Teenage Tales of Queen via Ten Objects

Memories, my memories

All Dead, All Dead (Brian May, 1977)

How long can you stay

To haunt my days

These reminiscences are neither comprehensive nor authoritative; still less do they amount to any kind of a history of Queen, ‘personal’ or otherwise. Rather, like the scrapbooks I used to lovingly fill, it is an attempt to glue down fading memories and slowly blurring mental snapshots and to capture odd — literally, in some cases — anecdotes of a somewhat obsessive schoolkid, all of them bound up in a variety of Queen-related items that I acquired over the years.

Much of what I talk about here occurred in my secondary school years from 1977 to 1982. Younger Queen fans reading this should remember that the 1970s were a distant land without YouTube, Spotify and BluRay, without MTV and VH1, without even home video machines. Radio 1 was transmitted on crackly medium wave in mono sound; Radio 2 was for old people. Quality rock music on the three — yes, three! — TV channels was virtually non-existent. Top of the Pops was an excruciating mime-fest and The Old Grey Whistle Test by the late-‘70s privileged Annie Nightingale and new wave over Whispering Bob’s ‘progressive’ rock. (Documentary footage of Queen shot by Whistle Test in autumn 1977 was, of course, never shown. There is footage on YouTube of Annie Nightingale talking on the telephone with Brian from America during the Jazz tour.) If you happened to miss what little was broadcast – well, tough.

Yet, despite it all, we survived! For those who were there, “these days are all gone now, but some things remain…”

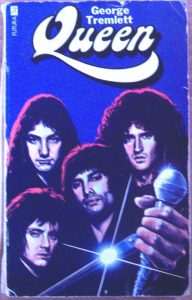

George Tremlett’s paperback was written in 1975 and published the following year. The final page offers a tantalising glimpse of the ‘new’ stage show, which opened with Bohemian Rhapsody, though the last entry in the appendix’s chronology of concerts lists two nights in Brisbane, 22–23 April 1976, one of which was presumably scheduled (hence its listing in the book) but does not appear actually to have taken place (at least according to my edition of Greg Brooks’ Queen Live).

Greedy for knowledge of my new heroes, I must have picked the book up sometime in 1977 or — more likely — 1978, in any case well before the advent of glossy, informative and comprehensive music magazines like Q. In the weekly music papers — principally NME, Sounds and Melody Maker — coverage of Queen was scarce, uninformative and, in the main, extremely hostile. Aside from the anodyne fan club biography, Tremlett was my introduction to the World of Queen.

The book is competently written and researched. Evidently, Tremlett enjoyed ready access to Brian’s parents and he quotes Brian’s father extensively; Freddie’s parents, Bomi and Jer Bulsara, by contrast, appear to have been much more guarded and unforthcoming (perhaps wishing to keep a low profile, mindful of widespread racial prejudice in 1970s England). The text adds a little colour to Brian’s oft-repeated statement — on the documentary Days of Our Lives, for example — that his father only really ‘got’ Queen after Brian flew his parents to Madison Square Garden (presumably in February 1977, Queen’s first show there. This is documented in Brian’s marvellous book, Queen in 3-D.) For example, though acknowledging the existence of family tensions, Harold May, speaking to the author probably in late-1975, says: “We still think that Queen II was a masterpiece.”

My copy is dog-eared and much-thumbed; its black-and-white photos were long ago sacrificed for display on my bedroom walls. A separate appendix reprints personal questionnaires completed by the band (date unspecified but the most contemporary reference appears to be Queen II, released in March 1974). Something of the band’s individual personalities is revealed here. Freddie lists his ‘special talent’ as “ponsing and poovery”, a singular turn of phrase reminiscent of the equally unforgettable ‘Bechstein Debauchery’. John’s ‘dream’ is “wet”. Unsurprisingly, Brian seems to have approached the task the most earnestly of the four. After thirty-plus years, I finally tackled The Glass Bead Game by Hermann Hesse (Brian’s ‘favourite book’) – an interesting and typically cerebral read, if somewhat dated now.

This badge reminds me of the time I first discovered Queen through school friends, even though it was probably purchased a year or so later. It’s an example of the sort of cheap, knock-off seaside fare that we bought as kids; the 1978 Jazz font is juxtaposed with a 1977 promotional image. Good Old-Fashioned Lover Boy started my singles collection (yes, I am aware that it’s actually an EP); A Day at the Races was my first album, possibly picked up on holiday in Llandudno during the Whitsun school holidays.

