Books, TV and Films, April 2020

6 April

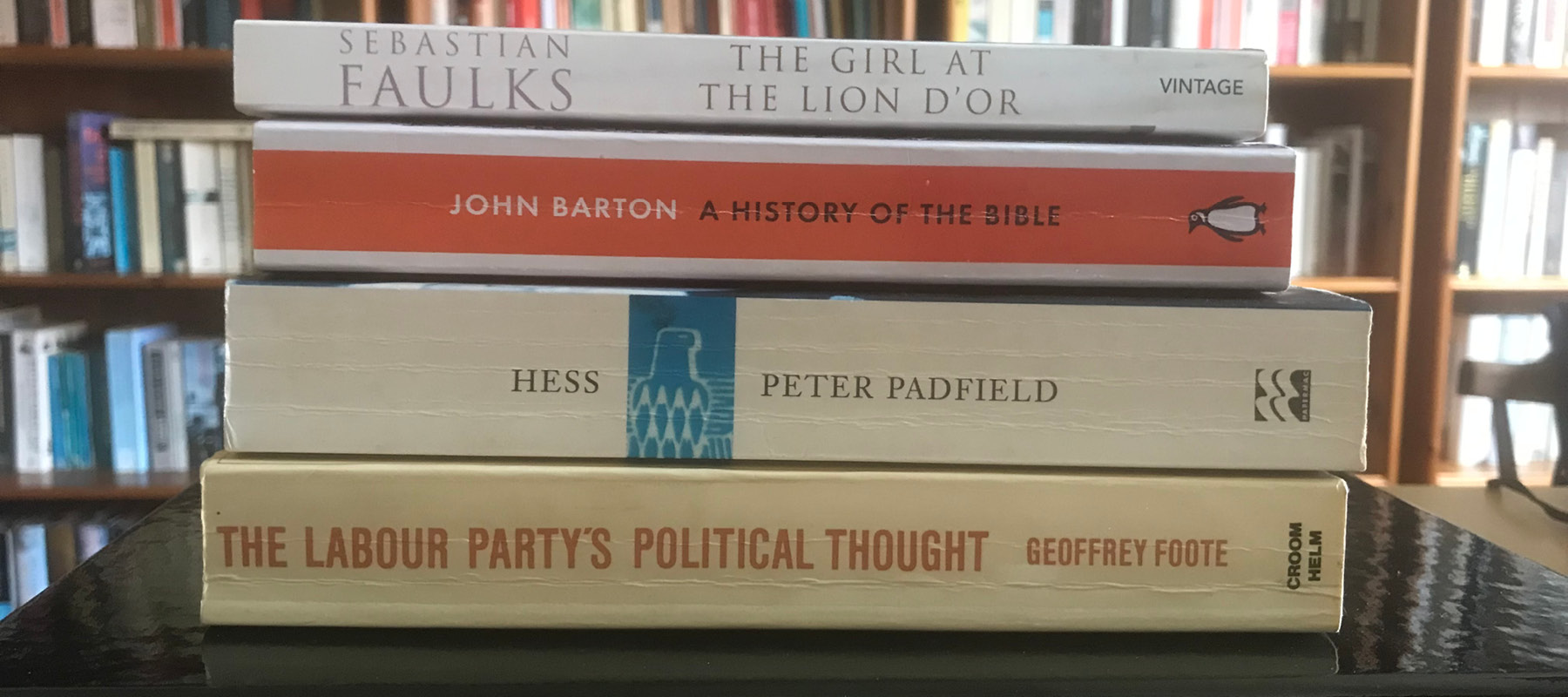

John Barton’s A History of the Bible: The Book and Its faith is proving an absolute treat. My interest in religion and belief systems has developed over the last decade or so, triggered — does this count as irony? — by reading Richard Dawkins. Anyway, last year I read the huge but hugely enjoyable A History of Christianity by Diarmaid MacCulloch. Professor Barton is another distinguished Oxford academic.

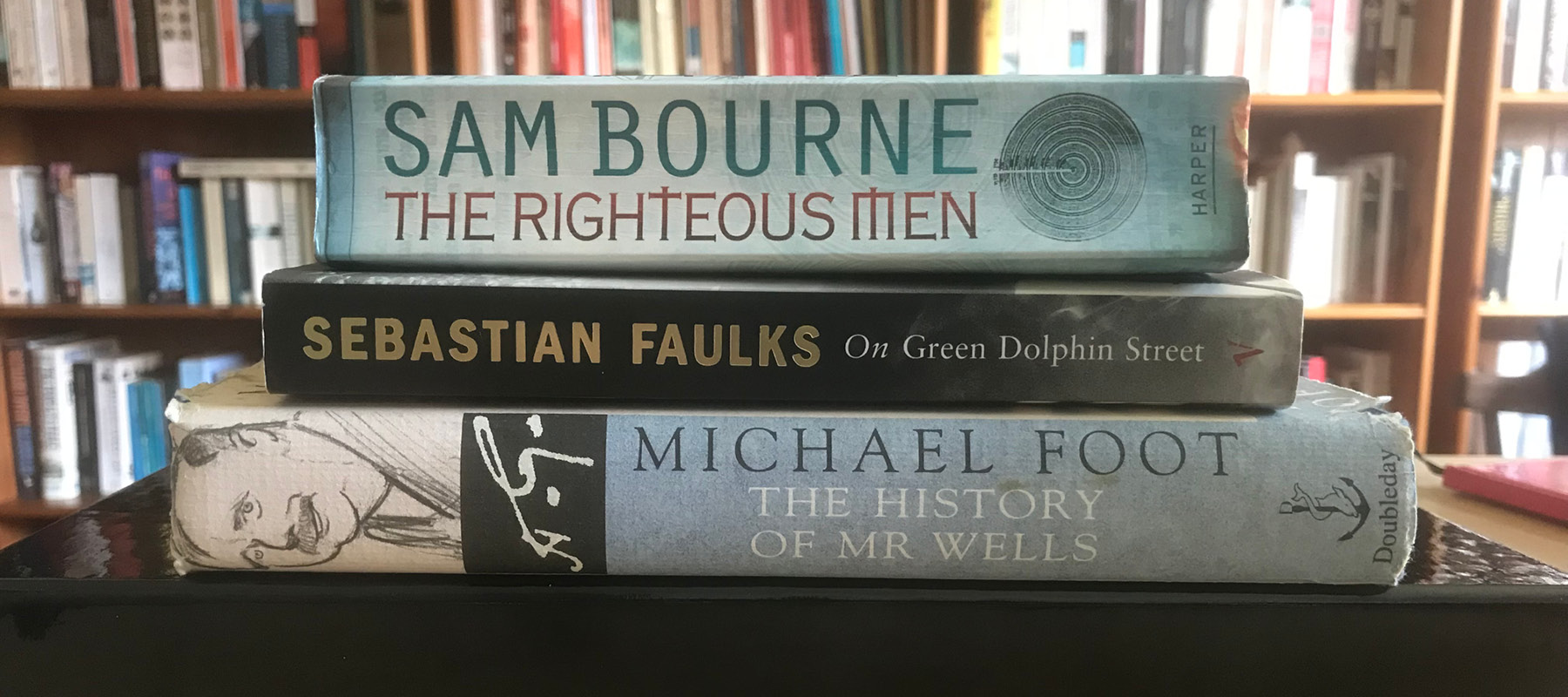

First of all, it was a pleasure to read — not just well written but also accessible. The contrast with the Michael Foot biography of HG Wells is telling. The Foot book required a great deal of background knowledge to make sense of it; Barton, on the other hand, goes out of his way to make his text accessible to the general reader.

Apart from its readability, this book is exactly what I look for when reading about something I don’t really know much about. Key words and concepts are clearly explained, even basics such as the meaning of ‘testament’, as in Old Testament. Important facts, ideas and arguments are covered succinctly, and revisited and reinforced.

