This Time No Mistakes

I uploaded this blog on the day of the 2024 general election, before the results of the exit poll were announced at 10pm.

If he were alive today, Benjamin Franklin would surely have said that nothing is certain in life except death, taxes and political parties refusing to be honest about taxes during an election campaign.

I wrote the bulk of this blog during the days leading up to the 2024 UK general election. Other than the staggering incompetence of the Conservatives’ election campaign, the main talking-point of the last few weeks has probably been the promise made by the two main political parties (joined by the Liberal Democrats) that, if elected, they will not put up any of the three main revenue-raising taxes: income tax, national insurance and VAT.

They have, in other words, embraced each other in a Faustian dance, making ludicrous assertions about the huge sums to be raised from cutting ‘red tape’ (see below for more about scare quotes!) and clamping down on tax avoidance and evasion to justify claims about fully funded plans that require no additional tax rises.

Unsurprisingly, the main manifesto launch week echoed with accusations of a lack of candour and of a failure to be honest with voters about the prospects for the economy, the state of our public services and the scale of the challenges the country faces. Paul Johnson of the Institute for Fiscal Studies – a respected independent voice – has talked of “a conspiracy of silence”.

And no shock, either, that – according to a British Attitudes Survey published last month – trust and confidence in government and politicians is at an all-time low.

Taxes and election campaigns

Let’s briefly rewind thirty years or so, to the beginning of 1992. The economy had been in recession for more than a year, the Conservatives were haemorrhaging goodwill after introducing the poll tax, and the party had ditched Margaret Thatcher, replacing her with the grey, technocratic John Major. Labour was narrowly ahead in the opinion polls and in with a chance of forming the next government.

In January the Conservatives unveiled their ‘Labour’s Tax Bombshell’ poster campaign, followed soon after by ‘Labour’s Double Whammy’ (a reference to more taxes and higher prices). The Conservatives went on to win a fourth term in the April general election.

A followed by B does not mean that A caused B, of course, and it would be ridiculous to pin an election outcome on just one factor. What is not in doubt, however, is the deep scars left by the 1992 defeat – and specifically those Tory tax attacks – on Labour’s collective psyche.

Labour as the party of high taxation is the go-to weapon in the Tories’ election arsenal, one wielded with relish by their many media cheerleaders as well. It is why in the 1997 election campaign Tony Blair and Gordon Brown went big on New Labour’s ‘fiscal responsibility’, promising to stick to the government’s existing spending plans for two years and not to put up income tax for the full parliamentary term.

Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves have been equally cautious. And yet the day after Labour’s 2024 manifesto launch, the front page of the Daily Express warned us not to “fall for Labour’s hidden £8.5bn ‘tax trap'”. The Times quoted Paul Johnson’s comment about a conspiracy of silence and pointed out that the Labour manifesto offered “no assurances on capital gains tax, fuel duty and tax relief on pensions”.

The Daily Mail’s headline was “What is Labour not telling us about tax hikes?” The Mail’s fondness for question marks in headlines reminds me of the adage associated with the journalist Ian Betteridge (though it predates him) that any headline ending with a question mark can be answered with the word ‘no’ – or, in this case, ‘nothing’ or, more likely, ‘not much’.

More broadly, the shallowness of the day-to-day party-political knockabout is why I would not describe myself as a political junkie. Why bother with Prime Minister’s Questions when you can be sure that the prime minister will not even attempt to address the questions put to him or her? (As a side-point, I have been surprised that, given his lawyer background, Keir Starmer has not been more agile on his feet during PMQs in exploiting Rishi Sunak’s evasiveness, almost always sticking to pre-prepared lines.) Why watch the BBC’s Question Time when you already know the script?

Short-termism is democracy’s Achilles heel, an inherent weakness most brutally exposed during election campaigns. Politicians either promise unachievable change in a ridiculously short timeframe (Sunak’s ‘Stop the boats’ pledge a good example, delivered very obviously with the polls in mind) or – the opposite problem – shy away from being frank with the electorate about the sort of remedies required to properly get to grips with the country’s problems (hence the current omertà on tax).