Albums were relatively expensive to buy in those days — about £4. As my mum was still sceptical about my interest in Queen, she took me round to her friend’s house one evening in October ’77; her friend’s son had a copy of the new album, News of the World, and I was allowed to listen to it in full (in another room) to check that I did actually like it. I remember nearly falling off the chair during the Sheer Heart Attack solo, worrying that the record player was faulty or that the needle had stuck.

Fellow-fanatic and school-friend Keith and I hatched a frankly ridiculous plan to enter the school Christmas talent competition and mime to We Are the Champions, Queen’s then-current single. Armed with a cassette tape player, an acoustic guitar, a genuine electric bass (minus amplifier or power lead) and a set of textbooks for drums (with real drumsticks, making all the difference), we cajoled friends Tommy and Shaun to join in — doubtless bribing them with 2oz of pear drops or the like. Bizarrely, we survived the ‘audition’ and then, foreshadowing Queen’s Live Aid triumph eight years later, stole the show on the night. I, by the way, was Freddie, an upside-down golf club substituting for the iconic microphone. Leotards, bangles and black nail varnish were mercifully absent. Looking back, I still feel a touch of guilt about the other entrants, who presumably had some genuine talent or other.

At the first years’ disco a few days later, Keith and I somehow coaxed the entire year group onto their hands and knees to hammer out We Will Rock You on the hall floor. An impressive sight, if somewhat odd — given that this now-iconic song had yet to find its place in the wider public consciousness and was, at that time, ‘merely’ a b-side. Six months later, when asked by the English teacher the title of my individual project, I proposed ‘Queen’. “But you ‘did’ Queen at the talent show and at the Christmas disco,” she protested wearily. How little she understood.

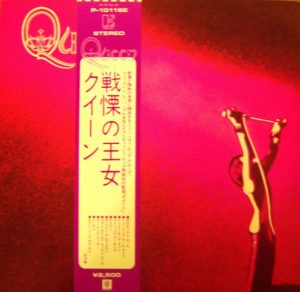

This Japanese import of the first album is, I think, one of the first ‘rarities’ I ever bought and still a favourite. Apart from the cost of the item itself, buying a rarity involved either a trip to the nearest city where record shops were much better stocked or an agonising ten-day wait for the cheque to clear, if buying by mail order from the back of Sounds. Imported Japanese singles and LPs — at hugely inflated prices — were quite the rage in the late-‘70s, with their reputation for quality and excellent packaging. Certainly, the vinyl felt thicker and less flimsy than the British equivalent, the cover was made of thick card and each release was presented with an exotic wraparound label (the Japanese lettering prominently displayed) and a thin plastic covering.

This particular item — the debut album — offered two additional attractions for me. Firstly, the distinctive red Elektra cover, quite different from the standard EMI version (Elektra was Queen’s record label in much of the non-European world in the ‘70s). Secondly, all Japanese LPs contained a lyric sheet – not included in the EMI release.

I have never been great at disentangling lyrics from the background music, and I was eager for clarification of some of the words, phrases and lines that I had always struggled to decipher on the first album (My Fairy King is the obvious example). Alas, I had failed to factor in the somewhat limited abilities of the translator. For example: “Gonna blast it around / This music’s gonna make you a star / Girl’s in your arms and she gassed / And you should go far…” is supposedly from the final verse of Modern Times Rock ‘n’ Roll.

For years I struggled to nail down the precise wording of Freddie’s follow-up to Roger’s line “Do you think you’re better every day?” in Keep Yourself Alive. Our Japanese wordsmith came up with: “No, I just think all roads just lead right into my grave”. My 1994 Digital Master Series CD booklet, on the other hand, renders it thus: “I just think I’m two steps nearer to my grave”. One of my favourite Queen ironies is that Keep Yourself Alive, a live staple, was always performed towards the end of the set as a rousing, get-’em-out-of-their-seats, celebration of life; the meaning behind Brian’s lyrics is undoubtedly much darker.

