Books, TV and Films, May 2021

1 May

In 2019 a Guardian writer described a particularly tricky challenge for filmmakers attempting to portray the subject of poverty convincingly: “Go too far one way and you are accused of romanticising hardship; head in the opposite direction and you’re poking sticks at poor people for entertainment.” In other words, at one end of the spectrum is an overly romanticised nobility-in-poverty view of the hardships of living with little or no money; at the other end is exploitative ‘poverty porn’ à la Channel 5.

The tough-to-watch Ray & Liz gets it spot on, helped by the fact that elements of the story apparently incorporate director Richard Billingham’s own childhood experiences. It is a harrowing depiction of the devastating impact of poverty on people’s lives, with children of course suffering the greatest harm. There is no nobility in poverty here. Just squalor, desperation and neglect. This viewer struggled to feel any sympathy for the parents; it certainly wasn’t the film “full of love” that the Observer newspaper’s reviewer Wendy Ide apparently watched.

5 May

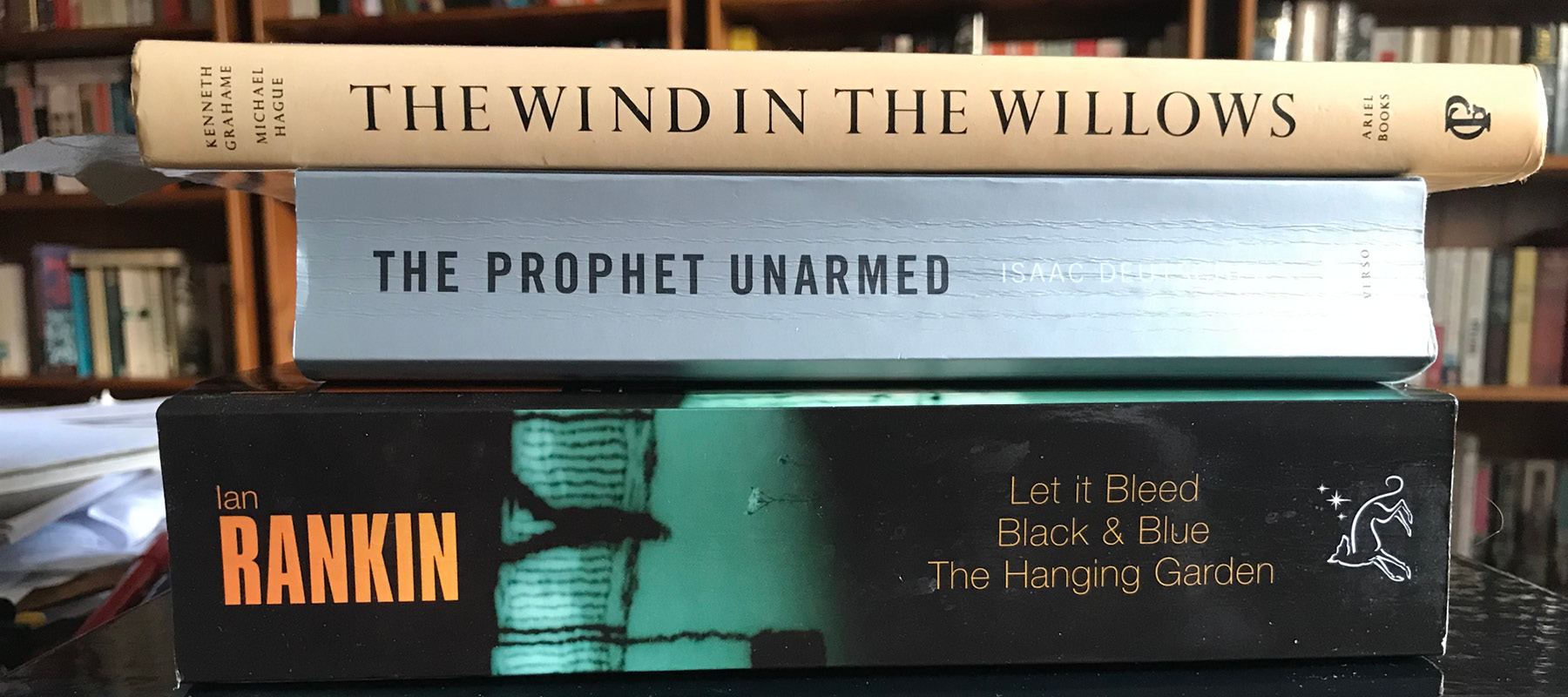

Back to Scotland. Back to Rebus. Another title taken from a Rolling Stones album and suggestive on several levels — this time it’s Black & Blue. The book itself is on a grander scale than the previous Rebus novels. For starters it is considerably longer. It also has a much broader geographical sweep, encompassing Glasgow, Aberdeen and the off-shore rigs, and the Shetlands as well as Rebus’ usual Edinburgh stomping ground.

My copy of Black & Blue is the second of a three-book omnibus called The Lost Years. But cutting through the familiar fug of cigarette smoke and whisky fumes is something brighter and more optimistic. Rebus himself is reacquainted with an old friend DI Jack Morton and for a significant portion of the book keeps off the cigarettes and alcohol. It will be fascinating to see where Rankin takes Rebus in the next instalment, The Hanging Garden.

11 May

The Prophet Unarmed, the second volume of Isaac Deutscher’s classic biography of Leon Trotsky, covers the period from 1921 to Trotsky’s banishment from the Soviet Union in 1929. Much of what occurs in the book flows from three key moments: the ban on factionalism imposed at the Tenth Party Congress in 1921, the introduction of the New Economic Policy (a hugely controversial U-turn by the Bolsheviks, which permitted the return of a small-scale private sector in agriculture) and the incapacitation through ill-health and then death of Lenin.

