Books, TV and Films, April 2021

3 April

I avoid opening Amazon’s emails telling me what their omniscient algorithms think I should be buying and I never even look at the latest fiction and non-fiction charts so, other than skimming the Guardian’s Review magazine on Saturdays, I am always rather in the dark about new book releases. Now that bookshops are open again — well, they will be in a few days — it’s an opportunity to start paying more attention to new writing in history, biography and politics. (Though I remain loath to buy books about the contemporary political scene, which almost by definition date very quickly, I will probably make an exception for Peter Oborne’s The Assault on Truth, a favourite topic of mine these days.)

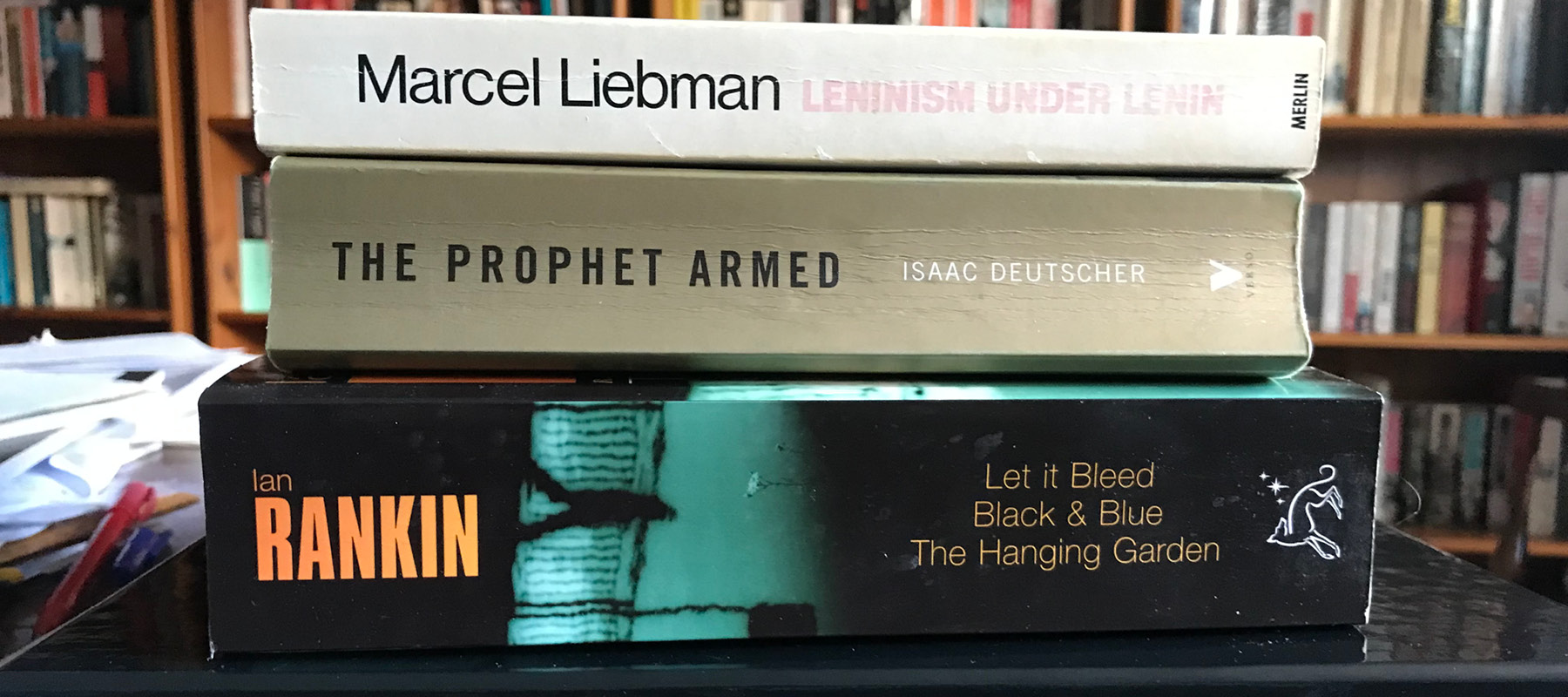

More than ever this last year I have been drawn back to old favourites — books that first made an impression on me years ago, or that have outstanding literary merit, or that are recognised as classics. High up on that list is the three-volume biography of Leon Trotsky by Isaac Deutscher. Volume I is called The Prophet Armed and covers the years up to 1921.

