Brexit, the 2019 Election and the State of British Politics

For someone who locates himself somewhere on the political left, the outcome of the 2019 general election was shattering and sobering, though surely not entirely unexpected: a substantial Commons majority for the Conservatives — memo to self: look up the definition of ‘landslide’ — and, what is worse, talk of ‘powerful’ mandates, ten years of Conservative rule and a ‘Boris revolution’. Note: this is the sole reference to ‘Boris’ and deliberately placed in inverted commas.

Unfortunately, election promises — especially Johnson promises — are, like many Christmas toys, cheaply made and easily broken.

Diogenes

It is possible that Johnson’s large parliamentary majority and the largesse promised to, and seats secured in, formerly solid Labour areas will free him of the urge to tack to the right in order to satisfy the whims of erstwhile ERG allies. Unfortunately, election promises — especially Johnson promises — are, like many Christmas toys, cheaply made and easily broken. We will know more after Javid’s next budget (expected in February 2020) and the forthcoming multi-annual spending review, but the early signs do not augur well.

The revised EU Withdrawal Agreement largely stripped away previous guarantees of workers’ rights, regulatory standards compliance and parliamentary scrutiny. Meanwhile, though a New Year’s Eve announcement of a 6.2% increase in the minimum wage is welcome, earlier promises to increase the minimum wage to £10.50 over five years now come with a small-print caveat — “provided economic conditions allow”.

The Labour Party in 2019 faces a threat to its existence as grave as that of 1979-83. The loss of heartland seats such as Bolsover is historic …

Diogenes

Chapter 22 of (probably) my favourite set of political memoirs — Denis Healey’s The Time of My Life — covers the years after Margaret Thatcher’s election in 1979: he called it Labour in Travail. The Labour Party in 2019 faces a threat to its existence as grave as that of 1979–83. The loss of heartland seats such as Bolsover is historic, though we don’t of course yet know if this represents a permanent shift in the political tectonic plates.

The facts and figures are not encouraging for Labour supporters. Since Harold Wilson’s 98-seat majority in 1966 — 53 years ago, at the time of writing — Tony Blair is the only Labour leader to be elected with a parliamentary majority. Assuming that the Fixed-Term Parliaments Act is repealed, Labour’s next realistic chance of forming a majority government is likely to be 2028 at the earliest, 23 years after Blair’s last victory in 2005. How we lefties hooted in 1997 when the Conservatives were wiped out in Scotland, with Labour winning 56 of the 72 seats. In 2019, Labour won just a single seat out of the available 59.

The first time I didn’t vote Labour — I usually do, with a greater or lesser degree of enthusiasm — was my first general election in 1987. A student at Reading University (which is actually in the Wokingham constituency), I voted tactically for the SDP–Liberal Alliance candidate, defiantly denting John ‘Vulcan’ Redwood’s 20,000-ish Conservative majority by one.

