with particular care.

There is also liberal use of direct speech throughout the book. Chapter four, for example, opens with a ‘conversation’ between “[t]wo weary figures, prematurely aged, sit[ting] opposite each other in the prime minister’s study” in November 2020. The authors tackle the inclusion of direct speech in their introduction: “The quotations, which were always related to us by interviewees, aim … to capture the spirit of the conversations.”

To be honest, I don’t expect to encounter direct speech in a book purporting to be a work of history unless it is from a recorded conversation. Good historical fiction complements history writing, but it is a separate craft and the distinction between the two should not be blurred. I have written elsewhere about a tendency for ‘popular’ history (ie books written for the intelligent general reader) to stray worryingly close to historical-fiction territory.

Anyway, notwithstanding all of the above, I found Johnson at 10 an enthralling read. It’s not, after all, as if we need a few decades to elapse before we can get a proper sense of perspective on the Johnson administration. Seldon and Newell are not rushing to judgement about the big picture. The jury isn’t out. Would anyone of genuinely disinterested mind argue against the point that the 2019–22 Conservative government of Boris Johnson was utterly chaotic and shambolic?

Which is why – cards on the table – I bought the book: I wanted to lap up all the grisly details about Johnson’s downfall and disgrace.

And yes, it is either ‘Johnson’ or ‘Boris Johnson’. It is not ‘Boris’.

His resignation statement of 9 June 2023 (ie when he resigned as a member of parliament before the publication of the Privileges Committee’s report on him but after he had been given an advance copy of it) reminds us that there are at least two Johnsons.

The first is the Johnson who likes to be known as ‘Boris’. This Johnson is whimsical and irreverent, exploiting his felicity with language to beguile us with imaginative and often amusing metaphors (my favourite is probably his various riffs on ‘cakeism’). It is the Johnson who deliberately ruffles his hair before going in front of the camera, the Johnson who casually tells Northern Irish businesspeople to throw customs-related paperwork into the bin. Booster Boris, Boris the buffoon, desperate like a clown to make people smile.

The other is the Johnson who wrote the resignation statement, which is bitter, splenetic and bearing only a tangential relationship with the truth. This Johnson is ruthless, spiteful and utterly self-centred.

In fact, as the book shows, there are at least two more Johnsons as well. The first, as demonstrated over Ukraine, can be fully engaged, up to speed (more or less) with the detail and capable of genuine leadership. The second is a man hopelessly lost in the detail, semi-removed and fatally lacking in leadership qualities.

So sit back and enjoy page after page of the authors’ damning verdict on Johnson’s unfitness for office. Here are a few random examples from one day’s reading:

He swayed like a willow in the wind, bending to the preferences of all he wished to please then meekly backing down when confronted on the feasibility, detail and trade-offs. Often unserious, unable to focus for long and lacking any kind of grip on the machine, his mentality was ill-equipped for the task of governing for an extended period. (page 373)

…he was hopeless at understanding how to convert his woolly dreams into substance. (page 384)

But Johnson didn’t ask [about how to create a better impression with the Americans], it was not his way to enquire, and carried on making the same mistakes. (page 385)

“…we had to keep the PM out of the negotiations as much as possible. He didn’t understand them. He wouldn’t read the papers. He was constantly shifting positions…” (page 400 – a quote from Dominic Cummings)

The fault was not the deed itself [Brexit], but the implementation by Johnson, his lack of drive and sense of purpose. (page 411)

It is a salutary reminder that, as a parliamentary democracy, the way we choose our prime minister – the nation’s leader, the head of the government and probably the most powerful person in the country – is deeply flawed. The general public have no say, unless the leadership contest coincides with a general election (and even then, strictly speaking, we vote to choose our constituency MP). Our prime minister is almost always whoever happens to be the leader of the largest political party in the House of Commons. This person is chosen by (at most) the party’s membership and perhaps only – as was the case with Rishi Sunak in October 2022 – by the party’s MPs.

Indeed, in the case of Sunak, there wasn’t even a vote by Conservative MPs. Boris Johnson chose not to enter the race and the only other candidate, Penny Mordaunt, withdrew just minutes before the deadline for nominations. Sunak became PM because nobody stood against him.