The ban on factionalism was introduced in an attempt to ensure unity at a time when the survival of the revolution itself was gravely imperilled. The effect, of course, was to stifle all legitimate debate, deliberation and argument. Whoever was in charge of the machinery of decision-making effectively controlled the levers of power as well. As general secretary of the party, that person was Stalin. Those who challenged or questioned the ‘correct’ line were described as ‘deviationists’, ‘oppositionists’ and ‘counter-revolutionaries’.

For a movement obsessed with history — particularly the French Revolution — the past itself increasingly became a battleground. Truth was now a weapon of war, to be used and abused in the struggle for power. It began with a rewriting of the events of 1917 to hide the real attitude adopted by Zinoviev and Kamenev, who were by now allies of Stalin against Trotsky:

This was done timidly at first, but then with growing boldness and disregard for truth … This version was so crudely concocted that even the Stalinists received it at first with embarrassed irony. But once put out, the story began to crop up stubbornly in the new historical accounts until it found its way to the textbooks, where it was to remain as the only authorised version for about thirty years. Thus that prodigious falsification of history was started which was presently to descend like a destructive avalanche upon Russia’s intellectual horizons…

The Prophet Unarmed, Isaac Deutscher, p128

It makes for sober reading when — one hundred years later — the very concept of objective truth is again seemingly up for grabs, when facts are routinely ignored or falsified, and when history is subject to manipulation, oversight and control, and not just in parts of the world under authoritarian rule.

15 May

These 9pm dramas are becoming an enjoyable habit. ITV’s new ‘psychological thriller’ Too Close was perfectly pitched — three episodes, roughly 45 minutes each, showing on consecutive nights. Long enough to add depth but not so long that it starts to overstay its welcome by losing coherence or simply running out of legs (Killing Eve springs to mind at this point).

It maybe stretched credibility once or twice — Connie seemed to have uncanny mind-reading abilities in the way she deconstructed Dr Robertson’s private life in a matter of minutes — but the one-on-ones were good (I had read that people who like the long interviews in Line of Duty would like this too), the portrayal of a psychotic breakdown was excellent and the two central performances by the ever-reliable Emily Watson and Denise Gough were outstanding.

