Awe and Wonder

It is probably Hollywood’s most enduring movie myth, that when the director of The Greatest Story Ever Told suggested to John Wayne (in a cameo role as the Roman centurion guarding the dying Jesus on the cross) that he deliver the line ‘Truly he was the Son of God’ with a bit more awe, Wayne came back with “Aww, truly he was the Son of God”. The ‘awe and wonder’ moments — it’s a decent working definition of what we mean by spirituality in the curriculum. And there are few things more awesome than gazing up into the heavens on a clear and cloud-free night — which is why the ambition of Scotland’s astronomer royal to give every child a window into the universe is so exciting.

The astrophysicist Professor Catherine Heymans is Scotland’s new astronomer royal. She herself did not even look through a telescope until she worked as a tour guide at Edinburgh’s Royal Observatory to help pay for her education. Now, she says in a Guardian interview, she is hoping to give every child the chance to do so by installing telescopes at Scotland’s residential outdoor learning centres, where children traditionally spend a week in their final year of primary school.

She says she got the idea after her own children returned from a school trip: “The centres are all in these fantastically remote locations, so the skies are really dark. It’s a perfect place to do astronomy, and all our kids, no matter what background they come from, will pass through one of these centres, so what a way to reach everyone.”

England’s national curriculum for science covers ‘Earth and space’ in year 5 (when children are aged 9 and 10). However, the dry language of the document fails to capture the beauty and wonder of the cosmos and its ability to profoundly move us. Richard Dawkins is (as always) word-perfect in his book for young people, The Magic of Reality, when he talks of ‘poetic magic’:

We are moved to tears by a beautiful piece of music and we describe the performance as ‘magical’. We gaze up at the stars on a dark night with no moon and no city lights and, breathless with joy, we say the world is ‘pure magic’. We might use the same word to describe a gorgeous sunset, or an alpine landscape, or a rainbow against a dark sky. In this sense, ‘magical’ simply means deeply moving, exhilarating: something that gives us goose bumps, something that makes us feel more fully alive.

from The Magic of Reality, Richard Dawkins, Chapter 1: What Is Reality? What Is Magic?

Awe and wonder is an essential element of truly inspirational teaching and a truly enriching curriculum. Not every child can escape the city lights. Still fewer will be lucky enough to own their own telescope and to have access to a garden in which to begin their voyage across the vastness of space (though this is a great article from the BBC’s Sky at Night magazine on getting children started with astronomy). That’s why we need ambitious and radical thinking — and the investment to support it — if we are to provide those life-changing ‘light switch’ experiences for children of all backgrounds.

It is brilliant initiatives such as Professor Heymans’ idea of giving every child the chance to peer into the infinite that are key to firing children’s imagination. Who knows where it will lead: we may witness the birth in the coming years of a new galaxy of bright and gleaming stars — scientists, engineers, inventors and the like, leading their respective fields in tackling the immense challenges the world faces, their passion for exploration and discovery triggered by a peek into the Great Unknown on a remote Scottish hillside years earlier.

I blog regularly about education, particularly in relation to children aged 5 to 11, at this website about Life-Based Learning.

Image at the head of this article by Lizeth Lopez from Pixabay.

Books, TV and Films, May 2021

1 May

In 2019 a Guardian writer described a particularly tricky challenge for filmmakers attempting to portray the subject of poverty convincingly: “Go too far one way and you are accused of romanticising hardship; head in the opposite direction and you’re poking sticks at poor people for entertainment.” In other words, at one end of the spectrum is an overly romanticised nobility-in-poverty view of the hardships of living with little or no money; at the other end is exploitative ‘poverty porn’ à la Channel 5.

The tough-to-watch Ray & Liz gets it spot on, helped by the fact that elements of the story apparently incorporate director Richard Billingham’s own childhood experiences. It is a harrowing depiction of the devastating impact of poverty on people’s lives, with children of course suffering the greatest harm. There is no nobility in poverty here. Just squalor, desperation and neglect. This viewer struggled to feel any sympathy for the parents; it certainly wasn’t the film “full of love” that the Observer newspaper’s reviewer Wendy Ide apparently watched.

5 May

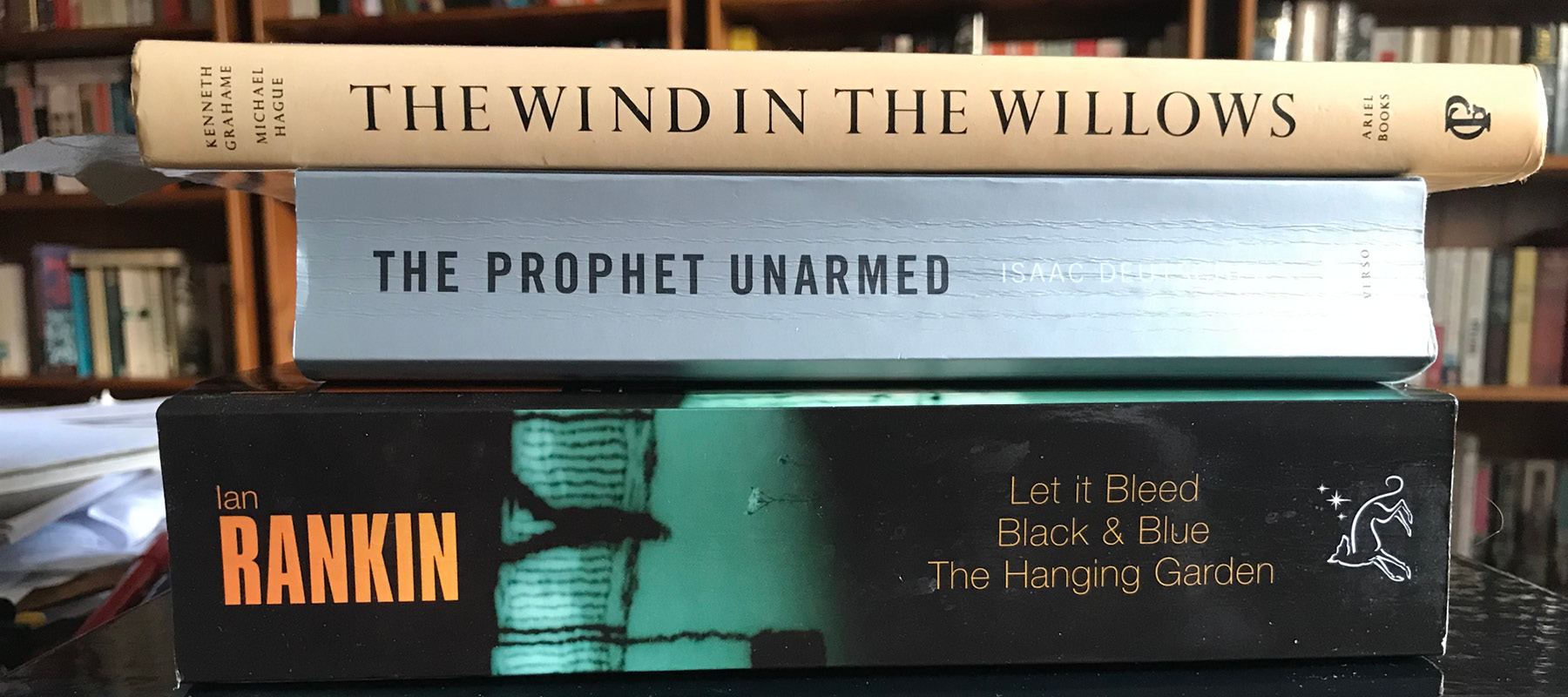

Back to Scotland. Back to Rebus. Another title taken from a Rolling Stones album and suggestive on several levels — this time it’s Black & Blue. The book itself is on a grander scale than the previous Rebus novels. For starters it is considerably longer. It also has a much broader geographical sweep, encompassing Glasgow, Aberdeen and the off-shore rigs, and the Shetlands as well as Rebus’ usual Edinburgh stomping ground.

My copy of Black & Blue is the second of a three-book omnibus called The Lost Years. But cutting through the familiar fug of cigarette smoke and whisky fumes is something brighter and more optimistic. Rebus himself is reacquainted with an old friend DI Jack Morton and for a significant portion of the book keeps off the cigarettes and alcohol. It will be fascinating to see where Rankin takes Rebus in the next instalment, The Hanging Garden.

11 May

The Prophet Unarmed, the second volume of Isaac Deutscher’s classic biography of Leon Trotsky, covers the period from 1921 to Trotsky’s banishment from the Soviet Union in 1929. Much of what occurs in the book flows from three key moments: the ban on factionalism imposed at the Tenth Party Congress in 1921, the introduction of the New Economic Policy (a hugely controversial U-turn by the Bolsheviks, which permitted the return of a small-scale private sector in agriculture) and the incapacitation through ill-health and then death of Lenin.

The ban on factionalism was introduced in an attempt to ensure unity at a time when the survival of the revolution itself was gravely imperilled. The effect, of course, was to stifle all legitimate debate, deliberation and argument. Whoever was in charge of the machinery of decision-making effectively controlled the levers of power as well. As general secretary of the party, that person was Stalin. Those who challenged or questioned the ‘correct’ line were described as ‘deviationists’, ‘oppositionists’ and ‘counter-revolutionaries’.