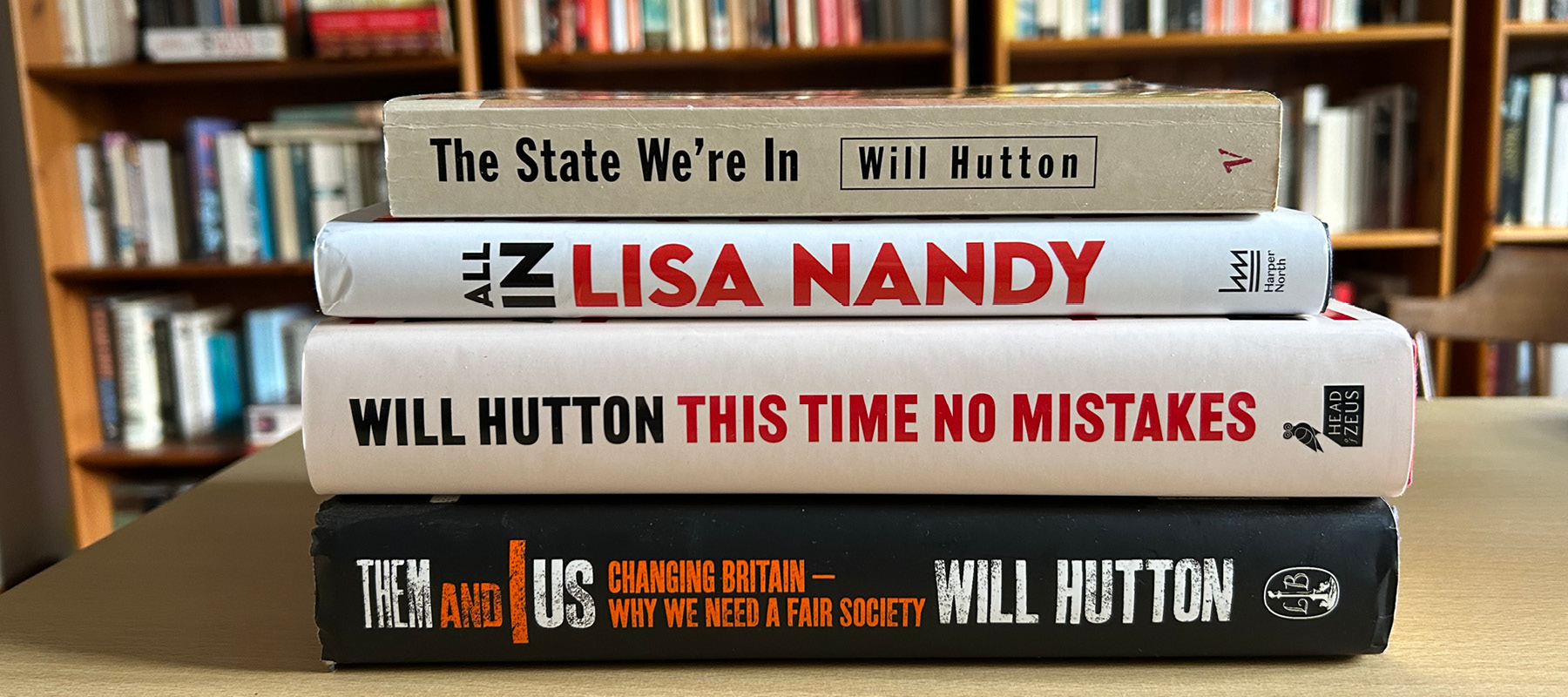

Take the book All In: How to Build a Country That Works by the Labour frontbench politician Lisa Nandy. I am a Nandy fan. Apart from being the MP for the town near where I live, she is smart, an assured media performer and someone with the ability to – cliché klaxon – talk human. It puzzles me why the Labour leadership have all but benched her.

(Nandy was briefly shadow foreign secretary, having come a creditable third in the 2020 Labour leadership election that Starmer won. She was later moved to levelling-up – actually a shrewd appointment, I thought, because her new role was shadowing Michael Gove, the Tories’ most effective minister – and then very obviously demoted to international development, though still in the Shadow Cabinet.)

Nandy’s book is an interesting enough read and – to steal the puff quote from fellow MP Jon Cruddas – she sets out a “positive agenda for change and renewal”. But, as a loyal frontbencher, she cannot and does not stray too far off script, if at all. For all her talk of starting afresh (page 3), Nandy’s thinking remains within the existing (Labour) paradigm.

Shifting the paradigm

It was not Ronald Reagan or Margaret Thatcher but Bill Clinton – champion, along with Tony Blair in the UK, of what came to be called ‘the third way’ – who proclaimed, in his State of the Union address in 1996, that the era of Big Government was over.

What we might think of as the Thatcherite–Reaganite worldview has set the terms of debate about public policy since the mid-1970s. It is the paradigm within which mainstream politics operates. Fear of the perception of governmental overreach – of so-called ‘nanny statism’ – limits what administrations of all hues are willing to contemplate.

The Overton window is a concept used in political science and denotes the range of policies voters will supposedly find acceptable. A policy that is outside the Overton window will not be accepted by the mainstream voting public. Any such policy may be widely seen as extreme or simply as impossible to achieve – and therefore any fundamental rethink of a policy or a set of policies (ie an approach or a strategy) will almost certainly require shifting the Overton window so that what was previously deemed extreme, impossible or unthinkable becomes acceptable, doable and achievable.

