Aneurin Bevan Biography Review

Bevan was a passionate man, a man of unimpeachable integrity and honesty, a great orator (indeed, one of the towering parliamentary speakers of the century) and an able minister and administrator — a true political heavyweight. Yet, we sense also an imperious temperament, a restless and ambitious spirit, prone to bouts of petulance and arrogance, and demanding unquestioning loyalty from his devoted followers.

Diogenes

Nye Bevan by John Campbell

Arguably, Aneurin Bevan, the miner-turned-politician who became in roughly equal measure the darling of the British labour movement and the bête noire of the right-wing establishment, is better remembered than any other member of the historic 1945–51 Labour government — better than his colleagues Ernie Bevin (part-architect of Nato), Stafford ‘Austerity’ Cripps and even the prime minister himself, Clem Attlee. This is because Bevan’s name will be forever linked in the public consciousness with the NHS, which, as minister of health, he brought into being in 1948.

Unlike every other political issue of that era — it pre-dates serious squabbles over Europe by more than a decade and outlasted the Cold War— the health service continues to excite debate and controversy today. In this splendid biography, John Campbell examines the pertinent issues: the extent to which the NHS was Bevan’s own creation; his dealings with interested parties such as the BMA; the administrative and financial structures put in place to support this audacious social experiment; and the post-1948 political fallout.

Tellingly, however, Campbell devotes a mere 30 or so pages directly to the NHS — though indirectly it casts a lengthy shadow across the latter half of the book and the final decade of his life — because there was, in fact, so much more to this remarkable figure, a combustible mix of self-taught intellectual, instinctive rebel, eager, ambitious minister and charismatic leader. Campbell provides us with a fully rounded portrait of the man as well as analysing his impact on the Labour Party. He tackles with impeccable balance the highs and lows of Bevan’s life: the (relatively few) periods of triumph as well as the more frequent times of struggle, failure and schism — not to mention odd moments of bathos, most notably the publication of an eagerly anticipated book In Place of Fear in 1952.

Bevan was a passionate man, a man of unimpeachable integrity and honesty, a great orator (indeed, one of the towering parliamentary speakers of the century) and an able minister and administrator — a true political heavyweight. Yet, we sense also an imperious temperament, a restless and ambitious spirit, prone to bouts of petulance and arrogance, and demanding unquestioning loyalty from his devoted followers. Moreover, it becomes apparent that his judgements about politics, about future developments, about the nature of mankind no less, were often seriously flawed, a consequence of a deterministic Marxism that he learnt in his youth and carried almost to the grave.

The controversies surrounding Bevan did not end with his untimely death in 1960. The party wounds of the 1950s, patched up for the 1959 hustings, were reopened well before the election of Wilson’s unhappy government in 1964. Thus, the first volume of Michael Foot’s biography, published in 1962, brilliantly written to be sure, is hagiographic and tendentious and reads best, as Campbell himself says, as “an episode in the long-running civil war” within the party.

Foot, himself a born rebel and Bevan’s acolyte-in-chief, refused to serve in Wilson’s first government and then renewed the fight with a second volume in 1973. In an excellent introduction, Campbell deals with Bevan’s political legacy, particularly the claim made for Bevan’s imprimatur by a host of Labour politicians (the latest, to update Campbell, being John Reid, Blair’s health secretary since 2003) as they re-brand and re-invent policies — or (increasingly) consign them to the dustbin — and seek to sell a new manifesto to a deeply sceptical and conservative movement.

John Campbell is a fine, experienced biographer, scrupulously fair in the judgements that he reaches. The book is authoritatively written and meticulously researched, marred only by a handful of proofing errors. I confess to finding one ‘Wildean’ slip (a reference to Alan Bullock’s book Earnest Bevin [sic] in the bibliography) highly amusing but, as a reader with no knowledge of the publishing world, I am puzzled as to why such errors should remain to blight later editions of published works. This book was originally published under the title Nye Bevan and the Mirage of British Socialism in 1987 and re-issued with an abridged title ten years later, presumably to mark the coincidence of the centenary of Bevan’s birth and Blair’s first landslide.

Reading Campbell opens a window on the politics of a bygone era, allowing us to draw comparisons with modern times. Take age, for example. With Tony Blair having been prime minister for seven years by the time he reached 50, it is fascinating to learn that Bevan himself was the most junior member of the 1945 Cabinet aged 47. Or, take the press. Setting the headlines Bevan received c1951 alongside the obituary notices of a decade later, reminds one of the kicking meted out to Tony Benn, Bevan’s successor as Labour’s bogey man in the 1970s and 1980s — now rather fondly admired as a harmless, slightly eccentric, elder statesman.