This flawed process is why we ended up with the disastrous Liz Truss in 2022. It is why we very nearly ended up with Andrea Leadsom – who? – in 2016, getting Theresa May instead. And it is why the likes of Priti Patel, Kemi Badenoch and Suella Braverman have been talked about as potential prime ministers. All three are popular with the right-wing of the Conservative Party, which makes up the majority of the membership. I glance across to The Lost Leaders: The Best Prime Ministers We Never Had by Edward Pearce – a book about Rab Butler, Dennis Healey and Ian Macleod – and wince.

A sign that contemporary history is a dangerous beast is that I loathe Boris Johnson in a way that I don’t loathe the Genghis Khans, the Stalins and the Pol Pots – to take three random examples of not entirely likeable people – of the past.

It is not the fact that Johnson is a Conservative. I actually used to quite like him. As with many people probably, I first became aware of him from his appearances on Have I Got News for You and warmed to the buffoonish persona. I bought Friends, Voters, Countrymen, a collection of his journalism. Seldon and Newell tell us that if there is such a thing as ‘Johnsonism’ it can be summed up as: grand projects, levelling up and patriotism. Well, I rather buy in to at least two of those three.

Nor is it that he is a mass of contradictions. The old Etonian and Bullingdon Club member who claims to stand for ordinary folk against the privileged elites; the gifted orator who can light up a room with his words and yet fails to construct a compelling argument; the sharp intellect who gets hopelessly lost in the detail.

It is not even the fact that his administration was so hopelessly inept. I wrote in my 2020 blog British politics and failures of leadership that Theresa May “played a fiendishly tricky hand badly, like a poor poker player on a run of rotten luck” when she was prime minister, and the less said about Liz Truss’s forty-nine days in office the better. But is there any doubt that Johnson will go down as one of Britain’s worst prime ministers in the history of the office?

No.

But the reason why I loathe Johnson is because of the damage that – through his repeated lying and his cavalier disregard for our democratic institutions and processes – he has done to the political fabric of the country. And I have little time for the many members of the Conservative Party who, knowing full well what Johnson was like, chose him as their leader anyway because they assumed he was a winner.

Here’s an extract about Johnson from the diary of Sir Alan Duncan. When Duncan was appointed to the Foreign Office by Theresa May in July 2016, Johnson was the foreign secretary, and therefore Duncan’s boss, until he (Johnson) resigned almost exactly two years later. Although the two men got on reasonably well during their time together, Duncan had little regard for Johnson’s abilities as a serious politician. He says this of Johnson – and plenty more besides – in his entry of 24 September 2017:

I have lost any respect for him. He is a clown, a self-centred ego, an embarrassing buffoon, with an untidy mind and sub-zero diplomatic judgement. He is an international stain on our reputation. He is a lonely, selfish, ill-disciplined, shambolic, shameless clot.