The concept is closely linked with the idea of common sense – ie with what instinctively seems right. The reason why Thatcher’s ghost still walks today is because her worldview became the dominant paradigm from the 80s onwards, setting the terms of debate and defining what was seen as common sense in politics and economics.

The political commentator Sonia Sodha has argued persuasively that, in economic policy, “the narratives of the political right are more compelling because they are more intuitive”. Thatcher’s claim that running one of the largest economies in the world was no different from running a household budget, though ridiculously simplistic (and, according to many economists, fundamentally wrong), was easy for voters to understand and seemed to make sense because it aligned with how they lived their lives.

Shifting the Overton window – changing the popular mindset – involves altering the terms of debate. But individuals do not form their worldview in a vacuum. Our thinking – about what is or is not right, acceptable, achievable – is heavily influenced by the media and other opinion shapers. For good or ill, much of the battle to reset the terms of debate needs to take place on this terrain. And it will take time.

Sodha has discussed the notion of the maxed-out credit card. It is a commonly used metaphor in the media and on the political right in arguments about government spending. It seems to make sense. It fits with our everyday experience of having to limit what we spend because we only have a certain amount of money and at some point it will run out.

It would be great if the government could do more to help the poorest, to support families, to improve our public services – but where is the money coming from? Or so the argument goes. There is (to quote another well-worn phrase) no magic money-tree.

But look what happens, says Sodha, when we switch the metaphor. Think of government spending not as ‘partying on the credit card’ but as ‘taking out a mortgage’, something that is equally part of the everyday experience of many people, a commitment that millions of us take on as a sensible long-term investment for the future.

It is time to switch the metaphor. Time to shift the paradigm.

This Time No Mistakes

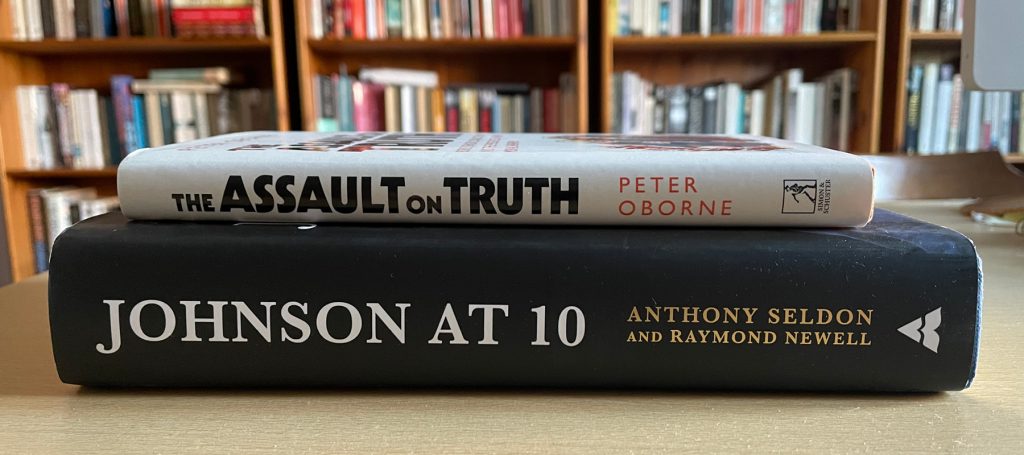

And it is the paradigm shifters who really intrigue me, the thinkers prepared to radically reimagine how we might do things. Which brings us to This Time No Mistakes: How to Remake Britain, written by the author, journalist and political economist Will Hutton, published in April 2024 and then rush-released (presumably) in paperback in the middle of the summer general election campaign.

Hutton has been an influential voice on the centre-left for decades (including as editor of the Observer for four years). He made arguably his biggest splash with his book The State We’re In, published in 1995. Tony Blair – then the leader of the Opposition and on course to be the next prime minister – was apparently impressed by Hutton’s thinking around ‘communitarianism’, which was briefly floated by Labour strategists and policy wonks as the next Big Idea.

Hutton describes This Time No Mistakes as “a life’s work”, an analysis of where it has all gone wrong and a prescription for how to put it right. It is not simply a list of policy ideas for the next government, though the book contains plenty of those. Rather, he sees it as a blueprint to secure the coming decades for social democracy.

A blistering opening salvo on page IX – “the most incompetent, negligent government in modern times” – is followed by a first chapter – On the Edge (the title echoing Rory Stewart’s recent brilliant account of his time as a Conservative MP) – that maps out the enormity of the crisis currently facing Britain.

The next few chapters take us on a whistlestop tour of British and US political and economic history, beginning with the fallout from the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal of the 1930s.

The phrase ‘New Deal liberalism’ is one to which Hutton repeatedly returns, whether in the context of the consensus that prevailed in the West in the decades following the end of the Second World War or its collapse and replacement by a neoliberal paradigm during the era of Reagan and Thatcher.

