Books, TV and Films, October 2020

1 October

The Romantics and Us is the latest TV series from Simon Schama, who is perhaps best known to non-historians for his A History of Britain TV series at the turn of the millennium. Watching this is part of ongoing efforts to broaden my cultural awareness. Art is one of many weak spots.

Schama himself is fascinating. He is a frequent interviewee on news and current affairs programmes like BBC’s Question Time. Unlike Peter Hennessy, who I mentioned last month in the same context, I find him frustrating to listen to in open discussion — the ‘umms’ and ‘errs’ and unpolished sentences matching his sometimes awkward physical jerkiness as he tries to articulate his thoughts. I find him much more watchable when he is working to one of his own scripts. One of his specialisms is art history; he fizzes with enthusiasm and radiates authority (assuming you can fizz and radiate at the same time).

He is also an absolute joy to read. I finally tackled Citizens, his huge and rather unorthodox history of the French Revolution, last year. And I will never forget his essay on the front page of The Guardian after 9/11, powerful and moving. It is included in a book of his collected writings called Scribble, Scribble, Scribble. Odd how memory plays tricks. I was sure it was the front-page lead in the newspaper the very next day, but the book dates it to 14 September.

2 October

Not quite uncharted territory but my latest read sets me on a journey I don’t normally undertake. My destination is the world pre-1600, specifically the Tudor court of Henry VII. Winter King by Thomas Penn comes highly recommended, judging by the cover quotes and the prestigious awards it has garnered.

As a proofreader, my antennae are attuned to these things, I suppose, but I was immediately intrigued by the style rules the book follows. A basic rule followed by most style guides is that jobs and roles are lower case and titles are upper case. I agonise over the distinction sometimes and, judging by proofreaders’ blogs, nothing seems to infuriate people more than seeing their prestigious role in a company rendered in lower case, as if it is an egregious attack on their dignity or a personal slight. Take the time to look when you are reading your ‘quality’ newspaper (maybe not the Telegraph, though) or trawling a respected news website like the BBC’s, and you will indeed see ‘the president’, ‘the prime minister’, ‘the chief executive of …’ and so on.

Anyway, a sentence from Winter King (page 85 of the paperback, opened at random):

The entourage, which included Garter king-at-arms John Writhe and a number of prominent nobles, was headed by Thomas Howard, earl of Surrey.

4 October

I watched both episodes of Honour last night. Terrific, not least Keeley Hawes as DI Caroline Goode. I know Hawes from Ashes to Ashes (for which she drew a lot of unfair criticism initially, the series being compared unfavourably to Life on Mars) and more recently from my Spooks lockdown binge-watch (she appeared in the first couple of series or so).

Honour tackled the subject of so-called honour killing via the real-life case of Banaz Mahmod, a young Iraqi Kurdish woman from London who was murdered on the orders of members of her family because she ended an abusive forced marriage and started a relationship with someone of her own choosing.

The drama has received some criticism because its focus was the police investigation and not the murder victim herself. Be that as it may, I found it compelling, moving and terribly sad, not least the failure of the police to protect Banaz Mahmod on at least four separate occasions before her actual murder occurred.

I found its depiction of the work of the police entirely believable — from the under-resourced computer analyst to the long hours of boring but essential investigative work. There was nothing remotely glamorous about this portrayal, a sense nicely reflected by Keeley Hawes as the down-to-earth and — dare I say — dowdy detective inspector in charge of the case. We are so used to scenes of senior officers using their rank to scold or belittle their junior colleagues — none more so, perhaps, than the curmudgeon-in-chief Inspector Morse — that it was also refreshing to see how well DI Goode worked with, and led, her team, who referred to her affectionately as ‘Smudge’. Off the top of my head, the only other fictional senior police officer I can think of who is unfailingly polite to junior officers is Columbo.

9 October

I recommended the original The Dead Zone film (ie not the later TV series, which I haven’t seen) to a friend and decided to watch it again myself. It’s a film I first watched at the cinema back in 1983. At the time (I was in the sixth form) I was a regular cinemagoer, influenced by a friend who was a huge film buff. It was the time when video shops were beginning to take off, so a huge selection of previously unavailable films was suddenly at my fingertips. My friend was heavily into cult directors like Brian de Palma and Nicholas Roeg. The Dead Zone was, I think, the first mainstream film of David Cronenberg, a cult horror director, who went on to do a remake of The Fly with Jeff Goldblum.

Watching it again, the film perhaps feels a little dated in places, particularly the ‘visions’ sequences. But what is most noticeable is how stripped back the storytelling is. Anyone familiar with the author Stephen King’s writing will know that he likes to take his time. It’s a hefty book and it meanders around (or so I thought when I read it, which was almost certainly only after having seen the film), with a much more prominent role assigned to the charismatic politician, Greg Stillson.

The film, by contrast, is very sharply focused: the accident, the visions, the rise of Stillson. Only the suicide of the homicidal police officer feels somewhat out of place, as if Cronenberg is clinging to his horror roots. The bathroom scene in which Officer Dodd opens his mouth wide before impaling himself on the open scissors — bringing to mind countless sci-fi and horror films in which an alien in human form finally reveals its true non-human appearance — is not quickly forgotten.

I found all the characters (and the actors’ performances) convincing — particularly Johnny’s long-suffering parents and the sympathetic doctor played by Herbert Lom. Christopher Walken is outstanding as the awkward misfit, his body slowly weakening as his visions become ever stronger. Martin Sheen has specialised over the years in playing charismatic politicians, of course, though a political figure less like President Josiah Bartlet (of The West Wing) than the malevolent Greg Stillson is hard to imagine. With his finger literally on the nuclear button, Stillson’s unhinged ravings in the film’s closing sequence make for uncomfortable viewing in the age of Trump.

10 October

I get frustrated at the build-up of unwatched films and other programmes in the ‘My Recordings’ folder of my TV box, and then I add to the problem by not only recording new things but also revisiting stuff I have already seen. Yesterday, The Dead Zone; today, Maigret Has a Plan, the pilot for the short-lived series of ITV Maigret dramas starring Rowan Atkinson.

I thoroughly enjoyed it first time round and was surprised to read some less than flattering reviews. The Guardian‘s TV critic called it “leaden”; I wrote back then that it was “dark and broody”. Far from regarding it as slow and ponderous, ‘giving itself time to breathe’ is precisely what I most enjoyed about it. Wasn’t this exactly what critics were applauding when Inspector Morse reinvented TV drama with its single-episode, two-hour dramas back in the eighties?

13 October

I finished Winter King earlier today. It is a terrific book, one that has definitely fired up my curiosity for reading more pre-1500 history, about which I know so little. Considering that he reigned for 24 years, Henry VII is almost the ignored Tudor. Time and again, the focus of books, documentaries and films seems to be Henry VIII or Elizabeth I, with Mary I close behind (and Edward VI the forgotten rather than the ignored Tudor). Thomas Penn shows us what a fascinating and controversial reign it was.

Two things resonated powerfully as I read the book. The first were the steps taken blatantly to rewrite history at the start of the new king’s reign in a bid to strengthen his extremely weak claim to the throne (he was the grandson of the Welshman Owen Tudor who had married Henry V’s widow). The aphorism ‘History is written by the victors’ is heard so often that it probably counts as a cliché, but the thing about clichés is that they usually contain at least a kernel of truth. Terms like ‘spin’ and ‘fake news’ are part of modern-day political vocabulary, but are they anything other than just new ways of describing patterns of behaviour that have always existed in the world of power politics?

The second was how the Crown rode roughshod over any notion of justice, fairness and the rule of law in its insatiable appetite for wealth. Of course, England was far from being a modern constitutional monarchy in the sixteenth century. Nevertheless, proponents of English exceptionalism love rolling out a narrative that explains how our fundamental rights and liberties as ‘free-born Englishmen’, first set down in Magna Carta and enshrined in common law, have been passed down to us through the centuries.

It is as much myth as reality, of course. Magna Carta says nothing about fundamental liberties, let alone parliaments, human rights and democracy; it was a document drawn up by the barons in their tussle with the king of the day. Meanwhile, Penn shows how, during the reign of Henry VII nearly 300 years later, the king and his chosen advisers made a mockery of any sense of fairness, employing an army of spies and informers as they targeted well-to-do individuals, threw them in jail and plundered their wealth with impunity. In order to help secure an orderly transition of power after the king’s death in 1509, one of his son’s first acts was to issue a general pardon making clear that in future justice would be “freely, righteously and indifferently applied”. Needless to say, it wasn’t.

Having being shocked and dismayed by Love, Paul Gambaccini, Winter King reinforced anxieties about present-day ‘rule of law’ issues, not least the principle of an impartial justice system. Rights we think of as fundamental suddenly no longer seem sacrosanct but rather up for debate. The government, to take just one example, has indicated that it intends to look at the role of the Supreme Court, with a view to clipping its wings.

Recent events in the USA, meanwhile — and the possibility that the Supreme Court may (again) play a decisive role in deciding who the next president will be — are deeply disturbing, especially when the choosing of the most recently appointed Supreme Court justice was such a nakedly political act (Trump himself openly declaring that he wanted his appointee Amy Coney Barrett on the bench before the presidential election on 3 November). The more I read of the political system in the USA, the more it seems an appalling advert for a written constitution, as much a corruption of ‘democracy’ as the Soviet Union and its satellites were a corruption of ‘Marxism’.

[Added: 28 October] This sense of angst was deepened after I watched a brilliant film documentary on the Sky Arts channel called White Riot, about the rise of Rock Against Racism in the years after 1976. The context was appalling levels of racism in the UK and the growing popularity of the National Front. The levels of everyday racism — and the behaviour of elements within the police force — were dreadful. Another reminder for people over, say, the age of 50 that the sixties and seventies were not the good old days.

Now for another Sam Bourne. This time, The Chosen One.

