Books, TV and Films, July 2021

1 July

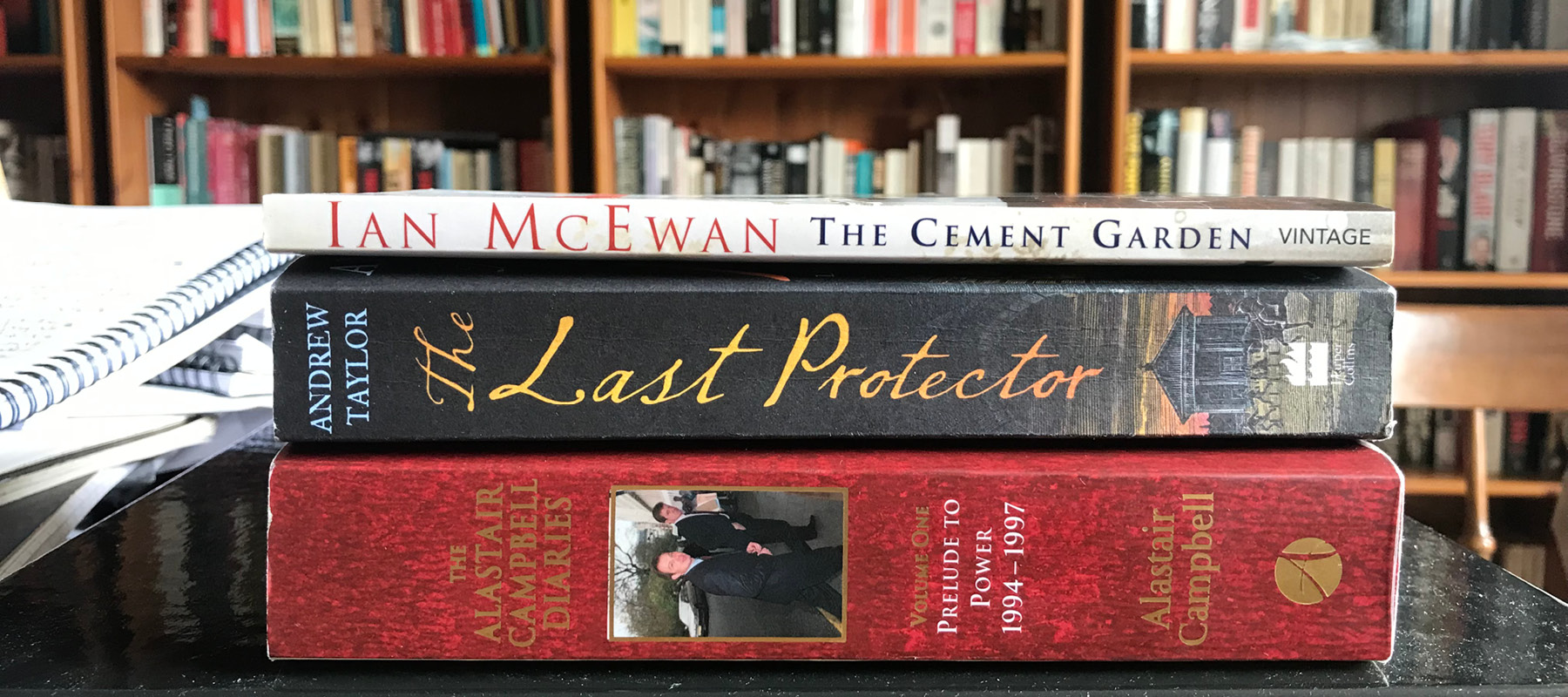

The Cement Garden was Ian McEwan’s first novel (well, novella; my copy is just 138 pages), published in 1978, though he had previously released some short stories. The story of four children who lose first their father and then their mother within a year or so following a debilitating illness, it is a blend of, on the one hand, the mundane and the ordinary and, on the other, the absolutely extraordinary, principally the concealing from the authorities of their mother’s death by encasing the body in cement in the cellar.