Controversies and areas of disagreement (of which there are many) are set out before the reader. Barton does not shy away from telling us what he thinks, which I like. I turn the page confident that his conclusions and judgements are judiciously reached, and that I am being led along a tricky and complicated path by an expert guide.

9 April

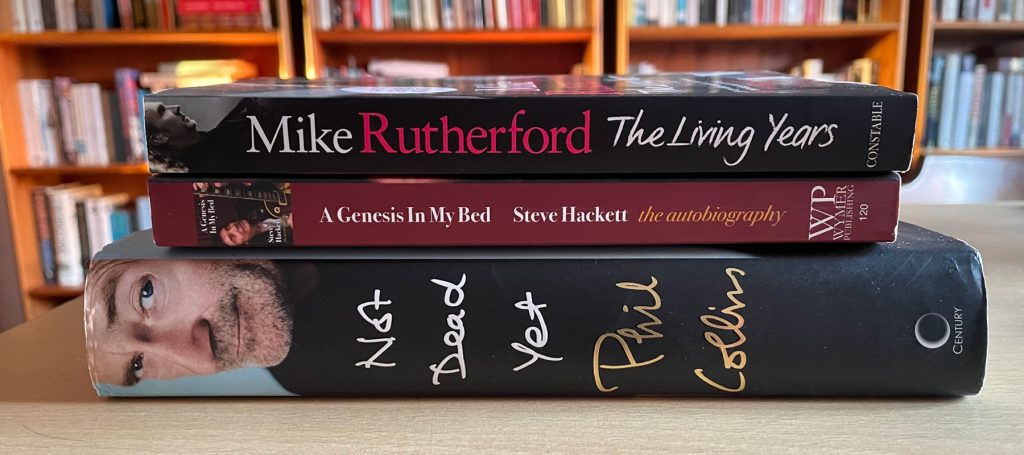

Having planned in December to write something about the general election and the future of the Labour Party, I find that I have now written two blogposts about politics and still not really addressed what Labour ought to do next. Having read Mark Bevir’s book in January on the early years of British socialism and the ideas that were influential at the time when the Labour Party was founded, I have decided to re-read The Labour Party’s Political Thought: A History by Geoffrey Foote.

I bought the book at university, probably in 1986. I remember laughing about the front cover, which features photos of three men — Ernie Bevin, Tom Mann and Neil Kinnock. The photo of Kinnock, who was a new-ish Labour leader when the book was published, is twice the size of the other two, even though Kinnock only features in the final few pages.

I suppose there is an argument that it emphasises the connection between history and politics, but I can’t help thinking that’s it’s really a sales ploy by publishers to give history books an of-the-moment appeal.

13 April

It’s the Easter bank holiday weekend. Having just read John Barton’s history of the Bible, I am certainly noticing the many media references to biblical events, chiefly (of course) the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus. It’s striking how often these events are written about as if they were established historical facts.

In the absence of live sport on TV, I am working through a backlog of unwatched films and dramas. I have just re-watched Elizabeth with Cate Blanchett as the eponymous queen, Dickie Attenborough as a well-intentioned but deeply conservative William Cecil, Christopher Eccleston stuck on fast-forward as a sinister Duke of Norfolk and a brilliant Geoffrey Rush as Francis Walsingham. I have just started watching Mary Queen of Scots, which stars the wonderful Saiarse Ronan (definitely had to look up that spelling) and I have the Elizabeth follow-up, Elizabeth: The Golden Age, still to come.

I mentioned Mary Queen of Scots and The Favourite (which I have also just watched) in a blogpost called Fake History and Film. It is quite astonishing the liberties taken with the historical record in all of these films. Elizabeth, in particular, seems to have cut up a chronology of historical events into individual pieces and randomly reassembled them — either that or just made things up (assuming that she wasn’t really in a long-term sexual relationship with Dudley). Quite astonishing.

A leading article in today’s Guardian talks of revisiting ideas from Labour’s past, mentioning ethical socialism, William Morris and RH Tawney. Just what I have been doing!

18 April

Just finished the Foote book on the Labour Party’s political thought. Two immediate thoughts.

Books on politics age very quickly. That’s why I don’t often buy them. This is mainly a history of political ideas, but the concluding chapter (written in 1985) deals with then-current political thinking. It has not aged well. Events and developments are all viewed through a Marxist lens, and so his critical analysis just seems woefully out of date from the perspective of 2020.

Like many on the hard left, the author can’t quite bring himself to believe that the majority of the British people don’t subscribe to his idea of socialism: “[o]nly by risking a short-term unpopularity through industrial action could the long-term reward of electoral office be obtained,” he writes, in the context of union militancy at around the time of the miners’ strike of 1984. Yuk.

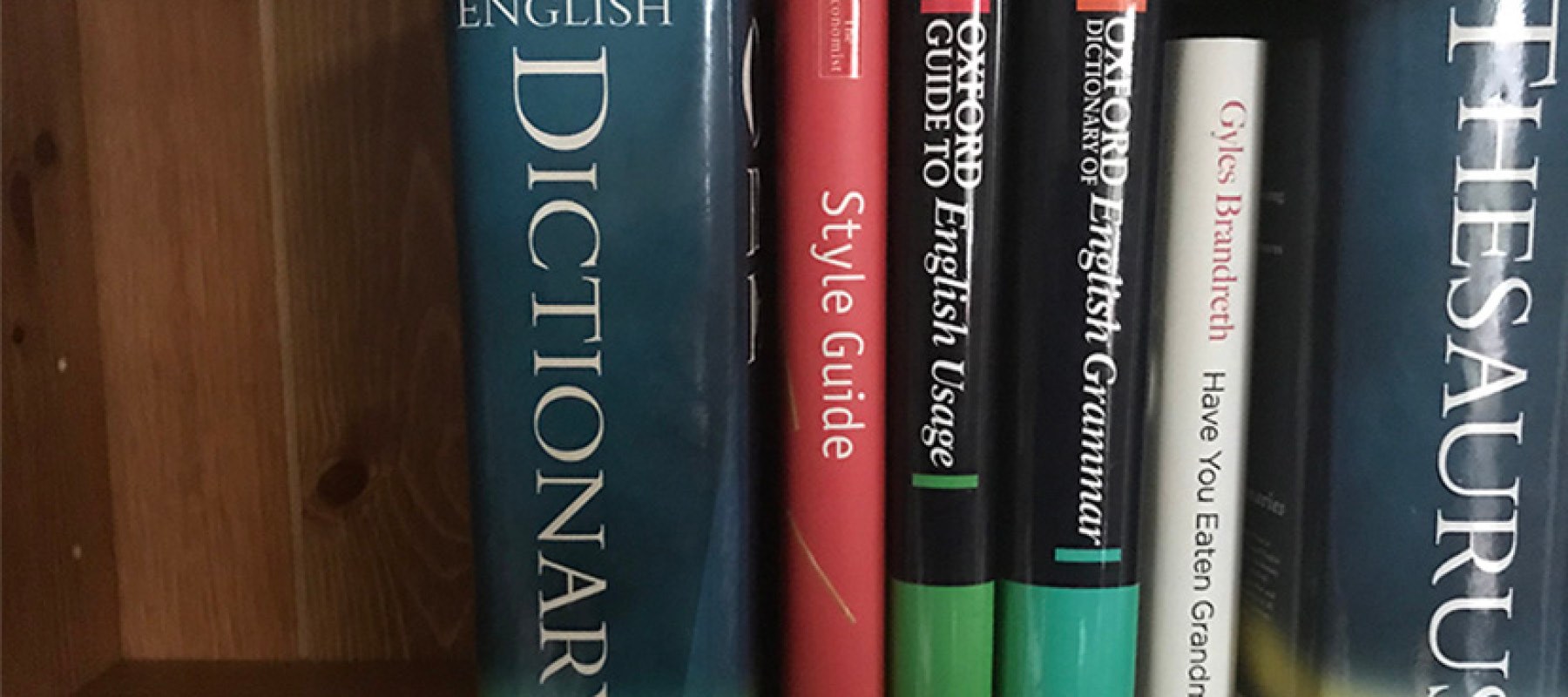

The second thing to note — something that would have completely passed me by until a few years ago — is the poor quality of the proofreading and copy-editing. To be fair, it’s presumably a fact of life for many small, cash-strapped publishers. There are a number of noticeable typsetting errors. More annoyingly, there seems to be absolutely no consistency with regard to capital letters. Style guides vary, but at least be consistent!