The writer uses a 1997 introduction to update us on important political developments in the decade since the first edition; the main text, however, seems to be untouched and, as Campbell went to some trouble to relate the political controversies in Bevan’s life to the issues of the 1980s (particularly Neil Kinnock’s battles to modernise party policy vis-à-vis nationalisation and unilateralism), the reader is left with an unmistakeable sense of the ephemerality and sheer unpredictability of modern politics. For example, writing in 1987, Campbell was obviously taking seriously predictions of the Labour Party’s terminal electoral decline (p253 — “Some would say [the 1951 election defeat] was the beginning of the end of the Labour Party”); a mere 14 years later in 2001 it was the Conservatives about whom such prognostications were being uttered.

I thoroughly recommended this marvellous book to political animals and the intelligent general reader alike.

This review relates to the edition published in 1997. It was uploaded to Amazon in 2004.

Rush: A Fan’s Appreciation

Note — 11 January 2020

I heard the awful news late last evening that Neil had died earlier in the week of — of all things — brain cancer. What a cruel roll of the bones for such a cerebral and erudite human being. This appreciation was originally written in June 2018 after years of hoping against hope that Rush would work again and possibly even play in Europe. Neil was 67 years of age. Far too fleet, indeed.

Suddenly you were gone / From all the lives you left your mark upon

Afterimage. Lyrics by Neil Peart.

It looks increasingly like that’s finally and, at least semi-officially, it: Canadian rock legends Rush are no longer a going concern, it seems. Anecdotes about various age-related physical ailments and wanting to spend more time with the family have been circulating for some time but, for this fan, the absence of European dates on the back of the ‘R40’ American tour said it all. It’s impossible in a few paragraphs to do more than scratch the surface of the Rush phenomenon, of course, but — for what it’s worth — here are a few random reflections on (cliché-alert) Canada’s premier power trio.

First of all, ‘rock legends’ – really?! After all, it’s a reasonable bet that more than a few music fans, young and not so young, would probably struggle to identify anything much by Rush beyond those staples of rock CD ‘Best Of…’ collections, The Spirit of Radio and Tom Sawyer. Not for nothing have Rush been characterised as ‘the biggest cult band in the world’. Yet the statistics – gazillions of album sales over 40 years, supported by countless sold-out tours – are undeniable. Deeply unfashionable, maybe, but in a long and distinguished career they have repeatedly reinvented themselves and their music since those early Page-inspired riffs and lyrical nods to Tolkien.

I discovered Rush around 1977, eleven years old and just encountering the giants of what was then being disparaged and dismissed as ‘dinosaur rock’ – the likes of Genesis, Yes and Pink Floyd. The band’s prog-rock era, with its elaborate pieces, grandiose sweep and multi-layered depths, culminating in the two ‘Cygnus’ albums, represents for me their creative peak. Epics such as 2112, Xanadu and La Villa Strangiato are a timeless joy, 40-plus years after their release.

In the wake of punk, a stripped-down, simplified, back-to-basics aesthetic revolutionised rock music. In 1978 Yes released an album made up of nine – yes, nine! – songs; Led Zeppelin jettisoned the extended solos on their 1980 European tour, almost halving the duration of their live show; and if there was an overarching theme to Genesis’s 1981 album, it was neatly encapsulated by the stark a-b-a-c-a-b structure of an early version of one of the tracks they recorded during the sessions. Meanwhile, a ‘new wave of British heavy metal’ – the likes of Iron Maiden, Def Leppard and Whitesnake – surfaced in Britain and made it big in America: commercial, catchy, radio-friendly.

Rush, too, moved with the times. The Spirit of Radio’s opening riff heralded a decade of musical invention and experimentation. Prog-rock epics were replaced by shorter, streamlined, more ‘accessible’ songs. Geddy’s increasing use of keyboards, at times battling the dominance of Alex’s guitars in the mix, coupled with Neil’s embrace of electronic drums, modernised their sound. The early 80s – Permanent Waves, Moving Pictures and Signals – represent the band’s most commercially successful period, their moment in the sun.

For some, this new sound was too mellow, anodyne, adulterated. Actually I love those albums but, anyway, the appeal of Rush was always about more than just the music. Fiercely proud of their musical proficiency, Rush were also clever, thoughtful and cultured. Take their tour programmes, album artwork and prodigious sleeve notes, packed with witty, sometimes arcane, references – Brought to you by the letter ‘M’ – or the exhaustive inventories, meticulously cataloguing the band’s equipment, seemingly down to the last bass pedal, guitar pick and cymbal. Speaking of the tour programme, how exhilarating to read Neil’s word-perfect mini-essays, tracing the gestation of the current album, its musical forms and lyrical themes.

My least favourite albums are probably those from the 90s. Pick up anything from Presto to Test for Echo and expect a collection of maybe ten five-minute songs, including a title track and an instrumental. In a word: formulaic. Yet the ‘90s also produced a sprinkling of undoubted career highs, not least Bravado, Neil Peart’s hymn to heroic failure. Rush were not alone in negotiating creative peaks and troughs but I remain baffled by Planet Rock magazine’s ‘Buyer’s Guide’, which recently [Issue 2: July 2017] featured nothing after 1985’s Power Windows in their Rush top ten. How many groups can boast of releasing two outstanding albums in the autumn of their career – Snakes and Arrows and Clockwork Angels – worthy of comparison with their very best work?