The story has something of Lord of the Flies about it as, free from all adult supervision and control, the children regress to an almost primitive state of existence, for example neglecting essential housework and the needs of the youngest child. Meanwhile, the two ‘grown-ups’, Julie and Jack, are discovering their sexuality. Julie, 17, is seeing her first boyfriend — a snooker player in his 20s — who lavishes gifts on her, though she refuses to have sex with him. Jack, meanwhile, an obsessive masturbator, (literally) comes to sexual maturity during the timeframe of the book. McEwan early on captures the sense of adolescent curiosity and sexual awakening: during a game of ‘doctors and nurses’ involving younger sister Sue, “Julie and I [Jack] looked at each other knowingly, knowing nothing.”

5 July

With reference to Hilary Mantel I wrote back in January: “Historical fiction — the well-written variety — can be a friend to the uninitiated, an entrée into worlds only dimly understood. As well as requiring encyclopaedic knowledge and command of the sources, the writing of historical fiction takes a different approach to that of the historian or biographer and requires a different skill set. There is, for example, no room for ‘possibly’, ‘probably’, ‘maybe’, ‘on balance’. It is, in part at least, history of the imagination.”

Hilary Mantel’s trilogy audaciously recreates the life and times of Thomas Cromwell. Most historical fiction is of course much less closely aligned with real people and real events, perhaps using a time and a place, an individual or an event as the starting-point for a story, the author using their knowledge and skills to interweave fact and fiction in order to create something plausible and convincing. I enjoyed the SJ Parris novel Sacrilege, set in the time of Elizabeth I, and quickly realised that I had landed in the middle of a series about a free-thinking and adventurous Italian philosopher, Giordano Bruno.

I have done the same with The Last Protector by Andrew Taylor. It is perfectly readable as a standalone novel, but is also apparently the fourth in the Marwood and Lovett series set in the London of the mid-1660s — a time of plague, the Great Fire and (in this novel set in 1668) plots against the Crown. Taylor is an excellent guide to the England of Charles II, with impressive knowledge of Restoration London. He brings out superbly the etiquette, codes and manners, the rigid social hierarchies and the contradictions of the age — particularly the fabulous wealth juxtaposed with gut-wrenching poverty, and the public displays of morality, decency and civility so often masking disreputable and hypocritical private behaviour.

6 July

The actor Stuart Damon has died. He made his name in the ’60s, starring in The Champions alongside William Gaunt and Alexandra Bastedo. The series made a lasting impression on me: one of my earliest memories is of wanting to play/pretend at being The Champions, so I am guessing I watched reruns in the early ’70s.

The Champions either fed on or began a childhood interest in shows featuring people with secret superpowers or extraordinary skills — programmes like The Invisible Man starring David McCallum and later on Kung Fu with David Carradine as Kwai Chang Caine. Even something like Alias Smith and Jones. I was fascinated with Thaddeus Jones/Kid Curry, the reluctant gunman who was nevertheless lightning-quick on the draw. Above all, there was The Six Million Dollar Man and then the spin-off, The Bionic Woman.

As a child, I found series like these much more exciting than, say, The Avengers or The Saint; for all their ingenuity, the likes of Steed and Simon Templar were, after all, mere mortals with no particularly outstanding skills or powers. It was only when I was a bit older that I started to appreciate the style, wit and sheer quirkiness of (first) The New Avengers and then The Avengers.

28 July

I have long been a fan of political diaries, ever since I used to stare at a multi-volume set of the Crossman diaries in the room of one of my politics tutors at university. I bought the complete set of the Tony Benn diaries as and when they came out, starting with Out of the Wilderness 1963–1967 (published in 1987). The lengthy descriptions of Cabinet discussions in the Labour governments of the ’70s are riveting. The diaries of Gyles Brandreth, published as Breaking the Code and covering his time as a Conservative MP in the ’90s, including a spell as a government whip, are also excellent, well written, as you would expect from Gyles, but also insightful and revelatory. I have also read some of the Chris Mullin and the Alan Clark diaries.