For a movement obsessed with history — particularly the French Revolution — the past itself increasingly became a battleground. Truth was now a weapon of war, to be used and abused in the struggle for power. It began with a rewriting of the events of 1917 to hide the real attitude adopted by Zinoviev and Kamenev, who were by now allies of Stalin against Trotsky:

This was done timidly at first, but then with growing boldness and disregard for truth … This version was so crudely concocted that even the Stalinists received it at first with embarrassed irony. But once put out, the story began to crop up stubbornly in the new historical accounts until it found its way to the textbooks, where it was to remain as the only authorised version for about thirty years. Thus that prodigious falsification of history was started which was presently to descend like a destructive avalanche upon Russia’s intellectual horizons…

The Prophet Unarmed, Isaac Deutscher, p128

It makes for sober reading when — one hundred years later — the very concept of objective truth is again seemingly up for grabs, when facts are routinely ignored or falsified, and when history is subject to manipulation, oversight and control, and not just in parts of the world under authoritarian rule.

15 May

These 9pm dramas are becoming an enjoyable habit. ITV’s new ‘psychological thriller’ Too Close was perfectly pitched — three episodes, roughly 45 minutes each, showing on consecutive nights. Long enough to add depth but not so long that it starts to overstay its welcome by losing coherence or simply running out of legs (Killing Eve springs to mind at this point).

It maybe stretched credibility once or twice — Connie seemed to have uncanny mind-reading abilities in the way she deconstructed Dr Robertson’s private life in a matter of minutes — but the one-on-ones were good (I had read that people who like the long interviews in Line of Duty would like this too), the portrayal of a psychotic breakdown was excellent and the two central performances by the ever-reliable Emily Watson and Denise Gough were outstanding.

22 May

I have never — either as a child or as an adult — been much of a reader of classic children’s literature. Not for me the likes of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Black Beauty and Treasure Island. I read The Railway Children for the first time in my thirties and Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in my forties — and in both cases not just for enjoyment. In the case of Alice, I was curious about the character the White Queen and whether there are any lyrical connections with White Queen (As It Began), which is one of my all-time top three favourite Queen songs.

As for The Railway Children I wanted to know more about any political undercurrents in the text and, in particular, what additional light the book sheds on the circumstances surrounding the imprisonment of the children’s father; the (wonderful) film always seemed to me, remembering it from childhood, somewhat vague on this point. It was published as a novel in 1906 and the author, Edith Nesbit, was an active socialist. The Dreyfus Affair — the imprisonment in France of a Jew falsely accused of spying — had been a cause célèbre on the European left since the late-1890s. There are also anti-Tsarist references in the book; Nesbit was presumably writing it at about the time of the Russo-Japanese War and the revolution of 1905.

Having recently been given a nicely illustrated edition of The Wind in the Willows (another Edwardian novel, written by Kenneth Grahame and published in 1908), I have enjoyed meeting and learning more about characters like Mole, Rat, Toad and Badger whose names have always been familiar despite me never having read the book before. It’s a beautiful read, so full of imagination and innocence (though here and there faintly unsettling too), an escapist delight in these difficult and turbulent times.

I was sold even before the end of page one: “So he scraped and scratched and scrabbled and scrooged, and then he scrooged again and scrabbled and scratched and scraped…” The contents page confirmed a vague music trivia recollection about the first Pink Floyd album, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn. This and Wayfarers All are my two favourite chapters (so far at least), lyrical, enchanting and mystical.

25 May

Action-hero movies are one of my guilty pleasures — usually after several pints, when I don’t feel quite so guilty. Is John Rambo perhaps the tough guy’s tough guy? The Rambo franchise has been around for an unbelievable forty years. Sylvester Stallone is now in his seventies but still manages to kick some serious bad-guy ass.

Rambo: Last Blood is depressingly familiar fare (in other words, genre fans will love it), this time with an extra dollop of sadistic violence on top. The plot — Mexican cartels forcing Rambo’s adopted niece into sexual slavery — seems to be pitched fairly and squarely at Trump devotees, though they surely can’t be happy that after nearly a full Trump term it was so goddam easy for the slimeballs to cross the border. Build that wall!

It’s all a long way from 1982’s First Blood — the first and by far the best Rambo film — which, for all the opprobrium that came its way after the release of the follow-up in 1985, was actually a thoughtful depiction of a country still struggling to come to terms with the Vietnam War as well as being a thrilling survival/chase movie. Nobody in First Blood is actually killed, and yet I remember a newspaper op-ed (I think in the Daily Mail … enough said) after the Hungerford massacre of 1987 declaring that First Blood would never again be shown on British television.

28 May

The quality TV crime dramas just keep on coming. Marcella, Line of Duty, Unforgotten, Grace, Too Close. My latest binge-fest is Innocent. Series two is showing at the moment and (yippee) series one is still available for free on the ITV Hub.

Two-and-a-bit episodes in and Innocent is another well-constructed and enjoyable storyline that treads (admittedly very) familiar ground — a family man sentenced for murdering his wife, a possible miscarriage of justice and a tangled web of secrets, deceit and cover-ups. Innocent is particularly strong on the devastation that traumatic events visit on the survivors; as the police investigation reopens, it doesn’t take long for the brittleness of patched-up and patched-together relationships to become apparent. It equally quickly becomes clear that the title refers as much to the family’s teenage children as it does to the convicted husband.

The least credible aspect — and for me an unnecessary plot complication — is that the senior officer appointed to lead the new police investigation is in what appears to be a not altogether convincing secret relationship with the senior officer who led the original investigation and whose I-know-the-bastard-did-it-really dereliction of duty she quickly uncovers.

Books, TV and Films, April 2021

3 April

I avoid opening Amazon’s emails telling me what their omniscient algorithms think I should be buying and I never even look at the latest fiction and non-fiction charts so, other than skimming the Guardian’s Review magazine on Saturdays, I am always rather in the dark about new book releases. Now that bookshops are open again — well, they will be in a few days — it’s an opportunity to start paying more attention to new writing in history, biography and politics. (Though I remain loath to buy books about the contemporary political scene, which almost by definition date very quickly, I will probably make an exception for Peter Oborne’s The Assault on Truth, a favourite topic of mine these days.)

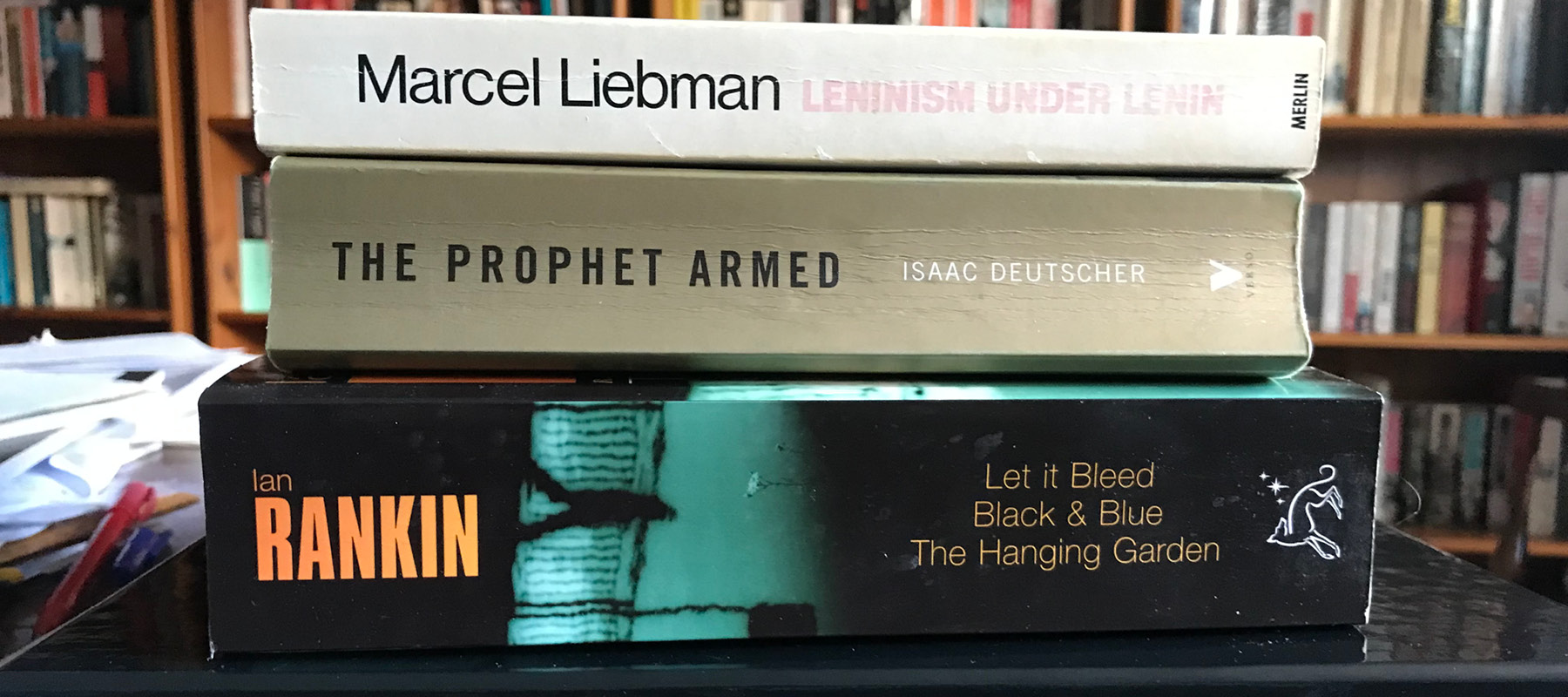

More than ever this last year I have been drawn back to old favourites — books that first made an impression on me years ago, or that have outstanding literary merit, or that are recognised as classics. High up on that list is the three-volume biography of Leon Trotsky by Isaac Deutscher. Volume I is called The Prophet Armed and covers the years up to 1921.