Sentences like this one are not uncommon:

The Social Contract … was finally destroyed by the discontent of the union rank and file in the winter of discontent in 1978-9.

Out-and-out spelling mistakes — as opposed to typographical errors — are (as far as I am aware) relatively unusual in books. They get the benefit of the doubt with ‘legitimatist’ — it should probably be ‘legitimist’ — but I was astonished to see Bevan’s famous quote about Gaitskell written as “a dessicated [sic] calculating machine”.

22 April

I finished binge-watching War of the Worlds last night — the 2020 Anglo-French production shown on the Fox cable channel: eight episodes (each of about 45 minutes’ duration) over three days. Set in the present, it’s nothing like the book, I don’t think, except for the basic fact that it’s about an alien invasion. It was bleak and properly dystopian. I was enjoying the slow unfurling of the story and the time taken on character development until I realised by about episode 6 that it wasn’t unfurling anything like quickly enough to reach a conclusion. Sure enough, the final episode sets us up for a second series. How disappointing.

Time for another Sebastian Faulks novel — The Girl at the Lion d’Or. It was published in 1989, so is very early (his first, possibly). I read it ages ago but, to be honest, I can remember hardly anything about it. The character names vaguely ring a bell, as do some seemingly incidental details. I note that a reviewer quoted on the back cover recommends it to fans of The French Lieutenant’s Woman, another novel that I read a very long time ago (possibly in the mid-’80s) and can remember very little about.

27 April

I finished The Girl at the Lion d’Or yesterday. It’s only 250 pages and didn’t take long; I had no trouble reading more than my 10% minimum daily target.

It’s the first of three Faulks novels set in France in the first half of the twentieth century — this one takes place in the ’30s, the final decade of the Third Republic. Just like On Green Dolphin Street, which I read last month, the novel is beautifully crafted: it’s a love story, but so much more as well. Every character, every event (however seemingly incidental), every exchange, every detail helps paint a picture of France in the years leading up to its collapse and national humiliation in May and June 1940.

The terrible impact of the 1914-18 war, particularly the psychological scarring left on the wartime generation, looms large. People are politically rudderless, losing faith in democracy and receptive to extremist solutions; the Jews are convenient scapegoats for the nation’s ills. Hartmann’s old family home is perhaps a metaphor for the Third Republic itself, the cracks in its structure gradually growing larger and its foundations undermined by the troubled builders’ shoddy workmanship.

Wonderful. Alas, my current read, a biography of the Nazi Rudolf Hess — Hess: The Fuhrer’s Disciple by Peter Padfield — most certainly is not. I don’t like giving up on books unless they are impenetrable or really, really boring. This is just a bad biography badly written, so I will plough on, especially as there is much I don’t know about Hess after his flight (as in ‘plane journey’, not ‘escape’) to Britain in 1941.

Books, TV and Films, March 2020

3 March

Back to one of my favourite novelists — Sebastian Faulks. Birdsong is probably his best-known book, but my favourite is Human Traces, a brilliant mix of invention, imaginative reconstruction and exposition of developments in psychiatry and psychoanalysis.

I have reached for On Green Dolphin Street, not a novel I have read before. In fact, when I opened the book at page one, I knew nothing about it whatsoever, except that it was set in the United States some time after the Second World War.

It’s a great feeling, reading from one page to the next with no idea about who the characters are, how the story will develop or even what the book is actually about. Early indications are that it involves a clever, fast-tracked diplomat whose career has stalled and whose problems are slowly but surely grinding him down, and his relationship with his devoted wife, who appears to have a gaping emotional hole in her life.

One sentence has baffled me, and I can’t work out whether it’s an error. Mary, the wife, is conflicted:

She could not establish an order of preference between the two; as well ask her to distinguish between a tree and a cloud: no crude ranking could reflect the reality of either.

8 March

I’m two-thirds of the way through On Green Dolphin Street. It’s another Faulks treat. He is a master at conjuring up a sense of time and place — be it the trenches of the Western Front, Occupied France during the Second World War or, in this case, New York at the end of the ’50s and beginning of the ’60s. Faulks is also a wonderful crafter of stories, adding layer upon layer as he goes and weaving threads of context and background that combine to form a convincing picture of the characters and their lives.

All the signature Faulks traits are here: the background research is thorough, time and place compellingly drawn and the attention to detail remarkable. It’s a whirlwind tour of delis and diners, apartment blocks and shops, bars and nightclubs — all to a backdrop of jazz (On Green Dolphin Street is apparently a Miles Davis classic).

9 March

Wonderful. Just wonderful.

On Green Dolphin Street is much more than just a conventional love story. It explores the different types of loving relationships — the unconditional love between parent and child; that life-changing first love; the love that grows and develops between lifelong partners; passionate and erotically charged love; and love between two soul mates.

The busy, bustling, labryinthine streets of New York are wonderfully drawn. Faulks is perhaps using the city as a metaphor — both its bewildering complexity and its dazzling possibilities. The Second World War is also a lingering presence, casting its long shadow years after the war itself is formally at an end.

After briefly worrying that the ending was turning into a rerun of the final episode of Friends, I found the conclusion satisfactorily unsatisfactory. It was, after all, an impossible dilemma that Mary faced.

A must-read.

15 March

I am in the middle of recording yet another version of The War of the Worlds. I have always loved the original Gene Barry film from the ’50s, didn’t really like the Tom Cruise version and avoided the 2019 three-part BBC mini-series. This is a multi-parter and stars Gabriel Byrne. As with all multi-part dramas, I will watch it when all the episodes have been shown.

That reminded me that I haven’t actually read anything by HG Wells, except for the rather intimidating opening page of The Time Machine — at least, it seemed intimidating when I was a teenager. In the meantime, I have reached for H.G.: The History of Mr Wells by former Labour leader Michael Foot.

I have a lot of time for Foot. Whatever one thinks of his politics, he is a great writer and his two-volume biography of Nye Bevan was a big part of my formative years. The Wells book is something else — more a literary biography, perhaps even literary criticism, rather than a conventional biography. I am fairly certain, for example, that at no point does the book say what H.G. actually stands for. Another extraordinary feature of the book is the length of some of the extracts from Wells’ writing — an extract from The Passionate Friends, for example, stretches for nine pages.

19 March

I finished the HG Wells biography today. Two immediate thoughts.

Firstly, how little I knew about him. I was aware that he had written a number of sci-fi classics (I could probably have named about five) and, of course, I knew that he was a socialist. Little did I know of the prodigious output that he kept up throughout his life. Nor did I know anything of his rather colourful life, particularly his many sexual relationships.

Secondly, it has not been a particularly easy read, taking a great deal of knowledge for granted. I was on solid ground with the history and politics stuff, but the many, many literary references were often new to me and not always easy to follow. Making a regular appearance throughout the book were Wells’ literary hero Jonathan Swift — someone I definitely need to learn more about — and, to a lesser extent, other literary figures such as Lawrence Sterne, William Hazlitt, George Bernard Shaw, James Joyce and (of course) George Orwell.

In conclusion, this is certainly not a book for someone looking for an introduction to Wells’ work.

28 March

After struggling through the Wells biography, I was looking for something to really carry me away. The Righteous Men by Sam Bourne did not disappoint. It’s a long-ish read —560 pages or so. I more or less kept to my 10% daily target except for the end. A sure sign of a gripping read, I finished off the last 100 or so pages in a day.