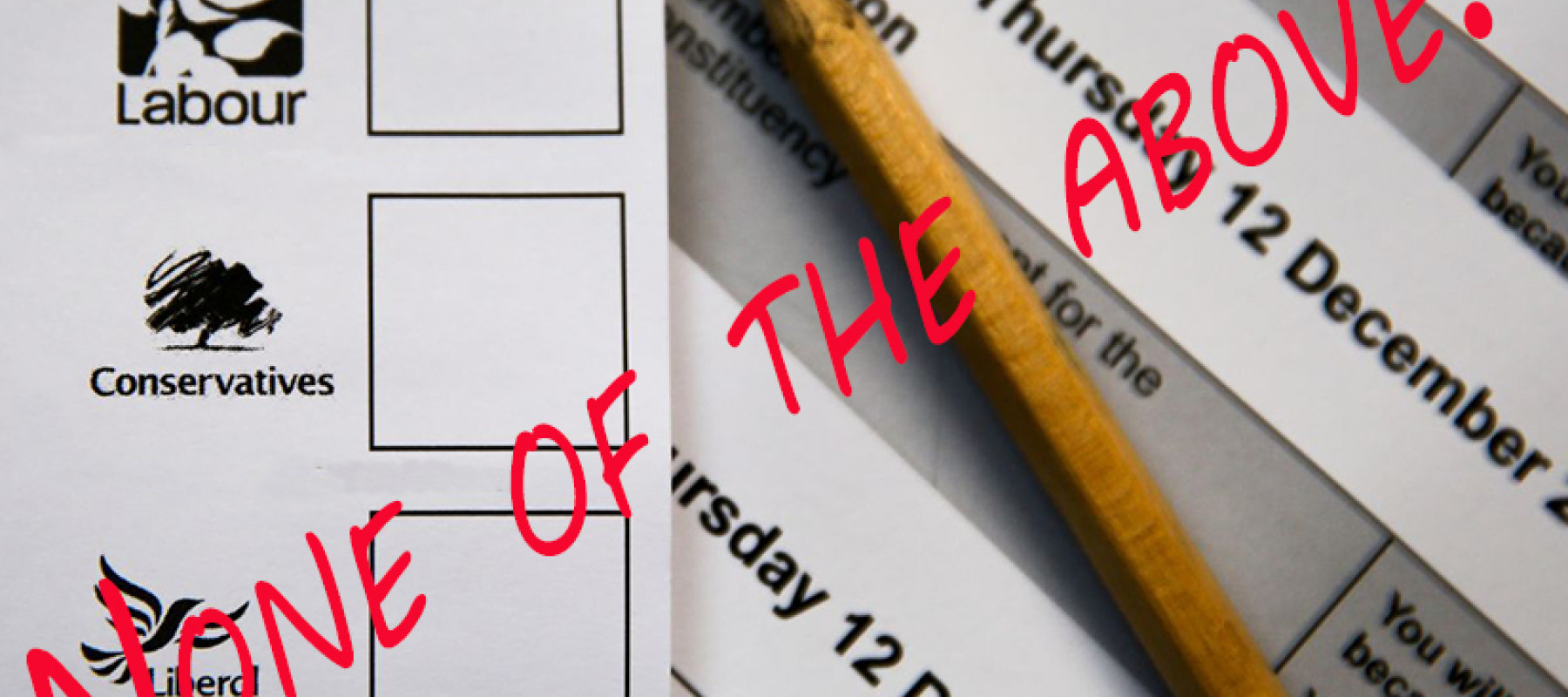

December 2019 was the latest time that X didn’t mark the spot. I certainly wasn’t the only wandering voter, though I doubt too many people joined me in spoiling my ballot paper by scrawling None of the above. Bring back Tony Blair across it.

The influence of the media

Anti-Corbyn or anti-Labour media bias as an explanation for Labour’s defeat — the term ‘media’ used here to refer to the highly regulated broadcast media, the privately owned print media and social media, which is largely unregulated — lacks plausibility.

It is platitudinous to argue that howls of anguish from both sides means that the BBC has ‘got it about right’. Equally, the claim of overt broadcaster bias is risible …

Diogenes

For every complaint about an anti-Labour agenda or a bias against Corbyn, the attack-dogs of the right make exactly the opposite charge about the broadcast media — though not, of course, about the print media — particularly about the BBC. It is platitudinous to argue that howls of anguish from both sides means that the BBC has ‘got it about right’. Equally, the claim of overt broadcaster bias is risible, from whatever quarter it comes.

Andrew Neil’s skewering of Corbyn needs to be seen alongside the same broadcaster’s no-holds-barred interviews with other party leaders and particularly his five-minute empty-seating of Johnson. Andrew Marr’s fussy interview with Johnson generated 12,000 viewer complaints (some, at least, no doubt submitted at the behest of CCHQ).

For all the accusations of an institutional liberal-left bias at the BBC, we should remember that there are plenty of former Conservative Party personnel who hold key positions in the organisation. I wonder what Sarah Sands and Nick Robinson — both formerly prominent Conservative supporters — think of the (probably) Dominic Cummings-inspired boycott of the Today programme by senior ministers.

Perhaps doubters from both sides need to be force-fed an hour of Fox News.