15 October

Blimey. This paragraph in The Chosen One made me laugh out loud. It was written in 2010, long before Trump came along to debase the office of American president. Sam Bourne is the nom de plume of Jonathan Freedland, a Guardian columnist who writes knowledgeably on, among many other things, American politics:

Americans could tolerate all manner of weaknesses in each other — especially if they were accompanied by contrition and redemption — but not in a president. They needed their president to be above all that, to be stronger than they were. Few men ever met that impossible standard. But a nation that looked to its leader to be a kind of tribal father never stopped expecting.

from The Chosen One, Sam Bourne (2010)

21 October

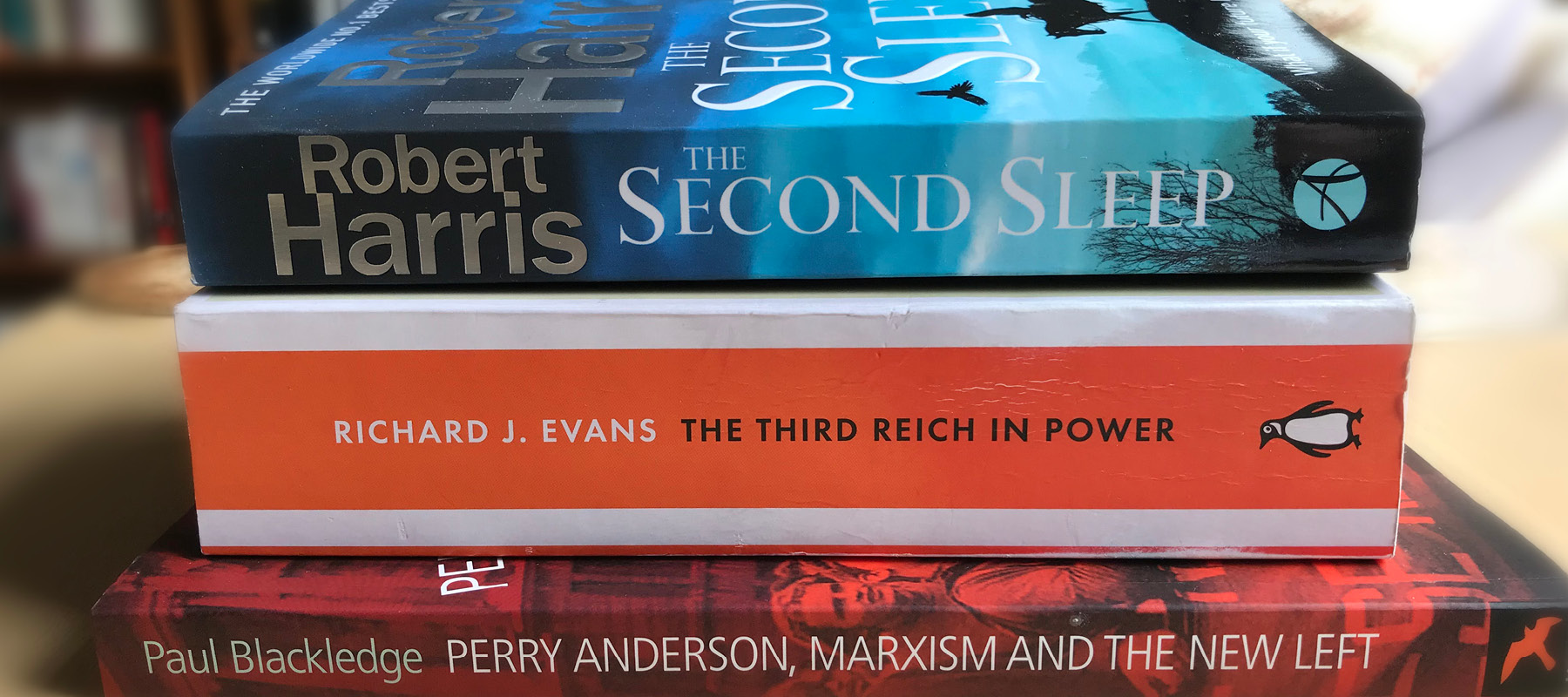

I finished the Sam Bourne book with the usual double helping. Brilliant, as ever. His publishers use the tagline ‘Suspense with substance’. Like a Robert Harris novel, you know that with Sam Bourne you are going to get not just all the elements of a pageturner but also cleverly constructed plots, well-researched detail and credible characters.

I dipped my toe into the murky waters of writing about politics with two blogs earlier this year, focusing particularly on what I described as ‘failures of leadership’. As Boris Johnson continues to demonstrate that he is not up to the job of being prime minister in a crisis, it is time to read the views of someone who really knows what they are talking about — the political commentator Steve Richards and his book The Prime Ministers: Reflections on Leadership from Wilson to Johnson.

23 October

A rare visit to a bookshop today, my first since July. So many interesting new titles (this autumn was apparently a bumper time for new books, many of them delayed because of the pandemic); lots to look forward to when they eventually appear in paperback. I spent some time browsing in the history section; again, lots to choose from, especially with Winter King whetting my appetite for pre-1600 history. I bought another Thomas Penn book, this one called The Brothers York. Fifteenth-century England is not something I know a great deal about. There was another book that I will probably pick up on my next visit — The Hollow Crown by Dan Jones, which, as a more general history of the Wars of the Roses, might have been a better place to start. I found his The Plantagenets very accessible a couple of years ago.

A book I have been intending to read for some time is the biography of Thomas Cromwell by Diarmaid MacCulloch. It has received sensational reviews, and will doubtless be an interesting companion piece to Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy, which has of course been similarly lauded. Two masterly writers of history; two contrasting approaches. I thoroughly enjoyed MacCulloch’s A History of Christianity and his book about the Reformation is practically shouting at me as well.

Much of the history I read is produced by left-leaning or avowedly left-wing writers, but I would like to think that I am open-minded enough to enjoy writers who look at history from a different vantage point. These are the things that matter: the thoroughness of the research, the writer’s judgements and the quality of the writing. Simon Heffer is very much a creature of the right, a long-time columnist for the Daily Mail. That said, I enjoyed his biography of Enoch Powell, and so the third book I picked up from the shop was his The Age of Decadence, a history of Britain between 1880 and 1914.

28 October

Steve Richards’s book on prime ministers since Harold Wilson is every bit as good as I thought it would be. He is someone whose political analysis I always listen to.

Although the book is set out with separate chapters on each prime minister bookended by an introduction and conclusion, one of its real strengths is that Richards is throughout comparing and contrasting them — what was similar and different in terms of their qualities, their approach, the events that confronted them and so on. It is an excellent and stimulating work of analysis and ensures that he does not get bogged down in unnecessary narrative.

As the subtitle says, his theme is leadership, and he continually returns to his ‘lessons of leadership’ — where it was demonstrated, where it was lacking, leadership traits that tended to produce good outcomes, and traits that contributed to bad outcomes. You probably won’t agree with every judgement he makes but, having been a watcher of politics for decades, he is a compelling and authoritative voice.

One criticism I would make of the book is that the writing lacks a bit of polish. It is the first Steve Richards book that I have read, but I am assuming it is connected with how the book came together. Most of the chapters are based on a series of unscripted straight-to-camera broadcasts (à la AJP Taylor) that he did on the Parliament Channel. As I say, he is constantly comparing and contrasting prime ministers, so there is inevitably some repetition. But it is noticeable how often particular words are repeated, sometimes within the same paragraph.

At one point, for example, I think I counted three uses of the word ‘fleetingly’ on the same page. The word ‘slaughtered’ (not my favourite word anyway) crops up more often than in a Stephen King novel — as in, ‘The Conservatives were slaughtered at the 1997 election’. Other errors (I think) include David Cameron’s ‘hug a husky’ policy (wasn’t it ‘hug a hoodie’?) and (regarding Gordon Brown) ‘the means justified the ends’. Like Richard Evans’s The Rise of the Nazis, there is also a howler in paragraph one of page one: “Boris Johnson, who entered Number Ten following the seismic general election in 2019.” It is curious that such errors were not corrected for the paperback edition.

Radio Blah Blah: Records and Record Buying in 1977

Giving away my record collection about ten years ago — all bar a couple of rarities — was an easy decision to make. Vinyl might once again (in 2020) be the cool way to listen to music, but not a decade ago, a time when record shops were an endangered species. Besides, there is no turntable in the house to play them on and I have CDs of everything I used to own, many with remastered sound and/or additional tracks.

Dusting off the old vinyl in the loft to help me compile a list of the first records I ever bought is not, therefore, an option. The official charts website will instead be my trusty guide through the gathering gloom of failing memory.

This ought to be easier with singles than with albums. Record shops used to stock albums going back years, but singles carried more of a ‘sell by’ date. Most shops sold older singles as well, usually in tightly packed, randomly ordered rows — and no doubt I picked up one or two singles cheaply long after they had fallen out of the charts — but I am fairly confident that I bought everything mentioned below when it was actually in the charts, making it possible to establish a more or less accurate timeline.

First, some pre-history.

My parents were not pop-music people. The only pop records I recall in the house when I was young were a couple of early Beatles EPs and Teenage Rampage by The Sweet (still my favourite Sweet song). That dates the memory to about 1974. Later there was a copy of Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody, presumably bought by my brother, who is older than me. The less said about my impromptu science experiment — playing the b-side using a nail as a stylus — the better. Hint: It is a one-time experiment.

I was too young to watch Van der Valk on television (early 1970s, with Barry Foster as the title character) but was obsessed with the theme tune, played by the Simon Park Orchestra. Eye Level reached No 1 in 1973. There was also a version with words sung by Matt Munro called And You Smiled. We had an album of popular TV themes as well. Favourites of mine, probably not on the album, included The World at War, Colditz and The Avengers.

I was a kid; there was inevitably a novelty single or two. One was a spoof song called King of the Cops, featuring somebody doing impressions of TV detectives to the tune of King of the Road by Roger Miller. The other was Trail of the Lonesome Pine by Laurel and Hardy, the beginning of a lifelong affection. I was gutted that it peaked at No 2, unaware that the song in its way was Bohemian Rhapsody. Over the years I have agonised every time a Queen single has stalled at No 2 — it is quite a list — so that probably counts as a bit of irony.

We bought our first music centre in about 1976: a radio, record player and cassette player, all in one. It meant that you could tape things directly from the radio or from a record, so the quality of the recording was good. I remember endlessly playing and re-playing a BASF C60 cassette with only four songs on it. One was definitely Mississippi by Pussycat and another was If You Leave Me Now by Chicago — so probably October or November 1976. The other two may have been Under the Moon of Love by Showaddywaddy and either Dancing Queen or Money Money Money by Abba. More about them shortly.

And so to January 1977. Jim Callaghan had taken over from Harold Wilson as Labour prime minister the previous April, Jimmy Carter was just beginning his term in office as US president, and the Christmas hit When a Child Is Born by Johnny Mathis was still No 1 in the first Top 30 of the new year.

I was 10 and beginning to soak up music like a sponge. This included obsessing about the singles chart, frantically scribbling down every song as it was read out on Radio 1 before writing the whole thing up neatly afterwards. I then taped all the new entries off the radio, using a mini-library of cassettes, with the DJ’s waffle over the intro and outro of each song lopped off. There were cassettes for repeat use and one reserved for songs I liked. Cassettes came with a small plastic square in the top corner; breaking it stopped you from accidentally taping over the contents.

There is a familiarity about the Top 30s of January 1977, so I must have been a regular listener by this point. A few songs are admittedly a complete blank — Bionic Santa by Chris Hill? — but it is surprisingly easy to remember the ones I hated. The chart of 23 January features Don’t Cry for Me Argentina by Julie Covington, When I Need You by Leo Sayer and David Soul singing Don’t Give Up On Us Baby. The entire universe watched Starsky and Hutch but it was obvious even to a 10-year-old that ‘Hutch’ wasn’t No 1 because of his singing voice.