I came late to the first three albums (repackaged as a collection called Archives after the success of 2112). It’s a story of a band finding its feet and the tale of 2112 as a make-or-break album is well known. I rarely play the first album, despite the classics Working Man and Finding My Way. Perhaps it’s my nod to Neil Peart; his absence makes Rush (the album) feel more like proto-Rush. I delved deeper into Fly by Night (Peart’s first album) after rediscovering All the World’s a Stage, particularly the hidden gem In the End and the album’s tour de force By-Tor and the Snow Dog. It’s so typical of the band’s ambition and early experimentation, the savage fight for dominion perfectly realised through the snarling interplay of bass and guitar, rival champions of Hell and the Overworld.

Most intriguing, for me at least, is the somewhat maligned Caress of Steel. I Think I’m Going Bald may be a rare misfire but Bastille Day was a raucous live opener in its day (inexplicably nudged out by Lakeside Park on the R40 tour). The Fountain of Lamneth, originally taking up the whole of side two, is a consistently overlooked bundle of interesting, if semi-formed, ideas. Like digging through The March of the Black Queen on Queen II to unearth the roots of Bohemian Rhapsody, this bold 20-minute musical experiment, with its discrete sections, frequent mood changes and baffling time signatures, foreshadows their coming masterpiece, 2112.

I only saw Rush in concert in the latter years; ‘R30’ was my first tour. [Long after publishing this appreciation, I remembered that I actually first saw them on the Hold Your Fire tour, at Birmingham in April 1988, some of which was used on the A Show of Hands live album.] Their live show is exceptionally well documented on film and CD. Has any other group released quite so much live material during their ‘active’ years, I wonder? The musicianship was always exemplary, the visuals compelling and the band’s humour, often self-deprecating, at its most conspicuous. But with only three people, the complexity and multi-instrumentation of the music made it difficult to faithfully reproduce the Rush sound live. Technology to the rescue: but therein lies a quandary. How much of the ‘live’ Mystic Rhythms, to take a random example, was actually being played live? One consequence of this reliance on technology was too few opportunities to experiment on stage. Only on the very final tours did the band seem to take steps to rectify this, creating space in the set to, well, fiddle around a bit.

Then there are the words.

How grating it is to hear someone lazily pigeon-hole Rush’s lyrics as ‘fantasy/Dungeons & Dragons’. Just as the band repeatedly reinterpreted and reinvented their sound, so Peart’s writing ranged across numerous forms and themes, his words always crafted with style, wit and intelligence. Take Losing It from Signals, Peart’s meditation on the effects of ageing on the creative process, its wistful sentiments perfectly complemented by the plaintive echoes of the electric violin. Or Closer to the Heart: What better commitment from loving adult to child than “You can be the captain and I will draw the chart”? Or Afterimage: What more fitting summation of the devastating impact of unexpected loss than “Suddenly you were gone / from all the lives you left your mark upon”?

The lyrical themes of the Snakes and Arrows album from 2007 cover similar ground to the book God Is Not Great by Christopher Hitchens (also 2007) and Richard Dawkins’ The God Delusion (published a year earlier). Peart was wrestling with these issues much earlier, of course. Free Will (1980), for example, rejects the notion of supernatural determinism: “A host of holy horrors to direct our aimless dance”. Mystic Rhythms (1985) is a paean to what Dawkins himself later called ‘the magic of reality’.

In its time (1976) the lyrics of 2112 – “Inspired by the genius of Ayn Rand” – earned the band a certain notoriety after elements of the British music press condemned its anti-totalitarian message as proto-fascism. While Ayn Rand’s philosophy is certainly associated with the extreme neo-liberals of the postwar years, I rather think that the criticism says more about the political and cultural myopia of the left in the 1970s. With the collapse of communism, who now seriously doubts that totalitarianism in all its forms, whether of the left or of the right, stifles freedom and creativity?

So many themes, so many wonderful lines. Perhaps then it is fitting that the final song on the final album is The Garden – Peart’s nod to Voltaire’s novel Candide – in which the narrator talks (metaphorically) of “a garden to nurture and respect”. For this fan at least, Rush leave us a wonderful legacy of forty years of music worthy of nurture and respect.

Bill Clinton Autobiography Review

A thematic approach might have allowed a more coherent analysis of Clinton’s overall record in office. On the other hand, the book at least has the advantage of raising issues as Clinton experienced them at the time (with occasional — and brief — pauses for reflection); day-to-day events are not neatly compartmentalised. One is frequently astonished by the bewildering pace of modern public life as Clinton lurches from one critical issue to the next.

Diogenes

My Life by Bill Clinton

Jed Bartlet, the fictional US president in TV’s The West Wing, is a political hero of mine, so it’s perhaps not surprising that I find myself instinctively warming to Bill Clinton. The Bartlet character is, in part, a reflection of Clinton — a deeply religious, hard working, liberal internationalist, driven by the desire to serve community and country.