The print media, meanwhile, has always been overwhelmingly anti-Labour in modern times. When, in 1992, a Sun front-page headline requested that the last person to leave Britain in the event of a Labour victory switch off the lights, the paper was selling around 4 million copies per day compared to around 1.4 million in 2019. Newspapers and their owners still wield influence, of course — it is a worry, for example, how much the daily television news agenda is influenced by newspaper headlines — but influence in what circles?

Social media feeds on our algorithmically determined preferences and prejudices, generating sensationalist soundbites and clickbait headlines, devoid of context or even of meaning. Lies are peddled as fact; ludicrous assertions are left unchallenged, bouncing around the echo chamber.

Diogenes

Many ‘ordinary’ voters — as opposed to political geeks and those who inhabit the Westminster bubble — increasingly consume their news via social media rather than from newspapers or TV news. Sadly, this is almost certainly damaging our political culture. Social media feeds on our algorithmically determined preferences and prejudices, generating sensationalist soundbites and clickbait headlines, devoid of context or even of meaning. Lies are peddled as fact; ludicrous assertions are left unchallenged, bouncing around the echo chamber.

But there is no reason why this development — good or bad — should disadvantage the Labour Party over and above their rivals: if anything, social media demographics ought to work in Labour’s favour. An excellent media analysis in the Guardian quoted Dr Richard Fletcher of the University of Oxford’s Reuters Institute: “One of the clearest differences is that most of those on the left prefer to get news online, and most of those on the right prefer to get it offline.”

But social media benefits those with the best lines, and in 2019 the best line of all consisted of just three words: Get Brexit Done.

Brexit

One Friday evening sometime during one of Theresa May’s parliamentary debacles — it’s impossible to pinpoint the specific one; there were so many — a brief pub conversation with a friend of a friend about the dismal performances of our local football team somehow strayed into Brexit territory. That I should be discussing politics at the bar of my local with someone I barely know is itself an indication of the extent to which Brexit weaves its malign magic.

And yet this shameless hyperbole was offered up so calmly, so matter-of-factly, as if pointing out a plain, unremarkable, common-sense fact along the lines of night following day, Saturday following Friday.

Diogenes

I was dumbfounded to hear him — an ordinary, unassuming chap in his seventies: friendly, mild-mannered, level-headed — assert that we (the British people) have been slaves for 40 years — yes, slaves. Stunned by this, my immediate reaction was ridicule, to mimic walking around as if lugging a ball and chain. And yet this shameless hyperbole was offered up so calmly, so matter-of-factly, as if pointing out a plain, unremarkable, common-sense fact along the lines of night following day, Saturday following Friday.

The issue of Britain’s relationship with Europe has obsessed the political classes since the days of ‘splendid isolation’ and long before; most ‘ordinary’ people, on the other hand, have been completely uninterested except, obviously, in times of war. An Ipsos MORI poll conducted during the 1992 general election campaign — the year of the Maastricht Treaty — asked voters to identify their top two or three issues of concern: 4% cited Europe and 1% cited immigration. As recently as 2010, an Ipsos MORI analysis of that year’s general election suggests that, though 14% cited asylum / immigration as a key issue, Europe was not one of the sixteen issues that registered at least 3%.

… the impact of Brexit on the Conservative Party has in some respects been at least as transformative, not to say revolutionary, as the leadership of Margaret Thatcher.

Diogenes

The Europe question has bedevilled both main political parties — it was Labour’s Harold Wilson who called the referendum in 1975, suspending collective cabinet responsibility for the campaign’s duration in an attempt to keep the party together — but the impact of Brexit on the Conservative Party has in some respects been at least as transformative, not to say revolutionary, as the leadership of Margaret Thatcher.

Anti-EU zealots, long in the wilderness, now wield significant influence at the highest levels, including in Cabinet. The Conservatives’ Brexit strategy over the last three years has placed severe strains on our constitutional arrangements and conventions. Moderates such as Ken Clarke and Dominic Grieve have effectively been cast adrift, some even expelled from the party. Astonishingly, during the election campaign, a former Conservative prime minister and deputy prime minister — John Major and Michael Heseltine respectively — urged voters to vote tactically against official Conservative candidates, with Major earlier threatening to take the Conservative government to court.

