Books, TV and Films, January 2022

4 January

Back to the wonderful world of historical fiction to welcome in the new year. I discovered Andrew Taylor last summer. His The Last Protector, set in Restoration England, is from his Marwood and Lovett series (I also now have The Ashes of London, the first of them). Hilary Mantel’s The Mirror and the Light, the final part of her Thomas Cromwell trilogy, still awaits, and her 800-page A Place of Greater Safety, set during the French Revolution, is also on this year’s reading list. The wonderful Kate Mosse also has her latest paperback out later this month, I think, the sequel to The Burning Chambers.

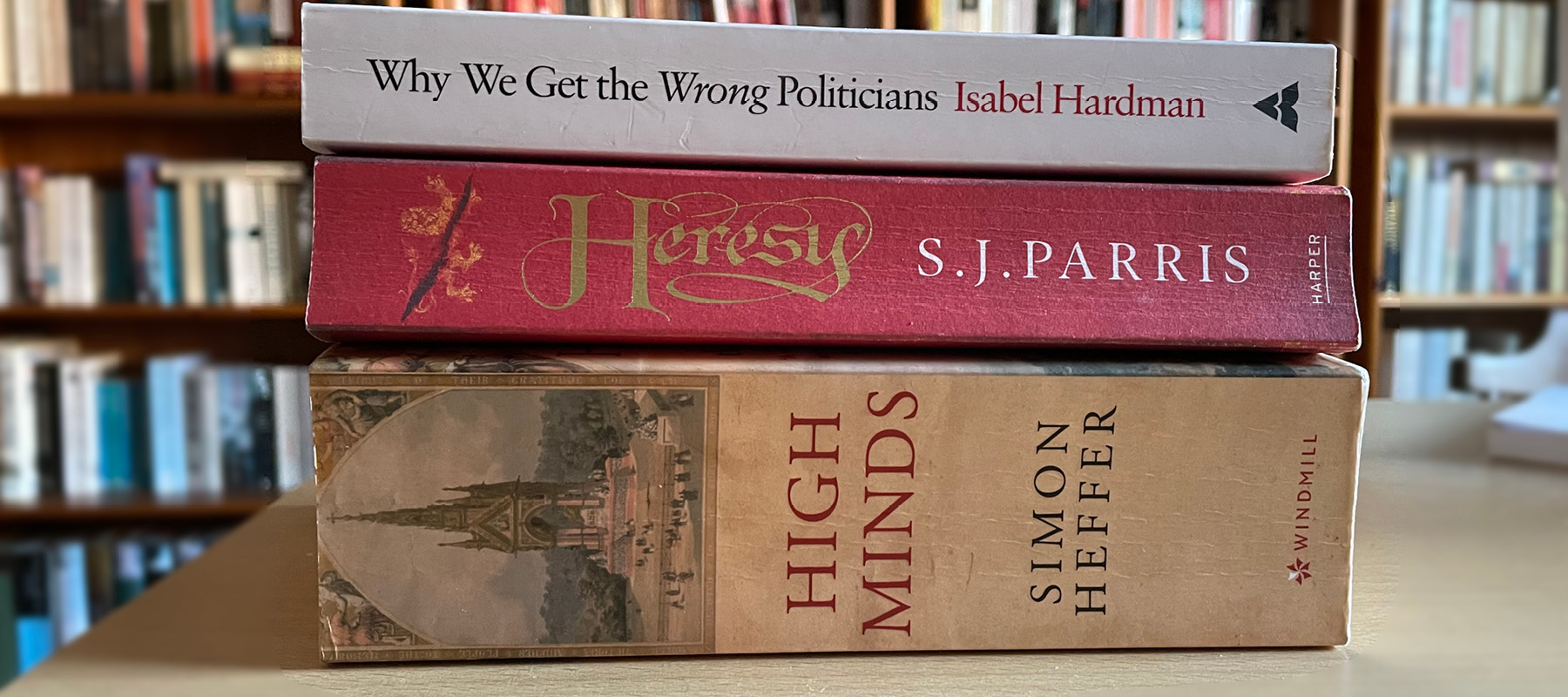

I keep mixing up SJ Parris and CJ Sansom. Similar names, similar covers, similar titles. I have already read Sacrilege by Parris but, as usual, I wanted to start at the beginning. Hence Heresy, the first in the Giordano Bruno series, set in Elizabethan England.

The prologue (the origin story of sorts) is actually set not in England but in Naples at the Monastery of San Domenico Maggiore. We meet Bruno in the privy, caught not quite with his pants down reading a copy of Erasmus’ Commentaries, which was on the Catholic Church’s Index of Forbidden Books. He escapes just ahead of the arrival of the Father Inquisitor, whose verdict would not have been in any doubt. Seven years later, and now in England, Bruno is taken on by Sir Francis Walsingham as one of his vast network of spies working on behalf of the Elizabethan state.

Heresy has everything you would want and expect from great thriller writing: mystery, deceit, treachery — all set against a backdrop of the internecine religious struggles of the time. In short, the twists and turns are suitably tortuous, the pace utterly relentless and the thrills page-turningly thrilling. I read the second half of the book in a single day.