To recall President Clinton’s words, the era of Big Government was over.

Let’s define neoliberalism as (1) hostility to an active, interventionist state that ‘interferes’ in our lives and limits our ability to act as free individuals in a free market, combined with (2) a belief in the economics of low taxation. Note the popularity in right-wing discourse of phrases like the already mentioned ‘nanny state’ and ‘red tape’, used tendentiously to make political-ideological points (hence my use of scare quotes!).

Hutton, in contrast, is a champion of interventionist government and FDR’s New Deal is his inspiration: “The ambition, energy and experimentation of these reforms is impressive even after nearly a century.” Government, he believes, has an essential role to play in establishing “guiderails” for capitalism, acting as a catalyst for growth, renewing our democracy and protecting social cohesion.

Hutton is not a socialist. His goal is to radically rethink British capitalism to exploit its dynamism and ensure that it works more effectively. He quotes Evan Durbin, a largely forgotten academic and Labour politician of the 30s and 40s who once referred to himself as a “militant Moderate”, approvingly: “Expansion is the great virtue of capitalism; inequality and insecurity are its great vices.”

We need, says Hutton, to fuse Britain’s two progressive traditions (most closely associated with the Liberal Party and the Labour Party), and he refers repeatedly to the ‘I’ and the ‘We’, representing individual agency and fellowship respectively. Dynamic capitalism, he argues, needs to be “married to a belief in social cohesion, a sense of fairness and personal freedom, and structures that compensate for the sheer bad luck of life’s vicissitudes”.

It is the sheer scale of Hutton’s ambition, together with his conviction that it is achievable, that makes This Time No Mistakes such an exhilarating and compelling read. Take, for example, chapter nine – Changing Gear – which makes the case for a massive public investment programme (which, the theory goes, will then ‘crowd in’ private investment) to drive productivity and therefore growth. Or his twelve-point programme – set out in chapter thirteen – to repair our democracy and systems of governance.

I could go on. The second half of This Time No Mistakes fizzes with imaginative and often radical ideas, all geared towards achieving one goal:

There is a brighter future ahead. But to reach it, we cannot live with yet more years of disastrous or even timidly reformist policies … We can pioneer a twenty-first century civilisation in which everyone flourishes. It is more than possible, as this book will show. We just have to want it enough.

The final paragraph of the first chapter of This Time No Mistakes

Alas, Hutton’s vision – outlined with such brio – comes with a gargantuan slice of wishful thinking, predicated as it is on the willingness of Britain’s progressive parties to work together. The sad reality is that the very thing he abhors – a fragmented centre and centre-left – is the default setting for British politics, as the current election campaign has once again demonstrated. It is unlikely to change any time soon.

Hutton points out that the first-past-the-post (FPTP) voting system discourages compromise and collaboration and encourages division and polarisation, and he rightly calls for the replacement of FPTP with a more proportional system.

The Conservatives, he reminds us, have been in government for most of the last hundred years in large part because the progressive vote has been split between Labour and the Liberals. Hutton labels the failure to introduce a fairer voting system in 1918, when the Representation of the People Act massively increased the electorate (including extending the vote to many women for the first time), “the miscalculation of the century”.

More fundamentally, I would add, FPTP deepens Britain’s disastrous democratic deficit by effectively disenfranchising millions of voters who live in so-called ‘safe seats’ that rarely, if ever, change hands. It also results in a House of Commons the political complexion of which is often wildly at odds with what the electorate voted for. In both 1951 and (February) 1974, for example, the party that won the popular vote did not even end up with the largest number of seats in the House of Commons.

(The electoral-college system for electing a president in the USA is even worse. An election with more than 150 million eligible voters is nowadays decided by a few thousand votes either way in just a handful of the fifty states.)

But just as Tony Blair ended his flirtation with electoral reform as soon as he won a landslide in 1997, so the incoming Labour government will surely give it a wide berth now. With the current splintering of the right-wing vote, it will be fascinating to see whether the Conservative Party begins to show any interest. The (right-wing) Daily Telegraph columnist Tim Stanley has already toyed with the case for change. Unsurprisingly, Nigel Farage’s Reform UK, like all the smaller parties, already supports electoral reform.

So what chance is there of the new government achieving the transformation of Britain that Hutton – and many of us – so desperately yearns for?

The odds are stacked heavily against it. Nevertheless, I will end on a hopeful note by quoting Hutton’s post on X (formerly Twitter) on Thursday 13 June, the day of the launch of the Labour manifesto:

The Labour manifesto in its unassuming, unsung but purposeful way is as radical and potentially more enduringly transformative than Labour’s in 1945. Everyone under-rated Attlee, his ambition and capacity to bring it off. They are doing the same with Starmer.

Posted by Will Hutton on X (formerly Twitter) on 13 June 2024

Fingers crossed.