from In the Thick of It by Sir Alan Duncan

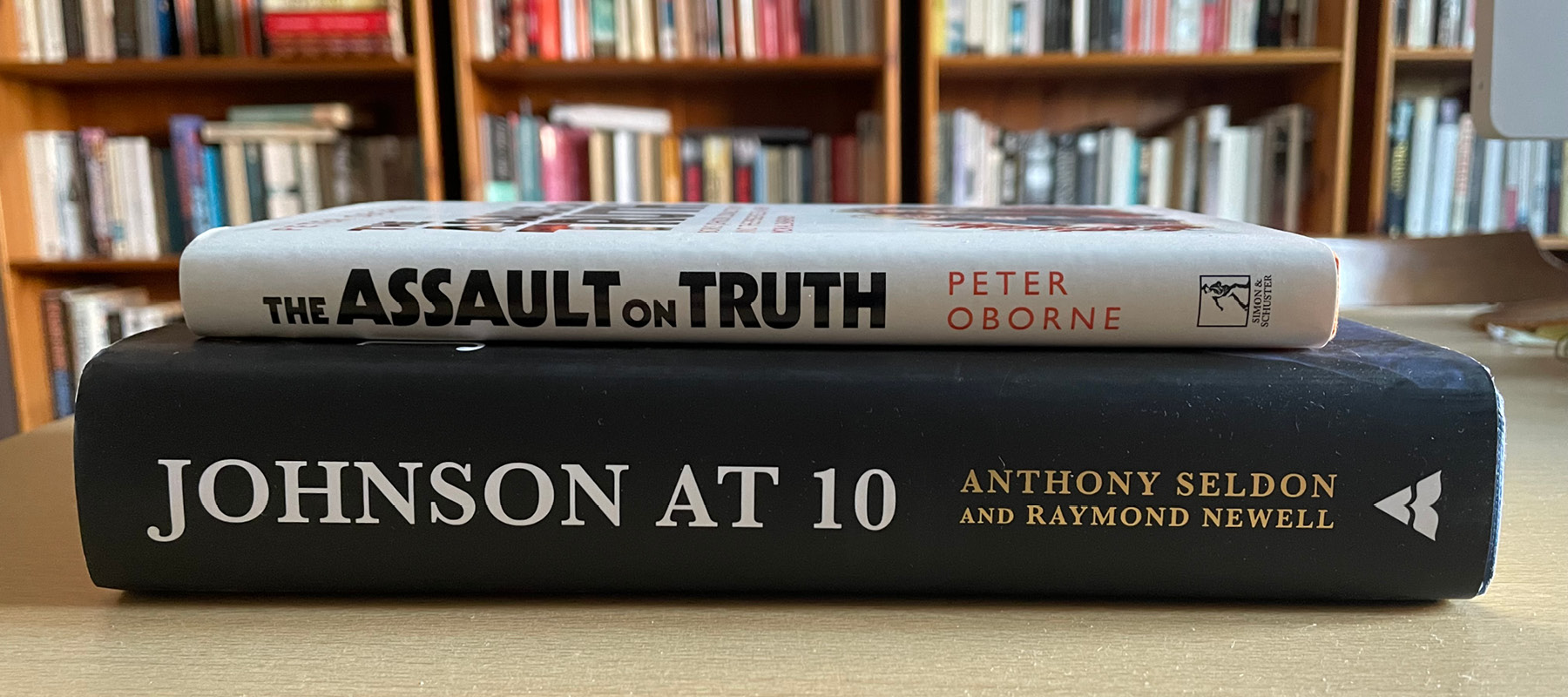

And that is why, back in June 2021 (I think), I bought The Assault on Truth by Peter Oborne, despite its being another of those books destined to quickly date. Oborne does a fine job of systematically setting out the evidence of lying by Boris Johnson and his ministers and political cronies (and to a lesser extent Donald Trump in the USA).

The most important parts of the book are where Oborne explains the damage that political lying — the catch-all term he uses to cover deceit and message-manipulation as well as the telling of out-and-out porkies — does to the public realm, to public trust in our political process, and to the norms, conventions and institutions that constitute the bedrock of our system of liberal democracy (I am thinking here of parliament, the separation of powers, the impartiality of the civil service, freedom of speech and the rule of law).

Johnson wants to be a latter-day Winston Churchill and has written a biography of him. (I highly recommend the review written by the historian Richard J Evans in the New Statesman). This paragraph appears in Innovation, the final volume of Peter Ackroyd’s history of England, published in 2021 when Johnson was prime minister. It is a delicious slice of Ackroydian mischief:

According to the National Review, Churchill’s act of treachery [crossing the floor of the House to join the Liberal Party] was typical of “a soldier of fortune who has never pretended to be animated by any motive beyond a desire for his own advancement”. The accusation of egotism would be repeated throughout Churchill’s career, along with the related charges of political grandstanding and of an addiction to power. Civil servants complained that Churchill was unpunctual, prey to sudden enthusiasms, and enthralled by extravagant ideas and fine phrases. He was a free and fiery spirit who inspired admiration and mistrust in equal measure. Allies hailed him as a genius, while his enemies regarded him as unbalanced and unscrupulous.

from Peter Ackroyd, The History of England Volume VI: Innovation

And, as with Ackroyd’s description of Churchill, it is impossible to read Simon Heffer’s description of Benjamin Disraeli in his book High Minds: The Victorians and the Birth of Modern Britain and not imagine that he had Johnson in mind when he wrote it. It is telling that, in his evaluations of the two titans Gladstone and Disraeli, the arch Conservative Heffer is so full of admiration for the former (a Liberal) and so scathing about the latter.

Here’s a flavour from page 269:

The two men exemplify the Victorian political mind at its best and worst: Gladstone the man of principle, even if he had to engage in occasional contortions to try to remain principled; and Disraeli the opportunist, craving power for its own sake and not because of any great strategy to transform Britain and … willing to throw away any principle in order to stay in office.

quoted from High Minds: The Victorians and the Birth of Modern Britain by Simon Heffer

Some of the above first appeared in a books, TV and films blog I wrote between 2020 and 2022.