In Praise of Gyles Brandreth

The Times once referred to Gyles Brandreth as “the Marmite of light entertainment”. Let’s explore that via a word game (Gyles loves word games). Here we go: How many words can you think of in ten seconds that describe Gyles Brandreth and that begin with the letter ‘s’?

Well done if your list didn’t include at least one of these adjectives: silly, smug, smarmy.

My guess is that most people will ‘know’ Gyles from daytime and/or early-evening television. He is currently a regular contributor to ITV’s This Morning, fitting snugly into that tabloid-esque environment, with its bright colours and celebrity sparkle, its bite-sized segments and its cast of bubbly characters.

Whatever the particular role he chooses to play – the clownish entertainer, the nerdy-but-nice know-it-all – Gyles comes across as the epitome of safe, wholesome, middle-of-the-road appeal. He is light-hearted, quick-witted and gossipy, and with a child’s sense of fun.

Not to mention shamelessly, drippingly oleaginous when it comes to the rich and famous – the royals above all.

The iron law of good taste dictates that as I loathe Marmite so should I loathe Gyles. And yet I don’t. In fact, I like him…a lot.

Actually, I admire him. Gyles is a nice guy, a fundamentally decent human being who has led an incredibly busy and purposeful life. He reminds me, in that sense, of Brian May, whose own expertise and activism ranges from astrophysics and animal welfare to stereoscopy and, of course, music.

But there is also another reason why I like and admire Gyles, one bathed in the warm glow of nostalgia. He is there in some of the mental snapshots that I treasure from my younger days and that are lovingly preserved in an imaginary box labelled Fond Memories. Again, there is a Brian May parallel, though Gyles’s impact on my teenage years is several orders of magnitude less than that of Queen, which I have written about here. But he is an undeniable presence, however fleeting.

I particularly associate Gyles with some of my favourite memories of my mum. And he is a reminder, too, of (generally) happy and (mostly) carefree schooldays – and of one inspirational teacher in particular.

And what connects the three of them – my mum, the teacher and Gyles – is the TV quiz show Countdown.

I inherited my mum’s love of puzzles and quizzes. She was very good at both, though I suspect her general knowledge would have been better if she had been more adventurous in her reading choices. What she didn’t pass on was her ability to decipher cryptic crossword clues. I am much more like my dad in that regard, content to lock horns with the much less intimidating quick crossword. But we were all fans of game-show staples of the 70s like Ask the Family, Call My Bluff and A Question of Sport.

Which explains why my mum and I were sat in front of the TV at 4.45pm on Tuesday 2 November 1982 as Richard Whiteley said the words “As the countdown to a brand-new channel ends, a brand-new Countdown begins”. It was the launch of Channel 4 – the first new television channel in my lifetime – and, what really mattered for us, of a new game show, one based on letters and numbers.

We were instantly hooked, and it became our regular go-to programme at teatime (‘tea’ in this case meaning the main meal of the day. What we called ‘dinner’ – ie a midday meal – most people now refer to as ‘lunch’). And this is where Gyles Brandreth comes in: he was a regular in Dictionary Corner.

In its earliest days Countdown featured a ‘hostess’ who displayed the numbers and letters, and there was a revolving cast of numbers experts (usually Carol Vorderman but at least one other – Whiteley called them ‘vital statisticians’) and lexicographers. Each lexicographer seemed to be around for a week of episodes (presumably one day of filming), but my recollection is of the celebrity guest alongside them in Dictionary Corner sticking around for a lengthier residency (an entire week of filming, perhaps?).

Muddled memory time: I always thought of Gyles as the second occupant of Dictionary Corner after Kenneth Williams, until I was reminded – I think after reading Richard Whiteley’s autobiography, Himoff! – of Ted Moult, who apparently did a week or so at the very beginning.

I was in lower sixth doing A levels at the time, just starting to figure out what my academic interests were and what I was actually good at. Two teachers, in particular, made a lasting impression: Mr Taylor, who taught me history (which I went on to study at university), and Mr Scholes, who taught Latin.

Mr Scholes combined the charismatic appeal of Sidney Poitier’s Mr Thackeray (To Sir, with Love), the eccentricity – though certainly not the ineptitude – of Will Hay’s schoolmaster character, and the love of language of Robin Williams’s Mr Keating (Dead Poets Society). His lessons may have been sketchily planned and lacking in formal structure, but they were stimulating, academically rigorous and – more often than not – great fun.

As he led us through poetry and prose by the likes of Virgil, Ovid and Tacitus, Mr Scholes taught us to love learning. One of my favourite tales was of how as a student he preferred working in a cold room (I pictured an austere garret with a tiny electric heater in the depths of winter) and sitting on a hard chair to keep him mentally alert as he studied late into the night. (The strategic placement of a drawing pin on the chair to prevent him slouching was perhaps one tall story too far.)

Above all, he taught us to love words. His weighty, dog-eared Latin–English dictionary was his bible. He told us of long hours spent poring over entries, paying particular attention to the etymological information and studying the accompanying illustrative quotations to discover new words and alternative usages in both Greek and Latin.