Any body of ideas — whether we’re talking religious beliefs, philosophical outlooks, economic theories or political ideologies, is likely to contain different strands and strains, quirks and nuances, practices and rituals. I was struck by the thought that Parris’ description of a secret mass at the dead of night could just as easily have come from the pages of a Dennis Wheatley black magic novel:

I found myself in a small room crowded with hooded figures who stood expectantly, heads bowed, all facing towards a makeshift altar at one end, where three wax candles burned cleanly in tall wrought silver holders before a dark wooden crucifix bearing a silver figure of Christ crucified.

from Heresy by SJ Parris

6 January

Four Lives was much-watch TV, the ‘based on a true story’ account of the murder of four young men by Stephen Port between June 2014 and September 2015. In each case Port administered fatal doses of the so-called ‘date rape’ drug GHB and dumped his victims’ bodies near his flat in Barking.

This wasn’t sensationalist or prurient TV. The focus was not on the actual murders or even on Port himself, but on the family and friends of each of the victims and the devastating impact the murders had on them. Sheridan Smith was excellent as the mother of the first victim, Anthony Walgate. Stephen Merchant was also terrific as Port. We are used to Merchant using his unusual physique for comic effect. Here he uses it to project utter creepiness. When Port removed his wig, I was immediately reminded of Richard Attenborough as John Christie in 10 Rillington Place.

Sadly, tragedies like this happen all too often. What sets the Port murders apart, however, are the actions and behaviour of the police. The response of the family liaison officer to a mother frustrated by the lack of progress or even of information — along the lines of ‘This is my first case, but I have done the training’ — might initially strike the viewer as bad writing until you realise that the police’s catalogue of cock-ups really is jaw-dropping. An inquest jury found just last month that fundamental failings by the Met “probably” contributed to three of the four deaths.

7 January

So sad to hear of the death of Sidney Poitier. Two of his films had a massive influence on me, growing up. In the Heat of the Night was probably the first film I ever saw that dealt with racism. And To Sir, with Love remains in my top 5 all-time favourites. The theme song (sung by Lulu, of course, who was in the film) is wonderful. A number one in the USA, but only a b-side in this country. Unbelievable!

8 January

On the subject of cock-ups, a book that I am surprised doesn’t get more mentions is The Blunders of Our Governments by the political scientists Anthony King and Ivor Crewe, who once upon a time were regulars on late-night by-election specials on TV. Published in 2013, it took a close-up look at some of the governmental howlers of modern times and at the flaws and failings of our political system which allow such gargantuan errors to occur.

I am not sure what I was expecting before I read Why We Get the Wrong Politicians by Isabel Hardman — a right-wing, populist-flavoured hatchet job on our MPs, perhaps (Hardman writes for the Spectator). I was agreeably surprised, then, that it was clear before I had even finished the preface that Hardman believes that the vast majority of MPs, of all political parties, are not selfish, venal or lazy, and milking the system for their own benefit. Most of them — she and I agree — are there for the right reasons: they work hard and want to improve their constituents’ lives. It is the political system that is flawed. This is a book about structures and culture: it is those that urgently need to be reformed.

The book opens with a couple of chapters on the eye-watering costs — both personal and financial — of even becoming an MP. Who on earth, I ask myself, would want to bother? Most of the book then focuses on what happens within parliament and government. There are just so many things that need to be modernised, that leave the whole process open to ridicule, or that are just plain wrong.

Here are just a few: the fact that an MP following their principles when it entails defying the party whip is potential career suicide; the fact that ministers are reshuffled so often that they have little chance of really getting to grips with the issues before they are moved on (eight housing ministers in nine years is a statistic I have seen more than once); the fact that it’s often the ‘noisy’ ministers — not the talented ones — who get promoted.

Most eye-opening for me was Hardman’s description of the committee stage of a bill. In theory, it is the part of the law-making process where political partisanship takes second place to a disinterested line-by-line consideration of the bill on its merits. In reality, says Hardman, members of the committee are chosen by the whips and it is well known as “an opportunity to write Christmas cards while paying little heed to the arguments being presented”.

The fundamental problem — the key structural issue not just with parliament but with democracy itself — is, as she says, that politicians have to be both “policy fixers and political winners”. Those two aims are often in conflict — as the politics of climate change reveals all too clearly. How likely are politicians to introduce policies that will cause significant upheaval to people’s lives and involve raising taxes when the benefits will only be felt in the medium term — and in fact may only be noticeable by their absence? Put it another way: was the widely predicted meltdown that would result from the millennium bug avoided because of timely pre-emptive action or was the threat it posed massively overhyped?

Hardman is particularly good on the political sleight-of-hand that occurs when politicians claim to be ‘taking the politics out’ of an issue — in reality, avoiding something that will upset a significant tranche of voters and thereby abdicating responsibility, often by passing it to a commission of enquiry of some sort.