The new chart was announced on Radio 1 on Tuesdays. Top of the Pops was on BBC One on Thursdays and there was a weekly chart show on the radio on Sundays — the Top 20 at first, later morphing into the Top 40. Knowing the exact order of songs to be played, this is where the taping mainly happened. Presented by Tom Browne back when I first started listening, it was a simultaneous broadcast on Radio 1 and Radio 2 — and in glorious stereo. Radio 1 itself was only in mono. As the reception, particularly after dark, was awful, it made recording anything from it a waste of time.

The chart of 30 January features a couple of 7-out-of-10 songs by groups I now listen to a lot: Don’t Believe a Word (Thin Lizzy) and New Kid in Town (the Eagles). But only one song grabbed me at the time: More Than a Feeling by Boston. It remains a huge favourite, a definite maybe for my yet-to-be-written list of the 20 best songs by 20 different artists (there are about 50 songs on that particular shortlist). I didn’t buy it, but the song later featured on a fairly obscure film soundtrack album that I got sometime in 1978 called FM.

And so we get to 6 February 1977.

Boogie Nights (Heatwave), Don’t Leave Me This Way (Harold Melvin and the Bluenotes) and Chanson d’Amour (Manhattan Transfer) have joined Leo Sayer, Julie Covington and David Soul at the top end of the charts. But new in at No 30 is Rockaria by ELO — I think, my first ‘proper’ single.

I picked up a great-value box set of the entire ELO catalogue on CD not long ago. Their first few albums, in particular — featuring Roy Wood as much as Jeff Lynne — are excellent and unexpectedly ‘proggy’ and experimental in places. A New World Record was their big commercial breakthrough; Rockaria was one of several singles from it. Beyond the reference to Beethoven, the lyrics seemed like gobbledygook. I probably liked the song for the ‘novelty’ operatic voice and the feel-good, upbeat tempo.

A month or so later and Knowing Me Knowing You is dominating the charts. It is blindingly obvious to me now that Abba were exceptional — classic pop tunes, brilliant arrangements and surprisingly dark lyrics — but I detested them at the time. David Bowie’s Sound and Vision is also in the top 3. Apart from the catchy riff, I liked its unusual structure: a short piece anyway, the vocals only come in halfway through. This was the start of Bowie’s Berlin period when he did some of his most influential work, though it didn’t sell particularly well by his standards. Sound and Vision was his last really big hit until Ashes to Ashes in 1980. Even Heroes, released later in 1977, was not much of a commercial success.

Once I was buying albums, most Saturdays involved touring the record shops of Wigan, principally Javelin and Roy Hurst’s, who in an act of wanton vandalism routinely stamped their name and address in ink on inner sleeves. But on this particular occasion in April I walked down to Mr Records, a local shop on the main road in Pemberton — long gone now, of course (the shop, not Pemberton) — intending to buy another single. Have I the Right by the Dead End Kids, No 6 on 24 April, was top of the shortlist, though 10cc, the Eagles and Peter Gabriel all had records out as well. Solsbury Hill was Gabriel’s first solo single after leaving Genesis. It is still one of my favourites; even as a 10-year-old I must have liked it.

Sad to say, I didn’t choose any of them. Instead — idiot alert — I bought the latest Top of the Pops album. The vinyl equivalent of the Turkey Twizzler, Top of the Pops albums were cheap and full of shit. Singles probably cost about 90p, albums perhaps £3.50. My weekly pocket money was 50p, let’s say, so I could afford a record every few weeks. A Top of the Pops album featured a dozen or so current hits — the Now! of its day — at a bargain price of about £1.20. Cheap but, alas, not cheerful. None of the tracks were original versions; they were all played (badly, if memory serves) by an in-house band. The one and only attractive thing about a Top of the Pops album was the model on the cover.

No such schoolboy error a week or two later, buying what was probably single number two: Hotel California by the Eagles. Like Rockaria, it is unusual and distinctive — six minutes plus, with a lengthy introduction and, of course, perhaps the greatest twin-guitars solo of all time. Definitely a thing for guitars, then. In our first music lesson at my new school in September we were asked what instrument we would like to learn; I wrote ‘electronic guitar’. Songs with offbeat arrangements seem to be high on my list, too — soon after buying Hotel California, I got 10cc’s Good Morning Judge, a clever, quirky song by a clever, quirky group.

Another stone-cold classic (unknown to me) in this week’s chart is Smoke on the Water by Deep Purple. Also up there is the ultimate earworm, Mah-Na, Mah-Na by the Muppets, and a fantastic but only moderately successful song called Lonely Boy by Andrew Gold that often gets a mention on Ken Bruce’s Pop Master quiz.

The charts tended to behave in a fairly predictable way: perhaps five or six new entries on the Top 30, with the highest new entry and the highest climber always getting a special mention. Going Underground by the Jam was the first single I remember actually entering the chart at No 1, a few years later. It is the most uneven double A-sided single I know: Going Underground is one of the Jam’s best songs and Dreams of Children one of their worst.

The highest new entry of 29 May is God Save the Queen by the Sex Pistols, in at No 11. Listening to the Sunday chart rundown I wait, fingers poised above ‘Record’ and ‘Play’.

“In at No 11, the highest new entry this week is God Save the Queen by the Sex Pistols … and at No 10 is OK by the Rock Follies …”

They didn’t play it. They didn’t play God Save the Queen. ‘Why not?’ was what I wanted an answer to. What did I know of BBC bans and names like Johnny Rotten and Sid Vicious. Lyrics like “fascist regime” were yet more gobbledygook. By the following week it was No 2, just beaten to No 1 by Rod Stewart. Again it wasn’t played. It is often said, of course, that God Save the Queen was actually the ‘real’ No 1, but that this was deemed unacceptable in the week of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee by the bowler-hatted powers-that-be.

Speaking of Her Majesty, at some point in the first half of the year two friends at school — Keith and Andy — mentioned the names Freddie Mercury and Queen. Somebody to Love was already on one of my cassettes, ending with the final note of the piano and DJ Tom Browne saying “Ha! Qu–” before I pressed the Stop button. I wasn’t even aware of their next single, Tie Your Mother Down, which didn’t trouble the scorers — a shame, as it’s their best ‘live’ video.

Good Old-Fashioned Lover Boy — actually ‘Queen’s First EP’ — was their next single. It may have been my next buy, though possibly one I bought some time later. DJs spoke of records ‘climbing’ the charts and then ‘peaking’ and ‘dropping’. Good Old-Fashioned Lover Boy was one of those that actually yo-yo-ed around: 36 … 29 … 21 … 24 … 19 … 17 … 23 … 22.

It is a puzzle why I bought nothing during the summer holidays because there were some great songs around between June and August — Telephone Line (ELO), Match of the Day (Genesis), Fanfare for the Common Man (ELP), Oxygene (Jean-Michel Jarre), Dancin’ in the Moonlight (Thin Lizzy).

A big summer hit was the groundbreaking I Feel Love by Donna Summer, with its Giorgio Moroder electronic pulse: it is yet another song that I loathed at the time but grudgingly appreciate nowadays. Meanwhile, Elvis Presley died in the middle of August. His single Way Down had failed to even reach the Top 40 but suddenly raced to the top of the chart when his death was announced. Much the same thing happened after the murder of John Lennon in December 1980. His then-new album Double Fantasy was No 1, as were the singles Woman and (Just Like) Starting Over — collectively his biggest hits since the Imagine single and album a decade earlier.

I bought We Are the Champions as soon as it came out in early October. Maybe all my money was going on buying Queen albums because my next single only entered the Top 30 several weeks later: She’s Not There by Santana. It’s a great song (an old Zombies hit) but it was definitely the spectacular and (for a single) lengthy guitar solos that caught my ear. That guitar thing again; not that I had any idea who Carlos Santana was.

In contrast, it was the synth solo that stood out on my next buy, another old song, though a re-release not a cover: Virginia Plain by Roxy Music. The second coming of Roxy Music in the late 1970s was not to my taste — too suave, too smooth — but Virginia Plain is from their earlier art-house period when Brian Eno was in the band. Whenever Eno later collaborated with musicians I listen to, he always added a magical ingredient, something deliciously quirky and offbeat: try The Waiting Room by Genesis or Memories Can’t Wait by Talking Heads (with that brilliantly jarring and discordant middle eight at roughly 2:01, before it all comes back in tune with the line “Everything is very quiet…”).

The chart of 6 November sticks in the memory. We Are the Champions was on its way to becoming a big hit, getting to No 6 the previous week. There was every expectation that it would be top 3 this week. Radio 1’s Paul Burnett always announced the new chart at 12.45pm on Tuesdays, straight after Newsbeat. He played the new No 5 through to No 2 and then did the rundown of the full Top 30, finishing by playing whatever was No 1. This all happily coincided with school lunchtime. My friend and fellow Queen fan Keith lived in the road behind school. We sat in his porch with a transistor radio listening in. I didn’t expect Champions to be either No 5 or No 4. It wasn’t. Nor was it No 3. Great, it was No 2. Except it wasn’t.

A non-mover at No 6. Cue the end of the world.

Well, not quite. The following week it jumped again to No 2 and looked all set to be their second No 1, only for Abba’s Name of the Game to crush our hopes. For two weeks running the top 3 was Abba, Queen and Status Quo’s Rockin’ All Over the World. Then Paul McCartney and Wings were No 1 forever with the turgid Mull of Kintyre (actually, nine weeks — the same, coincidentally, as Bohemian Rhapsody first time around).

A television advert for an album, presumably broadcast in the run-up to Christmas, acclaimed the band in question as rock gods who routinely sold out stadiums in America. Impressive stuff. I was duly intrigued. They were Yes, and the album was Going for the One. I bought the single of the same name, actually their second hit from the album. The first was the exquisite Wonderous Stories, the spelling of which looks like something Americans would write. The song’s writer Jon Anderson is from Accrington, but he is a West Coast hippie through and through. The b-side of Going for the One was called Awaken PT 1, which I cheerfully pronounced ‘pee tee 1’. The penny didn’t drop until I bought the album a couple of years later that it was ‘Part 1’: the full version lasts about 15 minutes.

That, then, was my year that was. Plenty there that I still like and listen to, as well as much that passed me by at the time. It was the following year — 1978 — that I properly started to build up my album collection. Some of the early punk singles were already charting by the end of 1977, but the likes of Genesis, Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin were on my horizon, and my brother was playing weird, heavy prog rock by a Canadian band with a singer who seemed to literally shriek about hallowed halls, temples of Syrinx and drinking the milk of paradise [my Rush appreciation here]. There was never really any doubt that it was rock music for me.

