Books, TV and Films, July 2020

1 July

Some thoughts, to begin with, on Philomena and On Chesil Beach, two films I watched last week on the BBC and thoroughly enjoyed.

I was already aware of Martin Sixsmith, who wrote the book on which Philomena is based, from his time as a foreign correspondent at the BBC in the ’90s; it’s probably why I also vaguely remember his involvement in a bust-up with the Blair government a few years later. In Philomena the part of Sixsmith is played by Steve Coogan. He (Sixsmith) is not a particularly sympathetic character in my eyes: he is reluctant to take on the investigation at first (having been approached by Philomena Lee’s daughter to write about her mother who, as a young unmarried mother, was forced to give up her son by the Catholic Church in Ireland) and comes across as somewhat self-absorbed. His portrayal in the film carries the same sense of an exaggerated version of reality that is the central conceit of The Trip, the series in which Coogan stars with Rob Brydon.

The character of Philomena, played by Judi Dench, is satisfyingly multilayered. Initial impressions of her as merely eccentric, unworldly and frankly not very bright are quickly dispelled. She is quick to realise — and, despite her faith, to accept — that her son was gay and died of Aids. And despite the despicable way in which she had been (and, in the film version at least, continued to be) treated by the Catholic Church, she also comes across as dignified and remarkably forgiving. Sixsmith, on the other hand, is reduced to outbursts of impotent rage. Forgiveness is a central teaching of Christianity; but how many Christians would be able to find it in their hearts to be as forgiving as Philomena, I wonder.

I watched this just a few weeks after watching Spotlight, also based on a true story, about the work of a special investigations unit attached to the Boston Globe to expose the systematic cover-up by the Catholic Church, over a period of decades, of sexual abuse of children by priests. Both are powerful, disturbing and moving films, laying bare how innocent lives have been blighted by powerful institutional forces. And then I watched On Chesil Beach, which features malign influences of a different kind.

I read Ian McEwan’s novella a couple of years ago. I was particularly keen to watch the film adaptation because (a) McEwan himself wrote the screenplay and (b) it features Saoirse Ronan, a huge talent among the current generation of young actors.

It is set in 1962 but it might just as easily have been 1963, the year that sexual intercourse began, at least for Philip Larkin. Though the title references a place, I see this more as a story about a time — Britain after postwar austerity but before the so-called Swinging Sixties, when supposedly we never had it so good (yes, I am being a little unfair to Harold Macmillan with that misquote) — and about the dominant attitudes and mores of the era, not least with regard to sex.

This tale is a searing indictment of how we thought and behaved and preached and moralised and condemned, not really all that long ago: people’s lives — in this case Florence and Edward, but how many in reality, heterosexual as well as homosexual? — constrained, deformed and ultimately ruined by society’s prudish, repressive and in many cases hypocritical attitudes to sex.

Though much of the background story is told in flashback, the main setting for the film is the honeymoon suite of the couple’s hotel. The sniggering pageboys providing room service convey the immature, schoolboy-ish mentality that the Carry On series later so successfully lampooned. The couple are both virgins but their first night (well, afternoon) together is not a blissful consummation of their love; it is an ordeal to be overcome.

Edward is a fumbling, bumbling wreck, unable even to take off his pants. Florence has been reduced to taking tea with the local vicar and reading cold, mechanical sex manuals (think John Cleese classroom sketch in The Meaning of Life) to try and learn about sexual intercourse. She is clearly traumatised at the prospect of having sex. The film doesn’t make clear exactly why, but McEwan leaves us enough clues to suggest that it is as a result of childhood abuse from her father.

I interpreted the wild and unspoiled terrain of Chesil Beach itself as standing in stark contrast to the way in which the natural instincts of Florence and Edward have been repressed, controlled and restricted.

Great stuff from McEwan, as always. I seem to remember the ending of the book is different. It’s definitely on my shortlist to reread.

