Books, TV and Films, September 2020

2 September

I re-watched The Ninth Gate, having referred to it in my recent Dennis Wheatley blog. Considering that it is directed by Roman Polanski — highly renowned, if controversial for non-film reasons; my favourite film of his is The Pianist — it plods quite a bit and the special effects aren’t up to much (the mysterious guardian angel’s ‘flying’ sequences are woefully bad). In a sentence, I much prefer the individual ingredients — antiquarian books, mysterious codes for summoning the devil etc — to the finished meal.

I have also watched Joker. I am not into the Marvel/DC stuff at all and haven’t seen any of the many ‘modern’ Batman films except the very first one with Michael Keaton (in which Jack Nicholson played the Joker). Does Joker even count as a ‘Batman’ film? I saw it as a searing indictment of the way American society deals with mental illness and its poor and downtrodden more generally.

4 September

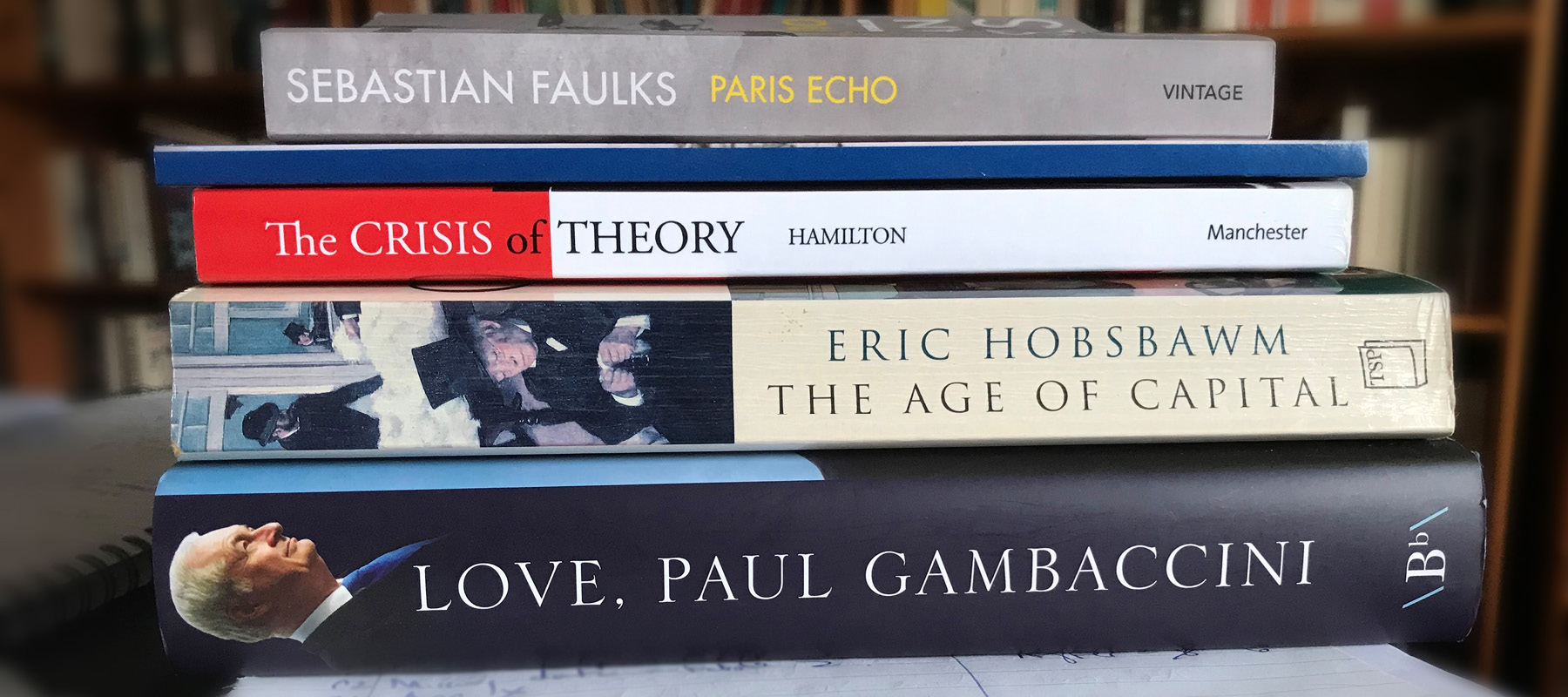

A book that has been on my must-read list for quite some time is Love, Paul Gambaccini, the DJ’s account of his year under arrest as part of Operation Yewtree, the police’s investigation into allegations of sexual conduct among ‘celebrities’ and other assorted VIPs in the aftermath of the Jimmy Savile revelations.