Deutscher is widely recognised as one of the outstanding Marxists of the time (he was active from the late-1920s until his death in 1967) — a highly influential activist, historian and journalist. The Prophet Armed is beautifully written. Though its scholarship will now of course be superseded, at the time (it was published in 1954) it made extensive use of previously unavailable material. And, although Deutscher is very much associated with the Trotskyist wing of world communism, his biography is by no means hagiographic, paying due attention to Trotsky’s flaws, mistakes and misjudgements.

Trotsky has always struck me as — even more than Lenin — the towering figure of the Russian Revolution. He was a more charismatic leader than Lenin, a more engaging public speaker, a more gifted writer and to my mind (though this is certainly arguable) a more daring strategist and effective organiser and administrator, certainly in the period from 1917 to 1921. It was Trotsky who was at the centre of events in 1905, as chair of the Petrograd Soviet. It was Trotsky who masterminded the seizure of power in October 1917. And it was Trotsky who created the Red Army from virtually nothing and ‘saved’ the revolution from defeat in the ensuing civil war.

Much writing about the Russian Revolution itself — perhaps most notably in recent years the work of Robert Service, formerly professor of Russian history at the University of Oxford — comes from historians whose work is influenced by their hostility to communism, perhaps involving the conviction that the later horrors of Stalinism and the broader failings of the Soviet state were/are an intrinsic part of the communist package, or who assume that the revolutionaries were all along motivated largely by cynical, violent and base urges. The sympathetic pen of Deutscher, on the other hand, reminds the reader of what the revolutionaries themselves believed they were fighting for — the introduction of true equality between all peoples and the flourishing of genuine freedom and democracy through the eradication of all forms of exploitation.

All of which gives the closing chapter of Volume I in particular —entitled Defeat in Victory — the air of Greek tragedy: the opponents of imperialist war waging aggressive war against Poland; the emancipators of working people introducing forced militarisation of labour and the widespread use of terror; the proponents of true democracy instituting a one-party state, banning dissent even within the Communist Party itself and crushing rebellion at the previously loyal Kronstadt naval base.

5 April

Not being a telly addict I have missed out on a huge amount of quality television over the years. Take your pick from the last thirty-five years – Our Friends Up North, 24, The Sopranos, Breaking Bad: a mouth-watering smorgasbord of highly acclaimed drama and I haven’t seen any of them.

Part of the problem is that by the time a programme becomes a bleep on my radar, it’s already too late: the series is underway, plots and characters are established, threads are busily interweaving and knotting. Okay, I am exaggerating. DVD box sets have been around for ever (though it’s an expensive mistake if a programme turns out to be a turn-off rather than a turn-on) and cable/satellite TV, catch-up TV and TV on demand mean that, unlike in the old days, I can make the effort if I really want to. Plenty of ‘classics’ repeated from the very beginning. Take The Eagle’s Nest, for example, the first ever episode of The New Avengers from 1976, which I watched (again) recently. Who can resist a Hitler-didn’t-really-die-in Berlin-in-1945 plotline?

To quote The West Wing’s Sam Seaborn, let’s ignore the fact that I arrived at the party late and celebrate the fact that I have turned up at all. I first watched both Friends and The Office about a decade after they initially aired. The ten series of Spooks filled much of the first lockdown, and I have watched all bar the first series of Unforgotten during the current one.

Which brings us to Line of Duty. Mother of God, it’s good. There’s the (admittedly rather daft) ‘Who is H?’ story arc, the Arnott–Fleming partnership (though the serious overuse of ‘mate’ is starting to grate) and then there are the Ted-isms. Now we’re sucking diesel.

Best of all are the set-piece extended grillings in the interview room: the cat and mouse, the shifts in the power balance, the perfectly cued-up evidence, the beautifully timed interjections — all apparently with no pre-interview preparation time from AC–12’s finest. Wonderfully executed dramatic licence. No doubt the reality is far less slick; try listening to any of the US president’s press secretaries (even the articulate ones) after watching a CJ Cregg monologue in The West Wing (again).

12 April

From Line of Duty and Unforgotten back to detective fiction; this time John Rebus rather than another Poirot. I first started collecting Rebus after noticing that they are a charity shop staple. My intention was/is to read them in chronological order. The first Rebus novel (written by Ian Rankin) was Knots and Crosses, published in 1987. I am up to the seventh in the series, 1996’s Let It Bleed.

I have a memory of Rankin saying that it was with this novel — or perhaps it was the next one, Black and Blue, which is considerably longer — that he felt that his writing really improved. There is a definite sense here of the two things for which the Rebus novels are perhaps best known: the city of Edinburgh itself, and the many backstreet dives that Rebus frequents — and loses himself in — both socially and professionally. The title, a reference to a Rolling Stones album (Rebus is a big fan), describes both the malfunctioning heating in Rebus’ flat and a painful gum abscess. It also serves as a metaphor for the corruption among Edinburgh’s elite that Rebus is investigating.

Let It Bleed is certainly an enjoyable read, excellently plotted and structured. One thing that slightly puzzles me about Rankin’s writing is that it is sometimes difficult to disentangle the narrator’s voice, which is infused with humour, irony and sarcasm, from that of Rebus himself. A couple of examples. The DCI has been seriously injured and the station talk is all about who will step into his shoes: “The rumours piled up faster than the collection money”. Then there’s a photo of a kidnapped girl “which somehow the media got their paws on”.

18 April

Don’t be fooled into thinking that McDonald & Dodds, one of ITV’s more recent detective dramas, is set in the city of Bath. The real location is the same alternate universe (© American Sci-Fi) as Midsomer Murders, where the sky is perpetually blue, the rolling countryside is liberally splashed with bright greens and yellows, and life rolls along at a sedate, self-satisfied pace. Swearing, litter and graffiti don’t exist. Even the mass murderers are considerate enough not to upset the idyll with anything as vulgar as a gore-splattered crime scene. The viewer is left wondering whether a body that has been hacked to pieces even bleeds.

The writers have managed to conjure up one more permutation of the ‘mismatched partners’ trope — this time it’s a dull, plodding but really quite sharp old hand (think Inspector Columbo) paired with an ambitious, brash but likeable woman of colour from the Big City. It’s all good cartoonish fun, an enjoyable antidote to the darkness typical of most crime drama. Chief Superintendent Houseman, however, is a caricature too far. Imagine a younger and (much) slimmer version of Chief Superintendent Strange from Inspector Morse. This comment (to DCI McDonald) made me laugh though: “You tick boxes that haven’t been invented yet.”

30 April

The odd thing about reading Leninism Under Lenin by Marcel Liebman (another thinker who, like Isaac Deutscher, was sympathetic to the Bolsheviks but not blind to their mistakes and failings) is that I was less clear in my understanding of how to define Leninism at the end of the book that I was before I began it. That’s not a fault of the book — for a work focusing as much on political theory as on actual historical events it is admirably clear and accessibly written.

I might previously have said that Lenin’s main contribution to the development of Marxism was the idea of a tightly knit group of professional revolutionaries held together by iron discipline. Yet Liebman shows that — both during the long years of Lenin’s exile before 1917 and even more so in the first years after the revolution — Lenin was regularly outvoted and his views opposed or ignored by various factions within the party (and I don’t mean the Mensheviks).

Or I might have said that the idea of the party as the elite vanguard of the working class, its historic role being to develop the revolutionary consciousness of the broad mass of workers who thought only in terms of economic wants, was the essence of Leninism. Yet the revolutions of both 1905 and February 1917 were essentially spontaneous uprisings, the Bolsheviks failing on both occasions to predict, still less to lead and direct, the flow of events — in the Bolsheviks’ own terms, the masses were ahead of the party in their consciousness.

At other times, however, the idea of the party acting in what it claimed was the objective interest of the workers — regardless of what the workers themselves wanted or believed at a particular moment — left the Bolsheviks open to accusations of ‘substitutism’, a charge levelled not least by Trotsky before he joined the party on the eve of the revolution. By 1921 (say) this charge carried real force and brought into question the legitimacy of the entire regime: with the collapse of industry and after years of civil war there hardly was a working class left in Russia and yet the Soviet government justified its single-party rule and its extreme measures in the name of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Books, TV and Films, March 2021

1 March

Having just watched the recent Elisabeth Moss film The Invisible Man, I am reading the original novel, written by HG Wells and published in 1897, the same year as Bram Stoker’s Dracula. I have never been scientifically minded but two film adaptations of HG Wells novels — The War of the Worlds (1953) and The Time Machine (1960) — made a huge impression on me as a child, which perhaps explains why I found remakes of both films (one with Tom Cruise and the other with Guy Pearce) disappointing.

Another childhood memory is a TV series called The Invisible Man, with David McCallum, who was already a hero of mine from his role in Colditz (which I was watching even at the age of about eight). Henry Darrow, perhaps best known for his role as Manolito in The High Chaparral, played a plastic surgeon who created a synthetic skin. At about the same time there was also a series called The Gemini Man, starring Ben Murphy (yet another childhood hero of mine from his role in Alias Smith and Jones), who could control his invisibility with a latest-thing-at-the-time digital watch.

But I always avoided the original Wells novels after my childhood self was intimidated by the very first line of The Time Machine:

The Time Traveller (for so it will be convenient to speak of him) was expounding a recondite matter to us.

The Time Machine, HG Wells

9 March

The opening chapters of The Invisible Man read almost like a piece of comedic writing. Gradually, however, the story moves to a much darker place as more and more of the invisible man is revealed to us. At first Griffin is brusque and bad tempered. Soon he becomes aggressive and violent. Eventually he is revealed as unhinged and completely amoral.