This sew-on badge was, I think, a renewal gift from the fan club. I first joined in spring ’78 so it’s probably from 1979 or perhaps 1980. Sadly, I have very little memorabilia left from my years in the fan club. Just like the photos in Tremlett’s book, the quarterly magazines were mercilessly pillaged to decorate my bedroom (alongside the nude bicycle race poster from Jazz, which mum inexplicably allowed me to display). The tour programmes from 1978, 1979 (my favourite) and 1980 all met a similar fate. Insane acts of vandalism, when I reflect back, but this was twenty-five years or more before eBay. Besides, what does an acne-dotted thirteen-year-old understand of nostalgia?

Each member of the band wrote an annual letter for the fan club magazine. (Some of the letters are reproduced in the book accompanying the News of the World fortieth anniversary box set.) Freddie’s letters were always light and gossipy — buying a new piano, taking up smoking. I have no recollection of John’s, to be honest (humble apologies, John). I do, however, recall my frustration at Roger’s autumn ’78 contribution because he wasted precious space listing the tracks on the forthcoming album (Jazz). He also judged it to be their “best” yet. I doubt he or posterity now agrees. Brian’s contributions were densely packed and scrawled like a doctor’s prescription.

I somehow deciphered Brian’s all-but-illegible handwriting in the spring 1981 magazine, in which he proudly announced the release of the film Flash Gordon (music by Queen, of course) — “I managed to get in there and turn the music up”, or words to that effect. I think it was the spring ’81 issue at any rate: the winter ’80 issue was definitely a special picture-only colour issue.

What lingers in my mind, however, is Brian’s heartfelt plea to us fans not to attend the screening if our local cinema had yet to install state-of-the-art stereo sound. I live in Wigan, not Leicester Square; Wiganers are pioneers of pie-eating, not new technology. Do I choose the rock (no pun intended) or the hard place — boycott brand-new Queen music or snub the wishes of Brian May? Yikes! I confess I chose the latter. Brian, I can only beg your forgiveness. I wonder, is this a good time to admit that I’ve never seen We Will Rock You?

This Jazz lyric sheet was a freebie sent to all fan club members in late-’78 after the release of the Jazz album, the first one not to include printed lyrics since their debut. Four individual portraits adorn the reverse. Brian looks pensive (nothing new there), as does Freddie; perhaps he is still dreaming of the Tour de France (which allegedly inspired him to write Bicycle Race when it passed close by their recording studio in Montreux). Roger holds a cigarette defiantly aloft; John sports his severe ‘skinhead’ haircut. The excellent Queen Live website dates Freddie’s shot to a press conference held the day after the infamous New Orleans party on 31 October 1978. It always puzzled me that they didn’t print the lyrics to Mustapha and I still can’t follow the words of Bicycle Race in print without being convinced by the end of the song that ‘bicycle’ is spelt incorrectly. Try it.

Within months of Jazz, Queen Live Killers was available; I was, by this time, a teenager and spending hours secreted in my bedroom. However, while normal lads thumbed girlie magazines or girlie bra-straps, I was using an old walking stick to mime Brian’s guitar parts (swapped for a tennis racquet during the acoustic set). A toy cannon perched perilously on a pile of Beano annuals doubled as a microphone for Roger’s vocals (more substantial vocal parts than Brian’s, I always thought). Silly, silly, silly. Or was I subconsciously revisiting Tim Staffell’s stories of Freddie miming to Jimi Hendrix with a twelve-inch ruler in the art room at Ealing College that I’d lapped up from reading Tremlett?

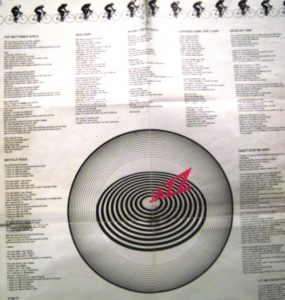

The picture from the Another One Bites the Dust picture sleeve is, of course, a still from the Play the Game video, released in mid-1980. Back then, the only way to be sure of seeing a video was on Top of the Pops. This shot prompts the memory of a strike in the summer of 1980 (either at the BBC or by the Musicians’ Union or Equity; I forget which). TOTP was off air, a casualty of the strike, and I only caught the video once — perhaps on ITV’s Tiswas. I was devastated. For all I knew, it might never be broadcast in public again, thus demonstrating complete ignorance of the fact that the world was about to embark on an incredible technological and communications revolution. Within three years, my parents had bought our first home video machine and I was able to watch (and watch again … and again) Queen’s Greatest Flix, a sixty-minute tape of the band’s music videos, available at the press of a button. How lucky I felt.