Mah-Na, Mah-Na.

I edited this blog in July 2022 when I published a companion piece, My first album buys.

Books, TV and Films, September 2020

2 September

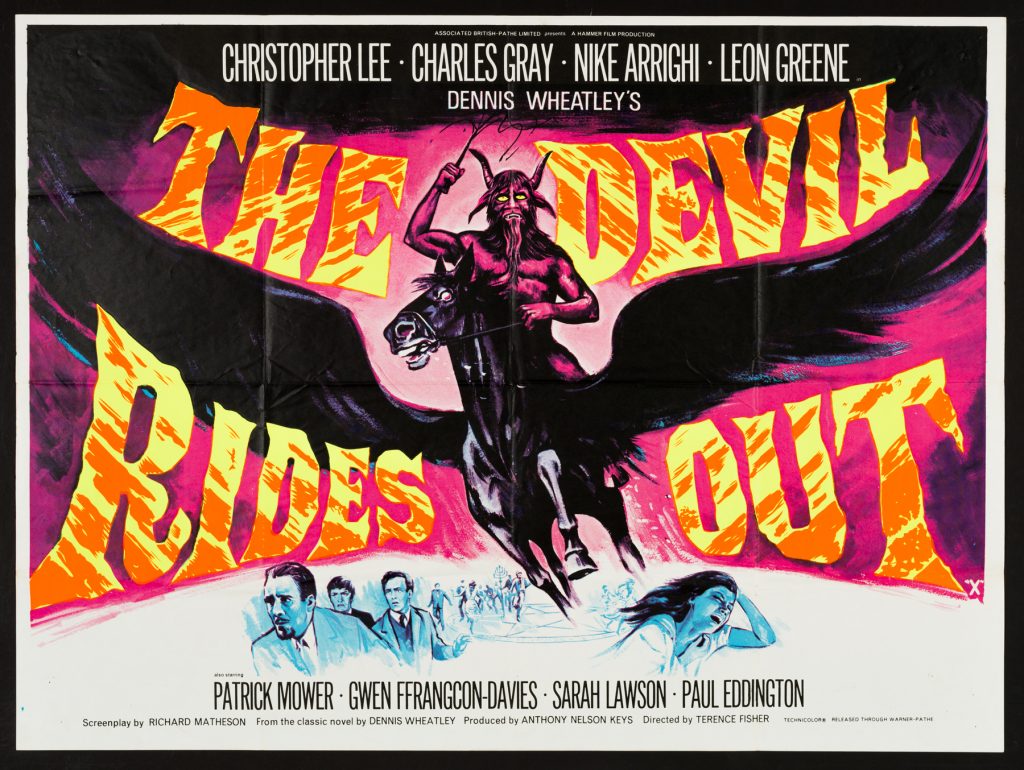

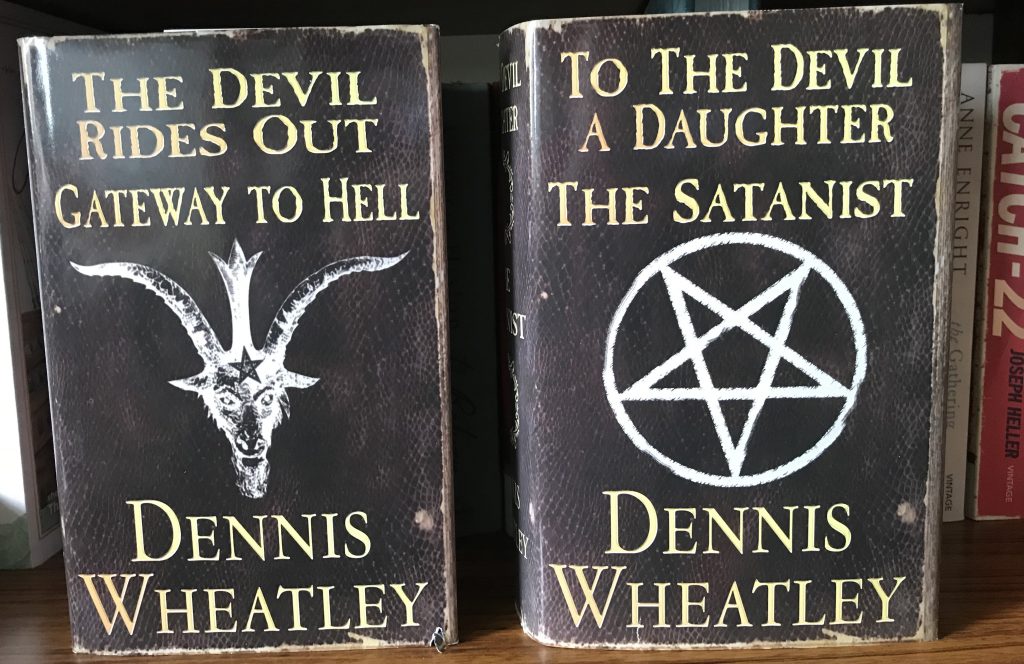

I re-watched The Ninth Gate, having referred to it in my recent Dennis Wheatley blog. Considering that it is directed by Roman Polanski — highly renowned, if controversial for non-film reasons; my favourite film of his is The Pianist — it plods quite a bit and the special effects aren’t up to much (the mysterious guardian angel’s ‘flying’ sequences are woefully bad). In a sentence, I much prefer the individual ingredients — antiquarian books, mysterious codes for summoning the devil etc — to the finished meal.

I have also watched Joker. I am not into the Marvel/DC stuff at all and haven’t seen any of the many ‘modern’ Batman films except the very first one with Michael Keaton (in which Jack Nicholson played the Joker). Does Joker even count as a ‘Batman’ film? I saw it as a searing indictment of the way American society deals with mental illness and its poor and downtrodden more generally.

4 September

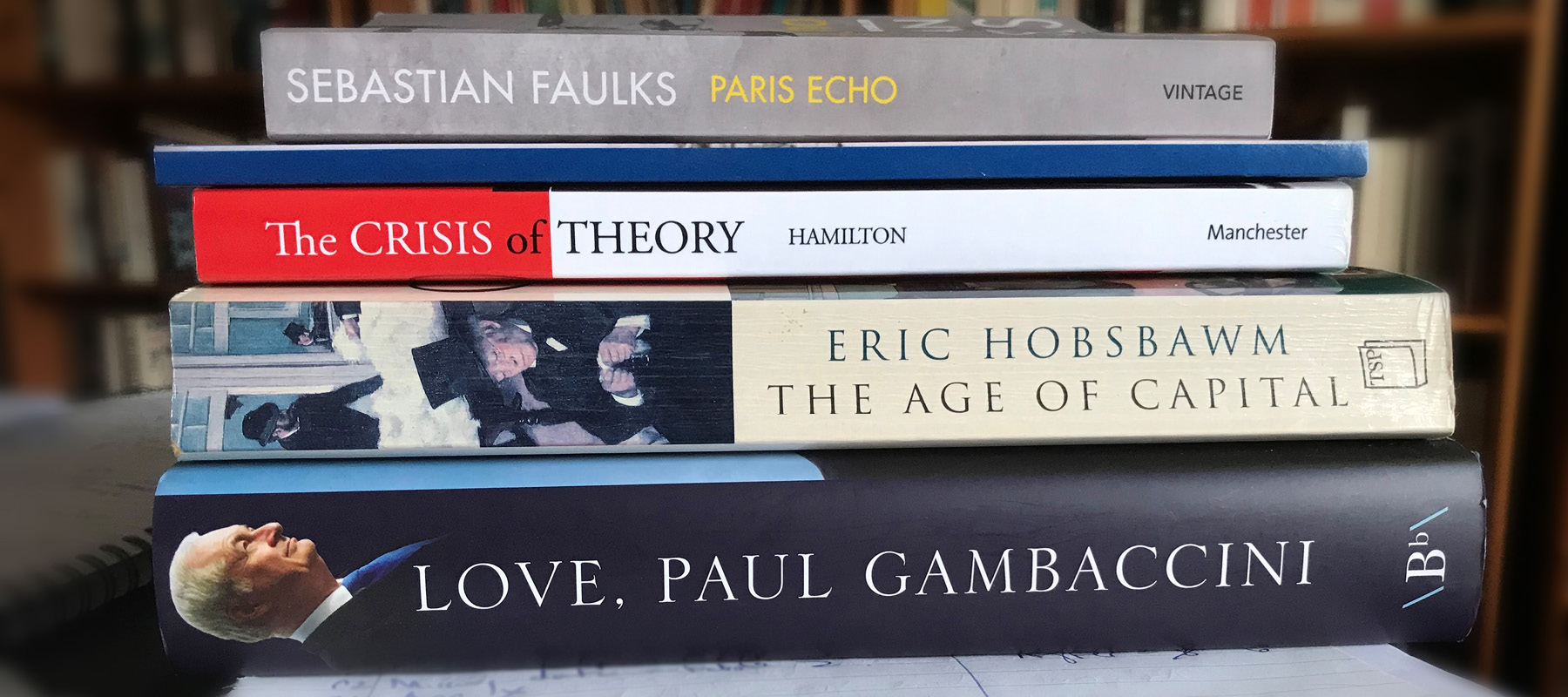

A book that has been on my must-read list for quite some time is Love, Paul Gambaccini, the DJ’s account of his year under arrest as part of Operation Yewtree, the police’s investigation into allegations of sexual conduct among ‘celebrities’ and other assorted VIPs in the aftermath of the Jimmy Savile revelations.

It is basically Gambaccini’s edited diaries for the year. As he himself says, if the police are going to arrest a journalist, they shouldn’t be surprised if the journalist keeps a journal. What happened to Gambaccini is shocking, and the book is a very uncomfortable read. You could put it down after a hundred pages without missing a great deal because Gambaccini’s life was basically put on hold for a year, despite the fact that he was never charged.

After his arrest it was like he was caught in a temporal loop. D-Day was roughly two months or so down the line, the date on which the police would inform him whether or not he would actually be charged. In those two months, as well as constant speculation on snippets of information gleaned from the police and other sources, there is much support from family and friends, many outbursts of anger, much cold shouldering and lots of eating out. Behind it all is a general build-up of tension as D-Day approaches. Then: complete anti-climax, as he is blithely informed that he is being rebailed for another few weeks. And so the cycle repeats. This nightmare went on for a year.

Gambaccini worries on 8 August: “What if the book I am writing is also met with a national yawn?” If so, that would be a shame because this is an important book, one that needs to be widely read. Sadly, I fear the worst; it doesn’t appear to have even made it to paperback.