He steals to get much-needed cash. Then he matter-of-factly reveals that he robbed his father, who subsequently killed himself. Finally we learn of Griffin’s deranged vision: to be the autocratic ruler of a new society founded on a reign of terror, with punishments meted out by an unseen hand.

He [the invisible ruler] must take some town … and terrify and dominate it. He must issue his orders. He can do that in a thousand ways — scraps of paper thrust under doors would suffice. And all who disobey his orders he must kill, and kill all who would defend the disobedient.

The Invisible Man, HG Wells

I have always unthinkingly bracketed Wells as a champion of science, but in passages such as this he is surely exploring the darker places that the misuse of science can take us, thus foreshadowing some of the horrors of the twentieth century.

10 March

Channel 5 made a marvellous job of rebooting All Creatures Great and Small, but their latest attempt to muscle in on the world of Agatha Christie — Agatha and the Midnight Murders — is much less successful. Making Christie herself the focus is Channel 5’s way, so I read, of getting round the problem of having none of the rights to her books. This effort is set during the Second World War. Short of money, Christie is selling off the rights to her final Poirot novel (in which she kills off Poirot) to a private buyer, a superfan who will thereby keep Poirot alive. (I needed that last bit confirmed online because it wasn’t at all obvious from the script.)

It isn’t just Christie who is short of money. The whole production screams ‘low budget’. Much of the action takes place in a single location, the cellar area of a hotel; despite the confined space, the murderer seems to have no trouble bumping off his victims without being seen.

12 March

The Decline of British Power, written by Correlli Barnett, was published in 1972. It was the first of three books he wrote — the others were The Audit of War: The Illusion and Reality of Britain as a Great Nation and The Lost Victory: British Dreams and British Realities 1945–50 — that set out a ‘declinist’ thesis, basically that Britain experienced a catastrophic collapse in its political, economic and military power and standing in the twentieth century.

Though the focus of The Decline of British Power is the period between the world wars, the first part of the book makes clear that, in Barnett’s view, the roots of Britain’s decline stretch back into the nineteenth century. He targets a particular way of thinking, a dominant culture — what at one point he calls ‘romantic liberal idealism’. He is particularly scathing about the triumph of evangelical moralism which he says was responsible for a spiritual revolution that affected and infected the elite public schools in the high Victorian era, the formative years for many of those in positions of power after the First World War.

Instead of the suspicious minds of pre-Victorian statesmen, there was trustfulness; instead of a worldly scepticism, a childlike innocence and optimism. And instead of a toughness, even a ruthlessness, in the pursuit of English [sic] interests, there was a yielding readiness to appease the wrath of other nations … Whereas the pre-Victorian Englishman had been renowned for his quarrelsome temper and his willingness to back his argument with his fists — or his feet — now the modern British, like the elderly, shrank from conflict or unpleasantness of any kind.

The Decline of British Power, Correlli Barnett

His criticisms of a supposed anti-science and anti-technology bias in school curriculums, a major explanation (he says) for Britain’s subsequent chronic economic underperformance, are one reason that Barnett’s books were popular on the Thatcherite right in the ’80s and ’90s. The irony is that Barnett also identified free trade (central to the Thatcherite economic model, of course) as a cause of, rather than a solution for, Britain’s dismal economic record. Barnett was much more of an advocate of an active, interventionist state than the laissez-faire zealots.

The Decline of British Power includes plenty of footnotes. Nevertheless, at the back of the reader’s mind must be the concern that Barnett was presenting a very one-sided argument. The infamous Amritsar massacre of 1919, for example, when General Dyer ordered troops of the British Indian Army to fire into a crowd of unarmed Indian civilians, killing at least 379 people and injuring over 1,200 others, is described as being the result of “unfortunate decisions”. That’s one way of phrasing it. The deaths and the calculated humiliation of the local population led to “a spasm of moral indignation and philanthropic emotion in Britain”. To be clear, moral indignation and philanthropic emotion are bad things in Barnett’s worldview. He spits out phrases like “tender-minded”. There is no place for values like compassion or even duty (India, for example, should have been abandoned as a drain on the empire), still less for what we would now call an ethical foreign policy.

His ‘declinist’ thesis is a startling one: Britain achieved global pre-eminence when its strategy was dictated by ruthless self-interest. The reader is thus left with a second problem: was Barnett simply looking back fondly to the world of the eighteenth century or was he seriously advocating a return to such a nakedly amoral grand strategy?

16 March

Yet another new detective drama comes to the screen — Grace, based on novels by Peter James which to be honest I wasn’t aware of. It was a good idea to base this ‘pilot’ episode on the first book, as it nicely interweaves the storyline about a man who suddenly vanishes with a life-changing incident from Detective Superintendent Roy Grace’s own past. As with Unforgotten, I liked the portrayal of easy, informal relationships between the investigating team; the hostile, unsympathetic assistant chief constable, on the other hand, felt like something of a cliché.

20 March

The publication this week of the government’s integrated review of foreign and defence policy brought me back to thinking about the work of Correlli Barnett (see above). With all the caveats about Barnett’s approach to writing history, he nevertheless made a convincing case that Britain was woefully unprepared for the strategic challenges posed by Germany, Japan and Italy that arose in the 1930s.

Governments faced huge financial pressures, even before the Great Depression led to swingeing cuts in public spending; it was convenient economics as well as convenient politics to focus on disarmament and collective security through the League of Nations. Even when a programme of rearmament was belatedly introduced in the mid-1930s, it was not on the scale required. Nor were the opposition parties any more clear-sighted. The Labour Party, in particular, was all over the place in its thinking about defence, uttering pieties about collective security and yet repeatedly refusing to support the increases in defence spending required to make collective security credible.

Fundamental disagreements about foreign and defence policy between the political parties are not common. There is usually a basic consensus about Britain’s strategic requirements. That’s why, for all the political mudslinging, it almost invariably feels like politicians reading from pre-prepared, oft-repeated scripts. Regardless of which party is in government, increases in defence spending routinely attract criticism, especially if any other departmental budget is being reduced; cuts in defence spending or shifts in the balance of spending within the overall defence budget, meanwhile, are always cited as evidence of weakness on defence or of a lack of strategic thinking.

However, just as in the ’30s when there was no consensus about how Britain should defend itself and the ’80s when Labour adopted a policy of supporting unilateral nuclear disarmament, the current debate about the integrated review feels different, perhaps because so much of what is in it — particularly the so-called ‘pivot’ to the Indo-Pacific region — inevitably follows from the historically divisive decision to implement a hard Brexit and turn our focus decisively away from Europe.

21 March

The Sixth Lamentation is a book I picked up from a charity shop. Its title intrigued me, with the promise of some kind of religious, possibly supernatural theme (as in things like ‘The Ninth Gate’). I always enjoy starting a novel with no idea what it is about. Based on the opening twenty pages or so, it seems to be a historical mystery going back to Paris during the Occupation of the Second World War. If so, this is territory that Sebastian Faulks explored more recently with Paris Echo.

28 March

This year is the fiftieth anniversary of the release of Get Carter, regularly voted as one of the most important British films of all time (the equally good The Long Good Friday is forty years old). It is gripping viewing not just because it redefined the gangster film genre but also as a piece of social history, capturing a community in the grip of economic and cultural decline.

Much of the action takes place amid Newcastle’s working-class community. The backdrop of dilapidated housing and grim back-street locations, the use of documentary-style footage of the city’s pubs and clubs, and the depictions of brutal violence all combine to give the film a gritty and menacing authenticity. Sometimes it is the incidental details that stick in the mind: when Jack Carter is disturbed from his bed by two thugs and tumbles to the floor, there is a chamber pot next to the shotgun that he is reaching for under the bed.

29 March

It isn’t often that I immediately want to re-read a book I have just finished: The Sixth Lamentation is an exception.

The author, William Brodrick, was a monk who left his order and became a lawyer and then a writer. His background is reflected in the storyline: it is set partly in a priory in the ’90s, where a Nazi war criminal has claimed sanctuary, and is in part also about the ensuing court case. At its heart is a mystery surrounding the betrayal and break-up of an organisation in Occupied France in the Second World War that was smuggling Jewish children to safety.

Part of the reason why I want to re-read The Sixth Lamentation is because it is such a multi-layered novel, with literary allusions and spiritual insights interwoven into an already complex storyline. There is too much going on to sum it up adequately in a few sentences; suffice it to say that the themes of love, duty, sacrifice and forgiveness loom large. The book occasionally threatens to keel over under its own weight — references to Bedivere, one of the Knights of the Round Table, are a bit clunky, for example — but for intellectual daring it brings to mind The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco, though the puff-quote on the front of the book says ‘Worthy of le Carré at his best’. Either way, it’s no mean comparison.

It isn’t made clear but the title is a reference to the book of Lamentations in the Bible, which (as best as I can gather) contains five laments for the destruction of Jerusalem in 586 BCE by the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar. It seems reasonable to assume that ‘the sixth lamentation’ is a reference to the Holocaust.

Books, TV and Films, February 2021

1 February

Age of Empire 1875–1914 is the final part of Eric Hobsbawm’s trilogy about what he called ‘the long nineteenth century’, beginning with the French Revolution in 1789 and ending with the outbreak of war in 1914. I bought this book at university when it was first published in 1987. It follows the same broad approach of the first two volumes, opening with a general economic survey, thus emphasising the centrality in Marxist thinking of economic developments to any understanding of history, before moving on to the social and political scene, culture and ideas etc.