22 May

I have never — either as a child or as an adult — been much of a reader of classic children’s literature. Not for me the likes of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Black Beauty and Treasure Island. I read The Railway Children for the first time in my thirties and Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in my forties — and in both cases not just for enjoyment. In the case of Alice, I was curious about the character the White Queen and whether there are any lyrical connections with White Queen (As It Began), which is one of my all-time top three favourite Queen songs.

As for The Railway Children I wanted to know more about any political undercurrents in the text and, in particular, what additional light the book sheds on the circumstances surrounding the imprisonment of the children’s father; the (wonderful) film always seemed to me, remembering it from childhood, somewhat vague on this point. It was published as a novel in 1906 and the author, Edith Nesbit, was an active socialist. The Dreyfus Affair — the imprisonment in France of a Jew falsely accused of spying — had been a cause célèbre on the European left since the late-1890s. There are also anti-Tsarist references in the book; Nesbit was presumably writing it at about the time of the Russo-Japanese War and the revolution of 1905.

Having recently been given a nicely illustrated edition of The Wind in the Willows (another Edwardian novel, written by Kenneth Grahame and published in 1908), I have enjoyed meeting and learning more about characters like Mole, Rat, Toad and Badger whose names have always been familiar despite me never having read the book before. It’s a beautiful read, so full of imagination and innocence (though here and there faintly unsettling too), an escapist delight in these difficult and turbulent times.

I was sold even before the end of page one: “So he scraped and scratched and scrabbled and scrooged, and then he scrooged again and scrabbled and scratched and scraped…” The contents page confirmed a vague music trivia recollection about the first Pink Floyd album, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn. This and Wayfarers All are my two favourite chapters (so far at least), lyrical, enchanting and mystical.

25 May

Action-hero movies are one of my guilty pleasures — usually after several pints, when I don’t feel quite so guilty. Is John Rambo perhaps the tough guy’s tough guy? The Rambo franchise has been around for an unbelievable forty years. Sylvester Stallone is now in his seventies but still manages to kick some serious bad-guy ass.

Rambo: Last Blood is depressingly familiar fare (in other words, genre fans will love it), this time with an extra dollop of sadistic violence on top. The plot — Mexican cartels forcing Rambo’s adopted niece into sexual slavery — seems to be pitched fairly and squarely at Trump devotees, though they surely can’t be happy that after nearly a full Trump term it was so goddam easy for the slimeballs to cross the border. Build that wall!

It’s all a long way from 1982’s First Blood — the first and by far the best Rambo film — which, for all the opprobrium that came its way after the release of the follow-up in 1985, was actually a thoughtful depiction of a country still struggling to come to terms with the Vietnam War as well as being a thrilling survival/chase movie. Nobody in First Blood is actually killed, and yet I remember a newspaper op-ed (I think in the Daily Mail … enough said) after the Hungerford massacre of 1987 declaring that First Blood would never again be shown on British television.

28 May

The quality TV crime dramas just keep on coming. Marcella, Line of Duty, Unforgotten, Grace, Too Close. My latest binge-fest is Innocent. Series two is showing at the moment and (yippee) series one is still available for free on the ITV Hub.

Two-and-a-bit episodes in and Innocent is another well-constructed and enjoyable storyline that treads (admittedly very) familiar ground — a family man sentenced for murdering his wife, a possible miscarriage of justice and a tangled web of secrets, deceit and cover-ups. Innocent is particularly strong on the devastation that traumatic events visit on the survivors; as the police investigation reopens, it doesn’t take long for the brittleness of patched-up and patched-together relationships to become apparent. It equally quickly becomes clear that the title refers as much to the family’s teenage children as it does to the convicted husband.

The least credible aspect — and for me an unnecessary plot complication — is that the senior officer appointed to lead the new police investigation is in what appears to be a not altogether convincing secret relationship with the senior officer who led the original investigation and whose I-know-the-bastard-did-it-really dereliction of duty she quickly uncovers.