The book is, as you would expect, full of rage. In subsequent media interviews (he went on to campaign for a change in the law on bail) he is careful to frame the debate in terms of two equal victims — the person assaulted and the person falsely accused. Apart from the outrageous way that Gambaccini and others were treated, one of the troubling things for me, as a long-time Guardian reader, is that Gambaccini — himself a lifelong Labour supporter and active fundraiser — is clear that his most vocal support came from the right-wing commentariat, the likes of Richard Littlejohn. From The Guardian, nothing. It has a different agenda.

And of course the book throws a spotlight on the shocking state of our justice system, which faces death by a thousand cuts. This case seriously stretched someone like Gambaccini, a relatively wealthy individual with access to extremely rich friends. The awful reality is that ‘justice’ in such cases is the preserve of the rich and almost certainly out of the reach of people of ordinary means.

Gambaccini himself — the ‘professor of pop’ — is a thoroughly likeable chap, which we knew anyway, I suppose. There is more than a little humour mixed in with the rage, and he can be forgiven the odd wince-inducing remark. Top of the latter list: “As a Royal Shakespeare Company veteran turned franchise icon might say, make it so.” It’s a reference to Patrick Stewart, if you aren’t a Star Trek fan.

5 September

Freddie Mercury’s birthday. Yesterday I asked some friends how old they thought he would be if he were still alive. Nobody went above 70. He would actually be 74 today. Although Queen’s first album only came out in 1973, they are of a similar age to others who broke through in the sixties. Jimmy Page and Roger Daltrey, for example, are both 76.

7 September

Time for some serious film watching ahead of the new football season. One that has been waiting in the My Recordings folder for far too long is The Post. Steven Spielberg, Tom Hanks, Meryl Streep; why on earth did I not watch this the day it was first shown?

Written around the publication of the so-called Pentagon Papers in the early seventies (which basically showed that the US government had been lying about the war in Vietnam for a very long time), it is a prequel of sorts to All the President’s Men, the story of the Watergate exposé starring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman.

This time around there is no Woodward and Bernstein. The star of the show is the Washington Post’s editor, Ben Bradlee, played by Tom Hanks. The film has an unashamedly liberal agenda and, though set fifty years ago, its central message — the freedom of the press is a sine qua non of a liberal and democratic society, holding those in power to account — resonates in the Trump world of ‘fake news’ and naked attacks on the media.

I wrote the following about Darkest Hour, the 2017 film about Winston Churchill in 1940:

Films about personalities and events from the past nevertheless reflect the mood, norms and expectations of the times in which they were made. With diversity and inclusion society’s current watchwords, any film about events dominated almost exclusively by socially privileged white men will throw up interesting challenges for director and scriptwriter.

Diogenes, Darkest Hour film review

I doubt there are many settings more “dominated almost exclusively by socially privileged white men” than the upper echelons of the Washington Post in the seventies. Thus, running in parallel with the journalistic scoop story, the script follows the tribulations of the paper’s owner Katharine Graham, who is played by Streep.

I don’t know anything about what really went on behind the scenes at the Post. Graham is portrayed in the film as a woman at first seemingly out of her depth, having been placed in the hot seat by the death of her husband. The decision to publish the secret documents could bankrupt the paper. Should she authorise publication or not? Eventually standing up to the (all male) board — with the great Bradley Whitford playing a deliciously sinister role, his naked chauvinism visible for all to see by the film’s end — she backs her editor.

12 September

Well, I have finally broken my unwritten rule of alternating between fact and fiction this year. A number of books have been shouting at me to be re-read, I think because I noticed that the Labour politician Lord Adonis has written a biography of Ernie Bevin. I am very tempted to re-read the third volume of Alan Bullock’s biography, but it’s about 900 pages (and the text is unusually small) so I will wait until I am a bit less busy.

The Adonis book reminded me of the biography of Aneurin Bevan I read a year or so ago by Nick Thomas-Symonds, who is currently the shadow home secretary. He might be a former Oxford academic and a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, but it was a really disappointing book. I am not a huge fan of ‘serving’ politicians writing books about their heroes. Having said that, I do want to re-read Michael Foot’s Bevan biography, if only to enjoy it as a literary treat (and, yes, I know, I didn’t enjoy Foot’s biography of HG Wells).

In the end I decided to re-read Age of Capital, the second volume of Eric Hobsbawm’s history of the ‘long’ nineteenth century. I re-read Age of Revolution last year, and I plan to get round to Age of Empire again at some point to complete the trilogy.

14 September

I watched the fourth and final episode of Lethal White, the latest TV outing for Strike, the London private detective created by Robert Galbraith, better known as JK Rowling. I have never actually checked but I assume that the pseudonym is at least in part linked to JK Galbraith, the famous liberal economist. Strike is something of a rarity for me: a drama that I found at the very beginning (I actually went back and watched The Cuckoo’s Calling on iPlayer last week), and I am so glad I did.

The plot of Lethal White is ridiculously convoluted and hard to follow (made even worse because I watched the episodes more or less as broadcast, with a week’s gap in between, and I have a memory like a sieve; normally I record them and watch the whole thing in my own time), but it didn’t really matter because much of the drama actually revolves around the relationship between Strike and his assistant Robin. Two convincingly drawn characters, a great ongoing will-they-won’t-they thing, and brilliant performances from Tom Burke and Holliday Grainger (who reminds me a bit of Jodie Comer, also sensational as Villanelle in Killing Eve).

15 September

After a run of first-class films I have hit a brick wall of sorts with Ad Astra. It’s one of those films which I think we are meant to regard as deep and meaningful, but it didn’t do a huge amount for me; maybe I wasn’t paying enough attention. I have never been a huge fan of first-person voiceovers: is it me or do they always sound phlegmatic and, dare I say it, bored?

I assume the echoes of Apocalypse Now, itself based on the novella Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad, are deliberate: a journey into the unknown; delusions of grandeur; the questioning of old certainties.

In its visuals I suppose it will be compared to 2001: A Space Odyssey. There were indeed some impressive scenes (none more so than the opening sequence where he plunges to earth from an impossibly tall structure that reaches into space). The extra-vehicular goings-on in Neptune’s orbit were stunning but completely ridiculous. The buggy chase across the Moon actually reminded me of Diamonds Are Forever as much as anything, and the Mars interiors looked like something from a Gerry Anderson set.

16 September

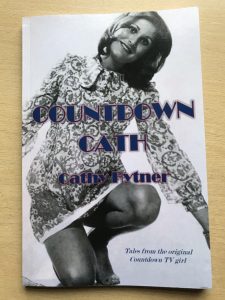

I am always amazed — perhaps ‘incredulous’ is the word — when some cultural or intellectual figure of note, quizzed on what they are currently reading, promptly reels off four or five titles. It is rare that I even have two books on the go at the same time. My brain just can’t handle it, and I also have a vague sense that it is disrespectful to the author. I have made an exception at the moment, if only because the second one isn’t actually a standard book as such. As well as Hobsbawm I am reading Countdown Cath.

The ‘Cath’ of the title is Cathy Hytner, best known as one of the original Countdown presenting team back in the early eighties. As I say, it is very different from the books I normally read. For starters, it is extremely slight — 80 pages, about 10 of which are of photographs. Nor is it a product of the ‘official’ book world. Rather, it is a more or less DIY effort, published with the help of a friend, I think. Don’t pick it up expecting a polished publication.

Covering the period from her childhood in the fifties to leaving Countdown in the late-eighties, this collection of memories was written in self-isolation during the lockdown of March onwards. In an afterword, Cathy describes the writing experience as “cathartic”. For the reader, meanwhile, the very first paragraph of a blurb on the opening page — “unwanted fourth daughter”, “neglected childhood years”, “hidden cost” — prepares us for what is to come.

It is an unvarnished and at times sad and deeply moving tale. Its mini-chapters (sometimes less than a page in length) — and particularly the repeated use of titles beginning with the words ‘Picture This’ — add to the sense that Cathy is candidly showing us snapshots from the life of a working-class girl from Manchester. It isn’t all grim up north. There is laughter mixed in with the tears and glamour as well as gloom. But, at a time when one side in the culture war rages that demands for equality are a sign that the world has gone mad, Cathy’s stories from the modelling and TV worlds of the seventies and eighties are a timely reminder of the abysmal way in which we are capable of treating each other — and, indeed, routinely did not all that long ago. A quick glance at Gyles Brandreth’s published diaries, Something Sensational to Read in the Train, confirms that producer John Meade was indeed a complete shit.

With a bit of imagination I can join the dots between the houses, shops and streets of Cathy’s childhood and my early-years visits to my grandmother’s house a decade and a half later. It was a warm, welcoming and loving household; I was lucky. But, even as a young child, I had a sense of the make-do-and-mend reality of Nanna’s day-to-day life. It wasn’t just the television that was in black and white. To slightly misquote Harold Macmillan, most of us have never had it so good. It is all too easy to look back nostalgically on the good old days that, in reality, never actually existed.

17 September

I finished the Hobsbawm book. As usual, he writes in the preface that the book is aimed at the general reader (his own Age of Revolution puts it best: “that theoretical construct, the intelligent and educated citizen”). I am intrigued to meet this general reader. As someone who has been reading history for forty years I find Hobsbawm’s histories never less than challenging: wide-ranging, learned and — despite his protestations — requiring more than a passing familiarity with at least the main events of the period. Curiously, my (paperback) edition shows the copyright as 1962, but it was in fact published in 1975.

For all Hobsbawm’s intellectual prowess the book does have serious flaws. The repeated references to Marx date it somewhat (and its unapologetically Marxist perspective paints the world in bleak terms). Despite its global canvas it defaults repeatedly to Europe, principally Britain and France. I will frankly have to re-read the chapter on the arts to get to grips with what Hobsbawm was arguing. More generally, for a lifelong champion of the so-called lower classes, his observations on culture are extraordinarily elitist.

The great Richard J Evans has written a brilliant biography of Hobsbawm, and it is to Evans’s The Pursuit of Power rather than to Hobsbawn that I would now turn if I wanted an overview of the nineteenth century.

22 September

Reading Eric Hobsbawn has led me back to EP Thompson, another great Marxist historian. I am re-reading The Crisis of Theory by Scott Hamilton.

Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class, published in 1963, is hailed as a classic, breaking new ground in terms of its subject matter and its methodological approach. He fell out spectacularly with Perry Anderson and the New Left Review circle of Marxists in the sixties and seventies. While they were under the spell of continental Marxists and a ‘cold’, structuralist approach to thinking about history and society — a sense that we are powerless in the face of ‘objective’ economic laws — Thompson emphasised consciousness and agency. He combined this with a fierce pride in the struggles of ordinary people throughout (British) history.

Some of Thompson’s ideas now seem hopelessly romantic — indeed, towards the end of his life he seems to have become disillusioned not just with Marxism but with the left more generally — but the values that underpin his ‘socialist humanism’ strike me as more relevant than ever.