Sam Bourne is the nom de plume of Jonathan Freedland, my favourite Guardian columnist. I read and enjoyed The Last Testament a few months ago. He has a new book out — To Kill a Man — but I like to be systematic so I went for this one, his debut novel, published in 2006.

At least one of the ‘puffs’ — the endorsement quotes on the front and/or back cover — compares him to Dan Brown. Having only seen the films, I can’t comment on Brown’s writing, but he will do well to match Bourne/Freedland, whose books are pacy, gripping and superbly crafted. In The Righteous Men, a mass of what the reader assumes to be minor detail, there to add colour or to flesh out a character’s backstory, is liberally sprinkled throughout the opening pages, only to take on huge significance as the plot unfolds.

Both of the Sam Bourne books I have so far read have had religion at the heart of the plot. Each has been exceptionally well-researched, delving into ancient beliefs and traditions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Each one raises interesting and important questions about the nature of religious faith and about religious fanaticism. I will say no more!

The Righteous Men has certainly whetted my appetite for my next read, John Barton’s highly acclaimed A History of the Bible.

British Politics and Failures of Leadership

Oh, to be in England

Robert Browning

Now that April’s there

Well, almost there. At time of writing, the end of March beckons. Our gardens and open spaces are reawakening, the evenings are stretching their limbs, the weather is more friendly. Time to look forward to summer? Alas, no. Like an evil sorcerer, Covid-19 has cast its malignant spell over us all, playing tricks with our perceptions of time itself. We are in a race against time to hold back and then defeat the disease, but rarely has time seemed so relative. For those on the front line, under-resourced and overworked, time must be a blur. For the rest of us, meanwhile, confined to our homes for much of the day practising self-isolation or social distancing, time is slowing.

We are currently in partial lockdown. Everything not directly coronavirus-related seems like an irrelevance. But politics and the political process do not stop (though parliament itself has now risen for four weeks). The government still governs and, perhaps more than ever, MPs of all parties have a duty to fulfil one of their key functions — scrutinising those in power and holding them to account.

Our government — like all governments around the world — is being tested like never before in peacetime history, led by a prime minister only months into the job. What follows is not about the government’s handling of the current crisis, but it is a reminder that, when we make our choice at the ballot box — or when we don’t bother, for that matter — we have no idea what perils await those we elect. Events, dear boy. Events.

It is a sobering thought, one that suggests an interesting question: which UK administration ranks as the worst of modern times — ‘worst’ in the sense of ‘dysfunctional, not up to the job’?

The Eden government (1955–57) made a calamitous error of judgement over Suez, and Eden was out of office before really getting his feet under the prime ministerial table. The short-lived Douglas-Home government (1963–64) is but a footnote in the history books. The 1970s was a troubled, tempestuous decade but — though we might argue all day about strategic direction and individual policies — it is less easy to make the case for gross incompetence. Rather the opposite, in fact.

For a long time, my answer to the question would have been the government of John Major. For someone who first took an interest in politics in the Thatcher era — with its endless refrain of ‘competent Conservatives / incompetent Labour’ — it was hard to resist at least a frisson of schadenfreude watching a Conservative government taking ineptitude and mismanagement to new levels — the Black Wednesday debacle, in-fighting over Europe (the prime minister characterised fellow cabinet members as “bastards”), the citizen’s charter, back to basics.

A sorry list of mostly self-inflicted woe.

So the award used to go to John Major’s government … until, that is, Theresa May came along in 2016, picking up the pieces of David Cameron’s twelve-month-long “strong and stable” government. She played a fiendishly tricky hand badly, like a poor poker player on a run of rotten luck. Brexit brought paralysis; like dementors in Harry Potter World, it sucked up all the government’s energy and left devastation in its wake.

To switch metaphors, May charted an impossible course with her ridiculous red lines and appointed hardline Brexiteers to steer the ship. Parliament was treated with utter disdain until the government lost its majority and was forced to concede ground in one area after another. Inflexibility was the watchword, her lack of even basic interpersonal skills brilliantly captured by John Crace’s Maybot caricature in The Guardian.

For nearly three years May’s government tacked to the right rather than seeking a viable way forward, a parliamentary compromise around which elements of all parties might coalesce. This sorry chapter will figure prominently in future histories of the Conservatives — the party of Stanley Baldwin, Harold Macmillan and Edward Heath shunning pragmatic, moderate centrists such as David Gauke, Ken Clarke and Dominic Grieve and instead embracing the likes of Jacob Rees-Mogg, Mark Francois and Priti Patel, blinkered, ludicrous and repulsive in equal measure.

Meanwhile, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn — elected, and then triumphantly re-elected, by an unprecedented number of party members, many of them recent recruits — failed to lay a glove.

For a lifelong protester, Corbyn is a surprisingly poor public speaker. He is leaden and flat-footed at the Commons despatch box. With Prime Minister’s Questions the only bit of parliament that many voters see, this matters. Time and again he had May’s hapless front bench at his mercy; time and again he proved incapable of delivering a decisive blow. It was backbench heavyweights who hit hardest — the likes of Hilary Benn and Yvette Cooper. The single most electrifying contribution of the last parliament was arguably Margaret Beckett’s speech of 4 December 2018 during one of the many, many Brexit debates.

I have argued elsewhere that Brexit confronted Labour with an impossible conundrum, but Brexit alone did not undermine Corbyn. The fact is, he has proved to be a poor leader. Corbyn is a campaigner, a maverick, an outsider; the march, rally or hastily assembled protest meeting is his comfort zone. He thrives on berating others for their lack of ideological purity but is deeply uncomfortable making the hard choices that leadership requires. To (slightly) rework an old saying, to lead is to choose.

The 2019 election result was neither shock nor surprise: despite nine years of austerity, the implosion of Cameron’s government and three years of utterly shambolic Brexit negotiations, the Labour Party consistently scored badly in opinion polls. The election campaign itself was awful — flat and uninspiring, as wet as the late-autumn season. We read of resources directed to the wrong seats, of poor campaign coordination. We can point to ill-judged policy announcements like broadband and WASPI women, and of a car-crash interview with Andrew Neil. But this runs the risk of deflecting the blame onto party officials or his de facto deputy, John McDonnell. The stark reality is that, in this highly presidential campaign, Corbyn wasn’t up to the job.

With so much hindsightery, it’s worth quoting a tweet from the excellent political journalist Steve Richards. It was written on 17 November, four weeks before election day:

Historians will wonder with good cause why J Corbyn and J Swinson gave B Johnson an election on the date he wanted and at the height of his prime ministerial honeymoon. They were leaders in a hung parliament with considerable powers to determine an election timing and much more.

Steve Richards, political journalist, 17 November 2019 (on Twitter)

Historians will also speculate on what led them to take the fateful decision.

Perhaps it was hubris — pride, arrogance, excessive self-confidence — which, as the ancient Greek playwrights worked out, always ends badly. Facing the pitiful May government in parliament, rarely a speech or intervention seemed to end without an impassioned demand for an immediate general election. But like Bernie Sanders predicting the “beginning of the end” for Trump after the New Hampshire primary in January 2020, it was empty rhetoric, nothing more than bluff and bluster, the cut and thrust of parliamentary swashbuckling. Along came Johnson and called their bluff.

The Liberal Democrats’ support for an election at least made some kind of sense: the party had a clearly articulated (if controversial) position on the central Brexit issue; they were for a time polling above 20% and had performed well in the earlier European elections; and they seemed genuinely to be on a surge, their tally of MPs growing by the week due to regular defections from the two main parties.

Add to the mix a sprinkling of groupthink. All leaders surround themselves with like-minded thinkers and ‘yes’-people. But the Corbyn phenomenon has been something else, more akin to a cult. Consider the signs: a devoted band of followers; a narrative setting out simplistic explanations for what is wrong with the world and equally simplistic solutions; intolerance of dissent and excoriation of non-followers. How ironic, then, that another of the features of a cult — a charismatic, supposedly omniscient leader — is something that Corbyn most assuredly is not.