Deutscher is widely recognised as one of the outstanding Marxists of the time (he was active from the late-1920s until his death in 1967) — a highly influential activist, historian and journalist. The Prophet Armed is beautifully written. Though its scholarship will now of course be superseded, at the time (it was published in 1954) it made extensive use of previously unavailable material. And, although Deutscher is very much associated with the Trotskyist wing of world communism, his biography is by no means hagiographic, paying due attention to Trotsky’s flaws, mistakes and misjudgements.

Trotsky has always struck me as — even more than Lenin — the towering figure of the Russian Revolution. He was a more charismatic leader than Lenin, a more engaging public speaker, a more gifted writer and to my mind (though this is certainly arguable) a more daring strategist and effective organiser and administrator, certainly in the period from 1917 to 1921. It was Trotsky who was at the centre of events in 1905, as chair of the Petrograd Soviet. It was Trotsky who masterminded the seizure of power in October 1917. And it was Trotsky who created the Red Army from virtually nothing and ‘saved’ the revolution from defeat in the ensuing civil war.

Much writing about the Russian Revolution itself — perhaps most notably in recent years the work of Robert Service, formerly professor of Russian history at the University of Oxford — comes from historians whose work is influenced by their hostility to communism, perhaps involving the conviction that the later horrors of Stalinism and the broader failings of the Soviet state were/are an intrinsic part of the communist package, or who assume that the revolutionaries were all along motivated largely by cynical, violent and base urges. The sympathetic pen of Deutscher, on the other hand, reminds the reader of what the revolutionaries themselves believed they were fighting for — the introduction of true equality between all peoples and the flourishing of genuine freedom and democracy through the eradication of all forms of exploitation.

All of which gives the closing chapter of Volume I in particular —entitled Defeat in Victory — the air of Greek tragedy: the opponents of imperialist war waging aggressive war against Poland; the emancipators of working people introducing forced militarisation of labour and the widespread use of terror; the proponents of true democracy instituting a one-party state, banning dissent even within the Communist Party itself and crushing rebellion at the previously loyal Kronstadt naval base.

5 April

Not being a telly addict I have missed out on a huge amount of quality television over the years. Take your pick from the last thirty-five years – Our Friends Up North, 24, The Sopranos, Breaking Bad: a mouth-watering smorgasbord of highly acclaimed drama and I haven’t seen any of them.

Part of the problem is that by the time a programme becomes a bleep on my radar, it’s already too late: the series is underway, plots and characters are established, threads are busily interweaving and knotting. Okay, I am exaggerating. DVD box sets have been around for ever (though it’s an expensive mistake if a programme turns out to be a turn-off rather than a turn-on) and cable/satellite TV, catch-up TV and TV on demand mean that, unlike in the old days, I can make the effort if I really want to. Plenty of ‘classics’ repeated from the very beginning. Take The Eagle’s Nest, for example, the first ever episode of The New Avengers from 1976, which I watched (again) recently. Who can resist a Hitler-didn’t-really-die-in Berlin-in-1945 plotline?

To quote The West Wing’s Sam Seaborn, let’s ignore the fact that I arrived at the party late and celebrate the fact that I have turned up at all. I first watched both Friends and The Office about a decade after they initially aired. The ten series of Spooks filled much of the first lockdown, and I have watched all bar the first series of Unforgotten during the current one.

Which brings us to Line of Duty. Mother of God, it’s good. There’s the (admittedly rather daft) ‘Who is H?’ story arc, the Arnott–Fleming partnership (though the serious overuse of ‘mate’ is starting to grate) and then there are the Ted-isms. Now we’re sucking diesel.

Best of all are the set-piece extended grillings in the interview room: the cat and mouse, the shifts in the power balance, the perfectly cued-up evidence, the beautifully timed interjections — all apparently with no pre-interview preparation time from AC–12’s finest. Wonderfully executed dramatic licence. No doubt the reality is far less slick; try listening to any of the US president’s press secretaries (even the articulate ones) after watching a CJ Cregg monologue in The West Wing (again).