It is basically Gambaccini’s edited diaries for the year. As he himself says, if the police are going to arrest a journalist, they shouldn’t be surprised if the journalist keeps a journal. What happened to Gambaccini is shocking, and the book is a very uncomfortable read. You could put it down after a hundred pages without missing a great deal because Gambaccini’s life was basically put on hold for a year, despite the fact that he was never charged.

After his arrest it was like he was caught in a temporal loop. D-Day was roughly two months or so down the line, the date on which the police would inform him whether or not he would actually be charged. In those two months, as well as constant speculation on snippets of information gleaned from the police and other sources, there is much support from family and friends, many outbursts of anger, much cold shouldering and lots of eating out. Behind it all is a general build-up of tension as D-Day approaches. Then: complete anti-climax, as he is blithely informed that he is being rebailed for another few weeks. And so the cycle repeats. This nightmare went on for a year.

Gambaccini worries on 8 August: “What if the book I am writing is also met with a national yawn?” If so, that would be a shame because this is an important book, one that needs to be widely read. Sadly, I fear the worst; it doesn’t appear to have even made it to paperback.

The book is, as you would expect, full of rage. In subsequent media interviews (he went on to campaign for a change in the law on bail) he is careful to frame the debate in terms of two equal victims — the person assaulted and the person falsely accused. Apart from the outrageous way that Gambaccini and others were treated, one of the troubling things for me, as a long-time Guardian reader, is that Gambaccini — himself a lifelong Labour supporter and active fundraiser — is clear that his most vocal support came from the right-wing commentariat, the likes of Richard Littlejohn. From The Guardian, nothing. It has a different agenda.

And of course the book throws a spotlight on the shocking state of our justice system, which faces death by a thousand cuts. This case seriously stretched someone like Gambaccini, a relatively wealthy individual with access to extremely rich friends. The awful reality is that ‘justice’ in such cases is the preserve of the rich and almost certainly out of the reach of people of ordinary means.

Gambaccini himself — the ‘professor of pop’ — is a thoroughly likeable chap, which we knew anyway, I suppose. There is more than a little humour mixed in with the rage, and he can be forgiven the odd wince-inducing remark. Top of the latter list: “As a Royal Shakespeare Company veteran turned franchise icon might say, make it so.” It’s a reference to Patrick Stewart, if you aren’t a Star Trek fan.

5 September

Freddie Mercury’s birthday. Yesterday I asked some friends how old they thought he would be if he were still alive. Nobody went above 70. He would actually be 74 today. Although Queen’s first album only came out in 1973, they are of a similar age to others who broke through in the sixties. Jimmy Page and Roger Daltrey, for example, are both 76.

7 September

Time for some serious film watching ahead of the new football season. One that has been waiting in the My Recordings folder for far too long is The Post. Steven Spielberg, Tom Hanks, Meryl Streep; why on earth did I not watch this the day it was first shown?

Written around the publication of the so-called Pentagon Papers in the early seventies (which basically showed that the US government had been lying about the war in Vietnam for a very long time), it is a prequel of sorts to All the President’s Men, the story of the Watergate exposé starring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman.

This time around there is no Woodward and Bernstein. The star of the show is the Washington Post’s editor, Ben Bradlee, played by Tom Hanks. The film has an unashamedly liberal agenda and, though set fifty years ago, its central message — the freedom of the press is a sine qua non of a liberal and democratic society, holding those in power to account — resonates in the Trump world of ‘fake news’ and naked attacks on the media.

I wrote the following about Darkest Hour, the 2017 film about Winston Churchill in 1940:

Films about personalities and events from the past nevertheless reflect the mood, norms and expectations of the times in which they were made. With diversity and inclusion society’s current watchwords, any film about events dominated almost exclusively by socially privileged white men will throw up interesting challenges for director and scriptwriter.

Diogenes, Darkest Hour film review

I doubt there are many settings more “dominated almost exclusively by socially privileged white men” than the upper echelons of the Washington Post in the seventies. Thus, running in parallel with the journalistic scoop story, the script follows the tribulations of the paper’s owner Katharine Graham, who is played by Streep.

I don’t know anything about what really went on behind the scenes at the Post. Graham is portrayed in the film as a woman at first seemingly out of her depth, having been placed in the hot seat by the death of her husband. The decision to publish the secret documents could bankrupt the paper. Should she authorise publication or not? Eventually standing up to the (all male) board — with the great Bradley Whitford playing a deliciously sinister role, his naked chauvinism visible for all to see by the film’s end — she backs her editor.