The takeaway from the 1992 election was that it was John Major’s soapbox ‘wot won it’ for the Conservatives, an unlikely victory when defeat seemed on the cards: good old John, man of the people, doing things the old-fashioned way etc. And so, right on cue on the first day of the 1997 election, there he was on his soapbox, as if this would somehow make a 20-point poll deficit magically disappear. The strategy had spectacularly failed to differentiate between cause and correlation: A followed by B does not necessarily mean that A caused B.

Fast-forward to the 2019 election. The thinking seems to have gone something like this: Corbyn had a good campaign in 2017 (let’s ignore the inconvenient fact that Labour lost) so just do the same thing this time around. Let Corbyn be Corbyn, to borrow an idea from The West Wing: set him free on the campaign trail, meeting real people, generating a sense of momentum (sic) and all will turn out for the best. In other words, ignore the clear signs of popular disillusionment after years of parliamentary paralysis, ignore the polling evidence, ignore the catastrophic impact of the antisemitism charge on the leadership’s credibility, ignore the time of year — the short days and long, dark evenings, the cold, the rain. All will turn out for the best. Except, it didn’t.

In a few days — voting ends on 2 April — the Labour Party membership will have chosen a new leader and deputy leader. An election campaign that feels like it has been going on forever, without at any point igniting the interest of the wider public, seems like an irrelevance in the midst of a global emergency. It is, in fact, anything but. As was noted in the opening few lines, politics and the political process go on, and there is important work to do in holding the government to account. But there is another reason too. In the 1920s the Liberal Party went through a catastrophic status update — from one of the two great parties of government to third-party irrelevance. The next Labour leadership team may well determine whether the Labour Party goes the same way in the 2020s.

Click to read some thoughts on Brexit, the 2019 election and the state of British politics.

Photo at the head of this blog: Getty. Retrieved from https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/elections/2019/01/who-ll-blink-first-stand-between-jeremy-corbyn-and-theresa-may

Books, TV and Films, February 2020

3 February

I finished A Divided Spy by Charles Cumming the other day. That means I managed to read four books in January, putting me comfortably ahead of my target. A nice balance, too, of fiction and non-fiction, academic and non-academic, challenging and ‘lighter’ reads etc.

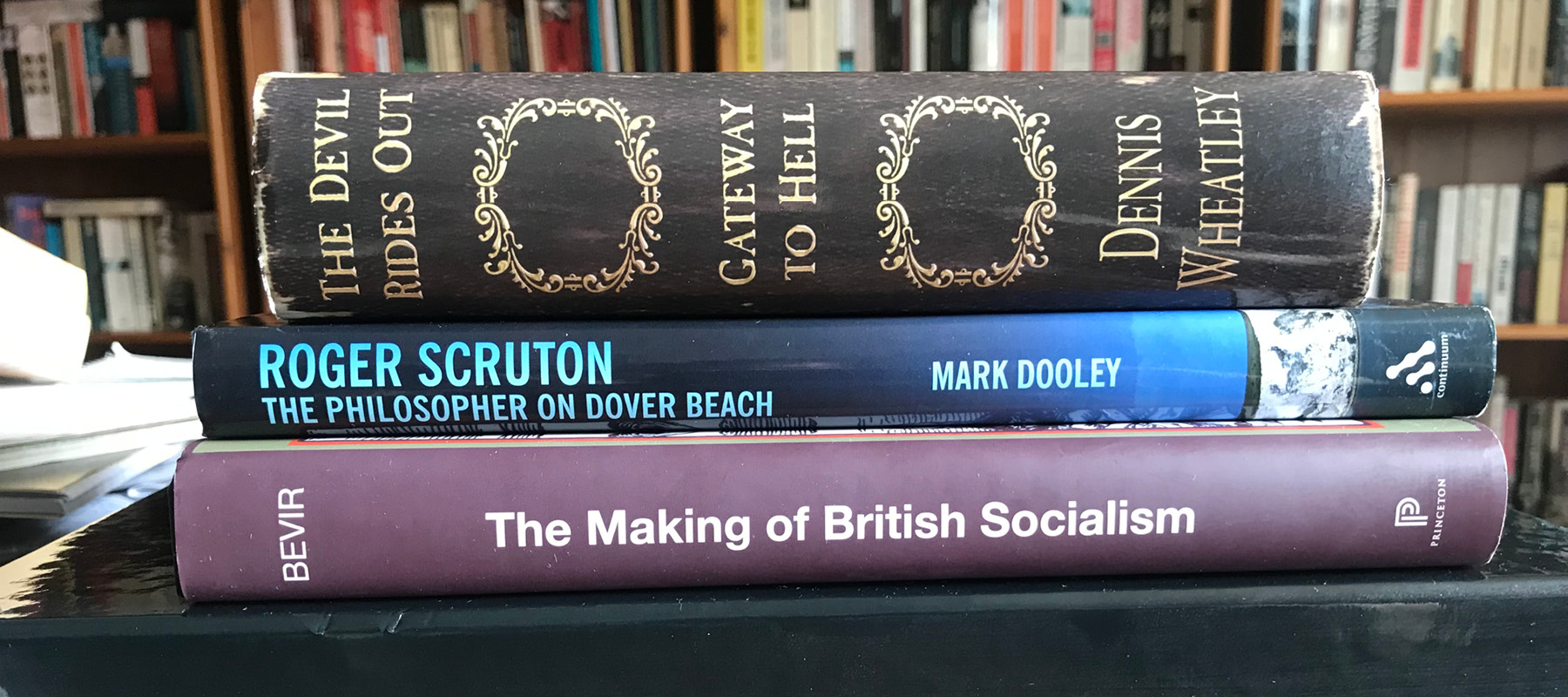

Reading Peter Ackroyd’s Dominion brought me back to thinking about the development of socialism and the origins of the Labour Party. I am re-reading The Making of British Socialism by Mark Bevir, a book I first read perhaps five years ago, possibly more.

It’s a tough book to get into, not really one for the general reader. It’s essentially a collection of academic papers pulled together into some kind of coherent whole. It is essentially a history of ideas but, as I say, written for an academic audience, with its talk of “retrieving alternative socialist pasts” and “narrating those pasts”. I gulped when I saw the sub-heading ‘Theory’, not really my thing when it comes to history. Welcome to “aggregate concepts”, “naive empiricism”, “reification” and so on.

8 February

The Making of British Socialism is proving an interesting challenge. It’s extremely repetitive in places — almost certainly due to its origins as a series of academic papers — which was annoying at first until I realised that the repetition was actually helping with the reinforcement of key ideas and aiding understanding.

The first couple of chapters were tough-going, with lots of terms and concepts unexplained. To take just one example, it assumed an understanding of the distinctions between popular radicalism, liberal radicalism and Tory radicalism.

As the book goes on, however, each of the key political ideas and concepts is being carefully unpicked, explained and analysed. One or two things still left me none the wiser — the discussion of German idealism, for example (nothing new there) — but most of the chapters have been rewarding and enlightening.

On a separate note, the BBC’s latest Agatha Christie adaptation — The Pale Horse (based on her novel of 1961) — starts tomorrow. A must-watch.

13 February

I finally finished the origins of British socialism book — a couple of days behind schedule. It’s been a busy few days, and I have found it difficult to keep to my 10% target.

It was definitely worth re-reading. At a time when politics is in a mess and the future direction of the Labour Party — even its very survival — up in the air, it was a useful exercise going back to the core ideas and values that animated progressives in the left’s early days. I particularly enjoyed reading about the ideas of the ethical socialists, who eschewed a class-based analysis, and economics and politics more generally, in favour of an approach based on spiritual renewal. Call it naive and impossible to achieve, but it’s a compelling vision of what the ideal society might be like.

One of the cable film channels showed To the Devil a Daughter last Friday, a 1976 film based on a Dennis Wheatley novel. It’s a somewhat controversial film for a number of reasons, and Wheatley disowned it. It’s rarely shown, certainly far less often than The Devil Rides Out, which I count as one of my all-time favourite films. I was meaning to re-read one of these two books before writing a blogpost on the subject, so this has sealed it. My next read.