24 September

After a run of non-fiction reading it was time to pick up a novel again, as per my new year’s resolution. I have read pretty much everything by Sebastian Faulks, including On Green Dolphin Street earlier this year. I count Human Traces as one of my all-time favourite books. For some reason I haven’t yet read his latest — Paris Echo — even though it was published in paperback in 2018. So, here goes …

29 September

Paris Echo has all the familiar Faulks trademarks, not least an incredible sense of place. If I had to sum up in one word what I love about Faulks’s writing, it would probably be ‘interweaving’. It is there in all his books but is absolutely central to this one — the ‘echoes’ of the title. One story weaves in and out of another; characters intermingle, one with another; the past intersects with the present; locations intersect with stories. It is all wonderfully, wonderfully crafted. Overarching it all is a deep love of, and respect for, the past.

We are back in Faulks’ beloved France. The two central characters are Hannah, an American historian researching women’s experiences in Paris during the Occupation, and Tariq, an undocumented Moroccan immigrant, whose family history has been shaped by France’s colonial past. Both arrive in Paris looking for something, though neither is clear quite what that ‘something’ is.

The novel is full of mystery. There is the fragility and contingency of Hannah’s work, as she tries to reconstruct the past. As a historian by training and someone who reads a lot of history, I was struck by the observation that people who live through ‘historic’ events might not experience them as such, especially if their most pressing day-to-day priority is simply survival.

There are many unanswered questions surrounding Tariq, too. What was the traumatic experience in his family’s recent past? What is the nature of his out-of-body ‘autoscopic’ experiences? Is Clemence real or just a drug-induced hallucination? For the reader it is frustrating — but fitting — that Faulks doesn’t give us any easy answers to these and other conundrums.

Books, TV and Films, August 2020

1 August

With the football season at an end, there’s time to try out a classic film that I have never actually seen before — Ice Station Zebra — ‘classic’ in the very loose sense of a film with an all-star cast that turns up quite a lot on television. It came out in 1968 and is based on a novel by a famous thriller writer of the day, Alistair MacLean. I have only ever read one of his books, I think (Partisans, a book-club buy from the early-’80s), but I automatically place him in the same bracket as Jack Higgins — exciting, page-turning plots let down by unexciting, predictable and poorly drawn characters — whose books (the most famous is probably The Eagle Has Landed) I am a bit more familiar with.

Ice Station Zebra is set during the Cold War, but it has the feel of many of the Second World War movies that were popular in the sixties — the likes of The Dirty Dozen and Where Eagles Dare (which is also by MacLean). Watch any of the above and expect secret orders passed down from on high, plenty of suspense interspersed with bursts of derring-do, clean-cut heroes and dastardly villains, courage and betrayal, few if any women, and lots of cigarette smoking.

Life inside the submarine is suitably claustrophobic and, like Where Eagles Dare, the film features stunning location photography, though the scenes at the Zebra station on the polar ice-cap are poorly realised in comparison. Rock Hudson is the cool-under-pressure captain, Ernest Borgnine struggles to convince with his dodgy Russian backstory and even dodgier accent, and Patrick McGoohan plays a secretive (and, stretching it quite a bit, vicious) spook to type: it could be the exact same agent as the one he portrayed in a Columbo episode a few years later (Identity Crisis, the one in which he kills Leslie Nielsen).

2 August

More television (well, Amazon Prime). This time, Knives Out. I wasn’t too sure what to expect; my guess, based on media advertising, was some kind of ingeniously plotted farce or spoof. Actually, it is more like an homage and didn’t disappoint.

Once I got over Daniel Craig’s southern drawl (at first I thought his voice was badly overdubbed) there was much to enjoy, even if it was a bit silly in places — the suspect who is unable to lie without immediately vomiting, for example. It borrowed ingredients freely (though respectfully) from the Agatha Christie recipe — the labyrinthine house; the sudden and suspicious death of a wealthy patriarch; the family squabbling over the will; the everybody-is-a-suspect-and-has-a-shaky-alibi routine etc.

All very 1930s. In one respect, however, Knives Out seems to be making a very up-to-the-minute political statement. The family members — white, wealthy, privileged — are greedy, duplicitous and self-serving. They each make a show of welcoming the Latina nurse into their family and their home, but it is all pretence (their lies exposed when she unexpectedly receives the bulk of the fortune of the deceased patriarch). It is the nurse who, throughout, is the one genuine, kind and likeable character, determined to do the right thing. It’s hard not to see it as a commentary on the Trump administration and the state of US politics.

6 August

I had to re-read On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan, having watched the film a few weeks ago. At just 160 or so pages it’s really a novella. It’s quite extraordinary how McEwan is able to say so much in so few words.

A million years ago, sitting my A-level general studies exam, I answered an essay question that basically asked us to consider whether film adaptations of books can ever do justice to the original text. I was reading a lot of Sherlock Holmes at the time and, if memory serves, based much of my answer around a discussion of the Basil Rathbone/Nigel Bruce films. I imagine I focused on the difficulty films have in exploring the inner voice (though it’s doubtful I used quite those words).

Films do narrative well. Sometimes — as in the ending of Stephen King’s The Dead Zone — they improve on the original text. But they have a harder task than books at exploring character in a nuanced way. Not the stock ‘goodies’ and ‘baddies’. That’s all too easy. Nor do I really mean the Bildungsroman-style character arc in which a person undergoes some sort of metamorphosis over the course of the film. I am thinking more about finding a way to portray the jumble of sometimes contradictory feelings, moods, emotions and urges that most of us feel most of the time. How to portray someone like Florence Ponting from On Chesil Beach, for example.

12 August

Being in a ‘horror’ frame of mind after just writing the first part of my blog on Dennis Wheatley, I decided to watch Interview with the Vampire. It came out in 1994, but I have never see it before. I won’t be in a hurry to watch it again any time soon. I know that the Anne Rice novel, which I haven’t read, was hugely popular but I found the film — and the performances of Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt — less than enthralling.

Perhaps it was trying too hard to be sophisticated. Much more to my liking was Lust for a Vampire, shown on a cable channel the other day. It’s typical of those classic Hammer productions that don’t take themselves too seriously. Predictable plot. Stage-y sets. Generous helpings of tomato-ketchup blood. Dodgy overdubbing. And happy-go-lucky, nubile serving girls who speak perfect English despite the central European location and who think nothing of going off alone despite a number of unexplained deaths in the local area of other happy-go-lucky, nubile serving girls.

Scars of Dracula (starring a very young Dennis Waterman and Jenny Hanley), released in 1970, is rather tame, but in a sign of changing times Hammer upped the sex quotient for its Karnstein trilogy: Lust for a Vampire, The Vampire Lovers and Twins of Evil all feature more than a hint of lesbianism and scenes of not-exactly-central-to-the-plot female (mainly) upper-body nudity.

It’s all harmless stuff — the most explicit thing about them are the original promotional posters — and quite ridiculous that films like these still seem to be rated 18.

13 August

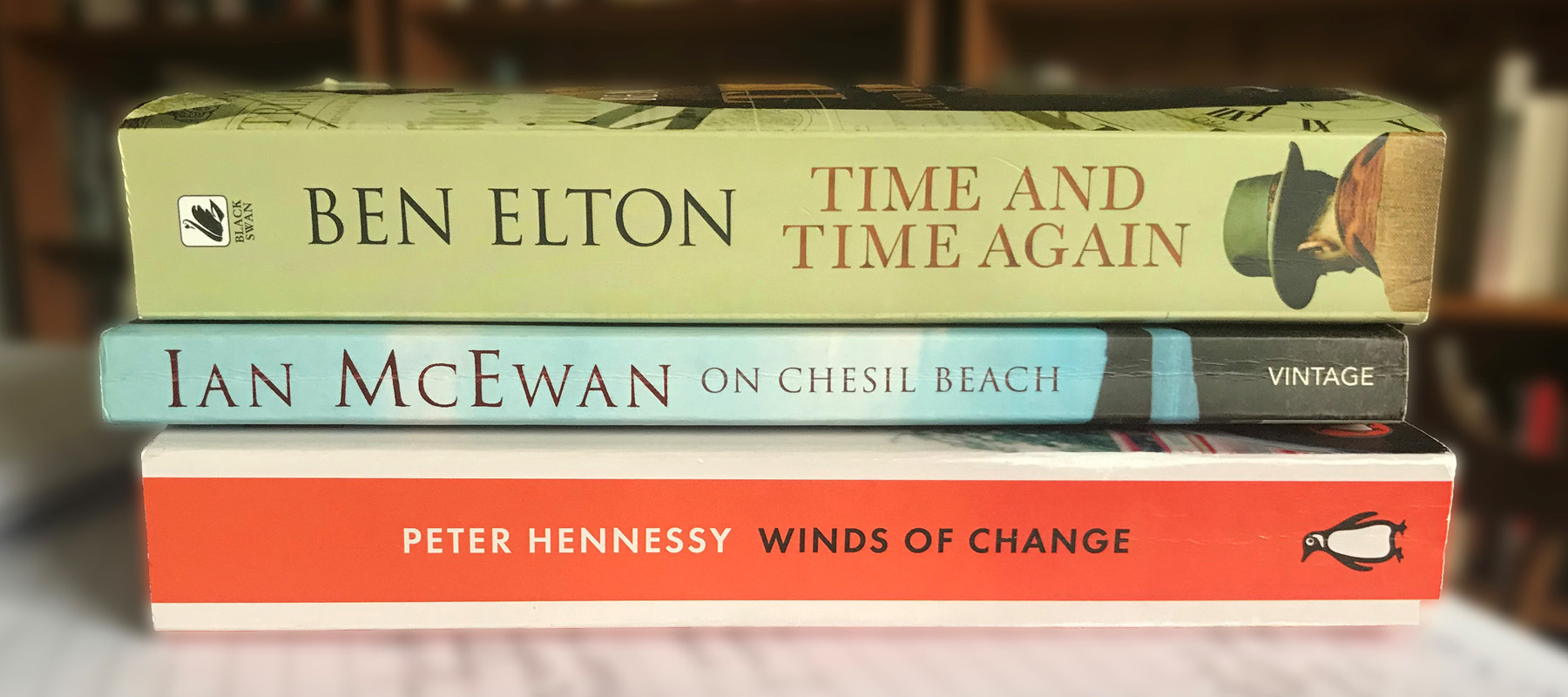

After Robert Harris’s brilliant The Second Sleep, here’s another treat, bought on the day it came out in paperback: Winds of Change, the latest volume in Peter Hennessy’s postwar history of Britain, this time covering the early sixties.

I don’t watch a huge amount of television and I am conscious of having missed out on loads of great programmes over the years. When the lockdown first kicked in, I decided to try out something from BBC iPlayer. As a fan of the spy genre I settled on Spooks. Ten series. Eighty-odd hour-long episodes. Enough to keep anyone busy. I finally finished it this week.

