Books, TV and Films, August 2020

1 August

With the football season at an end, there’s time to try out a classic film that I have never actually seen before — Ice Station Zebra — ‘classic’ in the very loose sense of a film with an all-star cast that turns up quite a lot on television. It came out in 1968 and is based on a novel by a famous thriller writer of the day, Alistair MacLean. I have only ever read one of his books, I think (Partisans, a book-club buy from the early-’80s), but I automatically place him in the same bracket as Jack Higgins — exciting, page-turning plots let down by unexciting, predictable and poorly drawn characters — whose books (the most famous is probably The Eagle Has Landed) I am a bit more familiar with.

Ice Station Zebra is set during the Cold War, but it has the feel of many of the Second World War movies that were popular in the sixties — the likes of The Dirty Dozen and Where Eagles Dare (which is also by MacLean). Watch any of the above and expect secret orders passed down from on high, plenty of suspense interspersed with bursts of derring-do, clean-cut heroes and dastardly villains, courage and betrayal, few if any women, and lots of cigarette smoking.

Life inside the submarine is suitably claustrophobic and, like Where Eagles Dare, the film features stunning location photography, though the scenes at the Zebra station on the polar ice-cap are poorly realised in comparison. Rock Hudson is the cool-under-pressure captain, Ernest Borgnine struggles to convince with his dodgy Russian backstory and even dodgier accent, and Patrick McGoohan plays a secretive (and, stretching it quite a bit, vicious) spook to type: it could be the exact same agent as the one he portrayed in a Columbo episode a few years later (Identity Crisis, the one in which he kills Leslie Nielsen).

2 August

More television (well, Amazon Prime). This time, Knives Out. I wasn’t too sure what to expect; my guess, based on media advertising, was some kind of ingeniously plotted farce or spoof. Actually, it is more like an homage and didn’t disappoint.

Once I got over Daniel Craig’s southern drawl (at first I thought his voice was badly overdubbed) there was much to enjoy, even if it was a bit silly in places — the suspect who is unable to lie without immediately vomiting, for example. It borrowed ingredients freely (though respectfully) from the Agatha Christie recipe — the labyrinthine house; the sudden and suspicious death of a wealthy patriarch; the family squabbling over the will; the everybody-is-a-suspect-and-has-a-shaky-alibi routine etc.

All very 1930s. In one respect, however, Knives Out seems to be making a very up-to-the-minute political statement. The family members — white, wealthy, privileged — are greedy, duplicitous and self-serving. They each make a show of welcoming the Latina nurse into their family and their home, but it is all pretence (their lies exposed when she unexpectedly receives the bulk of the fortune of the deceased patriarch). It is the nurse who, throughout, is the one genuine, kind and likeable character, determined to do the right thing. It’s hard not to see it as a commentary on the Trump administration and the state of US politics.