One change, however, is a chapter specifically focusing on women. I remember Hobsbawm commenting on this in interviews at the time, an admission of sorts that the Marxist left had hitherto failed to give due weight to women’s struggle for equality in its historical and political analyses. This lacuna was one aspect of a more fundamental weakness. By the mid-1980s the traditional class-centric perspective was very much under threat from newer voices on the left who could see how capitalism was evolving — particularly the decline of the heavy industrial sector and the shift towards globalisation — and who were keen to embrace conceptions of identity based not just on the workplace but on gender, race and sexuality etc.

Their intellectual home was a remarkable magazine called Marxism Today which, despite retaining its old tagline ‘the theoretical and discussion journal of the Communist Party’, championed a radical new agenda at odds with the (very) old guard of the CPGB and their house newspaper, the Morning Star. Interviewees included the Labour leader Neil Kinnock and even the brash Tory politician Edwina Currie. Despite his seeming indifference to feminism, Eric Hobsbawn was one of the intellectual heavyweights influencing Marxism Today. Even before the election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979, he had given a seminal lecture called The Forward March of Labour Halted? which described how the traditional working class was fracturing.

3 February

The 2020 film The Invisible Man is a very up-to-the-minute take on the classic HG Wells story. The plot revolves around the idea often referred to as ‘gaslighting’, everybody’s favourite insult these days, especially when hurled in the direction of politicians. It is used to mean manipulating someone psychologically so that they end up doubting themselves and even, in extreme cases, reality and their own sanity. The film stars Elisabeth Moss, who seems to have achieved A-list celebrity status following her success in The Handmaid’s Tale, though I know her from twenty years ago as Zoe Bartlet, one of the president’s daughters in (probably) my all-time favourite series, The West Wing.

4 February

Speaking of people doubting reality and their own sanity, Marcella is one of the few drama series that I have watched in real time (as opposed to months or years after it was initially shown). Its central conceit — a highly capable police detective with extreme mental health issues — made for a compelling first series, though, inevitably, the follow-up stretched credibility up to and beyond breaking point.

It seems an age since series two was broadcast. Marcella is now in Northern Ireland, having been rescued from the streets by a shadowy police intelligence unit keen to make use of a talented officer officially registered as dead. I binge-watched the eight episodes over four days, enjoying the drama rather than worrying too much about implausible plot developments.

One wonders how the Maguire family, sufficiently sophisticated, ruthless and well connected to become the pre-eminent crime family in an area with a long and tragic history of troubles, manages to implode within a matter of weeks; or, indeed, why they would allow such a suspicious and manipulative character as ‘Keira’ to live in the family home, the nerve centre of operations, when they clearly have no compunction about bumping off anyone who seems to threaten their status.

Fellow ex-Brookside regular Amanda Burton joins Anna Friel in the cast. Amanda was a primetime regular in Silent Witness in the ’90s but I remember her as the middle-class Heather when Brookside first started in the ’80s. Her performance in the final two episodes of Marcella, following a significant plot twist, is the acting highlight of the series.

10 February

The Odessa File (starring a very young-looking Jon Voight) is one of those ‘classics’ — like Ice Station Zebra and The Heroes of Telemark, both of which I watched recently — that pop up fairly regularly on television, usually on a Saturday or Sunday afternoon. The film is overlong and underwhelming but it’s the novel that I remember, written by Frederick Forsyth, who made his name with the thriller The Day of the Jackal. I read both books probably as a sixth-former, just becoming aware of page-turning novels as an enjoyable way to learn about historical events. Alistair MacLean and Jack Higgins were other writers I read a lot — books like Partisans and The Eagle Has Landed, both set during the Second World War.

12 February

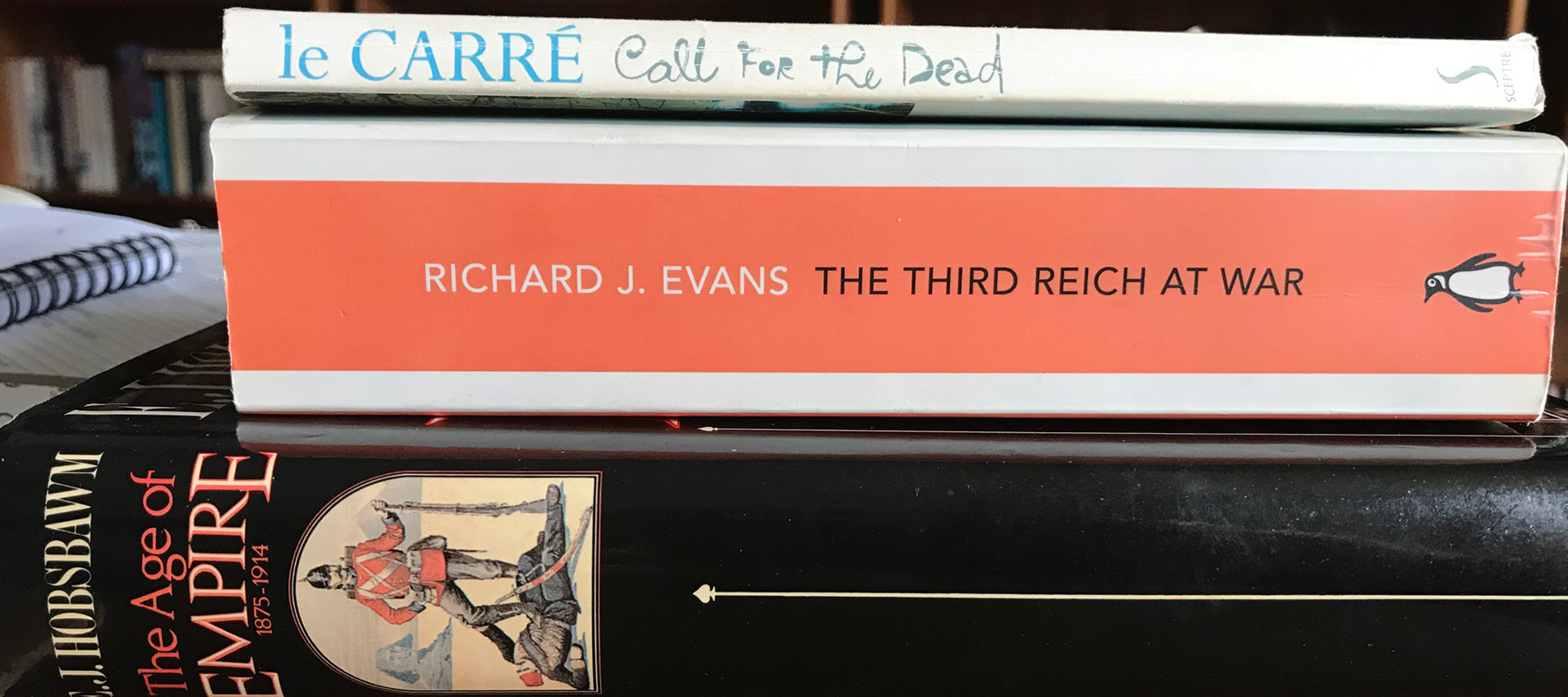

“Short, fat, and of a quiet disposition, he appeared to spend a lot of money on really bad clothes, which hung about his squat frame like skin on a shrunken toad.” This description appears on page 1 of Call for the Dead, the first chapter of which is entitled A Brief History of George Smiley. It was John le Carré’s first novel, published in 1961. The announcement of his death seems as good an excuse as any to read more le Carré.

For some reason I was under the impression that Smiley is only a fleeting presence in this first novel; he is, in fact, its central character. Le Carré didn’t start writing full-time until after the huge success of his third novel, The Spy Who Came In from the Cold; in Call for the Dead he is still finding his way and perhaps reveals a little too much. What I liked so much about Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and Smiley’s People was their depiction of an inscrutable, enigmatic Smiley, at home in the shadowy world of espionage.

13 February

The film Lady Macbeth reminded me of Fanny Lye Deliver’d. Both are good low-budget productions, both are set during key moments in England’s past — the Industrial Revolution and the period of Cromwellian rule respectively — and both explore class and gender relations in times when society was rigidly hierarchical and patriarchal. The main difference is that, in the case of Lady Macbeth, I gradually lost my initial sympathy for the female lead, who is locked (almost literally) in a loveless household with her weak, drink-sodden husband and his dour and domineering father. The clue was in the title, I guess.

14 February

A few years ago the art historian and TV regular Janina Ramirez promoted her BBC Four documentary England’s Reformation: Three Books That Changed a Nation by encouraging her Twitter followers to post pictures of the three books that have most influenced them. I chose The Weirdstone of Brisingamen by Alan Garner, the first book I remember being read to my class at school, when I was about eight; the Complete Sherlock Holmes, which got me through a not very enjoyable school exchange visit to France when I was fourteen; and Hitler: A Study in Tyranny by Alan Bullock, the first full-length history book I read, when I was a sixth-former.

I have been tempted recently to re-read either the Hitler biography — a true classic — or Bullock’s later Parallel Lives, a joint biography of Hitler and Stalin. Both, however, are huge books and I need to read The Third Reich at War, the final part of Richard J Evans’s Nazi Germany trilogy.

20 February

Two more films.

The Rhythm Section starts promisingly. Stephanie is a bright young woman whose life has fallen apart after all her family were killed in a plane crash; we later find out that she should have been on the plane as well and that they were only on that particular flight because of her. An investigative journalist tracks her down to a brothel and reveals that the crash was actually the result of a terrorist bomb. Unfortunately, The Rhythm Section starts to lose its rhythm at this point. Stephanie locates a ruthless and highly secretive ‘off-the-grid’ MI6 agent by typing a postcode into Google Maps. He then trains her to impersonate a dead assassin and soon she is commanding $2 million per hit. Villanelle in Killing Eve does it all with a lot more panache.

