Rush: A Fan’s Appreciation

Note — 11 January 2020

I heard the awful news late last evening that Neil had died earlier in the week of — of all things — brain cancer. What a cruel roll of the bones for such a cerebral and erudite human being. This appreciation was originally written in June 2018 after years of hoping against hope that Rush would work again and possibly even play in Europe. Neil was 67 years of age. Far too fleet, indeed.

Suddenly you were gone / From all the lives you left your mark upon

Afterimage. Lyrics by Neil Peart.

It looks increasingly like that’s finally and, at least semi-officially, it: Canadian rock legends Rush are no longer a going concern, it seems. Anecdotes about various age-related physical ailments and wanting to spend more time with the family have been circulating for some time but, for this fan, the absence of European dates on the back of the ‘R40’ American tour said it all. It’s impossible in a few paragraphs to do more than scratch the surface of the Rush phenomenon, of course, but — for what it’s worth — here are a few random reflections on (cliché-alert) Canada’s premier power trio.

First of all, ‘rock legends’ – really?! After all, it’s a reasonable bet that more than a few music fans, young and not so young, would probably struggle to identify anything much by Rush beyond those staples of rock CD ‘Best Of…’ collections, The Spirit of Radio and Tom Sawyer. Not for nothing have Rush been characterised as ‘the biggest cult band in the world’. Yet the statistics – gazillions of album sales over 40 years, supported by countless sold-out tours – are undeniable. Deeply unfashionable, maybe, but in a long and distinguished career they have repeatedly reinvented themselves and their music since those early Page-inspired riffs and lyrical nods to Tolkien.

I discovered Rush around 1977, eleven years old and just encountering the giants of what was then being disparaged and dismissed as ‘dinosaur rock’ – the likes of Genesis, Yes and Pink Floyd. The band’s prog-rock era, with its elaborate pieces, grandiose sweep and multi-layered depths, culminating in the two ‘Cygnus’ albums, represents for me their creative peak. Epics such as 2112, Xanadu and La Villa Strangiato are a timeless joy, 40-plus years after their release.

In the wake of punk, a stripped-down, simplified, back-to-basics aesthetic revolutionised rock music. In 1978 Yes released an album made up of nine – yes, nine! – songs; Led Zeppelin jettisoned the extended solos on their 1980 European tour, almost halving the duration of their live show; and if there was an overarching theme to Genesis’s 1981 album, it was neatly encapsulated by the stark a-b-a-c-a-b structure of an early version of one of the tracks they recorded during the sessions. Meanwhile, a ‘new wave of British heavy metal’ – the likes of Iron Maiden, Def Leppard and Whitesnake – surfaced in Britain and made it big in America: commercial, catchy, radio-friendly.

Rush, too, moved with the times. The Spirit of Radio’s opening riff heralded a decade of musical invention and experimentation. Prog-rock epics were replaced by shorter, streamlined, more ‘accessible’ songs. Geddy’s increasing use of keyboards, at times battling the dominance of Alex’s guitars in the mix, coupled with Neil’s embrace of electronic drums, modernised their sound. The early 80s – Permanent Waves, Moving Pictures and Signals – represent the band’s most commercially successful period, their moment in the sun.

For some, this new sound was too mellow, anodyne, adulterated. Actually I love those albums but, anyway, the appeal of Rush was always about more than just the music. Fiercely proud of their musical proficiency, Rush were also clever, thoughtful and cultured. Take their tour programmes, album artwork and prodigious sleeve notes, packed with witty, sometimes arcane, references – Brought to you by the letter ‘M’ – or the exhaustive inventories, meticulously cataloguing the band’s equipment, seemingly down to the last bass pedal, guitar pick and cymbal. Speaking of the tour programme, how exhilarating to read Neil’s word-perfect mini-essays, tracing the gestation of the current album, its musical forms and lyrical themes.

My least favourite albums are probably those from the 90s. Pick up anything from Presto to Test for Echo and expect a collection of maybe ten five-minute songs, including a title track and an instrumental. In a word: formulaic. Yet the ‘90s also produced a sprinkling of undoubted career highs, not least Bravado, Neil Peart’s hymn to heroic failure. Rush were not alone in negotiating creative peaks and troughs but I remain baffled by Planet Rock magazine’s ‘Buyer’s Guide’, which recently [Issue 2: July 2017] featured nothing after 1985’s Power Windows in their Rush top ten. How many groups can boast of releasing two outstanding albums in the autumn of their career – Snakes and Arrows and Clockwork Angels – worthy of comparison with their very best work?