16 February

Blimey. I thought Agatha Christie’s writing was dated, but Wheatley takes it to another level. The Devil Rides Out was first published in 1934. Like Christie’s Poirot, we’re mixing exclusively with the rich and privileged. Much of the characters’ wealth is obviously inherited, though Simon and Rex’s considerable incomes appear to be from finance and banking. Simon, we are told early on, is no longer living at his club. Max, meanwhile, is the Duke de Richleau’s ‘man’ — in other words, his butler. Indeed, butlers, maids, chauffeurs, cooks and nannies are an intrinsic part of this world. Globetrotting, too, is the norm: Rex, for example, has happened to notice a beautiful stranger called Tanith, who becomes central to the plot, in Budapest, New York and Biarritz in recent times.

The biggest shock is the use of language and the underlying attitudes it reveals. The meaning of words changes over time, of course, but it surely isn’t just poor writing craft that makes the use of the word ‘queer’ five times in the opening five pages seem alarming.

In Wheatley’s descriptions of the sinister guests at Simon’s party (it turns out they’re all satanists), the juxtaposition of each individual’s racial background with a list of their unpleasant characteristics is unfortunate to say the very least — the “grave-faced Chinaman … whose slit eyes betrayed a cold, merciless nature”; “a red-faced Teuton, who suffered the deformity of a hare lip”; a “fat, oily-looking Babu”.

To modern sensibilities, the most extraordinarily inappropriate exchange, however, goes as follows:

[Duke]: … he reminded me in a most unpleasant way of the Bogey Man with whom I used to be threatened in my infancy

[Rex]: Why, is he a black?

I kid you not.

20 February

I read about 80 pages of The Devil Rides Out last night — staying up late, as is becoming a habit with exciting novels, to finish the story.

The book improves considerably as it goes on. The well-known pentacle scene — when Mocata sends various manifestations of evil to claim back Simon — is excellently written and genuinely unsettling even for the modern reader. Up to this point, the later film roughly follows the book, but the final third is completely reimagined — presumably on cost grounds.

The Eatons’ daughter has been kidnapped by the satanists and is to be offered as a sacrifice in a black mass. In the film, the location of the mass is close by and easily accessible. In the book, on the other hand, our heroes are forced to traverse the continent of Europe. Handily, Richard Eaton has an aeroplane parked at the bottom of the garden. Cue breathless flights to Paris and then to an inhospitable mountain range in Greece for the final showdown between good and evil.

21 February

With the sad news of the death of philosopher Sir Roger Scruton, it felt right to pick out something of his as my next read. I have always found Scruton a curiously compelling figure. My politics are very different from his, though he is far from being an unthinking flag-waver for the right wing of the Conservative Party. His conservatism is grounded in his philosophical beliefs; unlike many on the right nowadays, he takes the ‘conserve’ of conservatism literally. He also writes beautifully.

25 February

I actually plumped for a book about Sir Roger Scruton rather than one written by him, though quotes from his many writings are used extensively. Roger Scruton: The Philosopher on Dover Beach by Mark Dooley analyses Scruton’s core ideas. Dooley is a fully paid-up Scrutonian, so there’s little in the way of critical engagement. Rather, the book serves as a useful introduction. It’s rather a slight book — 180 pages, including extensive end-notes — and hardly the “major study” promised on the dust jacket.

Organised into five chapters, it takes the reader through Scruton’s thinking on matters such as aesthetics, sexuality, religion and culture. Dooley returns repeatedly to notions of the Lebenswelt (our ‘lived experience’), the sacred, home and community, and belonging. He pays particular attention to where Scruton’s views clash with other thinkers, especially those on the left.

A useful read, helping me understand Scruton’s thinking better — and one that makes me want to search out more of Scruton’s output.

By the way, there was an excellent obituary of the historian Zara Steiner in The Guardian the other day, written by Sir Richard Evans. I first came across her when my professor recommended her Britain and the Origins of the First World War to me for my dissertation at university.

Evans is great. His recent obituary of Norman Stone was absolutely brutal. Ouch!

Books, TV and Films, January 2020

1 January

New year — new decade — new resolution … a reading log or diary. Let’s see how this goes. Also thinking of setting myself a target of a book every ten days, equating to 36 books over the year. That means reading 10% of each book every day — a tall order for anything over about 300 pages. Seriously toying with the idea of cancelling my Guardian subscription (it takes me about two hours to read it).

I am starting the new year with a new read (or rather, re-read): Citizens to Lords by Ellen Meiskins Wood.

I finished my Christmas treat — The Burning Chambers by Kate Mosse — a few days ago and ended the year with a few Sherlock Holmes short stories (inspired by a comment during the election campaign by John Crace in The Guardian).

I now have only the very final Holmes short story to go — The Adventure of the Retired Colourman. I read almost the complete set of Conan Doyle Holmes books last year, most of them before watching the relevant ‘Jeremy Brett’ dramatisation. I may go back and re-read the short stories again this year — easy to dip into for half an hour or so. There are 56 of them.

The first episode of the latest Dracula dramatisation is on BBC1 tonight; it involves Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss, so should be excellent. That’s reminded me: I must get round to reading Frankenstein this year.

2 January

Last night, I read the very final Holmes short story, The Adventure of the Retired Colourman — so a milestone of sorts. I don’t know whether I have a memory of the TV adaptation or whether it’s a growing familiarity with Conan Doyle’s style, but I guessed the significance of a few of the plot ingredients like the newly painted house and the telegram from the vicarage. Having said that, I was convinced that the mysterious spectator outside the house was Holmes in disguise.

Definitely up to Conan Doyle’s usual standard, and so much more enjoyable as a read than the first Poirot novel, which I read last year. Kate Mosse was singing Agathe Christie’s praises on Twitter; she’s just re-read the Miss Marple books over Christmas. I must read more Poirot to see if the quality improves.

5 January

Enjoying Citizens to Lords, a history of political thought in ancient and medieval times. Putting the political angle aside for a moment, it’s always enjoyable to read a Marxist writer who writes fluently and intelligibly. That’s one of the reasons why I always enjoy reading Ralph Miliband and Eric Hobsbawm. I first read it about four years ago, but I am finding it much easier to grasp this time around, having in the meantime read some reader-friendly introductions to the history of philosophy, particularly the brilliant The Dream of Reason by Anthony Gottlieb.

Richard Dawkins (a fan of audio books, which have never appealed to me) tweeted the other day about listening to Paperweight by Stephen Fry. He sang the praises of a Holmes short story that Stephen wrote. I must read that; his novels Making History and The Stars’ Tennis Balls are right up there for me.

10 January

I finished Citizens to Lords yesterday, having managed to keep to my 10%-a-day target. So much packed into its 236 pages. Yes, it’s written from a Marxist perspective but it’s very readable, accessible (as long as you have a working knowledge of political theory and Ancient Greek philosophical ideas), erudite and compelling, with something illuminating on every page. Looking forward to reading the companion volume, Liberty and Property, at some point in the coming weeks and months.

Listening to a couple of James Bond dramas on BBC Sounds — what a discovery … the dramas, not the app! — has led me back to A Colder War by Charles Cumming. It’s the second of his Thomas Kell trilogy; I really enjoyed the first one, A Foreign Country, last year.

15 January

The morning after the night before. I stayed up late to finish A Colder War. A gripping read; thoroughly enjoyable. It got to about 10pm and decision time: stay up and read a bit more, stay up until I finish it, or leave it until tomorrow. It was a no-brainer in the end. Fiction can get you like that: I felt exactly the same way reading Stephen King’s 11.22.63 a few years ago. I am determined to read more page-turning fiction this year.

I discovered Charles Cumming through The Trinity Six, a novel about a supposed sixth member of the Cambridge spy ring. A Colder War is set in the same fictional landscape as his earlier A Foreign Country and features an out-in-the-cold SIS spy called Thomas Kell.