A big surprise — I have only just found this out after looking up Spooks on Wikipedia — is that it was a production-company and not a BBC decision to end the programme. That’s quite refreshing. Even allowing for the fact that I was watching it over a relatively short span of time, it felt by series 10 like enough was enough. Another episode; another day in Spookworld. Another terrorist outrage averted here; another corrupt top-level appointee or politician unmasked there. Another intelligence agency up to no good here (take your pick — the CIA, the FSB, Mossad); another dodgy organisation with global tentacles up to no good there (the slightly preposterously named ‘Yalta’, for example).

It was smart. It was sexy. It was tech-y. It was exciting. Was it also a little too predictable? As soon as it was revealed in series 10 that new spook Erin Watts had a young child, it surely wouldn’t be long before the said child was kidnapped or murdered by bad guys. And indeed it wasn’t.

Somewhat predictable, then … except in one regard: the death rate among lead characters. Everybody was expendable. Nobody, but nobody (except Harry), was exempt, and not just in end-of-series cliffhangers either — from Helen in the second episode of series one to Danny, Zaf, Adam Carter’s wife, Adam Carter himself, and finally (the saddest one of all) Ruth. It’s a long, long list.

20 August

Peter Hennessy’s Winds of Change is excellent. No surprises there. I first discovered Hennessy via a work colleague who had been an undergraduate student of his at Queen Mary’s in London and spoke of him in reverential terms. I read Whitehall, his huge book about the history and inner workings of the civil service. He is a trusty guide and absolutely authoritative. He is a capable broadcaster, too; his is the voice I always listen out for as his media role as both ‘talking head’ and presenter has flourished over the last couple of decades.

In the preface to the first volume of his history of postwar Britain, Never Again, published in 1992 and covering the Attlee government, Hennessy refers to a project spanning the years from 1945 to 2000. Plans obviously changed. There has been at least a decade between each volume. The second, Having It So Good, encompasses the whole of the fifties. This volume covers only the years 1960 to 1964 but much of the media comment surrounding the book’s launch is of it completing a ‘trilogy’.

It is little surprise that Hennessy became a go-to academic for expert, objective analysis. As well as having encyclopaedic knowledge, he is also at ease in front of a microphone. And he writes like he talks, mixing magisterial insights with gossipy asides. “Poor Selwyn!”; “Very Rab.”

It helps that he has interviewed pretty much everybody that matters in British politics over the years. Liberal use of ‘private information’, often in footnotes and end-notes, combined with recently declassified documents and unpublished minutes of key meetings reinforces the sense as you read Hennessy that you are being offered privileged access to little-known, hush-hush stuff.

Hennessy specialises in what he calls the ‘hidden wiring’, the workings of government not ordinarily in the public gaze. This at times leads him to focus on such matters at the expense of other areas of importance and interest. For example, we return repeatedly to official (and top-secret) preparations for government in the event of a Soviet nuclear attack. Okay, but this reader at least would have expected in a history of sixties Britain a bit more than we get on social and cultural developments.

Hennessy has a keen sense of the absurd and the quirky; there’s half a page devoted, for example, to Selwyn Lloyd’s dog, Sambo. More often than not, such you-couldn’t-make-it-up stories — as in the extraordinary arrangements for the prime minister to use the AA roadside-phone network to contact the Number 10 switchboard in the event of a nuclear attack taking place when he was away from London — tell us something rather revealing about the state of Britain at that time.

I watched Lady Bird, another hugely enjoyable film starring the excellent Saoirse Ronan. It has a similar coming-of-age, teenage-angst theme as On Chesil Beach, though ultimately it’s less dark. It’s a tale of two strong-willed women — a mother and her daughter — and of things left unsaid.

24 August

I knew that after reading The Second Sleep I had to go back and re-read Ben Elton’s Time and Time Again, another novel that plays around with history. I think I have read everything by Ben Elton, ever since his first novel Stark had me laughing out loud thirty or so years ago. For a long time he specialised in satirising whatever was the latest pop-culture obsession — drugs, talent shows, Big Brother-style fly-on-the-wall TV. Some of his books I enjoyed more than others. I loved Blast from the Past, but Inconceivable was less good. Some of his later efforts have been more historical — The First Casualty (the First World War) and Two Brothers (Nazi Germany).

This time around (no joke intended — the book concerns going back in time) the predictability of the characters in Time and Time Again grated a little. They are all larger than life, versions of Elton himself in a way. Hugh ‘Guts’ Stanton is the biggest, baddest ‘survivalist’ soldier around. Bernadette Burdette is the beautiful, loquacious free spirit he meets on a central European train, her every thought and utterance typical of the 2010s rather than the 1910s. Least believable of all is the foul-mouthed distinguished professor of history at Cambridge University who seems to think like a Sun editorial. Okay as a one-off maybe but then we meet the Lucian Professor of Mathematics, an “appalling media tart” who wears a ‘Science Rocks’ badge and says things like “Why in the blinking blazes was old Isaac getting his knickers in a twist?” Old Isaac being Sir Isaac Newton.

Nevertheless, one thing that Elton does brilliantly is plot. He is astonishingly imaginative, and although the basic set-up here is familiar — travelling back in time to change the past and therefore the future — Elton packs it with plenty of twists and turns. One, in particular, had me gasping (on p441 of the paperback). Nicely done, sir. I also liked the fact that the infamous assassination in Sarajevo happens (or rather, doesn’t happen) halfway through the book, allowing Elton to have plenty of fun with counterfactual histories.

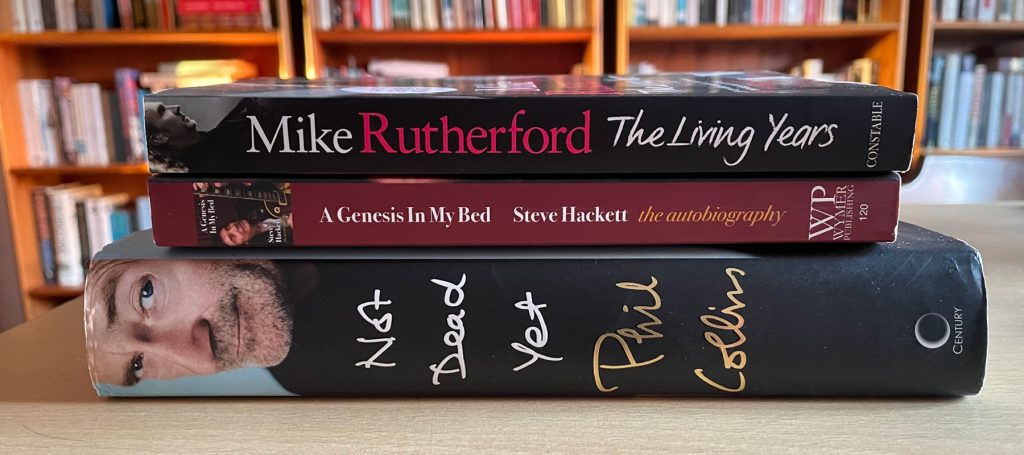

London 1980: Genesis Bootlegs

Genesis, 1980 — and this time it’s personal.

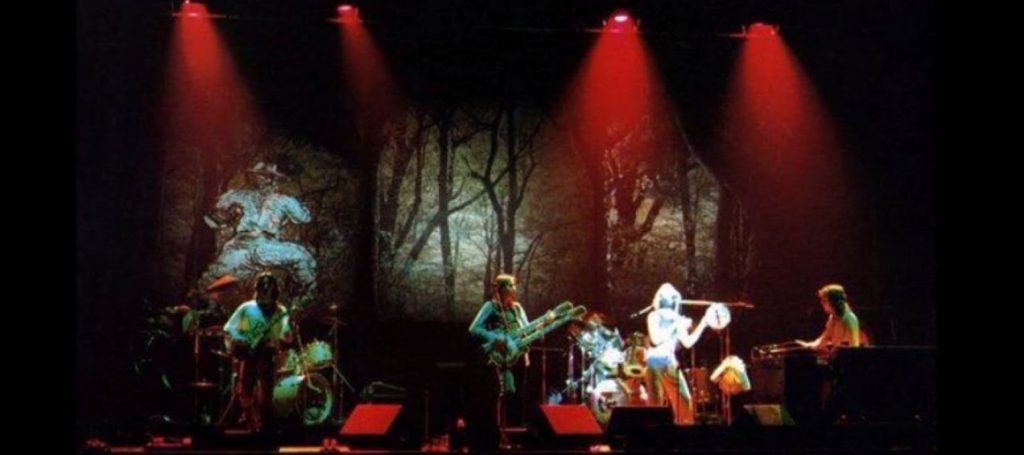

By the time I was discovering rock music as a young lad in the late-‘70s, the ‘classic’ era was already over and its surviving big beasts were fast mutating into something altogether cuddlier and more house-trained. Led Zeppelin’s In Through the Out Door featured as much piano as guitar and even a flirtation with synth-pop. Tormato by Yes offered up nine songs (and an awful album cover), only three fewer than the total number of tracks on their previous three releases, one of which was a double. Perhaps oddest of all was Pink Floyd — plus schoolchildren — with the Christmas number one single in 1979.

I got into Genesis sometime in 1978 — or possibly 1979 — via And Then There Were Three. Within a few months I had caught up with their back catalogue. Duke, released in March 1980, was the first Genesis album that came out in ‘real time’, as it were.

Their approach to writing some of the tracks that ended up on Duke has echoes of the pre-Trespass days, this time with Phil’s home substituting for Richard Macphail’s parents’ cottage in Surrey where much early writing and rehearsing had been done. It was collaborative and spontaneous, and came about in part, perhaps, because of the lack of individual material to hand. With Phil away trying to rescue his marriage, Tony and Mike had both released solo albums. On his return Phil, too, had begun writing and recording material that eventually became Face Value.

The Armando Gallo book, my Genesis bible at the time, ends in 1979 with talk of an extended piece of music, which this young fan — who was playing Seconds Out to death at this point — naively interpreted as a return to musical adventures à la Supper’s Ready and The Cinema Show. Alas, it was not to be. The piece was broken up into its component parts, the radio-friendly Turn It On Again and Misunderstanding became successful singles, and a ‘new’ Genesis-for-the-eighties came into being.

Forty years on I look back on these years — 1978 to 1980 — as a time of transition, a staging post on the journey to the brave new world of commercial success. Duke continues along the more accessible path mapped out by And Then There Were Three. But both albums also contain more than a few moments for even the most diehard fan of ‘old’ Genesis to savour — extended instrumental passages, soaring choruses, lyrical references to maidens fair and foul. An alluring mixture of familiar fragrance and flavours strange, you might say.