I went home and watched Gyles exhibiting exactly the same passion for words and language in Dictionary Corner, with the Concise Oxford as the Countdown bible – the same dictionary, coincidentally, that we had at home.

Words. If there is one word that comes anywhere close to encapsulating or at least connecting the vast range of Gyles’s passions and pursuits, that is perhaps the one. Words on the page. Words spoken. Wordplay. The after-dinner circuit. The Oxford Union. Awards ceremonies. Dictionaries. Novels. Diaries. Plays. Poetry. The theatre. Radio. Shakespeare. Oscar Wilde. Jane Austen. Winnie the Pooh…

Take a breath…

…Quotations. Anecdotes. Grammar and the use of English. Writing a musical. Setting up the National Scrabble Championships. Writing a biography of Frank Richards (Billy Bunter’s creator). Pitching to revive Billy Bunter on TV. A one-man show at the Edinburgh Fringe.

It is as if the only word Gyles doesn’t know is ‘stop’.

The man has a gargantuan appetite for work. When writing a book, he aims (he tells us) for one thousand words a day, something I find both inspiring (how hard can it be, I kid myself, with a bit of application and self-discipline?) and intimidating, especially when staring (as I do most days) at a blank Word document, a hideously trite phrase or a bland collection of sentences on the screen in front of me. I will gladly settle for one hundred words that I am pleased with. Gyles also once said, I think, that he set aside six weeks to write a novel (Venice Midnight). Great idea for my novel, I thought, before giving up on day three.

(I was unable to track down the specific reference for this titbit but Gyles’s diaries show that he started writing the novel in the middle of June 1997 and attended a lunch to mark its publication in early September. A quote from 19 June 1997: “This week I am writing a children’s book: The Adventures of Mouse Village. Next week I start my novel: Venice Midnight.”)

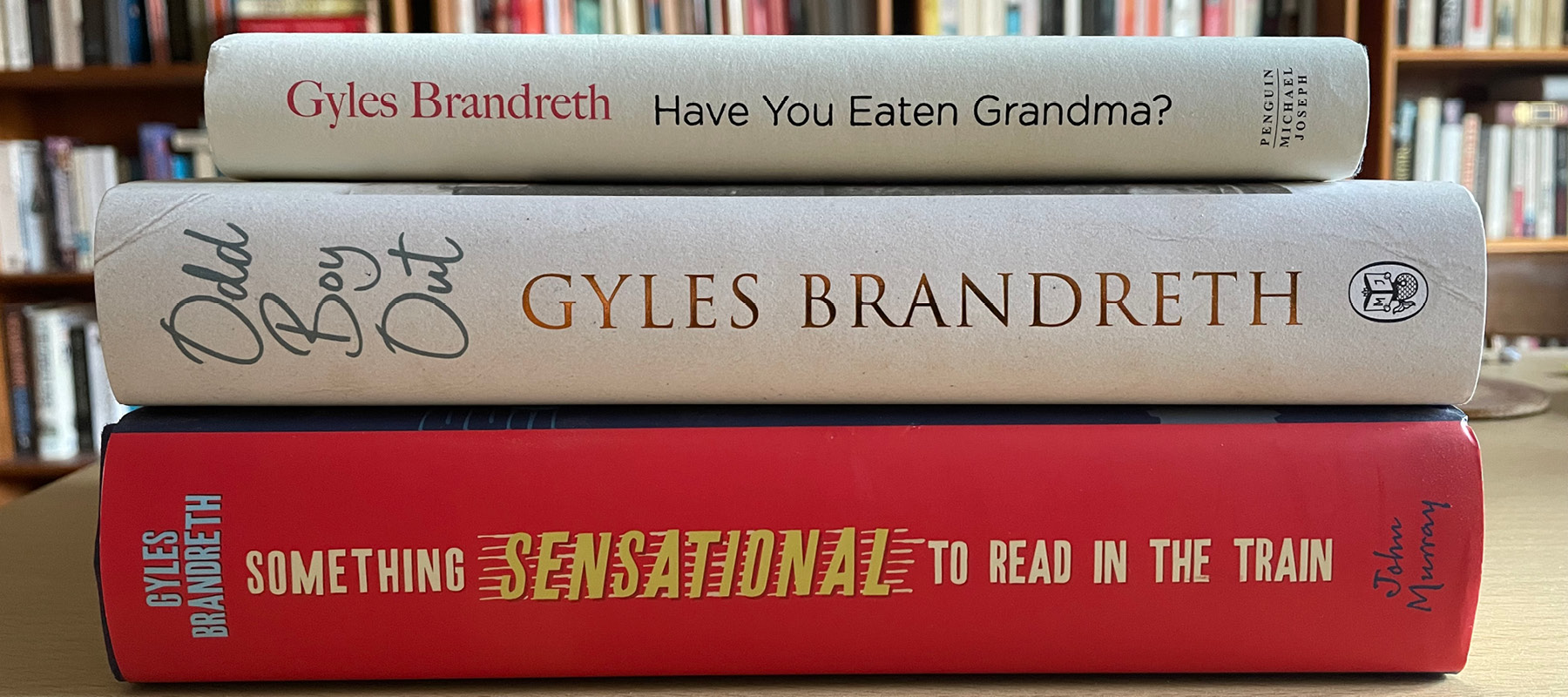

Yes, Gyles has written a detailed diary for much of his life. (Seriously, where does he get the time?) I thoroughly enjoyed both sets of diaries that he has published. Something Sensational to Read in the Train runs from 1959, when he was at prep school, to the turn of the millennium. Breaking the Code, meanwhile, covers his years as an MP, including a period in the whips’ office, and is an excellent insider’s perspective on the 1992–97 Major government.