6 August

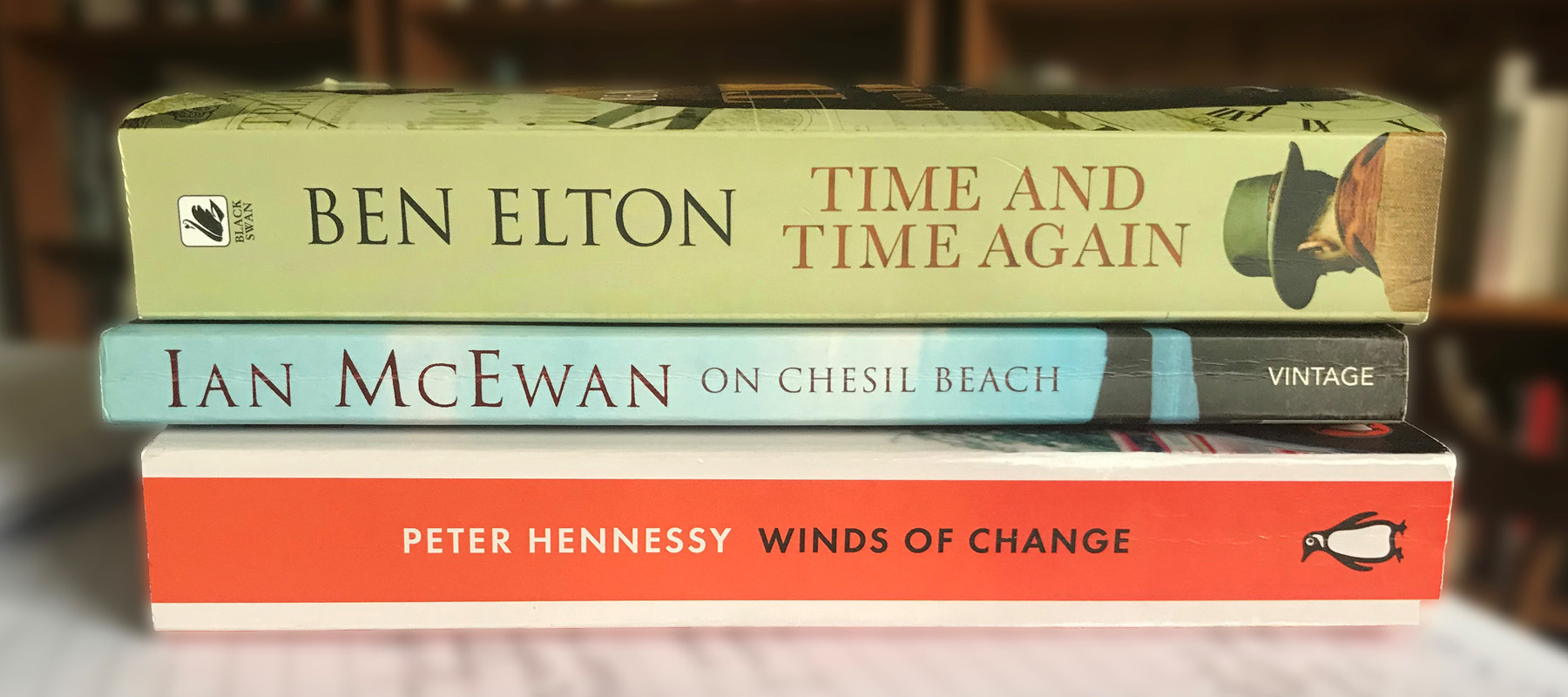

I had to re-read On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan, having watched the film a few weeks ago. At just 160 or so pages it’s really a novella. It’s quite extraordinary how McEwan is able to say so much in so few words.

A million years ago, sitting my A-level general studies exam, I answered an essay question that basically asked us to consider whether film adaptations of books can ever do justice to the original text. I was reading a lot of Sherlock Holmes at the time and, if memory serves, based much of my answer around a discussion of the Basil Rathbone/Nigel Bruce films. I imagine I focused on the difficulty films have in exploring the inner voice (though it’s doubtful I used quite those words).

Films do narrative well. Sometimes — as in the ending of Stephen King’s The Dead Zone — they improve on the original text. But they have a harder task than books at exploring character in a nuanced way. Not the stock ‘goodies’ and ‘baddies’. That’s all too easy. Nor do I really mean the Bildungsroman-style character arc in which a person undergoes some sort of metamorphosis over the course of the film. I am thinking more about finding a way to portray the jumble of sometimes contradictory feelings, moods, emotions and urges that most of us feel most of the time. How to portray someone like Florence Ponting from On Chesil Beach, for example.

12 August

Being in a ‘horror’ frame of mind after just writing the first part of my blog on Dennis Wheatley, I decided to watch Interview with the Vampire. It came out in 1994, but I have never see it before. I won’t be in a hurry to watch it again any time soon. I know that the Anne Rice novel, which I haven’t read, was hugely popular but I found the film — and the performances of Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt — less than enthralling.

Perhaps it was trying too hard to be sophisticated. Much more to my liking was Lust for a Vampire, shown on a cable channel the other day. It’s typical of those classic Hammer productions that don’t take themselves too seriously. Predictable plot. Stage-y sets. Generous helpings of tomato-ketchup blood. Dodgy overdubbing. And happy-go-lucky, nubile serving girls who speak perfect English despite the central European location and who think nothing of going off alone despite a number of unexplained deaths in the local area of other happy-go-lucky, nubile serving girls.

Scars of Dracula (starring a very young Dennis Waterman and Jenny Hanley), released in 1970, is rather tame, but in a sign of changing times Hammer upped the sex quotient for its Karnstein trilogy: Lust for a Vampire, The Vampire Lovers and Twins of Evil all feature more than a hint of lesbianism and scenes of not-exactly-central-to-the-plot female (mainly) upper-body nudity.