But it didn’t feel like that at the time — at least, not to this young fan. It actually felt like a huge and hugely unwelcome change of direction. It was as if they were forsaking their roots. Selling out.

Even the artwork — the cartoon figures, the childlike scrawl of the lyrics — reinforced these thoughts. It was all a bit too lightweight, too direct, too commercial. I avoided the new single (Turn It On Again), unlike my friend and fellow compulsive record-buyer Dave. Also a Genesis fan, he was generally more open-minded about chart music than I was. I probably picked up Duke, belatedly and grudgingly, a few weeks after its release.

And then, as Genesis transformed themselves during the early-‘80s, I took refuge in Foxtrot, Wind and Wuthering and the rest, leaving my doubts about Duke to fester and grow. To this day Duke strikes me as the weaker of the two ‘transition’ albums, a judgement more to do with the overall sound than with the quality of particular songs. Where Tony’s lush keyboards on And Then There Were Three wrap the listener in a warm embrace, Duke tracks such as Alone Tonight, Cul-de-sac and Heathaze sound colder and thinner to this (untrained) ear.

On this I am doubtless in a small minority. Genesis fans generally seem to regard Duke with huge affection. It was certainly a big seller at the time. Tony himself describes it in Chapter and Verse as his favourite album. Only relatively recently — perhaps after finally buying a copy of Tony’s A Curious Feeling five or so years ago, perhaps a little earlier — have I really made an effort to listen to Duke with fresh ears.

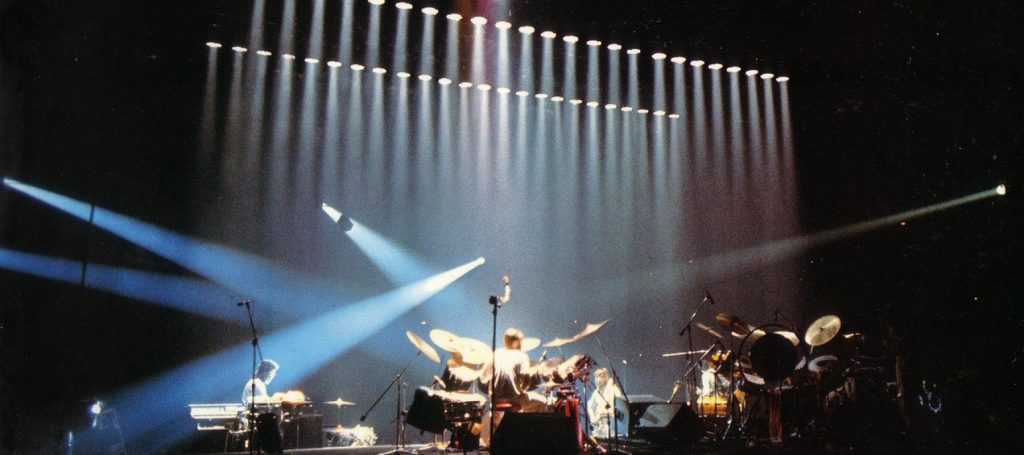

And so we come to the live shows, lengthy tours of Britain and North America. In addition to audio bootlegs — including high-quality recordings from Sheffield (broadcast on FM radio) and London — there is also a visual record of the tour. The London Lyceum shows on 6–7 May were filmed by the BBC. A very watchable video of the entire show is in wide circulation, though only a 40-minute edit was ever broadcast, initially as an Old Grey Whistle Test special.

Genesis had played only one British date on their 1978 world tour — at Knebworth. Phil ended the show with the promise of an extensive British tour the following year. Actually it ran from March to May 1980. And in the manner of Queen’s Crazy Tour a few months earlier, the focus was very much on a return to smaller venues, the likes of Exeter University and the Hexagon at Reading.

After the radical restructuring of the set list in 1978, its core remained in place for the 1980 tour. It ran roughly as follows:

Deep in the Motherlode / Dancing with the Moonlit Knight [excerpt] / Carpet Crawlers / Squonk / One for the Vine / Behind the Lines / Duchess / Guide Vocal / Turn It On Again / Duke’s Travels / Duke’s End / Say It’s Alright Joe / The Lady Lies / Ripples / In the Cage / The Colony of Slippermen [excerpt] / Afterglow / Follow You Follow Me / Dance on a Volcano / Los Endos / I Know What I Like / The Knife [shortened]

Genesis opening songs have been somewhat hit and miss over the years. The brooding intensity of Watcher of the Skies was perfect in its day. On the other hand, as I have written elsewhere, Squonk (used in ’77) isn’t one of their strongest songs, and it’s frankly a mystery why they chose to go with Land of Confusion on the final (1992) tour. For the first few shows on the Duke tour they appear to have opened with the muscular Back in NYC from the Lamb album. It’s not an obvious choice, the song not having featured in the set since the Lamb tour; it’s also a throat shredder for Phil. It was quickly replaced by Deep in the Motherlode, one of their very best openers, with its dramatic keyboard riff and Phil’s emphatic call to “Go west, young man!”

“We’re going to play some old songs, and a few new songs, and some songs you won’t have heard for a long time,” announces Phil in Sheffield, almost word for word the formula that he had used on the previous tour, a formula that he was to continue using to the end. After Deep in the Motherlode comes a trio of well-established songs — a snippet of Dancing with the Moonlit Knight segueing into Carpet Crawlers, followed by the aforementioned Squonk (still in the set!) and then One for the Vine. All designed, one assumes, to placate longstanding fans. All cheered to the rafters.

The Cinema Show has gone … again … but will return … again. Gone, too, are Eleventh Earl of Mar and The Fountain of Salmacis, the early classic resurrected for the previous tour. Burning Rope and Ballad of Big from the previous album have also been dropped. For the North American leg, Carpet Crawlers and Say It’s Alright Joe are replaced by Misunderstanding, out as a single in the USA by that point.

The most eye-catching feature of the set is the placement of the new songs. Unlike on most tours, when new material is sprinkled liberally throughout the evening — on the previous tour it was done with almost mathematical precision — Duke is represented by a single block of songs.

Behind the Lines / Duchess / Guide Vocal / Turn It On Again / Duke’s Travels / Duke’s End

It is, in effect, the extended suite that was envisaged way back at the start of the Duke recording process when, according to Chapter and Verse, what became Turn It On Again was little more than a riff, a bridge between the two main blocks of ‘Duke’ music.

It is fascinating — and a joy — to hear it played in its entirety, particularly Duke’s Travels / Duke’s End, which didn’t feature on the following tour and was only resurrected (in part) for the 2007 Turn It On Again comeback tour, minus the vocals.

“Evening, chaps. Good to have you aboard,” says Wing Commander Collins to the Lyceum crowd. To watch Phil’s performance is to appreciate what an outstanding front man he had become by this point, as well as reinforcing how important he was to the Genesis live experience. It is not just that his voice, particularly his falsetto on the likes of One for the Vine, is now much stronger. Tony and Mike are relatively static and undemonstrative on stage; Daryl and Chester, as ‘extras’, are never going to claim the limelight. It is to Phil that our attention continually turns.

He is on sparkling form. This is still likeable Phil. Funny Phil. Hairy Phil. Not Armani Phil. We are up close and personal. To watch the video is also to appreciate the meaning of ‘intimate venue’. We see every gesture, every facial expression, every bead of sweat. At a time when his personal life is crumbling around him, it is an assured and compelling performance.

Storytelling remains a part of the Genesis show, as it has been since the early days. Phil’s one-liners are only marginally less humorous with the knowledge that much of it is scripted. We meet the character of Sidney, the drunk from Say It’s Alright Joe, complete with Columbo-style raincoat, whisky bottle and even a small table lamp perched on Tony’s keyboard. The routine comes across well enough in a smaller venue, but it is hard to envisage it working in somewhere like Madison Square Garden (hence the reason why it was dropped for the US tour, presumably). And, as on the last tour, The Lady Lies is another opportunity for some playful interaction with the crowd around a hero/villain narrative.

Laddish humour abounds (though in interviews Mike has commented more than once that as the hit singles increased so did the number of females in the audience). There is Roland the bisexual drum machine who plays with anybody. Juliet is no longer tied to the steering wheel; now it is Albert having sex with a television set. And there are silly puns aplenty referencing Albert’s cultural achievements: Romeo and Albert, Albert in Wonderland, Albert vs Kramer. ‘Albatross’ is a great shout from the audience, the heckler either exceptionally quick-witted or (perhaps more likely) someone seeing the show not for the first time.

Back to the music. Ripples is outstanding. Two tours in and Daryl is starting to capture Steve Hackett’s distinctively delicate and haunting sound, though it’s noticeable that the audience cheers for Chester are louder than those for Daryl. The interplay between guitar and keyboards is gorgeous, and there’s a deafening chorus of “Sail away, away” as the crowd join in. Next comes a breathless In the Cage, now segueing into the Slippermen keyboard solo, which is making its first appearance as part of an embryonic medley that ends with the glorious, soaring Afterglow.

After playing their biggest hit to date, Follow You Follow Me, proceedings conclude with the Dance on a Volcano / drum duet / Los Endos medley, followed by an encore of I Know What I Like (and occasionally The Knife — “This is the only other song we know”). It is a familiar way to close the show, complete with landing lights. But that’s fine. In fact, it is more than fine. It is magnificent. It is classic Genesis. The big commercial hits — the likes of Abacab, Mama and Invisible Touch — are in the future. No, the band were no longer writing songs like Supper’s Ready and The Cinema Show, but nor had they abandoned their roots.

Essential listening — and a great watch too.

As mentioned in the main article, there are some great recordings from this tour, principally Sheffield on 17 April and the London Lyceum on 6–7 May (and it seems that the Drury Lane show on 5 May was also recorded). The Lyceum shows were filmed by the BBC. A very watchable video of the entire show is in wide circulation, though only a 40-minute edit was ever broadcast, initially as an Old Grey Whistle Test special. The 6-CD/6-DVD box set Genesis 1976–1982 that was released in 2007 includes this footage.

There is a very listenable recording of the Madison Square Garden show on 29 June at the tail end of the US tour. It includes Back in NYC, which they played there as an additional encore.

The Genesis Archive 2 box set includes great-sounding live versions of Deep in the Motherlode (Drury Lane, 5 May), Ripples (Lyceum, 6 May), Duke’s Travels (Lyceum, 7 May) and The Lady Lies (Lyceum, 6 May). Duke’s Travels also includes Duke’s End, though this isn’t credited on the sleeve. One for the Vine, recorded at Drury Lane, was featured on the UK version of Three Sides Live.

Books, TV and Films, July 2020

1 July

Some thoughts, to begin with, on Philomena and On Chesil Beach, two films I watched last week on the BBC and thoroughly enjoyed.