A self-styled ‘New Democrat’, Clinton first came to national prominence as governor of Arkansas in the 1980s. Architect of the once-fashionable ‘Third Way’, Clinton modernised the progressive message by co-opting core ideas from the conservative agenda (fiscal hawkishness, family values, work not welfare) and infusing them with a strong belief in social justice and opportunity for all. Along the way, he revitalised a factious Democratic Party, forced the Republicans to the wilderness of the radical right and blazed a trail for his soulmate Tony Blair to follow in Britain after 1994.

I approached this autobiography with some trepidation — as well as a dictionary of American idioms and an atlas. Though a keen student of politics, I am a novice with regard to American government; its systems, structures and procedures seem arcane and baffling. Another potential obstacle for the British reader is the vernacular of American politics, a problem compounded by the folksy, conversational style of Clinton’s writing. Hence, I’m still not au fait with the politics of campaign finance reform, ‘soft money’ and the rest and Clinton’s confession that, during preparations for the 1996 presidential TV debates, George Mitchell “cleaned my clock” just mystified me.

Aside from the Bartlet parallels, it is evident that the Clinton presidency has proved a rich seam of storylines and subplots for The West Wing, as well as helping this reader negotiate his way through the White House labyrinth. Thus, I was suitably prepared for the bizarre tradition of pardoning a turkey each Thanksgiving; meanwhile, issues as diverse as brinkmanship in the Taiwan Straits, America’s refusal to sign an anti-landmines treaty and backstairs haggling with congressional movers and shakers all have a familiar feel.

My Life is really two books spliced together – the one more enjoyable than the other. The weaker ‘Book 2’ covers the years of Clinton’s presidency. Written as a breathless narrative, this diary of events is a whistle-stop tour of domestic and (especially) international politics — a handy primer, perhaps, for first-year politics undergraduates — with everything from trade relations with South America to climate change negotiations meriting a paragraph or so.

A thematic approach might have allowed a more coherent analysis of Clinton’s overall record in office. On the other hand, the book at least has the advantage of raising issues as Clinton experienced them at the time (with occasional — and brief — pauses for reflection); day-to-day events are not neatly compartmentalised. One is frequently astonished by the bewildering pace of modern public life as Clinton lurches from one critical issue to the next. Even opportunities for mourning — whether for family (his mother), close friends and colleagues (Vince Foster) or political leaders (Yitzhak Rabin) — are sharply curtailed in the maelstrom of activity, and Clinton himself questions the extent to which he was truly master of ceremonies.

Less welcome is the overwhelming sense that everyone, but everyone, merits a line; My Life reads in places like a roll-call of thanks, of debts acknowledged and repaid. Yet, we are told that the final draft omitted “countless” numbers of people along the way. Central to Clinton’s survival and success in the cut-throat world of American politics was his remarkable ability, from a young age, to stockpile friendships (the so-called FOB — ‘Friends of Bill’) and build up networks of powerful acquaintances across the social spectrum who could be mobilised when required to campaign tirelessly on his behalf.

This is a major thread running through ‘Book 1’ — the years before 1993. At times, the young Clinton comes across as almost too earnest: the reader comes to expect each paragraph to end with a lesson gleaned from each experience or happenstance of life. Nevertheless, it’s an appealing story of an intelligent and thoughtful young man raised in a poverty-stricken southern state struggling to come to terms with trends in postwar society, through university (including two years at Oxford) under the shadow of Vietnam and ultimately to a career in politics.

Some readers will buy this book to read about the scandals that bedevilled his time in office. It is, of course, Clinton’s opportunity to present his own version of events but there is enough soul-searching and self-criticism throughout the book to convince me of his basic integrity, humanity and overwhelming commitment to public service. If his version of the ‘Whitewater’ story is one-sided then it is arguably a welcome corrective after incessant mudslinging by a largely hostile and partisan media, happy to accept financial backing from implacable opponents of Clinton and to weigh in with presumptions of guilt. Revealingly, Clinton refers to ‘Whitewater World’. He is implying, in effect, that the obsessives who lived the story year-on-year were ‘on another planet’ but it also suggests a psychological need to ‘box off’ Whitewater in his own mind in order to get on with the day-to-day job of governing.

The absence of prurient detail is welcome but his sexual shenanigans did have a major impact on his life story: they put his marriage under intense strain, almost cost him the Democratic nomination in 1992 and led to an impeachment trial. Yet, the first reference to his adultery only comes during his account of the Gennifer Flowers furore at the time of the New Hampshire primary in early-1992. Politicians are, of course, entitled to a private life that is private but this politician has written his autobiography — My life not My Political Life — and one is left in this case with a nagging sense of a lack of full disclosure.

This review relates to the hardback edition, published in 2004. It was uploaded to Amazon in August 2004. Other than stylistic updates, the only alteration to the text is the addition of several paragraph breaks and of the word ‘nagging’ in the final sentence.