I came late to the first three albums (repackaged as a collection called Archives after the success of 2112). It’s a story of a band finding its feet and the tale of 2112 as a make-or-break album is well known. I rarely play the first album, despite the classics Working Man and Finding My Way. Perhaps it’s my nod to Neil Peart; his absence makes Rush (the album) feel more like proto-Rush. I delved deeper into Fly by Night (Peart’s first album) after rediscovering All the World’s a Stage, particularly the hidden gem In the End and the album’s tour de force By-Tor and the Snow Dog. It’s so typical of the band’s ambition and early experimentation, the savage fight for dominion perfectly realised through the snarling interplay of bass and guitar, rival champions of Hell and the Overworld.

Most intriguing, for me at least, is the somewhat maligned Caress of Steel. I Think I’m Going Bald may be a rare misfire but Bastille Day was a raucous live opener in its day (inexplicably nudged out by Lakeside Park on the R40 tour). The Fountain of Lamneth, originally taking up the whole of side two, is a consistently overlooked bundle of interesting, if semi-formed, ideas. Like digging through The March of the Black Queen on Queen II to unearth the roots of Bohemian Rhapsody, this bold 20-minute musical experiment, with its discrete sections, frequent mood changes and baffling time signatures, foreshadows their coming masterpiece, 2112.

I only saw Rush in concert in the latter years; ‘R30’ was my first tour. [Long after publishing this appreciation, I remembered that I actually first saw them on the Hold Your Fire tour, at Birmingham in April 1988, some of which was used on the A Show of Hands live album.] Their live show is exceptionally well documented on film and CD. Has any other group released quite so much live material during their ‘active’ years, I wonder? The musicianship was always exemplary, the visuals compelling and the band’s humour, often self-deprecating, at its most conspicuous. But with only three people, the complexity and multi-instrumentation of the music made it difficult to faithfully reproduce the Rush sound live. Technology to the rescue: but therein lies a quandary. How much of the ‘live’ Mystic Rhythms, to take a random example, was actually being played live? One consequence of this reliance on technology was too few opportunities to experiment on stage. Only on the very final tours did the band seem to take steps to rectify this, creating space in the set to, well, fiddle around a bit.

Then there are the words.

How grating it is to hear someone lazily pigeon-hole Rush’s lyrics as ‘fantasy/Dungeons & Dragons’. Just as the band repeatedly reinterpreted and reinvented their sound, so Peart’s writing ranged across numerous forms and themes, his words always crafted with style, wit and intelligence. Take Losing It from Signals, Peart’s meditation on the effects of ageing on the creative process, its wistful sentiments perfectly complemented by the plaintive echoes of the electric violin. Or Closer to the Heart: What better commitment from loving adult to child than “You can be the captain and I will draw the chart”? Or Afterimage: What more fitting summation of the devastating impact of unexpected loss than “Suddenly you were gone / from all the lives you left your mark upon”?

The lyrical themes of the Snakes and Arrows album from 2007 cover similar ground to the book God Is Not Great by Christopher Hitchens (also 2007) and Richard Dawkins’ The God Delusion (published a year earlier). Peart was wrestling with these issues much earlier, of course. Free Will (1980), for example, rejects the notion of supernatural determinism: “A host of holy horrors to direct our aimless dance”. Mystic Rhythms (1985) is a paean to what Dawkins himself later called ‘the magic of reality’.

In its time (1976) the lyrics of 2112 – “Inspired by the genius of Ayn Rand” – earned the band a certain notoriety after elements of the British music press condemned its anti-totalitarian message as proto-fascism. While Ayn Rand’s philosophy is certainly associated with the extreme neo-liberals of the postwar years, I rather think that the criticism says more about the political and cultural myopia of the left in the 1970s. With the collapse of communism, who now seriously doubts that totalitarianism in all its forms, whether of the left or of the right, stifles freedom and creativity?

So many themes, so many wonderful lines. Perhaps then it is fitting that the final song on the final album is The Garden – Peart’s nod to Voltaire’s novel Candide – in which the narrator talks (metaphorically) of “a garden to nurture and respect”. For this fan at least, Rush leave us a wonderful legacy of forty years of music worthy of nurture and respect.