Speaking of Tiswas (a raucous, groundbreaking, Saturday morning show aimed at kids but probably watched by as many adults, especially dads), I remember Roger and John making a guest appearance at the time of the Crazy Tour in ’79, offering a gold disc as a competition prize. The question was to name the two Marx Brothers’ films used as Queen album titles. Answers on a postcard. I duly sent off my entry, cleverly adding (or so I thought) that Duck Soup was also the title of a Queen bootleg. I didn’t win.

Back to technology. I am reminded of dragging mum round town, hours before a long, boring coach journey to France during Easter 1981, scouring the high street for a curious item Roger was photographed holding in the 1980 tour programme. Wigan’s electrical retailers were collectively baffled by my description — why didn’t I take the photo, I wonder? And yet, by the following Christmas, a ‘Walkman’ (the mysterious item in question) was the must-have accessory for any teenage fan of music. Maybe Roger had picked his up on the 1980 US tour, itself a reminder of how far so-called ‘advanced’ Britain lagged technologically behind other parts of the world, notably Japan and the USA.

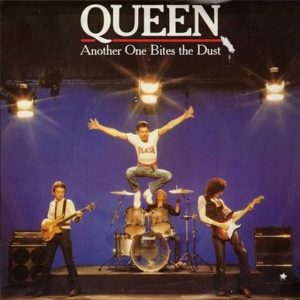

Of the myriad images taken of Queen over the years — with the tag ‘previously unseen’ increasingly the rule rather than the exception — why does this remain my favourite photograph of the band (well, of Freddie, to be precise)? For me, it captures quintessential ‘Queen’. Freddie’s mesmerising pose exudes pomp, grandeur and theatricality and endows the photograph with a symmetrical, choreographed quality, demonstrating an astonishing mastery of stagecraft. I adore the concert lighting from the mid-‘70s and remain baffled as to why the magnificent Hyde Park footage has never been cleaned up and officially released. (One song, Sweet Lady, is now officially available.)

The photograph also represents my favourite era of Queen (roughly ’74–‘76) and — heresy, I admit — for me, Lap of the Gods was always a more exhilarating set-closer than Champions. Yes, I realise that Champions was actually the final encore, but you get my drift. Later-era Freddie was a showman, an entertainer, captivating and charismatic, to be sure. But this is early-era Freddie: camp and fey, yet majestic and arrogant. Incidentally, why, I ask myself, are dry ice and flash-bombs so under-used on stage these days? Are they disparaged, perhaps, as ‘70s-era kitsch? (Dry ice was used on the Queen + Adam Lambert tours, for example during I’m in Love with My Car in 2017. I asked one of the stage production team about the absence of flash-bombs in recent times but didn’t get a particularly revealing reply.)

This is the front page of one of many Queen lists and ‘biographies’ I wrote through my teenage years. The font comes from The Game, simply because I found it the easiest to copy. Note the mock-serious use of the ‘Published’ symbol and date, as if this were some sort of official publication. I was obsessed with writing histories of Queen (I taught history for many years — is there a connection, I wonder?).

My schoolboy efforts shamelessly plagiarised information (and not a few clichés) gleaned from Tremlett and a similar paperback written by Larry Pryce, as well as the fan club magazines, of course. These biographies were painstakingly ‘illustrated’, another home for many of my cut-out magazine photos. It certainly helped me acquire an encyclopaedic knowledge of the concert venues of the UK and USA, not to mention the catalogue numbers of all single and album releases up to Hot Space, after the release of which it became rather predictable: ‘Queen1’ (the catalogue number of Radio Ga Ga), ‘Queen2’ etc spoiled the fun somewhat.

Unlike many record labels, EMI (was it their decision?) omitted song timings on record labels or sleeves. As a result, a particularly diverting (‘geekish’, some would say) activity was to use the stopwatch facility on my then-new digital watch to time the length of each track. As a Genesis, Led Zeppelin and Yes fan too, it irked me that Queen never indulged (a very ‘Roger’ word) in long, drawn-out epics. By the by, a consequence of this innocent pastime is that my collection of original picture sleeves is now virtually worthless. With one carefree wave of my biro, I forever disfigured them by inscribing the a-side and b-side timings in a suitably prominent position. No matter.