I couldn’t resist Have You Eaten Grandma (2018), if only because of the editing work I do. There are lots of ‘rules’ governing the use of English that are more or less universally accepted, of course. But there is also an ever-expanding grey area about which there is much less agreement, hence the large number of style guides and books – and websites these days – addressing such rarefied matters. The ones I am aware of are as dry as you would expect (except for The Sense of Style by Steven Pinker). Not so Have You Eaten Grandma, which is excellent for anyone who wants a funny and accessible introduction to writing well, or at least accurately.

In 2019 Gyles published an anthology of memorable poems called Dancing by the Light of the Moon, the title a line from his favourite poem, The Owl and the Pussycat, which he learned by heart as a child. I have a blind spot when it comes to poetry. During the 2020 lockdown Gyles tweeted himself reading a poem every morning, most from memory. I didn’t hear them all, but each one I caught was a delight. The book’s subtitle is ‘How poetry can transform your memory and change your life’. That’s quite the claim and one I really ought to get round to investigating.

A review of Odd Boy Out, Gyles’s memoir

“Do forgive the occasional aside. I’ll try not to overdo it…” Yeah, right. Gyles is a wonderful raconteur and storyteller. He both speaks and writes beautifully – and makes it all seem so effortless. And what’s more, none of it feels contrived. You can hear his voice on every page and believe that all these things really did happen to him, more or less as described. Odd Boy Out (published in 2021) is often laugh-out-loud funny and wonderfully – shockingly – indiscreet.

In the prologue he unleashes a first-rate anecdote about the Queen, the Duke of Edinburgh and male strippers from the time he sat with them (TRHs – not the strippers) in the Royal Box at the Royal Variety Performance. Yes, really. On to some family history in chapter two (never my favourite bits of biographies and memoirs; I am hopeless with family trees) and suddenly the reader is knee-deep in a tale about Donald Sinden. And it doesn’t let up.

We are, he says, moulded by our parents. Are we surprised that Gyles loves anecdotes when his father “measured out his life” in them? Is it any wonder that he knew large chunks of Milton at the age of six when his father performed dramatic dialogues at his bedside while his mother read him nursery rhymes? Unlike some who rebel against or recoil from the circumstances of their upbringing, Gyles embraced it all.

I always used to think of Gyles as quintessentially, comfortably, smugly middle class. It’s how he himself, in Odd Boy Out, characterises his childhood. But it came at a cost – literally. There was never enough money. To quote Gyles, money worries wore his father down and then wore him away. Perhaps if the children hadn’t all gone off to boarding school (three to Cheltenham Ladies College and one to Bedales) or if the family hadn’t spent so much time in Harrods, things might have been different.

Gyles is a show-off, a showman and a shameless namedropper – the latter a reminder that he really has met just about everybody (there’s a nice recurring ‘I shook the hand that shook the hand…’ line in Odd Boy Out). And he can certainly do silly – he is something of an expert at standing on his head, a skill which he has demonstrated in some rather unlikely places. He’s a bit too full-on at times. And then there are the jumpers and the teddy-bear museum. As I suggested above, it’s a fairly safe bet that adjectives like smarmy, superior and too-clever-by-half have attached themselves to his name on a not infrequent basis over the years.

In Gyles’ defence it is something that he readily acknowledges. This is how part two of Odd Boy Out begins:

I realise now that I must have been a ghastly child. I was insufferable: precocious, pretentious, conceited, egotistical.

But one of the many joys of Odd Boy Out is that, as we turn the pages, we get to know the other Gyles, the one that doesn’t make an idiot of himself by wearing a silly jumper and standing on his head. So there is plenty of sadness, regret, guilt and self-criticism in these pages alongside the laughs, jokes and tall tales. And he’s the one tapping the keys to write the final chapter, which takes the form of a letter to his late father and which movingly brings together the different strands of the story he has delighted us with over the preceding 400 pages.

Except…that’s not quite the end. There’s a short epilogue, which begins with his wife Michèle knocking on the study door. How odd, because the prologue begins with his wife popping her head around the study door: “She never knocks. She likes to keep me on my toes.”

Perhaps we can’t quite believe it all.

Anyway, a happy belated (very – 8 March) seventy-fifth birthday to Gyles Brandreth.

Some of this content first appeared in a books, TV and films blog I wrote between 2020 and 2022.