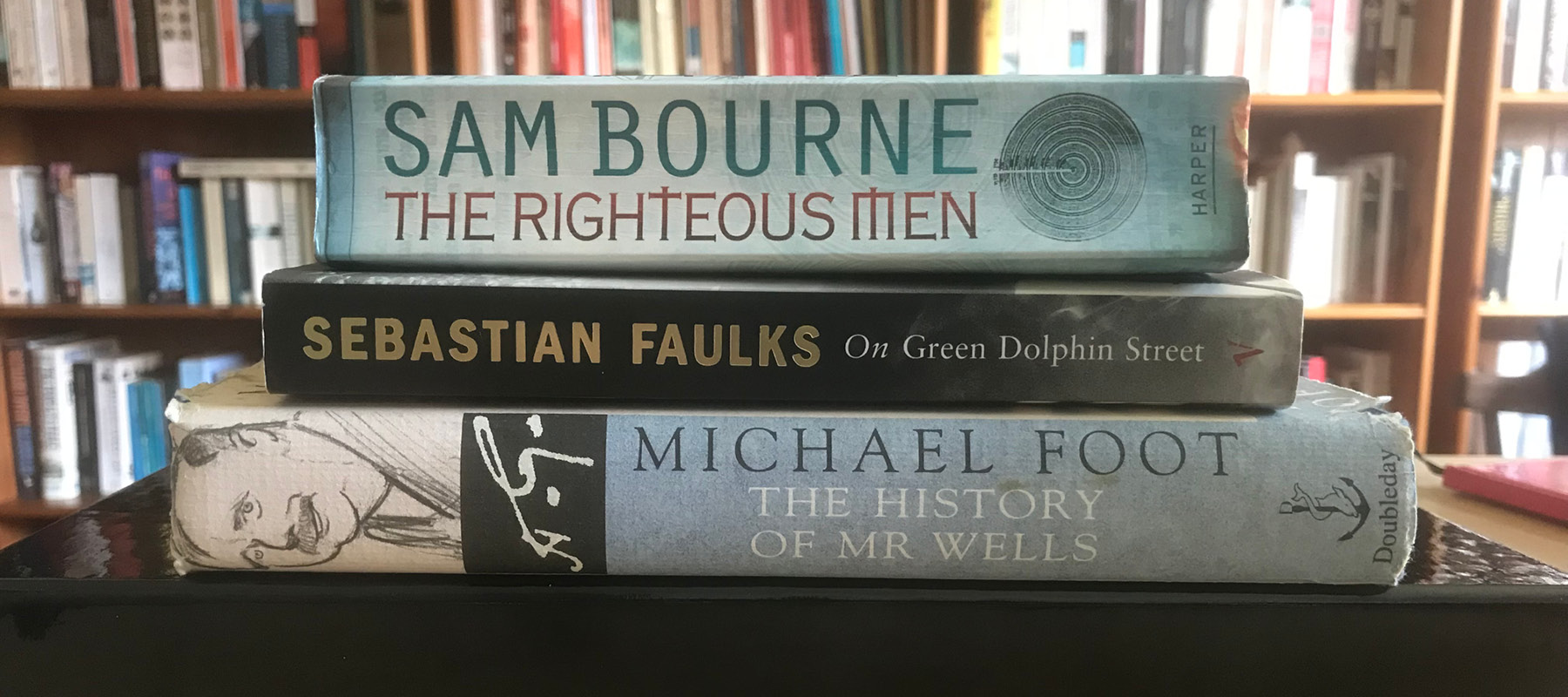

Books, TV and Films, March 2020

3 March

Back to one of my favourite novelists — Sebastian Faulks. Birdsong is probably his best-known book, but my favourite is Human Traces, a brilliant mix of invention, imaginative reconstruction and exposition of developments in psychiatry and psychoanalysis.

I have reached for On Green Dolphin Street, not a novel I have read before. In fact, when I opened the book at page one, I knew nothing about it whatsoever, except that it was set in the United States some time after the Second World War.

It’s a great feeling, reading from one page to the next with no idea about who the characters are, how the story will develop or even what the book is actually about. Early indications are that it involves a clever, fast-tracked diplomat whose career has stalled and whose problems are slowly but surely grinding him down, and his relationship with his devoted wife, who appears to have a gaping emotional hole in her life.

One sentence has baffled me, and I can’t work out whether it’s an error. Mary, the wife, is conflicted:

She could not establish an order of preference between the two; as well ask her to distinguish between a tree and a cloud: no crude ranking could reflect the reality of either.