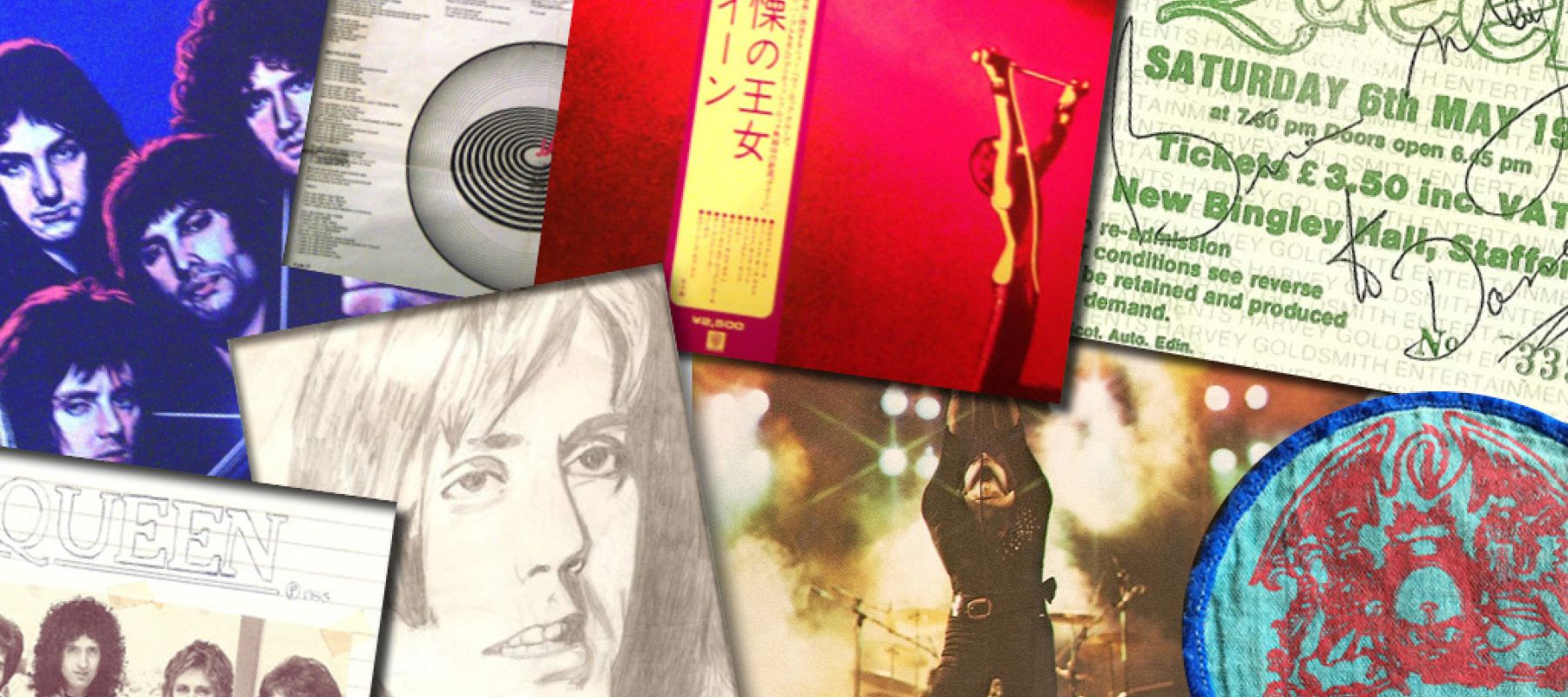

So glad I saw this and read your tribute to the one and only “Rush”. Like you I entered the fray with “Kings” (a la Britannia Music Club offering of the time), the album was being pushed by the Club at the time and the cover looked interesting to a 12 year old who also liked to read books. I never missed any of their albums as they were released but was disenchanted with Signals (my first live show, Wembley 1983) which blew me away! I can still recall the numerous times NP threw hiss ticks up in the air precariously and Alex sporting his New wave haircut jacket and tie,

Geddy keeping the faith with his long locks. I was lucky enough to indoctrinate my 2 kids both of whom saw Rush live and my son and I used my redundancy money to see them for the last time on R40+ in NYC, first time I saw them with the double necks coming out of the Xanadu mist, my eyes filled up as they did on numerous occasions over the last few months at the loss of Neil.

Thanks very much for taking the time to write something. I really appreciate it and I am delighted you enjoyed what I wrote.

My brother, who is older than me, got into them first via 2112 and saw them on the Permanent Waves tour. I didn’t get to see them until the R30 tour (Edit: I tell a lie — I saw them in Birmingham on the Hold Your Fire tour. Crikey, I had completely forgotten!). For both of us, those prog-rock albums — 2112, Kings, Hemispheres — are peak Rush.

Britannia Music Club. Blimey, that’s a name I haven’t heard in a while. What was it, six albums for a ridiculously cheap price but then you had to buy from them regularly at full price? I can’t remember.