Books, TV and Films, June 2020

6 June

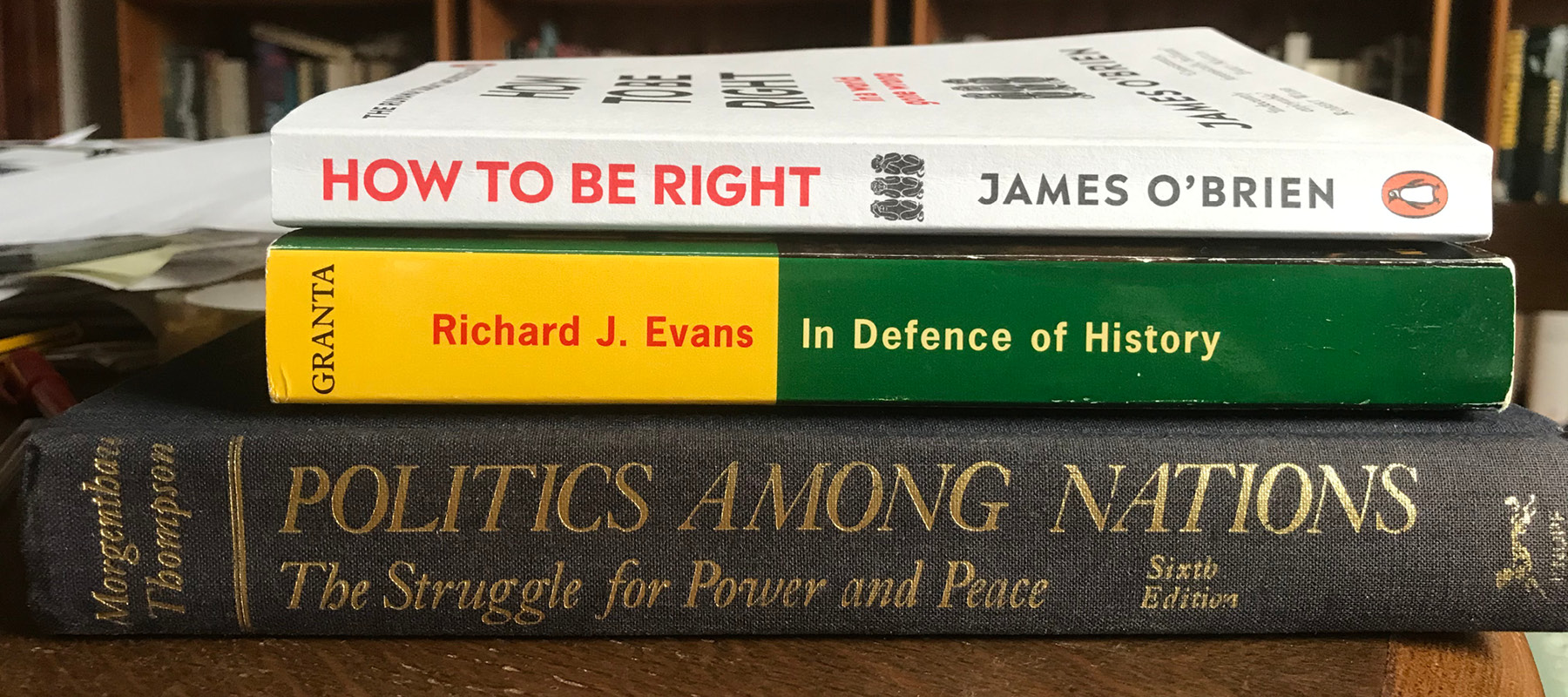

After seeing a tweet from the great Steven Pinker a few days ago, I decided to reread Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace by Hans J Morgenthau.

It was a book that I used a lot at university. My own copy of it means a great deal to me. As I was constantly borrowing it from the library, I asked my parents to buy me a copy one Christmas way back when. This was long before Amazon and online shopping, of course. My parents would have been reluctant to go to a major city to visit an academic/university bookshop that might stock a copy, and so they ended up ordering a copy from a local bookshop. It arrived weeks later, beautifully bound but costing something like £25 — an awful lot of money for a book back then.

It is a classic of political science, not a work of history. Though half of my degree was in international relations, I consider myself a historian, certainly by inclination: I had originally chosen to do a joint degree with international relations because I was worried (with good reason at the time) that the history syllabuses would stop in or around 1945.

I quickly realised that I was far more comfortable with the contemporary history elements of the international relations course than with the analysis of contemporary systems and structures. Most of the books on the reading lists were American (like this one), and the pseudo-scientific, theoretical approach used to get on my nerves (I suppose that’s why it’s called political science … doh!). Sometimes it seems like they are just stating the obvious. Take this quote:

When we say that the United States is at present one of the two most powerful nations on earth, what we are actually saying is that if we compare the power of the United States with the power of all other nations … we find that the United States is more powerful than all others save one.

Hans J Morgenthau, Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace

Well, blow me down.

13 June

I finished the Morgenthau book today. It was originally published in the late-1940s (as the Cold War was kicking off). It was groundbreaking and highly influential in its day, not just on university campuses but in political and diplomatic circles. It went through several editions over the years. My copy (the sixth — and final? — edition) was published after the author’s death, with updating done by a professional colleague.