8 March

I’m two-thirds of the way through On Green Dolphin Street. It’s another Faulks treat. He is a master at conjuring up a sense of time and place — be it the trenches of the Western Front, Occupied France during the Second World War or, in this case, New York at the end of the ’50s and beginning of the ’60s. Faulks is also a wonderful crafter of stories, adding layer upon layer as he goes and weaving threads of context and background that combine to form a convincing picture of the characters and their lives.

All the signature Faulks traits are here: the background research is thorough, time and place compellingly drawn and the attention to detail remarkable. It’s a whirlwind tour of delis and diners, apartment blocks and shops, bars and nightclubs — all to a backdrop of jazz (On Green Dolphin Street is apparently a Miles Davis classic).

9 March

Wonderful. Just wonderful.

On Green Dolphin Street is much more than just a conventional love story. It explores the different types of loving relationships — the unconditional love between parent and child; that life-changing first love; the love that grows and develops between lifelong partners; passionate and erotically charged love; and love between two soul mates.

The busy, bustling, labryinthine streets of New York are wonderfully drawn. Faulks is perhaps using the city as a metaphor — both its bewildering complexity and its dazzling possibilities. The Second World War is also a lingering presence, casting its long shadow years after the war itself is formally at an end.

After briefly worrying that the ending was turning into a rerun of the final episode of Friends, I found the conclusion satisfactorily unsatisfactory. It was, after all, an impossible dilemma that Mary faced.

A must-read.

15 March

I am in the middle of recording yet another version of The War of the Worlds. I have always loved the original Gene Barry film from the ’50s, didn’t really like the Tom Cruise version and avoided the 2019 three-part BBC mini-series. This is a multi-parter and stars Gabriel Byrne. As with all multi-part dramas, I will watch it when all the episodes have been shown.

That reminded me that I haven’t actually read anything by HG Wells, except for the rather intimidating opening page of The Time Machine — at least, it seemed intimidating when I was a teenager. In the meantime, I have reached for H.G.: The History of Mr Wells by former Labour leader Michael Foot.

I have a lot of time for Foot. Whatever one thinks of his politics, he is a great writer and his two-volume biography of Nye Bevan was a big part of my formative years. The Wells book is something else — more a literary biography, perhaps even literary criticism, rather than a conventional biography. I am fairly certain, for example, that at no point does the book say what H.G. actually stands for. Another extraordinary feature of the book is the length of some of the extracts from Wells’ writing — an extract from The Passionate Friends, for example, stretches for nine pages.

19 March

I finished the HG Wells biography today. Two immediate thoughts.

Firstly, how little I knew about him. I was aware that he had written a number of sci-fi classics (I could probably have named about five) and, of course, I knew that he was a socialist. Little did I know of the prodigious output that he kept up throughout his life. Nor did I know anything of his rather colourful life, particularly his many sexual relationships.

Secondly, it has not been a particularly easy read, taking a great deal of knowledge for granted. I was on solid ground with the history and politics stuff, but the many, many literary references were often new to me and not always easy to follow. Making a regular appearance throughout the book were Wells’ literary hero Jonathan Swift — someone I definitely need to learn more about — and, to a lesser extent, other literary figures such as Lawrence Sterne, William Hazlitt, George Bernard Shaw, James Joyce and (of course) George Orwell.

In conclusion, this is certainly not a book for someone looking for an introduction to Wells’ work.

28 March

After struggling through the Wells biography, I was looking for something to really carry me away. The Righteous Men by Sam Bourne did not disappoint. It’s a long-ish read —560 pages or so. I more or less kept to my 10% daily target except for the end. A sure sign of a gripping read, I finished off the last 100 or so pages in a day.

Sam Bourne is the nom de plume of Jonathan Freedland, my favourite Guardian columnist. I read and enjoyed The Last Testament a few months ago. He has a new book out — To Kill a Man — but I like to be systematic so I went for this one, his debut novel, published in 2006.

At least one of the ‘puffs’ — the endorsement quotes on the front and/or back cover — compares him to Dan Brown. Having only seen the films, I can’t comment on Brown’s writing, but he will do well to match Bourne/Freedland, whose books are pacy, gripping and superbly crafted. In The Righteous Men, a mass of what the reader assumes to be minor detail, there to add colour or to flesh out a character’s backstory, is liberally sprinkled throughout the opening pages, only to take on huge significance as the plot unfolds.

Both of the Sam Bourne books I have so far read have had religion at the heart of the plot. Each has been exceptionally well-researched, delving into ancient beliefs and traditions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Each one raises interesting and important questions about the nature of religious faith and about religious fanaticism. I will say no more!

The Righteous Men has certainly whetted my appetite for my next read, John Barton’s highly acclaimed A History of the Bible.