The diaries of Alastair Campbell, however, surpass them all. I read the extracts published as The Blair Years after he left government service in 2003. Good as they were they omitted much of the nitty gritty of the tense relationship between Blair and Brown, both then still in power, of course. I have decided to read the full, unexpurgated diaries (eight volumes so far, the most recent covering the period from 2010 to 2015).

Campbell is a workaholic. Despite a punishing work schedule he somehow found time to write or dictate lengthy diary entries at some point during the day. The writing inevitably has something of an of-the-moment feel to it. References are not always explained or contextualised, multiple topics are often covered in the same (long) paragraph and the use of indirect speech (‘he said/she said’) sometimes makes sentences hard to follow, as in this example:

I saw Andy Marr and raised what GB [Gordon Brown] had said. He said he had said no such thing. He said the only time the Leader’s Office was raised in any discussions was from Ed Balls saying I had pulled the wool over their eyes in convincing them CW [Charlie Whelan] was behind all these stories.

Prelude to Power 1994–1997, Alastair Campbell, 12 March 1997

Volume One, Prelude to Power 1994–1997, begins with the death of John Smith in May 1994 and ends with the election campaign of 1997. It is an extraordinary read — frank, detailed and remarkably honest. Very little seems to be off-limits. For example, Campbell is completely open about the impact that working for Blair had on his home and family life.

The diaries totally disprove the idea that as the dysfunctional Major government imploded during the mid-’90s New Labour was a well-oiled machine preparing for power. Campbell shows that in reality the Labour Opposition was equally dysfunctional: blazing rows, extraordinary displays of petulance and perpetual in-fighting. These random extracts are entirely typical.

Back at the House I went up to see him [Prescott] because he was so offside and we ended up having a furious row. He said he was excluded from anything and he was just going to walk away from it all … I said who is going to be helped by that? He was by the door by now, and he walked back towards me, looking very hurt and angry, and for a second I thought he was going to get violent. But he stopped short, looked at me, and there was just a sadness across his eyes and his face.

Prelude to Power 1994–1997, Alastair Campbell, 2 February 1996

Peter [Mandelson] came back later [after a row with Brown] … and TB [Tony Blair] said “You cannot talk to Gordon like that in a room full of people,” and Peter said in that case he was happy to quit doing the job that TB had given him. “I have had enough. I am not going to put up with it any longer, being undermined by GB and getting no support from here.” He picked up his jacket, walked out again and slammed the door even louder than before. I looked at TB and he looked at me, and we both stood there shaking heads. TB sat down and said “What am I supposed to do with these fucking people? It’s impossible.”

Prelude to Power 1994–1997, Alastair Campbell, 9 May 1996

Campbell pulls no punches. His judgements are frank, unvarnished and often brutal. One wonders how the likes of Chris Smith, Harriet Harman and Clare Short must have felt, reading about themselves as not up to the job (Smith, p439), soporific (Harman, p654) or “a fucking nightmare. Never was so much effort required to deal with someone so useless” (Short, p503). It’s no wonder that when a new volume comes out public figures are said to turn to the index first to see what Campbell has written about them.

And for all his admiration for Tony Blair, Campbell is equally withering at times about (among other things) Blair’s mood swings, his self-obsession and lack of consideration for his staff, and his inability to deal with all the infighting.

And then this comment, from the ’97 election campaign, made me laugh out loud:

I left to see the liveried buses down at the depot where the work had been done. They were good, though not quite as spectacular as I had been hoping for. Maybe there is only so much you can do with the side of a bus.

Prelude to Power 1994–1997, Alastair Campbell, 27 March 1997

29 July

Redemption Day, a 2021 film starring Gary Dourdan — brave soldier suffers trauma in battle, struggles with mental health in civilian life, wife is kidnapped by terrorists in Algeria, flies over, kills the bad guys, rescues her, politicians and CIA agents are corrupt. The same old same old. Just awful. The scene involving being tailed by a car is just comically bad. Why do I watch this drivel?! Hit the Delete button, man!