10 July

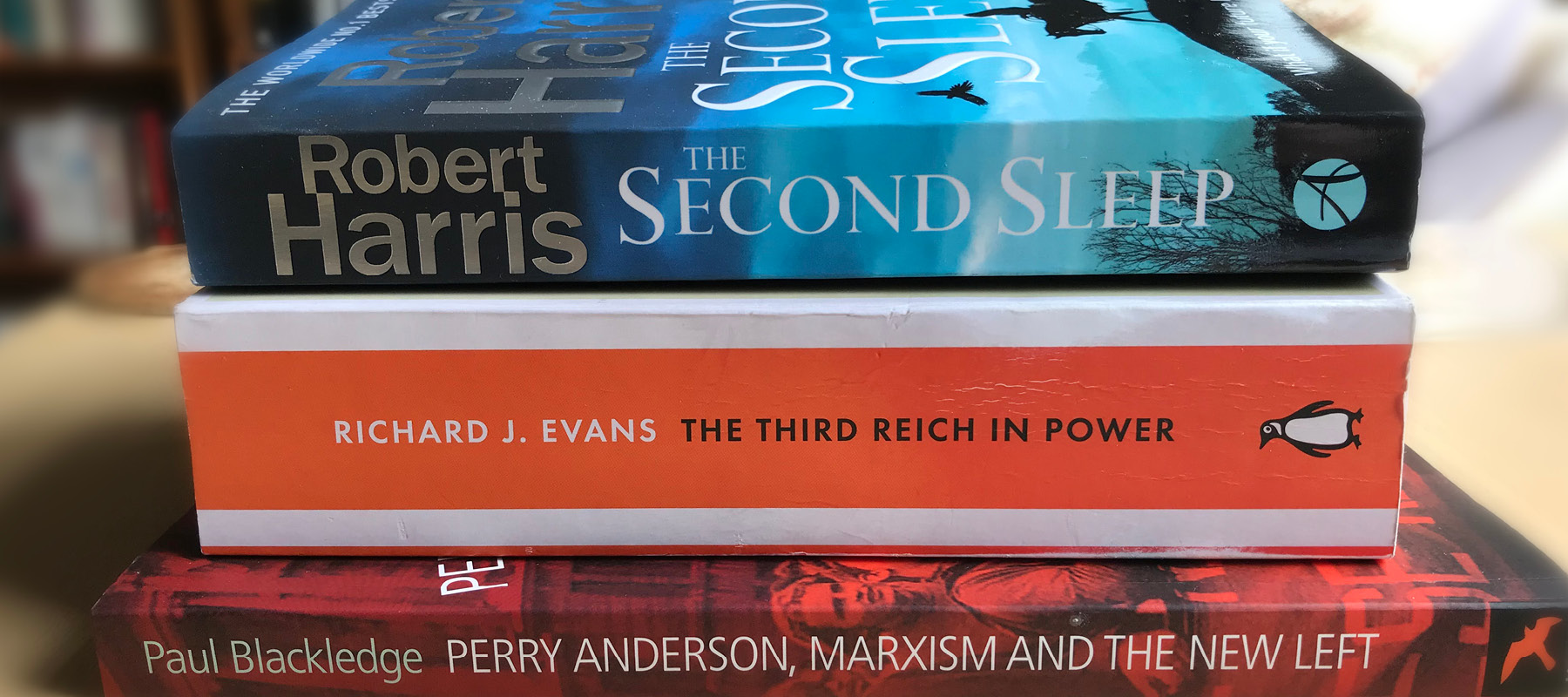

Richard J Evans’ The Third Reich in Power is turning into a mammoth undertaking. It’s a big book anyway (712 pages, not counting the extensive end-notes) and I have a lot of work on at the moment. I was hoping to read 50 pages a day but most days I’m only managing about 40.

I say this often but, in these benighted times when experts are widely distrusted and the meaning of words like ‘truth’ and ‘fact’ are seemingly up for grabs, it needs saying over and over again: what a joy it is to read a book like this, written by an acknowledged expert on the subject. There are the broad judgements he makes, of course: I particularly enjoyed the ‘revolutionary or reactionary’ discussion that ends the book. Sometimes, though, it’s little details and anecdotes. This one, in particular, caught my attention: on the morning after the Nazi-Soviet Pact had been announced the front garden of Nazi Party headquarters was covered in party badges thrown there by disgruntled party members.