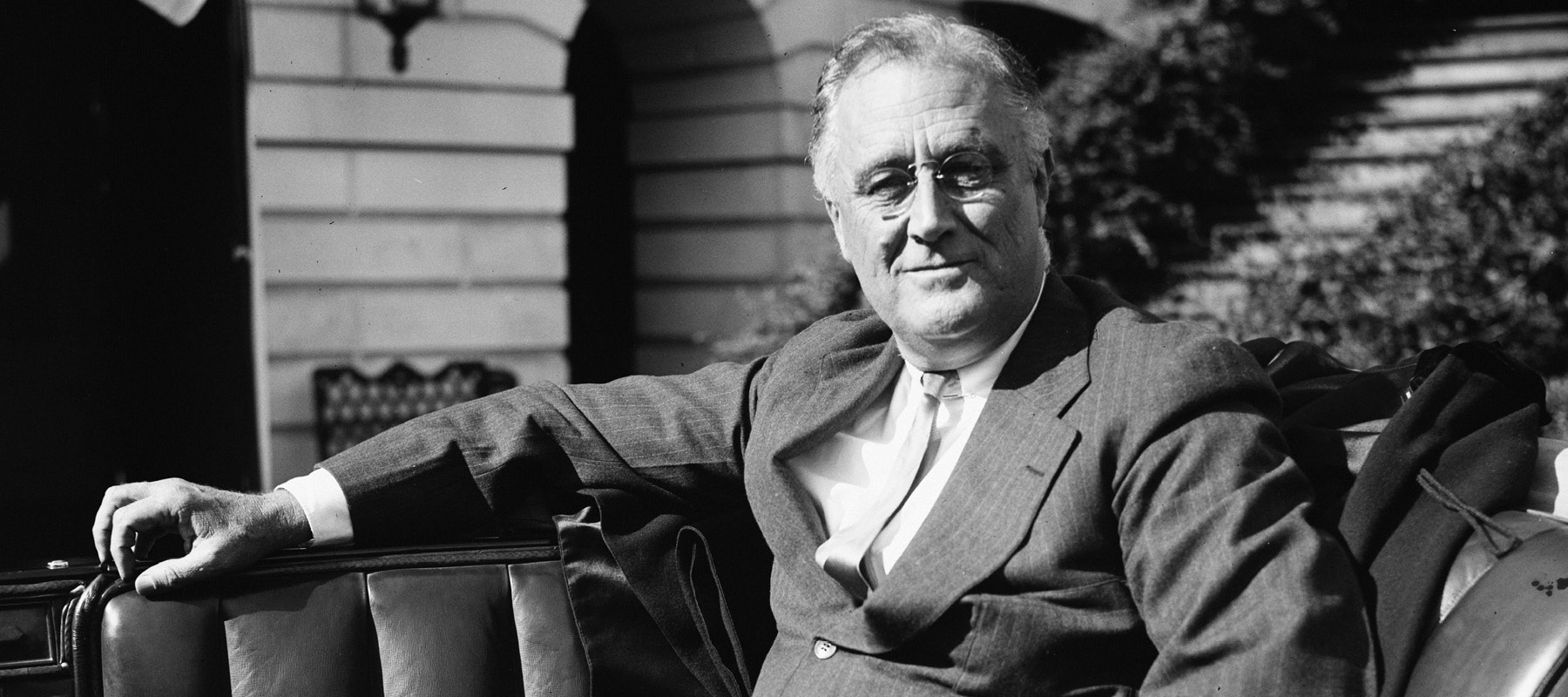

‘Franklin Delano Roosevelt’ Review

One is left with a nagging sense of disappointment that the Grand Old Man of the British centre didn’t bequeath to us the definitive story of this liberal internationalist and champion of progressive politics — a man very much like Jenkins himself, in fact.

Diogenes

Franklin Delano Roosevelt by Roy Jenkins

A ‘Note on the Text’ declares that Roy Jenkins died “[s]hortly before completing the final text of this book”. We are further told that the text was completed by Professor Richard Neustadt to whom Jenkins was intending to show his manuscript. Perhaps Jenkins then planned to flesh out the book; for, in truth, this slight work has much more the feel of a draft rather than the finished product.

Its focus continued Jenkins’ penchant for tackling the ‘greats’ of modern political history; FDR is certainly in the top rank of American presidents. This book probably arose out of the writing of his excellent Churchill, as the stories of these “two great superstars” so obviously converged in the years 1940 to 1945; there are also many parallels as well as points of contact in their lives — as Jenkins is quick to draw out.

However, the myriad references to Churchill (and to a lesser extent Gladstone) eventually become irksome and increasingly feel like fillers — evidence, in fact, of an unpolished, unfinished work. Frankly, after Gladstone and Churchill, 720 pages and 1024 pages respectively, this book seems altogether too slight for a political giant such as FDR.