I realised after about 20 minutes that I have already seen Child 44, a film about a hunt for a child killer. The selling point (for me) is that it is set in the old Soviet Union, predominantly in 1953 (the year that Stalin died). The film’s hook is that, as the party line was that murder (or indeed any crime) was a capitalist disease and therefore impossible in the socialist paradise, to even conduct a serial-killer investigation was potentially a treasonous act.

It is too simplistic to say that the Stalinist state tried to somehow abolish crime. What was common was criminal behaviour explained away as the result of mental illness or counter-revolutionary activity. Some have also criticised the stodginess of the film and particularly the Russian accents. I found it a convincing depiction of a workers’ anti-paradise in which state power had grown to monstrous proportions, ordinary working people lived lives of fear, often in conditions of abject squalor, and the most active and ruthless criminal of all was the state itself.

26 February

Imagine being a rock music fan just discovering Led Zeppelin or Deep Purple. One of the benefits of never having been a telly addict is that I get to pick and choose from an inexhaustible supply of seriously good programmes from years gone by. The police cold-case drama Unforgotten, for example. Based on the lavish praise heaped on it ahead of the new series, I decided to give it a go. And it is terrific. Each episode is about 45 minutes long. I watched almost a complete series in one Friday evening binge.

They’re up to series four. I can access series two and three from ITV Hub but series one is currently only available via Netflix (which I would have to pay for). That seems annoyingly arbitrary. If ITV are promoting past series of a currently running drama via their on-demand platform, it surely makes sense to make the whole thing available.

So, series two it is. Fortunately, there is no story arc overhanging from the first series. I immediately warmed to the two central characters, DCI Stuart and DI Khan. It’s their ordinariness — the lack of glamour, the absence of power politics, their basic decency and humanity. How refreshing to see them working as a team and treating colleagues with respect, rather than endlessly pulling rank, shouting at subordinates and flying off the handle when an investigation doesn’t go exactly to plan or yield instant results.

28 February

The Third Reich at War has reached 1945. It is still impossible to read about the Second World War without feeling sickened by the enormity of what took place, particularly in eastern Europe — the wanton destruction, the sadistic cruelty, the mass slaughter. Much of it (though not all) was carried out in the name of Germany and, as Richard Evans makes clear, perpetrated by regular soldiers as well as by fanatical Nazis, though to nothing like the same extent. And as Evans also points out, it is inconceivable that millions of ordinary Germans back home were unaware of what was happening, at least in broad terms, once the systematic extermination of the Jews was underway.

The savagery began not with the death camps but as soon as the German army invaded Poland in September 1939 — looting, burning and pillaging, large-scale summary executions, mass killings and so on, carried out not just against Jews but against all those the Nazis deemed inferior. And yet Hitler was never more popular in Germany than in 1940. How quickly and easily a civilised nation, drunk on victory and seduced by lies, had succumbed to barbarism.

In 1943, according to Evans, the Luftwaffe general Adolf Galland reported to Hermann Goering (in overall charge of the Luftwaffe) that he had proof from shot-down pilots and plane debris in Aachen that the Americans had managed to develop fighter planes with added-on fuel tanks, increasing their range. This meant that fighters would now be able to escort bomber planes further into Europe, thus increasing the devastation to Germany’s cities. Goering, who had boasted at the start of the war that not a single enemy bomb would fall on Germany, replied: “I herewith give you an official order that they weren’t there!”

On 6 March 2021, footage circulated on Twitter with the caption: ‘Parents encouraging kids to burn masks on Idaho Capitol steps’. This may or may not be an isolated incident, but there is no doubt that we are once again living in the West in an age when cranks, firebrands and demagogues are no longer on the forgotten fringes but part of mainstream political debate. Millions of people are again prepared to follow leaders who have little or no regard for science, objective truth and reasoned argument; who attack the pillars of an open, just and tolerant society such as free and fair elections, an independent judiciary and investigative journalism; and who peddle conspiracy theories and preach bigotry and intolerance.

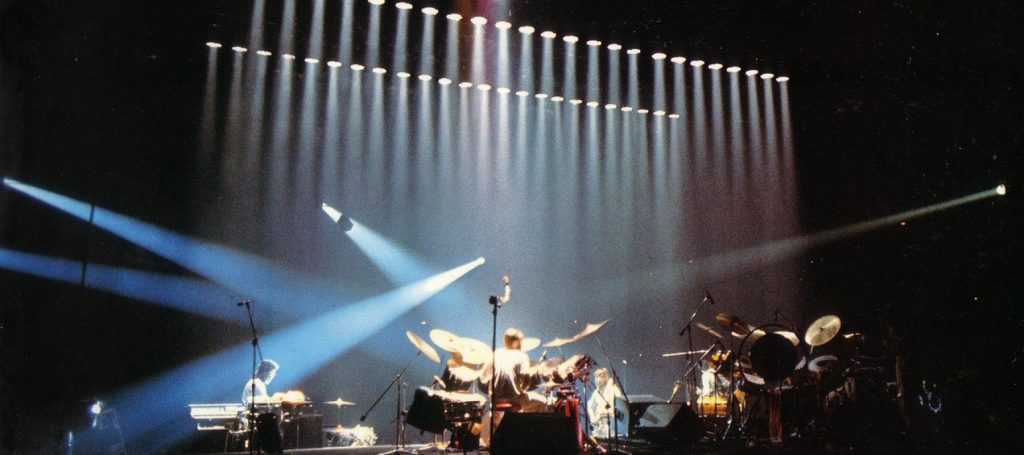

Frankfurt 1981: Genesis Bootlegs

I blame Peter.

Or maybe Hugh.

No. Perhaps it’s all Phil’s fault.

That’s Peter Gabriel, Hugh Padgham and Phil Collins.

Blaming them for what exactly? Well, that drum sound for starters, known as a ‘gated’ or ‘gated reverb’ sound, apparently. It was a big (in more than one sense) part of the transformation of Genesis as they followed a new chart-friendly formula at the start of the new decade. And it wasn’t just the Genesis sound that radically changed. The writer Stuart Maconie (quoted on Wikipedia) described Phil’s use of the gated drum sound on his first solo single as “setting the template”; another writer (also via Wikipedia) called it “the sound of the ’80s”.

And all, it seems, a happy accident. Phil was helping Peter with his third album (‘Melt’). Peter didn’t want to use any cymbals at all. Hugh, the engineer, was therefore able to place the mics much closer to the drums than normal. A few tweaks of various knobs and, hey presto, the booming drums of Intruder kicked off Peter’s highly acclaimed album (the first one of his I bought, on the back of a great review in Sounds, and still a favourite). Fast-forward a few months, and Hugh and Phil try to recreate the sound for Phil’s solo song In the Air Tonight. Forty years, and the occasional gorilla, later and it still packs a mighty punch.

Hugh was also on board as engineer for the new Genesis album. The Duke sessions had already seen a fresh approach to writing — more collaborative, more spontaneous. This method was taken further with the new album. Tony, Phil and Mike contributed just one individually written song each; the others were all studio creations.

With Padgham on board, it wasn’t just the drums that sounded different. I hated the Abacab artwork at the time, but there’s no doubt that it neatly encapsulated the music it housed: bold, brash, stark. It was also abstract — as abstract as the title track, a gibberish word made up of letters representing an early arrangement of the song. As Tony said, this is not an album with lyrics about goblins and fairies.

To say that I loathed the music as well as the cover would be going too far. Genesis were certainly not the only ’70s band to be modernising their sound at the start of the new decade, and the first 30 minutes of Abacab are enjoyable enough.

The title track bursts in like a surprise guest and, like many good album openers, sets the mood for what is to come; the second half of the song, meanwhile, is more of a leisurely (if somewhat unadventurous) jam, with plenty of space in the soundscape for instruments to breathe.

Keep It Dark has an experimental quirkiness about it. No Reply at All — with its Earth Wind and Fire horns — is distinctly un-Genesis and, as such, bound to divide opinion, but it’s catchy and has a great middle eight. Me and Sarah Jane (Tony’s song) is probably the closest thing to ‘typical’ Genesis and perhaps the best track on the album, along with Dodo/Lurker which opens the original side two.

At this point, however, there is a startling drop-off in quality. The final third of the album lacks sparkle and ends, with Another Record, on a decidedly downbeat note. Of Who Dunnit?, more below.

The album was released in September 1981. Looking back, Tony, Mike and Phil seem to emphasise the album’s importance (Phil, in Chapter and Verse: “This gave us a genuine reason to carry on…”) rather than its quality. Tellingly, none of its songs featured on the 2007 reunion tour. And it certainly divided fans at the time: at their show at Leiden in Holland, for example, the new songs were loudly booed. But whatever the views of long-time Genesis fans, the wider public seemed to like the new direction, at least judging by record sales — it was Number One in the UK and sold more than two million copies in the USA. The commercial success of both single and album cemented Genesis’s place in the big league.

Concerts in mainland Europe to coincide with the album’s release were followed by a tour of North America and then shows at Wembley Arena and Birmingham NEC just prior to Christmas. A live double album was released six months later.

I have written elsewhere that Seconds Out, recorded primarily on the Wind and Wuthering tour in 1977, is one of the great live albums. It is safe to say that Three Sides Live isn’t. The album did much at the time to strengthen my misgivings about this ‘new’ Genesis, in part perhaps because it is such a difficult album to categorise and ends up trying to offer something for everyone. It suggests that the band themselves were unsure about how far to push their new sound and still wrestling with the ongoing conflict between what Phil was now regularly referring to as “old shit” and “new shit”.