She ends with a couple of suggestions for change, the best of which involves a beefed-up role for select committees. Alas, changing a deeply rooted culture is far easier said than done. I remember the talk in the Commons after the death of John Smith in 1994 of how we needed to take the bile and bitterness out of political discourse. It didn’t last. It never does. Just look at the political headlines over the last few weeks. When our current prime minister offered an apology to the House of Commons recently, he couldn’t even do humility for ten minutes before throwing a pathetic slur about the failure to prosecute Jimmy Savile across the despatch box.

11 January

Having discovered Nicola Walker in Spooks and been totally wowed by her in Unforgotten, I made a point of recording Annika, a crime drama shown recently on the cable channel Alibi. She plays a detective inspector, busy negotiating the ups and downs of personal and professional relationships after taking up a new post. Walker is fab, using the excellent breaking-the-fourth-wall script (you can tell it started life on radio) to make the most of her quirky but sharp character. Annika also takes top prize for — especially in these days of endless cutbacks, reorganisations and amalgamations — most unlikely police unit: the Glasgow Marine Homicide Unit.

14 January

I used enforced Covid isolation over the new year to re-watch all the Harry Potter films. I had forgotten how good they are — too long, but good. The (then) child actors were exceptionally well chosen. In the first film, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, they are believable; by the third in the series, now probably mid-teens, they are very good.

28 January

Marc Morris tells us in his book The Anglo-Saxons that the response of King Æthelred to renewed Viking attacks on England in the early eleventh century was to issue an edict requiring all his subjects to participate in a national act of penance, including fasting for three days and processing barefoot to church accompanied by priests carrying holy relics.

To modern ears it doesn’t sound like much of a defence strategy. As hard as I try, I find it difficult to grasp how the world must have appeared to the medieval mind: in thrall to a God who was clearly not just omniscient and omnipotent but also vain and vindictive, uncaring and judgemental.

If the stranglehold of religion on the popular imagination was not quite so total by the mid nineteenth century, it still exerted a powerful grip on some of the finest minds and elite institutions — not least the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, where academic advancement was shut off to anyone but card-carrying members of the Church of England. Theological disputes that seem (to me, anyway) obscure and esoteric derailed many a promising career.

At least that’s the impression I get from reading the opening chapters of High Minds: The Victorians and the Birth of Modern Britain, Simon Heffer’s account of the social, cultural and intellectual life of Britain between c1840 and c1880. Elsewhere, it’s like listening to an episode of Radio 4’s The Long View, the programme that looks at stories from the past in the light of current events.

He tells the story, for example, of the preparations for the Great Exhibition of 1851, reminding me not so much of the Queen’s upcoming platinum jubilee (details of which have just been announced) as the origins and development of the Millennium Dome project, which I assume will feature prominently in Volume II of the Alastair Campbell Diaries.

The Great Exhibition and the Albert Memorial projects between them take up nearly 100 pages. High Minds is a big, weighty and demanding book, not helped by the fact that Heffer includes far too much extraneous detail, not least about the course of parliamentary debates: back then individual speeches often lasted for hours and debates for days.

The chapter on the ‘heroic mind’, for example, makes interesting points about a Victorian cult of the dead and about architectural tastes, but these struggle to breathe, suffocated by all the detail about the tortuous negotiations concerning the proposed Albert Memorial. Heffer frequently quotes at length, a practice not helped by the fact that the Victorians favoured an exhausting and sometimes baffling let’s-use-fifteen-words-where-five-will-do style in both speech and writing.

A recent letter in the Guardian objected to the use of the soubriquet ‘Member for the Eighteenth Century’ to describe the government minister Jacob Rees-Mogg, on the grounds that the eighteenth century was an age of enlightenment, “with a long list of luminaries whose names have become bywords for the possibilities of the thinking and endeavour of which humans are capable”. As Heffer shows, the nineteenth century was similarly full of ‘high minds’.

Equally, however, it was a time of the most appalling snobbery, bigotry and downright cruelty. Take Stafford Northcote, for example, a man whose name is forever associated with groundbreaking and far-sighted reform of the civil service. He said this about the Irish potato famine (the relief efforts for which he was involved in):

…[a] mechanism for reducing surplus population … the judgement of God sent the calamity to teach the Irish a lesson, that calamity must not be too much mitigated … The real evil with which we have to contend is not the physical evil of the Famine, but the moral evil of the selfish, perverse and turbulent character of the people.

quoted from High Minds: The Victorians and the Birth of Modern Britain by Simon Heffer (p472)

And, as with Peter Ackroyd’s description of Winston Churchill, it is impossible to read Heffer’s description of Benjamin Disraeli and not imagine that he had the current prime minister in mind when he wrote it. It is telling that, in his evaluations of the two titans Gladstone and Disraeli, the arch Conservative Heffer is so full of admiration for the former (a liberal) and so scathing about the latter.

Here’s a flavour from page 269:

The two men exemplify the Victorian political mind at its best and worst: Gladstone the man of principle, even if he had to engage in occasional contortions to try to remain principled; and Disraeli the opportunist, craving power for its own sake and not because of any great strategy to transform Britain and … willing to throw away any principle in order to stay in office.

quoted from High Minds: The Victorians and the Birth of Modern Britain by Simon Heffer