One thing about this book that really stands out is the way it is organised. It is divided into seven parts, each with four chapters and each of roughly similar length. This is clearly an artificial contrivance and yet it all fits together so beautifully. At no point does it really feel as if content has been placed in a certain section merely to fit the framework, though inevitably there is a lot of potential overlap between Mobilisation of the Spirit (propaganda, arts and culture) and Converting the Soul (religion, school, universities, the Hitler Youth).

19 July

A huge birthday treat — the latest Robert Harris novel, The Second Sleep, is just out in paperback. I have been waiting for this for ages. I think publication of the paperback edition may have been delayed because of the coronavirus emergency. I really like Harris anyway, but when I first read the synopsis I was genuinely excited because it covered favourite ground — time travel or, to be absolutely precise, playing around with history.

On Twitter someone asked what kind of stuff Harris writes. It took me a while to think of what to reply because, though all his books are rooted in history and/or politics, it ranges from ‘alternate reality’ (Fatherland) to novels that stick fairly close to actual events (An Officer and a Spy; Munich). I eventually answered: ‘Mainly well-plotted thrillers, often tied in with real historical events. Superbly researched.’

24 July

I finished the last 100 pages of The Second Sleep this morning. It certainly lived up to my expectations, ranging across several of my favourite fictional genres — mystery; thriller; history-twister (is that a genre?). It is brilliantly structured and genuinely gripping; we’re talking Robert Harris, after all.

I will need to go back and re-read the final 50 pages or so, I think. There are twists and turns aplenty, as you would expect with any good novel of this type. I was turning the pages so quickly by the end that there is much I doubtless missed. Nothing was quite as it seemed. I also found it to be refreshingly thought-provoking. Others have commented that it is an urgently needed ‘wake-up call’; it’s certainly hard to miss the many references to plastic.

As someone long interested in the science and reason versus faith and religion debate — and associating myself very clearly with one side of the argument — I found that the book added some welcome hues to my monochromatic thinking, illustrating the value and strengths as well as the dangers and weaknesses of both sides.

28 July

I repeatedly find myself drawn back to the world of left-wing politics and political ideas — specifically the heyday of the so-called New Left in the ’60s and ’70s and its precipitous decline in the ’80s. I am re-reading Perry Anderson, Marxism and the New Left by Paul Blackledge, which I first read three or four years ago probably.

I find this milieu endlessly fascinating. It’s the discussion of ideas that draws me in, encompassing political theory, philosophy, history, sociology and economics. No doubt it’s partly the challenge. Left-wing thinkers, in particular, seem to delight in abstruse theorisation. An appropriate level of abstraction, they might say; gobbledegook, others would doubtless counter. The conservative philosopher Roger Scruton excoriates them mercilessly in his brilliant Fools, Frauds and Firebrands. Sometimes you really do have to wonder if Scruton has a point:

John Roberts has criticised [them] for what he argues is a systematic confusion in their work between “the end of the avant-garde as the positivisation of the revolutionary transformation in action … and the avant-garde as the continuing labour of negation on the category of art and the representations and institutions of capitalist culture.”

from end-note 73 of Perry Anderson, Marxism and the New Left

Putting this sort of tripe to one side, I find that, as I widen and deepen my reading, I am understanding more each time, especially as my very sketchy grasp of philosophy improves. Perry Anderson himself is a fascinating figure. Astonishingly well read, he was a leading left intellectual by his mid-20s, taking over the editorship of New Left Review at an extraordinarily young age and using it as a vehicle to introduce new left-wing thinking from continental Europe.

The history of the New Left, especially in the ’60s, is as much about generational divides and personality clashes as it is about theoretical arguments. Two interconnected threads of the story are of particular interest. The first is the debate, with Anderson at its centre, over why Britain never developed an indigenous Marxism, a debate that focused in part on rival interpretations of key moments of British history, especially the English Civil War. The second is the attempt, particularly associated with the historian EP Thompson, with whom Anderson repeatedly clashed, to articulate a socialist humanism in contradistinction to the mechanical, ‘scientific’ Marxism that was in vogue particularly in the ’70s.