Of course, there is nothing intrinsically inferior about the slim biographical volume (see Norman Stone’s Hitler, for example) but, if this really was Jenkins’ intention, then the reader is left questioning the overall shape and balance of the book. To cite one example from page 99, Jenkins devotes a lengthy paragraph to details of the international context of the later-1930s. And yet, major events in FDR’s career worthy of in-depth exploration — his time in the federal government before and during the First World War and his governorship of New York between 1928 and 1932, to cite two glaring examples — are all but passed over or sketched out in cursory detail. Elsewhere, storylines are left dangling in the air; his wife Eleanor, for example, a key figure in the early part of the book, virtually disappears from the story after 1933.

For the intelligent general reader (ie non-specialist), relevant factual information is often lacking (what, for example, was the “very messy naval drugs and homosexual scandal” of 1919–20?); meanwhile, the student of American history is left bemoaning the absence of definitive, closely argued Jenkinsonian judgements on the New Deal and Allied Grand Strategy during the Second World War.

A further tell-tale sign of a ‘work in progress’ is Jenkins’ observation on page 21 that “the politics of party loyalty from time to time makes monkeys of all who accept it”. Quite possibly true — and Jenkins would know as well as most — but this reader was rather disappointed when Jenkins reuses exactly the same idiom on page 113. Further, for a biographer with such an ability to select the telling phrase or the revealing anecdote, it seems curious that that he should feel the need (page 123) to spell out the punchline to the “savage joke” of Britain’s military superiority in 1940–41. This reader also found the Americanised text — “behavior”, “harbor” and so on — an annoyance.

And yet, as always, there is much to admire in Jenkins’ style — the felicitous phrase, vivid imagery (“mahogany-voiced”) and idiosyncratic choice of vocabulary (“eleemosynary”, which means ‘charitable’) — though, at times, even Jenkins perhaps overreaches slightly (the medal table image on page 4 and the extended dancing metaphor on page 126–27 spring to mind). The confidence with which he draws comparisons between historical personalities is a joy; we can revel in his assessment of the best US presidents, the most effective vice-presidents and the British prime ministers who outstayed their welcome.

His pen-portraits of people (one senses that Jenkins actually knew them: indeed, on occasion, he did) and places are deliciously well drawn; he effortlessly sketches the privileged milieu of America’s New York-based patrician class into which FDR was born. In so doing, he demonstrates that the skilled biographer is at least as well placed to portray an historical time and place as the writer of a general history. The trademark wit and an eye for quirky detail are still evident; his observation that, when staying at FDR’s family home, King George VI would probably have had to traverse the bedroom of the Canadian PM (also a guest) for a midnight pee is quintessential Jenkins.

This book can be recommended in the general sense that anything written by Roy Jenkins is worth reading. But in truth it is something of an anticlimax, an unsatisfactory swansong after two magna opera. It is questionable whether Jenkins has even nailed the case for FDR’s greatness. One is left with a nagging sense of disappointment that the Grand Old Man of the British centre didn’t bequeath to us the definitive story of this liberal internationalist and champion of progressive politics — a man very much like Jenkins himself, in fact.

This review relates to the hardback edition, published by Macmillan in 2004. It was uploaded to Amazon in June 2017. Minor amendments have been made to the original text.

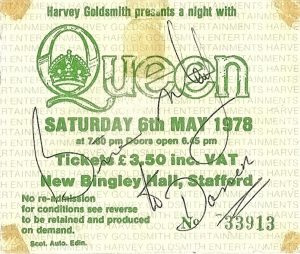

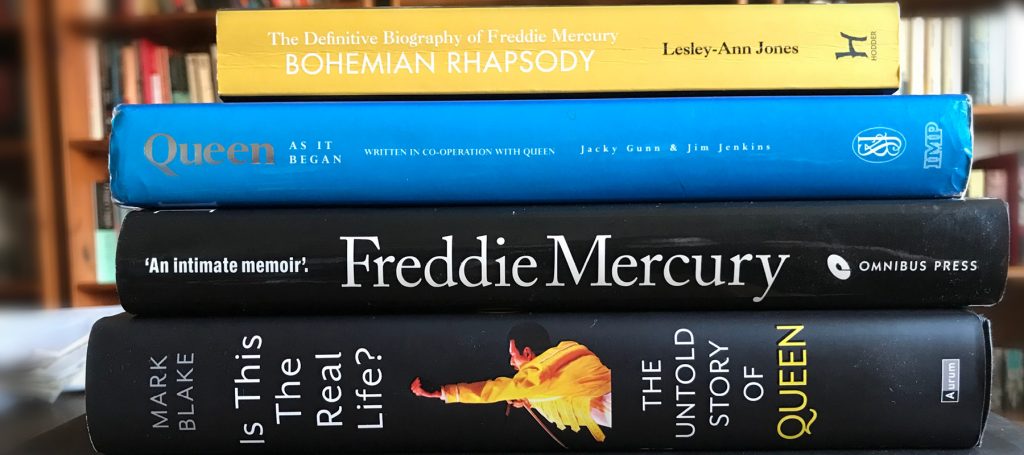

‘Queen in 3–D’ Review

The viewer can almost feel the heat generated by the ‘pizza oven’ lighting rig (page 135) or reach out to touch the various drums and cymbals that surround Roger on stage (page 151, for example).