It’s all harmless stuff — the most explicit thing about them are the original promotional posters — and quite ridiculous that films like these still seem to be rated 18.

13 August

After Robert Harris’s brilliant The Second Sleep, here’s another treat, bought on the day it came out in paperback: Winds of Change, the latest volume in Peter Hennessy’s postwar history of Britain, this time covering the early sixties.

I don’t watch a huge amount of television and I am conscious of having missed out on loads of great programmes over the years. When the lockdown first kicked in, I decided to try out something from BBC iPlayer. As a fan of the spy genre I settled on Spooks. Ten series. Eighty-odd hour-long episodes. Enough to keep anyone busy. I finally finished it this week.

A big surprise — I have only just found this out after looking up Spooks on Wikipedia — is that it was a production-company and not a BBC decision to end the programme. That’s quite refreshing. Even allowing for the fact that I was watching it over a relatively short span of time, it felt by series 10 like enough was enough. Another episode; another day in Spookworld. Another terrorist outrage averted here; another corrupt top-level appointee or politician unmasked there. Another intelligence agency up to no good here (take your pick — the CIA, the FSB, Mossad); another dodgy organisation with global tentacles up to no good there (the slightly preposterously named ‘Yalta’, for example).

It was smart. It was sexy. It was tech-y. It was exciting. Was it also a little too predictable? As soon as it was revealed in series 10 that new spook Erin Watts had a young child, it surely wouldn’t be long before the said child was kidnapped or murdered by bad guys. And indeed it wasn’t.

Somewhat predictable, then … except in one regard: the death rate among lead characters. Everybody was expendable. Nobody, but nobody (except Harry), was exempt, and not just in end-of-series cliffhangers either — from Helen in the second episode of series one to Danny, Zaf, Adam Carter’s wife, Adam Carter himself, and finally (the saddest one of all) Ruth. It’s a long, long list.

20 August

Peter Hennessy’s Winds of Change is excellent. No surprises there. I first discovered Hennessy via a work colleague who had been an undergraduate student of his at Queen Mary’s in London and spoke of him in reverential terms. I read Whitehall, his huge book about the history and inner workings of the civil service. He is a trusty guide and absolutely authoritative. He is a capable broadcaster, too; his is the voice I always listen out for as his media role as both ‘talking head’ and presenter has flourished over the last couple of decades.

In the preface to the first volume of his history of postwar Britain, Never Again, published in 1992 and covering the Attlee government, Hennessy refers to a project spanning the years from 1945 to 2000. Plans obviously changed. There has been at least a decade between each volume. The second, Having It So Good, encompasses the whole of the fifties. This volume covers only the years 1960 to 1964 but much of the media comment surrounding the book’s launch is of it completing a ‘trilogy’.

It is little surprise that Hennessy became a go-to academic for expert, objective analysis. As well as having encyclopaedic knowledge, he is also at ease in front of a microphone. And he writes like he talks, mixing magisterial insights with gossipy asides. “Poor Selwyn!”; “Very Rab.”

It helps that he has interviewed pretty much everybody that matters in British politics over the years. Liberal use of ‘private information’, often in footnotes and end-notes, combined with recently declassified documents and unpublished minutes of key meetings reinforces the sense as you read Hennessy that you are being offered privileged access to little-known, hush-hush stuff.

Hennessy specialises in what he calls the ‘hidden wiring’, the workings of government not ordinarily in the public gaze. This at times leads him to focus on such matters at the expense of other areas of importance and interest. For example, we return repeatedly to official (and top-secret) preparations for government in the event of a Soviet nuclear attack. Okay, but this reader at least would have expected in a history of sixties Britain a bit more than we get on social and cultural developments.

Hennessy has a keen sense of the absurd and the quirky; there’s half a page devoted, for example, to Selwyn Lloyd’s dog, Sambo. More often than not, such you-couldn’t-make-it-up stories — as in the extraordinary arrangements for the prime minister to use the AA roadside-phone network to contact the Number 10 switchboard in the event of a nuclear attack taking place when he was away from London — tell us something rather revealing about the state of Britain at that time.