I agonised over the ‘true’ length of segued songs such as Flick of the Wrist, Love of My Life and Teo Torriatte. Sadly, EMI’s experts do not appear to have been similarly exercised in the run-up to the initial release of Queen’s back catalogue on CD. Faulty indexing/mastering of Queen II resulted in the final verse of The March of the Black Queen being tacked on to the beginning of Funny How Love Is. An egregious error for any fan.

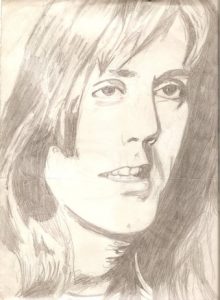

This sketch dates from 1979, I think. My dad was talented at drawing and painting. He used to spend hours helping me with my art homework, teaching me about the ‘vanishing point’, perspective and light and shade. He produced fantastic pencil drawings of Brian, first at Hyde Park or more likely from the gig at Edinburgh a couple of weeks earlier – it was the image of him in the gatefold sleeve of the A Day at the Races album playing ’39 – and then on the Jazz tour, making ingenious use of the shapes in (I think) a razor-blade accessory to help him re-create the ‘pizza-oven’ roof of lights. After copying cartoon figures and caricatures, ‘Roger’ was my first effort at drawing a human face.

Image-wise, Roger was my favourite as a teenager, obsessed as I was with his immaculate white teeth and flowing blond hair (before he had it all cut off, around the time of the British shows in May/June 1977). Frustrating battles with mum over the length of my hair — usually the Friday before the start of the new school term — loomed over my teenage years and defined the limits of my adolescent rebelliousness. I always lost. Meanwhile, Brian’s musical sensibilities and extraordinary efforts at the cutting edge of astrophysics, stereo photography and animal welfare long ago secured his promotion to ‘favourite band member’ status. Besides, he and I share a birthday (the date, not the year). So there.

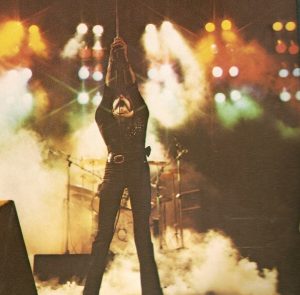

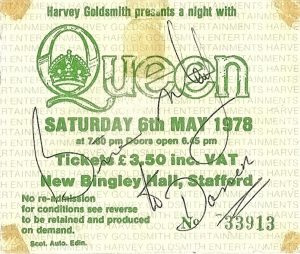

I wonder what you regard as most valuable Queen possession. For me, it is a simple piece of paper: the ticket stub for my first ever Queen concert, which was Stafford Bingley Hall on 6 May 1978 during the News of the World European tour. Re-reading set lists and hearing recordings from the tour, I confess that virtually nothing of the concert itself has stuck in the memory. According to Queen Live, the band performed the standard set list. Perhaps I was just too young. Memories of my second gig — the Liverpool Empire, 6 December 1979, on the Crazy Tour — are much more vivid.

I have just two recollections of the Bingley concert. First, as a highly self-conscious eleven-year-old, I stupidly decided not to wear my glasses and so, standing at the back of the venue, saw virtually nothing except a myopic blur. Magnificent crown lighting rig? What magnificent crown lighting rig?! (I have since learned that only the lights were used at Bingley Hall and not the whole crown rig because of the size of the venue.)

Second, the volume. As a kid of the mid-‘70s, music meant a transistor radio, a record player (or music centre, if money permitted) and the occasional disco in a large, echo-filled room. None of this had prepared me for Queen’s assault on the senses. I still half-jest to friends about the ‘ten’ minutes it took to disentangle actual music from the ear-splitting din that washed over me like a tsunami.

After the show, Keith and I wrote letters to the band via the fan club. I enclosed my ticket in my letter to Brian and waited. And waited. One day, weeks — or perhaps months — later, a ‘Queen’ envelope arrived, addressed in Brian’s unmistakeable hand and enclosing the aforementioned ticket, duly signed. Priceless.

A version of this article was first published as a ‘fan feature’ on the official Queen website in August 2012. Most of the comments in round or square brackets relate to information that has come to light in the intervening six years.

Brilliant recollections – everyone a personal memory. As you say – priceless – Ed (loserintheend)

Many thanks – it was a joy to write. Your tweet of the old fan club biography was a real trip down memory lane.

very interesting. Reminds us older fans how obsessed we were in those early days.