Leaving aside discussion of the ‘realist’ perspective that Morgenthau adopts, two thoughts about the book come to mind.

It is a long book, No doubt the process of preparing a new edition requires a great deal of time and effort, but the ‘joins’ between the original and newer sections of the text are glaringly obvious. Some of this sixth edition, published in the mid-1980s, seems to be the original, unaltered text written in the ’40s. Then there is the briefest of discussions of Nato and the ‘European Communities’, which clearly dates from the ’50s. In the section on the United Nations, meanwhile, statistical information stops abruptly at 1965 — presumably when that portion of the book was last updated. Other parts of the book, on the other hand, talk in some detail about Reagan and developments in the 1980s. I’m not sure that I noticed it at the time but now it strikes me as rather unsatisfactory.

The main takeaway, however, is how much the international scene has changed. Even my sixth edition was published in a ‘bipolar’ world that assumed a global struggle for supremacy between the United States and the Soviet Union. China was an impoverished minor actor on the world stage, taking its first faltering steps on the road to industrialisation. The environment is mentioned occasionally — though nothing as specific as climate change — and, according to the index, there is just a single reference in the whole book to terrorism.

15 June

As a longtime history teacher, I am listening in some despair to the ‘statues’ debate that has erupted following the death of George Floyd in the USA and to the discussion that surrounds it about the teaching of history. I was troubled by two comments from activists quoted in the Guardian in the last few days:

That history [of the nineteenth-century imperialist Cecil Rhodes] will never be erased, it’s a lived reality for people in southern Africa, but it needs to be contextualised, it needs to be accurately represented and not glorified in the way it is today.

Decolonising the curriculum means providing an accurate portrayal of history …

I instinctively find phrases like “accurately represented” and “accurate portrayal” alarming. What worries me is that, other than those on the right with their own small-‘c’ conservative agenda, nobody seems to be picking this up. Before commenting further, I want to go back over a few things in my head, so I am rereading In Defence of History by Richard J Evans.

18 June

I am not quite sure why I thought the Evans book would be particularly helpful. It was written in 1997, primarily in response to the rise of postmodernism and the threat to what most people would think of as history. My main takeaway from the book is what utter drivel many of the so-called ‘intellectual historians’ and philosophers of history — people who focus on the theory and writing of history, not on the events of history itself — write. They do themselves no favours. Time and again they express their ideas in overblown, pretentious language, — or, as they might say, ‘at an appropriate level of abstraction’. It is as if they believe that writing in a way that is deliberately abstruse and impenetrable somehow proves how profound and worthy it is.

I suppose the book reinforces my conviction that there is no single, universally agreed, true story of the past ‘out there’ waiting to be told in the correct way. Talk of “an accurate portrayal of history” is therefore less than helpful. Accurate — according to whom? Who gets to decide?

23 June

I headed to my local Waterstones again today. If anybody is reading this years in the future, a visit to a bookshop is indeed noteworthy because all the shops have been shut for months due to the coronavirus pandemic and are only slowly, tentatively, reopening their doors.

I don’t have the second volume of Richard Evans’ history of Nazi Germany (I am working my way through the three volumes), so I thought I would go into the shop to buy it and show my support. Surprisingly, neither their large-ish Preston branch nor the smaller Wigan branch stocked any of the three volumes. Anyway, I ordered it and it arrived within two working days. Well done them.

Mooching around the ‘buy one get one half-price’ tables, I picked up the latest Ian McEwan novel, Machines Like Us, and a book I have been itching to buy for some time: How to Be Right by James O’Brien. It feels like the perfect time to get a bit of clear thinking from O’Brien. The online clips from his radio phone-in show really are essential listening.

In a media world dominated by right-wing newspapers, loudmouth columnists and shock-jocks, O’Brien’s is a rare voice of the moderate centre-left. He is hated by those on the opposing side in our ever more visceral culture wars. Of course I am biased but he really does strike me as a voice of reason, with a refreshing willingness (in the book at least) on things like wearing a burqa in public to say: ‘I’m not sure’.

30 June

Well, the James O’Brien book was a quick read — just two days — though it is one I will doubtless dip into again and again. The paperback edition includes a short afterword and is another reminder of why I very rarely buy ‘current affairs’ books. It was written in April 2019 and is about Brexit. But the political landscape is changing so quickly that, already, it feels completely out of date. Much journalistic commentary — however insightful the writer — is inevitably contingent and quotidian, quickly superseded by events. Tomorrow’s chip paper. That’s why, though very tempted, I have resisted buying any of the books published about the Trump presidency.

That’s also why I no longer buy biographies of serving prime ministers or other new faces suddenly propelled into the limelight. I think the first one I ever bought was Hugo Young’s biography of Thatcher, One of Us, written I think in 1989. She was defenestrated a year later. Such books — another one I bought in the mid-’80s is Mrs Thatcher’s Revolution, written by another Guardian columnist of the time, Peter Jenkins (late husband of Polly Toynbee) — are best read now as historical texts, offering an insight into the mindset of the times in which they were written, rather than as reliable, in-depth accounts of what happened.

And finally this month, a quick mention of two films that I have just caught up with: Philomena and On Chesil Beach. Both absolutely delightful. Both unbearably sad. Both wonderfully acted. More thoughts on these and other things next month.