Books, TV and Films, May 2020

Wednesday 6 May

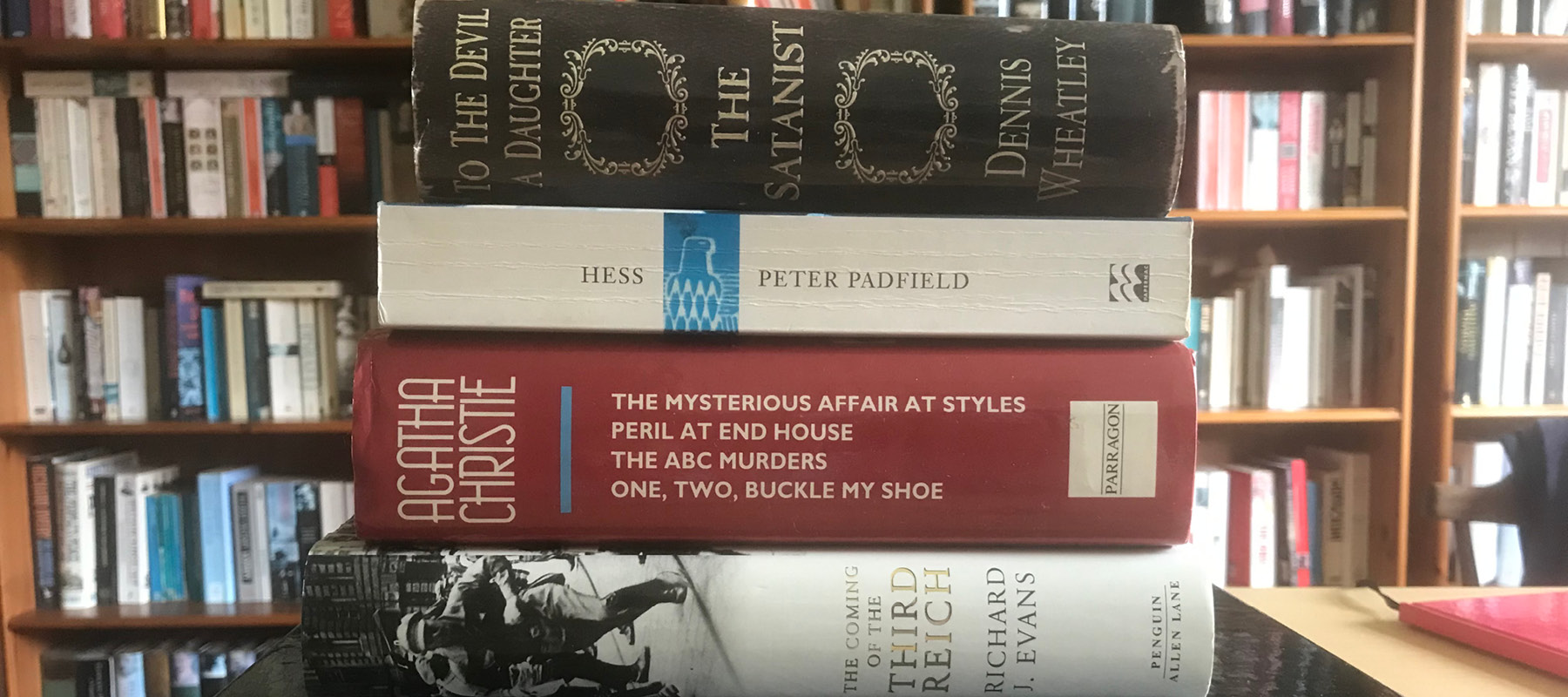

I finished two things today: Homeland on Channel 4 and the Rudolf Hess biography, Hess: The Führer’s Disciple.