Diogenes

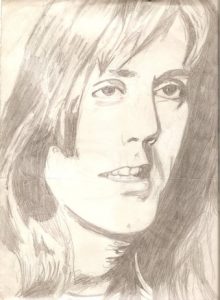

Queen in 3–D by Brian May

Brian May is an extraordinary individual. Best known as one of the members of the legendary group Queen and widely acknowledged to be one of the most innovative guitarists in the history of rock music, he is also an accomplished astrophysicist with a PhD in interplanetary dust and a tireless campaigner on behalf of the cause of animal welfare. May is also an aficionado of Victorian photography, his interest in which is closed linked to a lifelong passion for the world of 3-D photographs — stereoscopy.

The result is this magnificent book: lavishly packaged, beautifully presented and full of hundreds of previously unseen photographs — many but not all in 3-D — spanning the entirety of Queen’s career up to the final tour with Freddie Mercury in 1986 and beyond to Brian and Roger’s collaborations with Paul Rodgers and Adam Lambert. The extraordinary influence on Brian of his parents — particularly his father, Harold, with whom he famously built his ‘Red Special’ guitar — is also evident through the inclusion of intimate family photographs, including Brian’s first efforts to take 3-D photographs in the back garden as a child and pictures of proud mum and dad visiting Brian on tour in the USA in 1977.

For the reader interested in learning the basics of stereoscopy, there is a full but accessible explanation at the beginning of the book of the principles and techniques of 3-D photography and, throughout, references to the different makes and models of camera used to take various photographs. The real joy of the book, however, is to be found in the photographs themselves — many taken spontaneously — capturing the band and its entourage on and off stage, at work and at play. For the Queen obsessive (like me), there is treasure to be found on every page.

Despite the limitations of camera technology, every phase of the band’s career is covered, thanks in part to May’s (increasing) willingness to lend his camera(s) to others to capture pictures of the band, particularly on stage. The result is that ‘the early years’ are documented visually as never before — from shots of the band in rehearsal above a long-forgotten pub before the release of the first album to moments of relaxation during the recording of A Night at the Opera. Coverage of their tours of Japan is particularly extensive, perhaps because Brian was trying out new technology available over there long before it hit western shops.

Though the older photographs inevitably lack a certain sharpness, the graininess actually serves to enhance their authenticity, irresistibly drawing the viewer into the scene. This book demonstrates that, at its most effective, 3-D photography offers a far more intimate and ‘realistic’ representation of a moment than conventional ‘flat’ photographs. Consider, for example, the feelings of claustrophobia induced in the viewer by the back-of-the-limousine photograph of the band on page 36 and the image of Freddie, Mary and John huddled in an aeroplane crossing the American continent on page 103. The viewer can almost feel the heat generated by the ‘pizza oven’ lighting rig (page 135) or reach out to touch the various drums and cymbals that surround Roger on stage (page 151, for example).

There is a substantial accompanying text (and captions), placing the individual photographs in their historical and geographical context. More than that, the text reads almost as a mini history of the band, sketchy in places but nevertheless packed with insights and anecdotes, many previously unheard, at least by this reader. As May says in his introduction, the text is entirely his own, unmediated by a co-author or ghost writer. His ‘voice’ is instantly recognisable to visitors to ‘Brian’s Soapbox’ on his website and, for the most part, this works absolutely fine. Only occasionally do detours up and down the byways and ‘B’ roads of May’s many passions threaten to distract us on this wonderfully nostalgic journey — recurring references to animal rights, in particular. Less agreeable are references to up-to-the-minute (2017) political issues — particularly Trump and Brexit — the inclusion of which will inevitably date those segments of the text.

Having paid £50 for the book, inevitably I find that the few errors and typos grate — not least, the thank-you dedication to Roger on page 4 (“benificence” … unless that’s an in-joke). There are also references to “Jeff Lynn” and “Max von Sidow”. The involvement of Queen archivist Greg Brooks ensures that the factual history is extremely accurate, though the caption on page 134 that the robot face on Roger’s bass drum was never used in Europe is simply wrong, as many photographs can attest.

This reader did feel that the picture of the stage set-up at Madison Square Garden on page 167 was somewhat misleading. Its appearance beneath a chapter-heading stating ‘1980’ with a caption urging the reader to compare it with a picture taken in February 1977 implies a three-year gap between the two photographs, when in fact the page 167 picture is clearly from the News of the World tour in November 1977 (the magnificent ‘Crown’ lighting rig is clearly visible) – a gap of only a few months.