The original sides one and two are a somewhat random and randomly organised selection of highlights from the Duke and Abacab albums. The combination of Behind the Lines and Duchess was an effective show opener on the Duke tour, though here relegated to side two. Similarly, Dodo/Lurker and Abacab were live highlights from the current tour.

Turn It On Again, a big audience-widening hit, opens side one, even though it actually featured towards the end of the main set. Misunderstanding and Follow You Follow Me (the latter from the Duke tour, as it was dropped for the Abacab tour) ratchet up the singles quotient. The outlier is Me and Sarah Jane, a standout track from the Abacab album but hardly a live showstopper. Much of side three is given over to the medley of old songs, ending with Afterglow, the only song also to feature on Seconds Out.

And then the bizarre side four. The UK iteration of Three Sides Live featured three apparently randomly chosen classics, as played in 1976, 1978 and 1980 — a pattern of sorts there at least. The closing it. / Watcher of the Skies, the encore on the Trick of the Tail tour, thus features both Steve Hackett and Bill Bruford. The rest of the world, meanwhile, got a compilation of the recent single Paperlate and some non-album b-sides — hence the album’s title.

Random, indeed. One thing Three Sides Live did have in common with Seconds Out: it misrepresented the Genesis show. The set list for the 1981 legs of the Abacab tour was as follows:

Behind the Lines / Duchess /

The songs shown crossed through were not included on Three Sides LiveThe Lamb Lies Down on Broadway/ Dodo/Lurker /Abacab /Carpet Crawlers/ Me and Sarah Jane / Misunderstanding /No Reply at All/Firth of Fifth/Man on the Corner/Who Dunnit?/ In the Cage / The Cinema Show [excerpt] / The Colony of Slippermen [excerpt] / Afterglow / Turn It On Again /Dance on a Volcano/Los Endos/I Know What I Like

The outstanding bootleg from the Abacab tour is from Frankfurt on 30 October. It is astonishingly good, an absolute must-have for any Genesis fan’s collection. It demonstrates that Genesis hadn’t suddenly become a crap band, even for those of the opinion that the new album was very much heading in the wrong direction, and that the show as a whole retained a reasonable balance between older and newer material, a fact that wasn’t obvious from Three Sides Live.

Long-time favourites such as The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway (restored to the set after a four-year hiatus) and Carpet Crawlers still sound great. Firth of Fifth also returns, this time of course with Daryl in the spotlight rather than Steve. Fans of ’70s Genesis are unlikely to bemoan a set list liberally studded with gems of old; on the other hand, despite a back catalogue bulging with crown jewels, much of it remains locked away in the vaults. The In the Cage medley, augmented for this tour with the keyboard solo from The Colony of Slippermen, is now on its third journey round the world. The close of the show — Dance on a Volcano, the drum duet and Los Endos, ending with an encore of I Know What I Like — also feels more than a little familiar.

Unsurprisingly, there is more of an ’80s vibe or sensibility about all of these revisited classics. There’s Phil’s ad lib during The Lamb, for example: “I’m not your kind, bitch — I’m Rael!” And then there’s the shoutier, more aggressive vocal during songs like Man on the Corner and I Know What I Like. Or perhaps it’s just that Phil’s singing voice, like his on-stage persona, has simply become harsher and raspier after years of touring.

Phil’s monologues seem to be getting longer, and maybe it’s to do with the larger venues on this tour but the between-song chatter generally feels less playful; the introduction to Man on the Corner at Frankfurt — “Everybody thinks he’s a bit stupid” — isn’t funny at all. There’s plenty of the usual Carry On-style slapstick but, as noted in the reviews of the earlier tours, some of it hasn’t aged at all well, like the description (at the final show at Birmingham) of Cindy Lou as a “beautiful young tart” and comments like “the good things in life — necrophilia, bestiality, incest, rape.”

The new album features heavily — six tracks. As noted above, the standout live tracks are probably Dodo/Lurker and Abacab, played back to back in one fifteen-minute burst. Less successful are No Reply at All, minus the horn section, and to a lesser extent Me and Sarah Jane, neither of which was retained for the following tour.

The low point, however, comes mid-show — a mediocre Man on the Corner, whose mysterious subject is not so much standing around as wandering aimlessly towards a downbeat drum-machine destination, abruptly morphs into Who Dunnit? Watching Tony Banks, a naughty gleam in his eye, discuss the song is to imagine him back at Charterhouse, refusing to apologise to the house master for some minor act of teenage rebellion, like drawing a willy on a textbook or turning up for class with a shaved head. Who Dunnit? is awful but Tony doesn’t care. It’s his punk moment.

Following the release of the Three Sides Live album in June 1982 (and an accompanying film), the band toured again with a revamped set.

Dance on a Volcano / Behind the Lines / Follow You Follow Me / Dodo/Lurker / Abacab / Supper’s Ready / Misunderstanding / Man on the Corner / Who Dunnit? / In the Cage / The Cinema Show [excerpt] / The Colony of Slippermen [excerpt] / Afterglow / Turn It On Again / Los Endos / The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway / Watcher of the Skies / I Know What I Like

Dance on a Volcano is back opening the set for the first time since 1976. Another highlight is an extended bridge between The Lamb and Watcher of the Skies. The most eye-catching change, however, is the return of Supper’s Ready (along with the two virgins, Romeo and Juliet), played for the first time since 1977. It features on a very good bootleg of part of the Saratoga Springs show on 26 August. The performance itself is terrific too, in spite of Phil’s silly Mexican/Spanish ad libs during the Willow Farm section. One wonders whether this was the origins of (the now rather cringe-inducing) Illegal Alien on their next album, in the same way that Paperlate is said to have emerged out of soundchecks of Dancing with the Moonlit Knight.

In early October the five touring members of Genesis joined with Peter Gabriel for the one-off Six of the Best concert at Milton Keynes to raise money following the commercial failure of the first WOMAD festival which left Peter facing financial ruin. Steve Hackett joined them on stage for the encores. It was a nostalgic — and final — reprise of ‘old’ Genesis. The following year was to see even greater commercial success for the band and the beginnings of global superstardom for Phil as a solo artist.

Books, TV and Films, January 2021

2 January

A fantastic way to kick off the new year — Bring Up the Bodies, the second volume of Hilary Mantel’s fictional account of the later life of Thomas Cromwell, the architect of much that went on in the name of Henry VIII in the 1530s. This volume focuses on the events of 1535–6, particularly the fall from favour of Anne Boleyn and Henry’s courtship of Jane Seymour.

Lacking in-depth knowledge of Tudor politics, I found Diarmaid MacCulloch’s acclaimed biography of Cromwell tough going at times. Historical fiction — the well-written variety — can be a friend to the uninitiated, an entrée into worlds only dimly understood. As well as requiring encyclopaedic knowledge and command of the sources, the writing of historical fiction takes a different approach to that of the historian or biographer and requires a different skill set. There is, for example, no room for ‘possibly’, ‘probably’, ‘maybe’, ‘on balance’. It is, in part at least, history of the imagination. And Hilary Mantel is a master of the form. The Mirror and the Light, the third part of the trilogy, awaits.

7 January

And so to Revolution, the 1980s film starring Al Pacino and directed by Hugh Hudson (of Chariots of Fire fame). It was shown on a fairly obscure channel and was not an easy watch. The two things may be linked. There was some narration from the Pacino character but it was still difficult at times to follow the wildly improbable story, which spanned the years of the American War of Independence. The dull sound certainly didn’t help; nor did Pacino’s odd accent and mumbled delivery. I read that there was a director’s cut released in 2009. Surely that can’t be the version I watched.

Yesterday was the day when a Trumpian mob descended on Washington DC’s Capitol building in an attempt to overturn the result of the presidential election. One of the protesters referenced the events of 1776 in an attempt to justify the mob’s actions, as if America’s essence is forever defined by conflict and upheaval. What dangerous nonsense.

For all its faults, Revolution reminds us that war is not noble and cathartic but bloody and savage. It depicts cruelty, inhumanity and stupidity on both sides, with men and women struggling to survive amidst squalor and filth. Yorktown, scene of a pivotal battle in 1781, is shown as little more than a hilltop, defended by a hastily thrown together collection of flimsy barricades.

10 January

BBC Four is repeating The Night Manager, the brilliant adaptation of the novel by John le Carré that was first shown in 2016. It’s their tribute to le Carré, who has of course recently died. I first read a book-club edition of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy as a sixth-former, recovering from a hernia operation. Leaving aside the likes of Stephen King and James Herbert, it was — along with Animal Farm and 1984 — one of the first ‘serious’ novels that I really enjoyed.

The Spy Who Came In from the Cold is probably my favourite, but each le Carré book is both a masterclass of intelligent writing and a puzzle to unravel. Yes, there are layers I am not penetrating, references I am not understanding, nuances I am not appreciating. That’s why it’s no hardship to pick any of them off the shelf to re-read. Not to mention the ones that I have still to tackle for the first time.

12 January

Steven Pinker is one of those individuals sometimes described as a ‘public intellectual’. Richard Dawkins is another. In Dawkins’ case it was perhaps in part because at one time his position at Oxford was as professor for the public understanding of science. As for Pinker and people like Michael Sandel (the ‘public philosopher’), it seems to be a term that gets attached to someone who is erudite and highly qualified but also engaging to listen to and able to communicate complex and challenging ideas in an accessible way.