12 September

Well, I have finally broken my unwritten rule of alternating between fact and fiction this year. A number of books have been shouting at me to be re-read, I think because I noticed that the Labour politician Lord Adonis has written a biography of Ernie Bevin. I am very tempted to re-read the third volume of Alan Bullock’s biography, but it’s about 900 pages (and the text is unusually small) so I will wait until I am a bit less busy.

The Adonis book reminded me of the biography of Aneurin Bevan I read a year or so ago by Nick Thomas-Symonds, who is currently the shadow home secretary. He might be a former Oxford academic and a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, but it was a really disappointing book. I am not a huge fan of ‘serving’ politicians writing books about their heroes. Having said that, I do want to re-read Michael Foot’s Bevan biography, if only to enjoy it as a literary treat (and, yes, I know, I didn’t enjoy Foot’s biography of HG Wells).

In the end I decided to re-read Age of Capital, the second volume of Eric Hobsbawm’s history of the ‘long’ nineteenth century. I re-read Age of Revolution last year, and I plan to get round to Age of Empire again at some point to complete the trilogy.

14 September

I watched the fourth and final episode of Lethal White, the latest TV outing for Strike, the London private detective created by Robert Galbraith, better known as JK Rowling. I have never actually checked but I assume that the pseudonym is at least in part linked to JK Galbraith, the famous liberal economist. Strike is something of a rarity for me: a drama that I found at the very beginning (I actually went back and watched The Cuckoo’s Calling on iPlayer last week), and I am so glad I did.

The plot of Lethal White is ridiculously convoluted and hard to follow (made even worse because I watched the episodes more or less as broadcast, with a week’s gap in between, and I have a memory like a sieve; normally I record them and watch the whole thing in my own time), but it didn’t really matter because much of the drama actually revolves around the relationship between Strike and his assistant Robin. Two convincingly drawn characters, a great ongoing will-they-won’t-they thing, and brilliant performances from Tom Burke and Holliday Grainger (who reminds me a bit of Jodie Comer, also sensational as Villanelle in Killing Eve).

15 September

After a run of first-class films I have hit a brick wall of sorts with Ad Astra. It’s one of those films which I think we are meant to regard as deep and meaningful, but it didn’t do a huge amount for me; maybe I wasn’t paying enough attention. I have never been a huge fan of first-person voiceovers: is it me or do they always sound phlegmatic and, dare I say it, bored?

I assume the echoes of Apocalypse Now, itself based on the novella Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad, are deliberate: a journey into the unknown; delusions of grandeur; the questioning of old certainties.

In its visuals I suppose it will be compared to 2001: A Space Odyssey. There were indeed some impressive scenes (none more so than the opening sequence where he plunges to earth from an impossibly tall structure that reaches into space). The extra-vehicular goings-on in Neptune’s orbit were stunning but completely ridiculous. The buggy chase across the Moon actually reminded me of Diamonds Are Forever as much as anything, and the Mars interiors looked like something from a Gerry Anderson set.

16 September

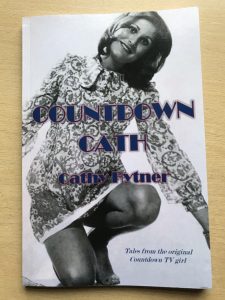

I am always amazed — perhaps ‘incredulous’ is the word — when some cultural or intellectual figure of note, quizzed on what they are currently reading, promptly reels off four or five titles. It is rare that I even have two books on the go at the same time. My brain just can’t handle it, and I also have a vague sense that it is disrespectful to the author. I have made an exception at the moment, if only because the second one isn’t actually a standard book as such. As well as Hobsbawm I am reading Countdown Cath.

The ‘Cath’ of the title is Cathy Hytner, best known as one of the original Countdown presenting team back in the early eighties. As I say, it is very different from the books I normally read. For starters, it is extremely slight — 80 pages, about 10 of which are of photographs. Nor is it a product of the ‘official’ book world. Rather, it is a more or less DIY effort, published with the help of a friend, I think. Don’t pick it up expecting a polished publication.

Covering the period from her childhood in the fifties to leaving Countdown in the late-eighties, this collection of memories was written in self-isolation during the lockdown of March onwards. In an afterword, Cathy describes the writing experience as “cathartic”. For the reader, meanwhile, the very first paragraph of a blurb on the opening page — “unwanted fourth daughter”, “neglected childhood years”, “hidden cost” — prepares us for what is to come.