One puzzle is May’s reference to Led Zeppelin’s dramatic lighting effects on stage; he refers to witnessing a powerful performance of Kashmir in Wisconsin. Kashmir is on the Physical Graffiti album, released in 1975, but May dates the performance to “just before we were a proper touring entity”. Either his memory is faulty on this point or he is suggesting that Queen only really ‘got their act together’ with the live show from the A Night at the Opera tour later in 1975.

Nonetheless, these minor quibbles — hopefully, corrected or clarified in a future edition — pale into insignificance when set against the many, many delights to be found in this five-star book.

More about Queen

This review was first uploaded to Amazon in May 2017.

Who was Diogenes?

The flimsier the historical evidence, the more entertaining the characters and stories.

Diogenes (me, not the philosopher)

The above is not a ‘law’ of history as such, but it is a useful rule of thumb nonetheless. The philosopher Diogenes left us nothing in writing. Instead, into the evidential vacuum rushes a combination of myths, tall tales and caricature — not so much what EP Thompson called the enormous condescension of posterity, more our insatiable desire for a good story. Hence the modern-day popularity of tabloid newspapers, celebrity gossip and online ‘clickbait’ stories. Who cares if the reality is altogether more down to earth?

And there is certainly no shortage of good stories connected with Diogenes: the man who lived in a tub; the man who walked round in daylight with a lamp ‘looking for a man’; the man who was lippy to Alexander the Great and lived to tell the tale; the man who masturbated, urinated and defecated in public.

In fact, other than a few scraps of information, little is known for certain about Diogenes. He was born in the late fifth century BC in Sinope, a bustling seaport on the Black Sea. As a young man, he was caught up in some sort of scandal, possibly involving his father and the local currency, forcing him to leave his home and possessions behind. One story has him consulting the oracle at Delphi and receiving advice to ‘deface the currency’ – at face value, a typically enigmatic oracular pronouncement, given that currency defacement may have been at the heart of the earlier scandal.

But, if we interpret ‘currency’ to refer to conventional standards and codes of behaviour, then the instruction becomes one of cocking a snook at polite society, of deliberately upsetting the applecart. If so, this puts him somewhere near the head of a long line of contrarians and non-conformists through history – the sort of people AJP Taylor, in a different context, referred to affectionately as ‘troublemakers’.

The story of Diogenes reminds us of the old truism about taking time to dig deeper rather than rushing to judgement. Diogenes and his master Antisthenes are regarded as the original Cynics, founders of the Cynic school of philosophy. Cynicism, an unappealing and unpleasant attribute, well described by HG Wells as “humour in ill health” is defined by the OED as “[b]elieving that people are motivated purely by self-interest; distrustful of human sincerity or integrity” and “[c]oncerned only with one’s own interests and typically disregarding accepted standards in order to achieve them.” But the name ‘cynic’ actually derives from the Greek for ‘dog-like’ and was a reference to the extreme squalor in which Diogenes and others chose to live.

His inspiration was Socrates, who rejected the link between material comforts and happiness, as well as fiercely championing open-mindedness and the right to question authority. It became the basis of his method of teaching (‘Socratic dialogue’) and a supreme virtue in itself. Stories of the lifestyle Diogenes chose – dressing in rags, begging, eschewing the comforts of conventional life – sound remarkably similar to the extreme asceticism practised by religious adherents down the ages.

Rejection of crude materialism and of conventional standards and norms of living was their route to freedom – freedom, that is, from human failings such as pride, desire and jealousy. Diogenes’ follower, Crates, supposedly abandoned a rich inheritance to embrace the life of the Cynic. Only with the actions of later followers of Diogenes and the first Cynics – shamelessly living off the largesse of others, relentlessly satirical and sarcastic – did ‘cynicism’ acquire the characteristics we now associate with the word.

As for his more extreme utterances, given that none of his writings survive (if indeed he even wrote anything) who can possibly say whether words and views attributed to him – incest and cannibalism, anyone? – were actually said and, even if they were, whether they were meant literally or just for shock value, another way of upsetting conventional tastes.

In reality, the antecedents of many of the values and principles that liberal democracy rightly cherishes – freedom of conscience, universal brotherhood, respect for all life, including that of animals – can be found in the teachings of Socrates and the Cynics who followed. Far from being cynical in its modern usage, they were passionately interested in moral virtue: the representation of Diogenes as the ‘man with a lamp’ actually links to his supposed search for a truly ‘just’ man.

And so we come to the fictional Diogenes Club, first mentioned in Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes. Containing “the most unsociable and unclubable [sic] men in town”, its members were expected to ignore each other and talking was not permitted under any circumstances. Eccentric, peculiar, unconventional – the name ‘Diogenes’ seems fitting. But Diogenes matters for another reason, too. The word ‘cosmopolitan’ – citizen of the world – possibly originated with him. In these days of growing intolerance, rampant bigotry and narrow-minded xenophobia, at levels not witnessed since the 1930s, this minor fact, apart from anything else, seems to me to recommend him as a figure of interest.