I stayed up late to watch the final episodes of the final series of Homeland. Eight series in total — and what fantastic television it has been. It began way back in 2011, ten years after the 9/11 terrorist attacks with an ‘is he/isn’t he a terrorist’ plotline featuring Damian Lewis. Like all long-running dramas, it has suffered from a bit of a credibility problem as time passes and yet another apocalyptic crisis confronts the central characters. But it is well worth suspending disbelief and letting yourself be swept along.

As well as offering gripping drama and jaw-dropping twists and turns, Homeland has had a brilliant writing team with an uncanny ability to deliver a succession of stories foreshadowing the next ‘big thing’ in global politics — not just foreign and domestic terrorism, but also Russian interference, governmental overreach and abuse of power, and (in series eight) a fatally flawed US president.

Peter’s Padfield’s Hess biography, meanwhile, is easily the least enjoyable book I have read for some time, though it did improve as it went along. I wrote last month that it was a bad biography badly written. I was perhaps being a little unkind about the writing — but not about the biography itself. This is a bad book.

It doesn’t help that the biographical subject, Rudolf Hess, completely lacked personality and profile. That was his nature: Hitler’s yes-man, always in the shadows and utterly obedient. The first third of the book, covering the years to 1941, is frankly a waste of time. Hess was theoretically the Deputy Führer but either there is nothing to write about (which clearly isn’t the case for someone in such a prominent role) or Padfield has been unwilling to do the necessary spadework.

There are just two chapters covering the years 1933 to 1939. The first, called The Night of the Long Knives, barely mentions Hess at all. The second, The Deputy, is just 14 pages, much of which is actually about antisemitism.

It would surely have been better to have marketed the book around what it is actually about — Hess’s flight to England. On this, however, it is full of speculation, guesswork and conjecture. Padfield, presumably writing in 1990–91, frequently refers to government files closed until 2017 to excuse the lack of definitive answers to key questions about Hess’s actions. My edition includes a 30-page Afterword relating to these files (which he informs us were all opened — unexpectedly, one assumes — in 1991 and 1992). It opens with the words: “The expectations raised by this torrent of releases were … not met: there were no revelations …”. Ah, shame.

10 May

Time for something a little less intense: another Poirot, Peril at End House. I wrote about the very first Poirot novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, last year. End House is the fifth in the series, published in 1932, 12 years after Styles.

One of the points I made about the Styles book is that Poirot didn’t yet strike me as the fully drawn character we know from TV and film. End House offers us a more recognisable Poirot, not least his enormous self-regard. I also commented on Agatha Christie’s use of language and the underlying attitudes and beliefs it reveals, particularly regarding race and class. In End House, a wealthy friend is described by the character Nick as follows: “He’s a Jew, of course, but a frightfully decent one.” Consider, too, this from Poirot himself on a suspect: the reaction of Ellen [a housekeeper] “might be due to natural pleasurable excitement of her class over deaths.”

I did smile at this comment from Poirot: “When you have eliminated other possibilities, you turn to the one that is left and say — since the other is not — this must be so …”. Now why does that sound familiar?

12 May

The central claim of the Padfield book is that Hitler knew in advance about (and therefore approved of) Hess’s flight to Britain in 1941, a highly controversial claim. The first thing I do when reading dodgy claims is to see what acknowledged experts have to say. Step forward Richard J Evans, professor of modern history at Oxford. The Third Reich at War states unequivocally that Hitler knew nothing of the flight in advance. Now who to believe?

Evans has published a trilogy on the Third Reich, about 2000 pages in total. It will be quite an undertaking but this seems like a good moment to tackle the complete trilogy, so I have started the first book, The Coming of the Third Reich, the one that I read when it came out in 2003.

16 May

Not sure why but I got the urge to watch Salem’s Lot, borrowed from a friend (it’s perhaps because I was reminiscing not too long ago about horror books from childhood days). I read a number of the early Stephen King books as a teenager — The Dead Zone, Carrie, The Shining. Salem’s Lot was one of them too, but it’s the TV dramatisation that really left a lasting impression.