12 April

From Line of Duty and Unforgotten back to detective fiction; this time John Rebus rather than another Poirot. I first started collecting Rebus after noticing that they are a charity shop staple. My intention was/is to read them in chronological order. The first Rebus novel (written by Ian Rankin) was Knots and Crosses, published in 1987. I am up to the seventh in the series, 1996’s Let It Bleed.

I have a memory of Rankin saying that it was with this novel — or perhaps it was the next one, Black and Blue, which is considerably longer — that he felt that his writing really improved. There is a definite sense here of the two things for which the Rebus novels are perhaps best known: the city of Edinburgh itself, and the many backstreet dives that Rebus frequents — and loses himself in — both socially and professionally. The title, a reference to a Rolling Stones album (Rebus is a big fan), describes both the malfunctioning heating in Rebus’ flat and a painful gum abscess. It also serves as a metaphor for the corruption among Edinburgh’s elite that Rebus is investigating.

Let It Bleed is certainly an enjoyable read, excellently plotted and structured. One thing that slightly puzzles me about Rankin’s writing is that it is sometimes difficult to disentangle the narrator’s voice, which is infused with humour, irony and sarcasm, from that of Rebus himself. A couple of examples. The DCI has been seriously injured and the station talk is all about who will step into his shoes: “The rumours piled up faster than the collection money”. Then there’s a photo of a kidnapped girl “which somehow the media got their paws on”.

18 April

Don’t be fooled into thinking that McDonald & Dodds, one of ITV’s more recent detective dramas, is set in the city of Bath. The real location is the same alternate universe (© American Sci-Fi) as Midsomer Murders, where the sky is perpetually blue, the rolling countryside is liberally splashed with bright greens and yellows, and life rolls along at a sedate, self-satisfied pace. Swearing, litter and graffiti don’t exist. Even the mass murderers are considerate enough not to upset the idyll with anything as vulgar as a gore-splattered crime scene. The viewer is left wondering whether a body that has been hacked to pieces even bleeds.

The writers have managed to conjure up one more permutation of the ‘mismatched partners’ trope — this time it’s a dull, plodding but really quite sharp old hand (think Inspector Columbo) paired with an ambitious, brash but likeable woman of colour from the Big City. It’s all good cartoonish fun, an enjoyable antidote to the darkness typical of most crime drama. Chief Superintendent Houseman, however, is a caricature too far. Imagine a younger and (much) slimmer version of Chief Superintendent Strange from Inspector Morse. This comment (to DCI McDonald) made me laugh though: “You tick boxes that haven’t been invented yet.”

30 April

The odd thing about reading Leninism Under Lenin by Marcel Liebman (another thinker who, like Isaac Deutscher, was sympathetic to the Bolsheviks but not blind to their mistakes and failings) is that I was less clear in my understanding of how to define Leninism at the end of the book that I was before I began it. That’s not a fault of the book — for a work focusing as much on political theory as on actual historical events it is admirably clear and accessibly written.

I might previously have said that Lenin’s main contribution to the development of Marxism was the idea of a tightly knit group of professional revolutionaries held together by iron discipline. Yet Liebman shows that — both during the long years of Lenin’s exile before 1917 and even more so in the first years after the revolution — Lenin was regularly outvoted and his views opposed or ignored by various factions within the party (and I don’t mean the Mensheviks).

Or I might have said that the idea of the party as the elite vanguard of the working class, its historic role being to develop the revolutionary consciousness of the broad mass of workers who thought only in terms of economic wants, was the essence of Leninism. Yet the revolutions of both 1905 and February 1917 were essentially spontaneous uprisings, the Bolsheviks failing on both occasions to predict, still less to lead and direct, the flow of events — in the Bolsheviks’ own terms, the masses were ahead of the party in their consciousness.

At other times, however, the idea of the party acting in what it claimed was the objective interest of the workers — regardless of what the workers themselves wanted or believed at a particular moment — left the Bolsheviks open to accusations of ‘substitutism’, a charge levelled not least by Trotsky before he joined the party on the eve of the revolution. By 1921 (say) this charge carried real force and brought into question the legitimacy of the entire regime: with the collapse of industry and after years of civil war there hardly was a working class left in Russia and yet the Soviet government justified its single-party rule and its extreme measures in the name of the dictatorship of the proletariat.