It is an unvarnished and at times sad and deeply moving tale. Its mini-chapters (sometimes less than a page in length) — and particularly the repeated use of titles beginning with the words ‘Picture This’ — add to the sense that Cathy is candidly showing us snapshots from the life of a working-class girl from Manchester. It isn’t all grim up north. There is laughter mixed in with the tears and glamour as well as gloom. But, at a time when one side in the culture war rages that demands for equality are a sign that the world has gone mad, Cathy’s stories from the modelling and TV worlds of the seventies and eighties are a timely reminder of the abysmal way in which we are capable of treating each other — and, indeed, routinely did not all that long ago. A quick glance at Gyles Brandreth’s published diaries, Something Sensational to Read in the Train, confirms that producer John Meade was indeed a complete shit.

With a bit of imagination I can join the dots between the houses, shops and streets of Cathy’s childhood and my early-years visits to my grandmother’s house a decade and a half later. It was a warm, welcoming and loving household; I was lucky. But, even as a young child, I had a sense of the make-do-and-mend reality of Nanna’s day-to-day life. It wasn’t just the television that was in black and white. To slightly misquote Harold Macmillan, most of us have never had it so good. It is all too easy to look back nostalgically on the good old days that, in reality, never actually existed.

17 September

I finished the Hobsbawm book. As usual, he writes in the preface that the book is aimed at the general reader (his own Age of Revolution puts it best: “that theoretical construct, the intelligent and educated citizen”). I am intrigued to meet this general reader. As someone who has been reading history for forty years I find Hobsbawm’s histories never less than challenging: wide-ranging, learned and — despite his protestations — requiring more than a passing familiarity with at least the main events of the period. Curiously, my (paperback) edition shows the copyright as 1962, but it was in fact published in 1975.

For all Hobsbawm’s intellectual prowess the book does have serious flaws. The repeated references to Marx date it somewhat (and its unapologetically Marxist perspective paints the world in bleak terms). Despite its global canvas it defaults repeatedly to Europe, principally Britain and France. I will frankly have to re-read the chapter on the arts to get to grips with what Hobsbawm was arguing. More generally, for a lifelong champion of the so-called lower classes, his observations on culture are extraordinarily elitist.

The great Richard J Evans has written a brilliant biography of Hobsbawm, and it is to Evans’s The Pursuit of Power rather than to Hobsbawn that I would now turn if I wanted an overview of the nineteenth century.

22 September

Reading Eric Hobsbawn has led me back to EP Thompson, another great Marxist historian. I am re-reading The Crisis of Theory by Scott Hamilton.

Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class, published in 1963, is hailed as a classic, breaking new ground in terms of its subject matter and its methodological approach. He fell out spectacularly with Perry Anderson and the New Left Review circle of Marxists in the sixties and seventies. While they were under the spell of continental Marxists and a ‘cold’, structuralist approach to thinking about history and society — a sense that we are powerless in the face of ‘objective’ economic laws — Thompson emphasised consciousness and agency. He combined this with a fierce pride in the struggles of ordinary people throughout (British) history.

Some of Thompson’s ideas now seem hopelessly romantic — indeed, towards the end of his life he seems to have become disillusioned not just with Marxism but with the left more generally — but the values that underpin his ‘socialist humanism’ strike me as more relevant than ever.

24 September

After a run of non-fiction reading it was time to pick up a novel again, as per my new year’s resolution. I have read pretty much everything by Sebastian Faulks, including On Green Dolphin Street earlier this year. I count Human Traces as one of my all-time favourite books. For some reason I haven’t yet read his latest — Paris Echo — even though it was published in paperback in 2018. So, here goes …

29 September

Paris Echo has all the familiar Faulks trademarks, not least an incredible sense of place. If I had to sum up in one word what I love about Faulks’s writing, it would probably be ‘interweaving’. It is there in all his books but is absolutely central to this one — the ‘echoes’ of the title. One story weaves in and out of another; characters intermingle, one with another; the past intersects with the present; locations intersect with stories. It is all wonderfully, wonderfully crafted. Overarching it all is a deep love of, and respect for, the past.

We are back in Faulks’ beloved France. The two central characters are Hannah, an American historian researching women’s experiences in Paris during the Occupation, and Tariq, an undocumented Moroccan immigrant, whose family history has been shaped by France’s colonial past. Both arrive in Paris looking for something, though neither is clear quite what that ‘something’ is.

The novel is full of mystery. There is the fragility and contingency of Hannah’s work, as she tries to reconstruct the past. As a historian by training and someone who reads a lot of history, I was struck by the observation that people who live through ‘historic’ events might not experience them as such, especially if their most pressing day-to-day priority is simply survival.

There are many unanswered questions surrounding Tariq, too. What was the traumatic experience in his family’s recent past? What is the nature of his out-of-body ‘autoscopic’ experiences? Is Clemence real or just a drug-induced hallucination? For the reader it is frustrating — but fitting — that Faulks doesn’t give us any easy answers to these and other conundrums.