I watched Lady Bird, another hugely enjoyable film starring the excellent Saoirse Ronan. It has a similar coming-of-age, teenage-angst theme as On Chesil Beach, though ultimately it’s less dark. It’s a tale of two strong-willed women — a mother and her daughter — and of things left unsaid.

24 August

I knew that after reading The Second Sleep I had to go back and re-read Ben Elton’s Time and Time Again, another novel that plays around with history. I think I have read everything by Ben Elton, ever since his first novel Stark had me laughing out loud thirty or so years ago. For a long time he specialised in satirising whatever was the latest pop-culture obsession — drugs, talent shows, Big Brother-style fly-on-the-wall TV. Some of his books I enjoyed more than others. I loved Blast from the Past, but Inconceivable was less good. Some of his later efforts have been more historical — The First Casualty (the First World War) and Two Brothers (Nazi Germany).

This time around (no joke intended — the book concerns going back in time) the predictability of the characters in Time and Time Again grated a little. They are all larger than life, versions of Elton himself in a way. Hugh ‘Guts’ Stanton is the biggest, baddest ‘survivalist’ soldier around. Bernadette Burdette is the beautiful, loquacious free spirit he meets on a central European train, her every thought and utterance typical of the 2010s rather than the 1910s. Least believable of all is the foul-mouthed distinguished professor of history at Cambridge University who seems to think like a Sun editorial. Okay as a one-off maybe but then we meet the Lucian Professor of Mathematics, an “appalling media tart” who wears a ‘Science Rocks’ badge and says things like “Why in the blinking blazes was old Isaac getting his knickers in a twist?” Old Isaac being Sir Isaac Newton.

Nevertheless, one thing that Elton does brilliantly is plot. He is astonishingly imaginative, and although the basic set-up here is familiar — travelling back in time to change the past and therefore the future — Elton packs it with plenty of twists and turns. One, in particular, had me gasping (on p441 of the paperback). Nicely done, sir. I also liked the fact that the infamous assassination in Sarajevo happens (or rather, doesn’t happen) halfway through the book, allowing Elton to have plenty of fun with counterfactual histories.

Your Alistair MacLean post reminded me of my first venture into reading sea novels as a child reading HMS Ulysses by Alistair MacLean, based on his experiences in the Royal Navy during World War II. HMS Ulysses story relives convoy duty in the freezing and inclement North Atlantic weather, mountainous waves and the ever present threat of U-boat attach, and how the sailors had to wear gloves to stop their hands sticking to the cold metal ship’s handrails. HMS Ulysses started my sea novel odyssey, reading some 20+ books following the fortunes of Hornblower (C.S. Forester), a navel officer in the period of the Napoleonic Wars; The Captain Bolitho series, Bolitho serving in the wars against France (Napoleonic period again) and the United States (Douglas Reeman under the pseudonym Alexander Kent) and the English naval captain’s (Jack Aubrey) adventures – some 14 novels – with his Irish-Catalan friend Maturin (Napoleonic period once more) by Patrick O’Brian. The other stand out novels along with HMS Ulysses: Joseph Conrad’s ‘Typhoon’ stands out for the sheer ferocity of the weather. The second – ‘The Death Ship’ for its portrayal of sailors devoid of passports and identity papers – in effect stateless, anonymous nobodies. The story is centred on two of the sailors who work out that the ship is to be scuttled for insurance purposes. The captain and co-conspirators are set to abandon the ship leaving the crew to drown – hence the title, ‘The Death Ship’. They say sea novels provide the best opportunity to explore the human condition. The novel setting has clear boundaries – the ship itself – leaving the action and the characters to play out the drama. Sometimes it’s the environment itself, at other times it’s the characters, and often it is a combination of both making for gripping reading.

Hi there. Many thanks for taking the time to reply. I am glad that my blog brought back a few fond memories for you. Novels about the sea have never really appealed to me, maybe because nothing captured my imagination as a young reader like MacLean did for you, maybe because I am not a good traveller and I get seasick easily. Moby-Dick (if that counts) is one of the many ‘classics’ that is destined to remained unread. Ditto Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.

Stephen Fry tells a funny story about Hornblower in volume two of his memoirs, but it’s too rude for a respectable website like this. [It’s on page 177 of the hardback edition]