It’s not as well written as le Carré — what is? — and I felt myself giving him the benefit of the doubt after reading things like “Giles, a man so boring that he was dubbed ‘The Coma’ in the corridors of Vauxhall Cross”. But the writing is generally much better than that, and the structuring, plotting and sense of place are all excellent. Plus, there’s tons of spycraft to enjoy. The extended description of a surveillance operation through London is brilliantly told.

20 January

Thoroughly enjoying Dominion, Volume V of Peter Ackroyd’s The History of England series, this one covering the period from 1815 to 1900. I actually read two thirds of it when I first bought it but then put it to one side, probably to read something ‘essential’ that was newly published. Can’t remember what.

I originally bought Volume I — Foundations — from a shop specialising in remaindered books. I wanted something accessible, as my knowledge of early history is woeful. This is broad-brush history, written by someone with highly developed literary sensibilities: line one of page one refers to Vanity Fair and there are also references to Byron, Southey, Dickens and Wilde within the first few pages.

There are no footnotes or end-notes and the historian in me squirms somewhat when encountering sweeping generalisations like: “They [the English people] differed from their predecessors and their successors with their implicit faith in the human will.” But it is wonderfully written and a joy to read.

25 January

I finished Dominion today. Ackroyd is simply remarkable: his output is prodigious and ranges widely across disciplines, though London is never very far away from his thoughts.

He writes wonderful prose — the pen-portraits, in particular, are often engagingly drawn with an eye for amusing, often absurd, detail. Sometimes, however, his style simply doesn’t suit a work of serious history: “[Disraeli] could have flattered his way out of a condemned cell and stolen the axe.” Ugh.

On the other hand, there are echoes of the great AJP Taylor in sentences like: “The conflict did not assist or make any military reputations, and the war itself had emanated from the fear of an attack which was never contemplated and a threat which barely existed.” Therein, I suppose, lies the problem: it’s a wonderful read but is it good history — reasoned, balanced, nuanced?

One wonders, too, whether age is finally catching up with him. His daily routine apparently involves — certainly until recently; he may have finally slowed down — working on three projects at the same time, twelve-hour working days ending with copious amounts of alcohol, seven-day working weeks.

Something surely has to give. This is an annoyingly London-centric history, presumably reworking previously researched material and quoting, sometimes at considerable length, from primary sources. In a book of this size, every word counts: key people, events and developments merit no more than a chapter, maybe a page, perhaps only a paragraph or two. And yet Ackroyd devotes two full pages quoting at length from an 1894 book about the Golden Jubilee of 1887 — its focus, no surprise, the people of South London.

Anyway, I await the final volume with interest. Meanwhile, time for the third in the Thomas Kell spy trilogy by Charles Cumming.

30 January

One month in and my new year reading resolution is going well. I am managing to keep to my 10%-a-day target … exceeding it, in fact. That’s partly because I chose medium-sized books this month rather than doorstoppers. It has also helped that my two fiction choices this month — both by Charles Cumming — have been page-turners.

A Divided Spy is the last of the Thomas Kell trilogy by Charles Cumming. I read about 100 pages a couple of days ago. It was about 8pm and the thought did cross my mind: 150 pages or so to go … do I pull an all-nighter? A daft idea, but a sign of a thoroughly enjoyable book.

Brexit, the 2019 Election and the State of British Politics

For someone who locates himself somewhere on the political left, the outcome of the 2019 general election was shattering and sobering, though surely not entirely unexpected: a substantial Commons majority for the Conservatives — memo to self: look up the definition of ‘landslide’ — and, what is worse, talk of ‘powerful’ mandates, ten years of Conservative rule and a ‘Boris revolution’. Note: this is the sole reference to ‘Boris’ and deliberately placed in inverted commas.

Unfortunately, election promises — especially Johnson promises — are, like many Christmas toys, cheaply made and easily broken.

Diogenes

It is possible that Johnson’s large parliamentary majority and the largesse promised to, and seats secured in, formerly solid Labour areas will free him of the urge to tack to the right in order to satisfy the whims of erstwhile ERG allies. Unfortunately, election promises — especially Johnson promises — are, like many Christmas toys, cheaply made and easily broken. We will know more after Javid’s next budget (expected in February 2020) and the forthcoming multi-annual spending review, but the early signs do not augur well.

The revised EU Withdrawal Agreement largely stripped away previous guarantees of workers’ rights, regulatory standards compliance and parliamentary scrutiny. Meanwhile, though a New Year’s Eve announcement of a 6.2% increase in the minimum wage is welcome, earlier promises to increase the minimum wage to £10.50 over five years now come with a small-print caveat — “provided economic conditions allow”.

The Labour Party in 2019 faces a threat to its existence as grave as that of 1979-83. The loss of heartland seats such as Bolsover is historic …

Diogenes

Chapter 22 of (probably) my favourite set of political memoirs — Denis Healey’s The Time of My Life — covers the years after Margaret Thatcher’s election in 1979: he called it Labour in Travail. The Labour Party in 2019 faces a threat to its existence as grave as that of 1979–83. The loss of heartland seats such as Bolsover is historic, though we don’t of course yet know if this represents a permanent shift in the political tectonic plates.

The facts and figures are not encouraging for Labour supporters. Since Harold Wilson’s 98-seat majority in 1966 — 53 years ago, at the time of writing — Tony Blair is the only Labour leader to be elected with a parliamentary majority. Assuming that the Fixed-Term Parliaments Act is repealed, Labour’s next realistic chance of forming a majority government is likely to be 2028 at the earliest, 23 years after Blair’s last victory in 2005. How we lefties hooted in 1997 when the Conservatives were wiped out in Scotland, with Labour winning 56 of the 72 seats. In 2019, Labour won just a single seat out of the available 59.

The first time I didn’t vote Labour — I usually do, with a greater or lesser degree of enthusiasm — was my first general election in 1987. A student at Reading University (which is actually in the Wokingham constituency), I voted tactically for the SDP–Liberal Alliance candidate, defiantly denting John ‘Vulcan’ Redwood’s 20,000-ish Conservative majority by one.

December 2019 was the latest time that X didn’t mark the spot. I certainly wasn’t the only wandering voter, though I doubt too many people joined me in spoiling my ballot paper by scrawling None of the above. Bring back Tony Blair across it.

The influence of the media

Anti-Corbyn or anti-Labour media bias as an explanation for Labour’s defeat — the term ‘media’ used here to refer to the highly regulated broadcast media, the privately owned print media and social media, which is largely unregulated — lacks plausibility.

It is platitudinous to argue that howls of anguish from both sides means that the BBC has ‘got it about right’. Equally, the claim of overt broadcaster bias is risible …

Diogenes

For every complaint about an anti-Labour agenda or a bias against Corbyn, the attack-dogs of the right make exactly the opposite charge about the broadcast media — though not, of course, about the print media — particularly about the BBC. It is platitudinous to argue that howls of anguish from both sides means that the BBC has ‘got it about right’. Equally, the claim of overt broadcaster bias is risible, from whatever quarter it comes.

Andrew Neil’s skewering of Corbyn needs to be seen alongside the same broadcaster’s no-holds-barred interviews with other party leaders and particularly his five-minute empty-seating of Johnson. Andrew Marr’s fussy interview with Johnson generated 12,000 viewer complaints (some, at least, no doubt submitted at the behest of CCHQ).

For all the accusations of an institutional liberal-left bias at the BBC, we should remember that there are plenty of former Conservative Party personnel who hold key positions in the organisation. I wonder what Sarah Sands and Nick Robinson — both formerly prominent Conservative supporters — think of the (probably) Dominic Cummings-inspired boycott of the Today programme by senior ministers.

Perhaps doubters from both sides need to be force-fed an hour of Fox News.