Pinker isn’t always the most fluent of speakers (a few too many ‘aahs’ in conversation and an annoying tendency to read out his PowerPoint slides during presentations) but he writes beautifully. I am currently reading his book about writing, The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century. It is much more than a dry manual of grammar and punctuation, though Pinker includes plenty of helpful tips, pointers and explanations in the final — and longest — chapter.

A key point he makes is that (in English at least) there is no equivalent of the Highway Code that sets out hard and fast rules on usage. Nor is there an all-knowing, all-powerful “tribunal of lexicographers” (his phrase) issuing decrees from on high. Instead, the prescriptive rules that we follow are tacit conventions, accepted by the overwhelming majority of literate people to ensure clarity and prevent misunderstandings or simply in the interests of elegance and style. And many of the ‘rules’ we follow (such as not starting a sentence with ‘and’ like I just did) are nothing more than the equivalent of old wives’ tales with little or no basis in logic.

I will certainly be closely studying (or should that be ‘studying closely’?) the sections dealing with grammar and syntax. Much of my understanding of language came from learning Latin as a teenager, though with no formal training in grammar itself I am like a musician who plays by ear rather than by reading music. I can usually sense a problem with a piece of writing without necessarily being able to explain in grammatical terms what the problem is.

Pinker also brings his expertise in cognitive science to help the writer understand not just how to write elegantly but also how to maximise the reader’s understanding, and his chapter on ‘the curse of knowledge’ is an eye-opener for anyone writing for a non-specialist audience.

I find writing an arduous process — a struggle even on good days and free from the tyranny of deadlines — so it was reassuring to read Pinker’s description of how he writes:

I rework every sentence a few times before going on to the next, and revise the whole chapter two or three times before I show it to anyone. Then, with feedback in hand, I revise each chapter twice more before circling back and giving the entire book at least two complete passes of polishing. Only then does it go to the copy editor …

Steven Pinker, The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century

19 January

Some — though by no means all — of the historian EP Thompson’s thoughts on political theory and left politics might be past their sell-by date, but the writing itself is still fresh. The Poverty of Theory is a collection of four (in)famous long essays. First up is The Peculiarities of the English, written in 1965. How about this for an extended metaphor:

Our authors [Perry Anderson and Tom Nairn, whose work he is critiquing] bring to this analysis the zest of explorers. They set out on their circumnavigation by discarding, with derision, the old speculative charts … But our explorers are heroic and missionary. We hold our breath in suspense as the first Marxist landfall is made upon this uncharted Northland. Amidst the tundra and sphagnum moss of English empiricism they are willing to build true conventicles to convert the poor trade unionist aborigines from their corporative myths to the hegemonic light.

EP Thompson, The Peculiarities of the English

23 January

Having really not enjoyed reading Lesley-Ann Jones’ biography of Freddie Mercury recently, I have gone back to a book I cited in my review of it as an example of good writing, Mark Blake’s Is This the Real Life? The Untold Story of Queen. Well, I will certainly be revising my wording if the opening chapter is anything to go by.

- Blake states that Mel Smith and Griff Rhys Jones introduced the band to the stage at Live Aid at 6.44pm. An on-stage clock visible at the start of Radio Ga Ga (ie the second song) shows the time as 6.44pm. The time usual given for the start of Queen’s performance (eg on disc 2 of the Queen at Montreal dvd) is 6.41pm. It might seem a trivial point except that the writer himself chooses to give a precise time. If doing so, at least get the facts correct.

- He describes Freddie’s piano as being stage left. It is stage right, using standard stage directions (ie left and right are from the perspective of the performer looking out at the audience).

- This, on page 4, isn’t even a sentence: “But its promo video, with scenes lifted from the 1920s sci-fi movie Metropolis, which helped to sell the song.”

There’s plenty more, just in the opening chapter.

25 January

The Night Manager was quite superb — high-end production values, sumptuous locations befitting a seriously wealthy arms dealer, great performances from the likes of Hugh Laurie and Olivia Colman. And, above all, the plotting. This might not be served up as Cold War fare, but all the familiar Le Carré ingredients are there — bravery, compromise, betrayal, with a tasty side dish of moral ambiguity and general murkiness.

And now another treat — All the President’s Men, the 1976 film of the investigation by Washington Post journalists Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein into the Watergate break-in, which ultimately led to President Nixon’s resignation. The film doesn’t try to tell the whole story. Anyone hoping for a detailed exposé of the corrupt networks spreading out from the Oval Office should look elsewhere.

This is a film about investigative journalism in its prime, about how good reporters go about their work even in the most intimidating and claustrophobic of circumstances. The film adopts a realist approach in depicting the hurly-burly of Woodward and Bernstein’s investigation at the Post’s massive open-plan office — cross-talking and interrupted dialogue, incidental and inconsequential detail, lots of background noise. It’s like a fly-on-the-wall documentary years before the genre really took off.

The film is also wonderfully atmospheric — the shadowy parking lot where Woodward meets Deep Throat, the flag on the balcony they use to secretly communicate, the shuffling and mumbling of countless nervous interviewees, terrified of being seen speaking to journalists.

With press freedom under threat as never before, All the President’s Men is a must-watch.

28 January

The Mark Blake Queen biography continues to underwhelm — from ‘well written’ to ‘decently written’ to ‘decently written, at least in part’. Shoddy proofing and the occasional egregious cliché apart, the main problem is that, like the Lesley-Ann Jones book, it loses its shape once the narrative reaches the point at which Queen had reached ‘rock star’ level — 1977, say.

Take this paragraph, typical of the second half of the book:

Taylor and Mercury would see out the summer of 1979 enjoying all the perks of moneyed rock stardom. They were among the spectators watching Bjorn Borg win the men’s singles final at Wimbledon … Later, Taylor and Dominique Beyrand holidayed in the South of France. On the drive down to St Tropez, the engine on Taylor’s new Ferrari blew up, rendering the car a wreck (a similar fate would befall his Aston Martin). In September, Mercury celebrated his thirty-third birthday with another lavish soiree and began plotting his next career move.

Mark Blake, Is This the Real Life? The Untold Story of Queen

It reads like a chronicle, detailing one fact or event after another. A generous reader might argue that the opening sentence frames the paragraph — Roger and Freddie enjoying the good life. But what about Brian and John? Where are they? Were they not “enjoying the perks of moneyed rock stardom”? That opening sentence is more like a convenient hook on which to hang some random facts. And what’s this nonsense about a “next career move”? Freddie was preparing for a one-time performance with the Royal Ballet Company. He performed two songs. That’s it.

I read the final 100 pages of the book in under three hours. There was little or nothing to hold the reader’s attention, just a collection of details, many of which — far from being ‘untold’ — are readily accessible for even the most casual of fans from other sources.

29 January

As a devotee of the original Conan Doyle books, I am usually reluctant to engage with the seemingly endless new interpretations of the Sherlock Holmes stories and characters. The first series of Sherlock, set in the modern day, was fabulous — wonderfully creative and full of fun — but later episodes became increasingly ridiculous. Robert Downey Jr’s swashbuckling Holmes was enjoyable, though equally ridiculous. I always steer well clear of spoofs.

It was a delight, then, to watch a very different iteration of the great detective in the film Mr Holmes. Ian McKellen stars as the detective in extreme old age, having retired almost 30 years earlier to keep bees in Sussex.

This is a gentle and wistful Holmes, who has lost almost everything of importance to him. His few significant others are dead — Watson (referred to throughout as ‘John’) and Mrs Hudson. Now his memory, too, is fading fast. He is aware that his final case must have ended in failure — hence the decision to retire — but can no longer remember the details except for the knowledge that the version penned by Watson is false. Two backstories are woven into the storyline, as the eminent logician and scientist is brought face to face with the one great chink in his armour — his lack of humanity.

McKellen is excellent as both the dashing sixty-something detective and the fragile nonagenarian. Children in leading roles are often a weak link but Milo Parker is terrific as the housekeeper’s young son, Roger, whose intellect and curiosity help to reignite Holmes’ own. I love Laura Linney but she is a rather curious choice for the part of the widowed housekeeper — “of no fixed accent,” to quote the film critic Mark Kermode. That made me chuckle.

Books, TV and Films, December 2020

1 December

Straight in at Number One on my reading list goes A Promised Land, the first volume of Barack Obama’s memoirs. Just a quick word on the cover price — a wallet-busting £35 (selling at half price in Asda). It’s said that the Obamas negotiated a book deal in the tens of millions of dollars. Michelle Obama’s book, Becoming, was a worldwide bestseller. I am sure that the publishers are expecting something similar from A Promised Land, but, even for a volume running to 700-plus pages, the cover price is seriously off the charts.

3 December

The Homesman is a remarkable film. Set in the 1850s, it shows the harsh, bleak reality of the American West and the meaning of rugged individualism. I suppose it might be called ‘revisionist’. It is certainly nothing like the sanitised westerns on which my generation grew up.

At the centre is a compelling character called Mary Bea Cuddy, played beautifully by Hilary Swank. An intelligent, hard-working, pious and fiercely independent woman, she volunteers to undertake a long and dangerous journey to transport three mentally ill women to a place of refuge. She longs to find a man to marry, only to be rebuffed as plain and bossy when she raises it with a potential (though, frankly, unsuitable) candidate. To hear her repeat almost the exact-same proposal to a second, equally unsuitable, individual later in the film is heartbreaking.

8 December

I picked up the Obama book not knowing quite what to expect. I was aware that he has published other books, and so I was unsure how much of a ‘Life’ A Promised Land would be. The answer is: not much. There are details about his childhood and early adulthood, including Harvard Law School, and his time as a state senator in Illinois and then a US senator, but it is all somewhat sketchy. By page 80 he is running for the presidency.