Listening to the government’s repeated insistence on the need to leave the EU single market in order to forge new trade deals around the world, it is worth remembering that Conservatives’ Euro-scepticism (as it used to be termed) was always political in origin and nature rather than economic — hostility to what they saw as the federalist project of ever-closer union. It was, after all, Margaret Thatcher who negotiated the Single European Act in the 1980s that paved the way for the single market and, though this is seldom mentioned in Thatcherite circles, monetary union.

In an interview with Sky News as recently as 2013, Boris Johnson said: “I’d vote to stay in the single market. I’m in favour of the single market.” In the same year, arch-Brexiteer Andrea Leadsom said that leaving the EU would be “a disaster for our economy and it would lead to a decade of economic and political uncertainty at a time when the tectonic plates of global success are moving.”

Suddenly, any such ‘Norway-style’ arrangement keeping Britain in or closely aligned to the single market has become a betrayal. This post-referendum Conservative and Unionist government — to give the party its full title — has also agreed a Withdrawal Agreement that puts in place separate customs arrangements for Northern Ireland. This is despite Johnson specifically and unequivocally denouncing the idea at the DUP annual conference in 2018.

Without doubt, the government’s Brexit policy has already severely weakened the Union and could potentially lead to its break-up. The Conservative Party of old used to accuse the left of constitutional vandalism: they, by contrast, posed as guardians of the integrity of the United Kingdom.

No longer, it seems. According to a YouGov poll in June 2019, a clear majority of Conservative Party members are prepared to countenance the break-up of the Union in order to achieve Brexit — 63% with respect to Scotland and 59% with respect to Northern Ireland. Extraordinary stuff.

From nowhere, Europe — more specifically our relationship to it — has become an existential issue for the general public, as bizarre and irrational in the visceral reactions it generates as arguments over religion in days of old …

Diogenes

But Brexit has spread its poison far beyond the Conservative Party. From nowhere, Europe — more specifically our relationship to it — has become an existential issue for the general public, as bizarre and irrational in the visceral reactions it generates as arguments over religion in days of old, when disagreements over such arcana as consubstantiation and transubstantiation, and justification by deeds or by faith alone, were often literally a matter of life and death.

Rather than healing divisions, as David Cameron had naively hoped, the legacy of the referendum has been three years (and counting) of anger, frustration and bitterness and, if claims that this was ‘the Brexit election’ are perhaps overstated — at least to the extent that issues such as health, the climate crisis and leaders’ trustworthiness were also widely debated — there seems little doubt that Brexit swayed many people’s vote.

… ‘Brexit’ stands, at least in part, as a proxy for other issues — from concrete concerns about immigration, about job insecurity and poverty, and about haves and have-nots to less tangible feelings of displacement and disconnect, of unease in changing times and of dissatisfaction with our political institutions.

Diogenes

On the reasonable assumption that people don’t deliberately vote to make their country poorer, ‘Brexit’ stands, at least in part, as a proxy for other issues — from concrete concerns about immigration, about job insecurity and poverty, and about haves and have-nots to less tangible feelings of displacement and disconnect, of unease in changing times and of dissatisfaction with our political institutions.

Concerns such as these resonate above all in poorer communities, particularly the former industrial heartlands that have largely missed out on the benefits of economic modernisation and globalisation — in other words, Labour-voting communities. Here was Labour’s Brexit conundrum: an instinctively Remain party whose traditional base largely voted to leave. It is one that the party leadership singularly failed to solve.

The question of Brexit quickly became the unilateral nuclear disarmament issue of our times, exposing a key fault line in the party’s cross-class coalition of support. Like unilateralism in the 1980s, opposition to Brexit was a policy espoused passionately and instinctively by Labour’s middle-class membership — young, university-educated, city-based, cosmopolitan in outlook and lifestyle — but largely alien to its traditional working-class base.

But Brexit alone cannot explain Labour’s catastrophic election …

Click here to read more thoughts about British politics and failures of leadership.