I originally watched it when it was shown on the BBC, presumably sometime around 1980, soon after it was made. It stars David Soul, who was a huge name at the time as one half of Starsky and Hutch. This is the full three-hour version (in two parts). I later saw that an abridged film-length version had been released on video. Utter vandalism! Avoid!

Watching it now, the special effects, fashions and so on obviously date it, but it’s a classic of its type and includes some really memorable moments: Danny Gluck scratching at the window; the first appearance of ‘Mr Barlow’ in the family kitchen. It is directed by Tobe Hooper, a Spielberg of the horror world who made his name with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

What’s striking is that so many of the actors are familiar, even if you can’t necessarily name them. Apart from Soul, there’s Bonnie Bedelia (Mrs McClane in the first two Die Hard films), Elisha Cook, yet again playing an unhinged-looking outsider and people like Geoffrey Lewis and George Dzunzda, who have been in just about everything. Just google the names.

Best of all is a memorable performance from James Mason as the vampire’s henchman: “You’ll enjoy Mr Barlow and he’ll enjoy you.” Great stuff.

Back, holy man! Back, shaman! Back, priest!

22 May

I’m making good progress with The Coming of the Third Reich. It’s a pleasure to read a historian like Richard Evans after the Padfield ‘biography’. To be clear, I have no problem with revisionist writers like Padfield, provided that what they write is well argued and supported by evidence. Evans was an expert witness in the famous Lipstadt trial of David Irving (the DD Guttenplan book The Holocaust on Trial is excellent, as is the recent film Denial with Timothy Spall as Irving).

Evans is opinionated, frank (read his obituary of Norman Stone) but also authoritative. Unlike with Padfield, the reader feels in safe hands, confident that the text distils knowledge and understanding built up over a lifetime of study — even if paragraph one of chapter one does state that fifty years elapsed between the creation of the German Empire in 1871 and Hitler’s accession to power in the early 1930s. Yikes!

Evans also writes exceptionally well, notwithstanding the occasional questionable phrase such as “rebarbatively abstruse” (I can’t actually remember who or what he said that about). More puzzling to someone who has read a considerable amount about the Nazis is his decision to render German titles into English: Hitler is referred to as ‘the Leader’ not ‘the Führer’; his book is ‘My Struggle’ not ‘Mein Kampf’ and newspapers have names like ‘The Stormer’ (instead of ‘Der Stürmer’) and the ‘Racial Observer’ (‘Völkischer Beobachter’). Odd.

27 May

Before writing about two horror films I wanted to re-read the original novels, both by Dennis Wheatley. I am in the middle of To the Devil a Daughter (hyphen sometimes included and sometimes not), having read The Devil Rides Out a few months ago. More to follow on the books and films, then. Here I will comment briefly on the writing.

To the Devil a Daughter was written in 1953, much later than The Devil Rides Out (which was published in the mid-30s). Wheatley seems to have toned down the ridiculous overuse of capital letters (though ‘Top Secret’ made me laugh), but that apart nothing much has changed across the decades. As with Agatha Christie, Wheatley’s general vocabulary and choice of idioms — “mumsie”, “no better than he should be”, “in the family way” — speaks volumes about his attitudes and assumptions: his worldview is privileged, hierarchical, male-dominated, white, Christian and at the reactionary end of the conservative spectrum.

Wheatley is clearly no fan of the postwar social-democratic settlement, seeing it as a naked attack on his world of privilege and entitlement. Rationing, for example, represents the overweening power of the state. Consider, too, this observation about taxation. They are voiced by a ‘baddie’, but there is every reason to suppose that the author is in sympathy with the line of argument:

Since … the Government has become only another name for the People, it really amounts to the idle and stupid stealing from those who work hard and show initiative.

He is vehemently anticommunist, of course: the Soviet Union (and communism in general) is the devil’s handiwork, a means by which Satan visits chaos and misrule on the world.