The print media, meanwhile, has always been overwhelmingly anti-Labour in modern times. When, in 1992, a Sun front-page headline requested that the last person to leave Britain in the event of a Labour victory switch off the lights, the paper was selling around 4 million copies per day compared to around 1.4 million in 2019. Newspapers and their owners still wield influence, of course — it is a worry, for example, how much the daily television news agenda is influenced by newspaper headlines — but influence in what circles?

Social media feeds on our algorithmically determined preferences and prejudices, generating sensationalist soundbites and clickbait headlines, devoid of context or even of meaning. Lies are peddled as fact; ludicrous assertions are left unchallenged, bouncing around the echo chamber.

Diogenes

Many ‘ordinary’ voters — as opposed to political geeks and those who inhabit the Westminster bubble — increasingly consume their news via social media rather than from newspapers or TV news. Sadly, this is almost certainly damaging our political culture. Social media feeds on our algorithmically determined preferences and prejudices, generating sensationalist soundbites and clickbait headlines, devoid of context or even of meaning. Lies are peddled as fact; ludicrous assertions are left unchallenged, bouncing around the echo chamber.

But there is no reason why this development — good or bad — should disadvantage the Labour Party over and above their rivals: if anything, social media demographics ought to work in Labour’s favour. An excellent media analysis in the Guardian quoted Dr Richard Fletcher of the University of Oxford’s Reuters Institute: “One of the clearest differences is that most of those on the left prefer to get news online, and most of those on the right prefer to get it offline.”

But social media benefits those with the best lines, and in 2019 the best line of all consisted of just three words: Get Brexit Done.

Brexit

One Friday evening sometime during one of Theresa May’s parliamentary debacles — it’s impossible to pinpoint the specific one; there were so many — a brief pub conversation with a friend of a friend about the dismal performances of our local football team somehow strayed into Brexit territory. That I should be discussing politics at the bar of my local with someone I barely know is itself an indication of the extent to which Brexit weaves its malign magic.

And yet this shameless hyperbole was offered up so calmly, so matter-of-factly, as if pointing out a plain, unremarkable, common-sense fact along the lines of night following day, Saturday following Friday.

Diogenes

I was dumbfounded to hear him — an ordinary, unassuming chap in his seventies: friendly, mild-mannered, level-headed — assert that we (the British people) have been slaves for 40 years — yes, slaves. Stunned by this, my immediate reaction was ridicule, to mimic walking around as if lugging a ball and chain. And yet this shameless hyperbole was offered up so calmly, so matter-of-factly, as if pointing out a plain, unremarkable, common-sense fact along the lines of night following day, Saturday following Friday.

The issue of Britain’s relationship with Europe has obsessed the political classes since the days of ‘splendid isolation’ and long before; most ‘ordinary’ people, on the other hand, have been completely uninterested except, obviously, in times of war. An Ipsos MORI poll conducted during the 1992 general election campaign — the year of the Maastricht Treaty — asked voters to identify their top two or three issues of concern: 4% cited Europe and 1% cited immigration. As recently as 2010, an Ipsos MORI analysis of that year’s general election suggests that, though 14% cited asylum / immigration as a key issue, Europe was not one of the sixteen issues that registered at least 3%.

… the impact of Brexit on the Conservative Party has in some respects been at least as transformative, not to say revolutionary, as the leadership of Margaret Thatcher.

Diogenes

The Europe question has bedevilled both main political parties — it was Labour’s Harold Wilson who called the referendum in 1975, suspending collective cabinet responsibility for the campaign’s duration in an attempt to keep the party together — but the impact of Brexit on the Conservative Party has in some respects been at least as transformative, not to say revolutionary, as the leadership of Margaret Thatcher.

Anti-EU zealots, long in the wilderness, now wield significant influence at the highest levels, including in Cabinet. The Conservatives’ Brexit strategy over the last three years has placed severe strains on our constitutional arrangements and conventions. Moderates such as Ken Clarke and Dominic Grieve have effectively been cast adrift, some even expelled from the party. Astonishingly, during the election campaign, a former Conservative prime minister and deputy prime minister — John Major and Michael Heseltine respectively — urged voters to vote tactically against official Conservative candidates, with Major earlier threatening to take the Conservative government to court.

Listening to the government’s repeated insistence on the need to leave the EU single market in order to forge new trade deals around the world, it is worth remembering that Conservatives’ Euro-scepticism (as it used to be termed) was always political in origin and nature rather than economic — hostility to what they saw as the federalist project of ever-closer union. It was, after all, Margaret Thatcher who negotiated the Single European Act in the 1980s that paved the way for the single market and, though this is seldom mentioned in Thatcherite circles, monetary union.

In an interview with Sky News as recently as 2013, Boris Johnson said: “I’d vote to stay in the single market. I’m in favour of the single market.” In the same year, arch-Brexiteer Andrea Leadsom said that leaving the EU would be “a disaster for our economy and it would lead to a decade of economic and political uncertainty at a time when the tectonic plates of global success are moving.”

Suddenly, any such ‘Norway-style’ arrangement keeping Britain in or closely aligned to the single market has become a betrayal. This post-referendum Conservative and Unionist government — to give the party its full title — has also agreed a Withdrawal Agreement that puts in place separate customs arrangements for Northern Ireland. This is despite Johnson specifically and unequivocally denouncing the idea at the DUP annual conference in 2018.

Without doubt, the government’s Brexit policy has already severely weakened the Union and could potentially lead to its break-up. The Conservative Party of old used to accuse the left of constitutional vandalism: they, by contrast, posed as guardians of the integrity of the United Kingdom.

No longer, it seems. According to a YouGov poll in June 2019, a clear majority of Conservative Party members are prepared to countenance the break-up of the Union in order to achieve Brexit — 63% with respect to Scotland and 59% with respect to Northern Ireland. Extraordinary stuff.

From nowhere, Europe — more specifically our relationship to it — has become an existential issue for the general public, as bizarre and irrational in the visceral reactions it generates as arguments over religion in days of old …

Diogenes

But Brexit has spread its poison far beyond the Conservative Party. From nowhere, Europe — more specifically our relationship to it — has become an existential issue for the general public, as bizarre and irrational in the visceral reactions it generates as arguments over religion in days of old, when disagreements over such arcana as consubstantiation and transubstantiation, and justification by deeds or by faith alone, were often literally a matter of life and death.

Rather than healing divisions, as David Cameron had naively hoped, the legacy of the referendum has been three years (and counting) of anger, frustration and bitterness and, if claims that this was ‘the Brexit election’ are perhaps overstated — at least to the extent that issues such as health, the climate crisis and leaders’ trustworthiness were also widely debated — there seems little doubt that Brexit swayed many people’s vote.

… ‘Brexit’ stands, at least in part, as a proxy for other issues — from concrete concerns about immigration, about job insecurity and poverty, and about haves and have-nots to less tangible feelings of displacement and disconnect, of unease in changing times and of dissatisfaction with our political institutions.

Diogenes

On the reasonable assumption that people don’t deliberately vote to make their country poorer, ‘Brexit’ stands, at least in part, as a proxy for other issues — from concrete concerns about immigration, about job insecurity and poverty, and about haves and have-nots to less tangible feelings of displacement and disconnect, of unease in changing times and of dissatisfaction with our political institutions.

Concerns such as these resonate above all in poorer communities, particularly the former industrial heartlands that have largely missed out on the benefits of economic modernisation and globalisation — in other words, Labour-voting communities. Here was Labour’s Brexit conundrum: an instinctively Remain party whose traditional base largely voted to leave. It is one that the party leadership singularly failed to solve.

The question of Brexit quickly became the unilateral nuclear disarmament issue of our times, exposing a key fault line in the party’s cross-class coalition of support. Like unilateralism in the 1980s, opposition to Brexit was a policy espoused passionately and instinctively by Labour’s middle-class membership — young, university-educated, city-based, cosmopolitan in outlook and lifestyle — but largely alien to its traditional working-class base.

But Brexit alone cannot explain Labour’s catastrophic election …

Click here to read more thoughts about British politics and failures of leadership.

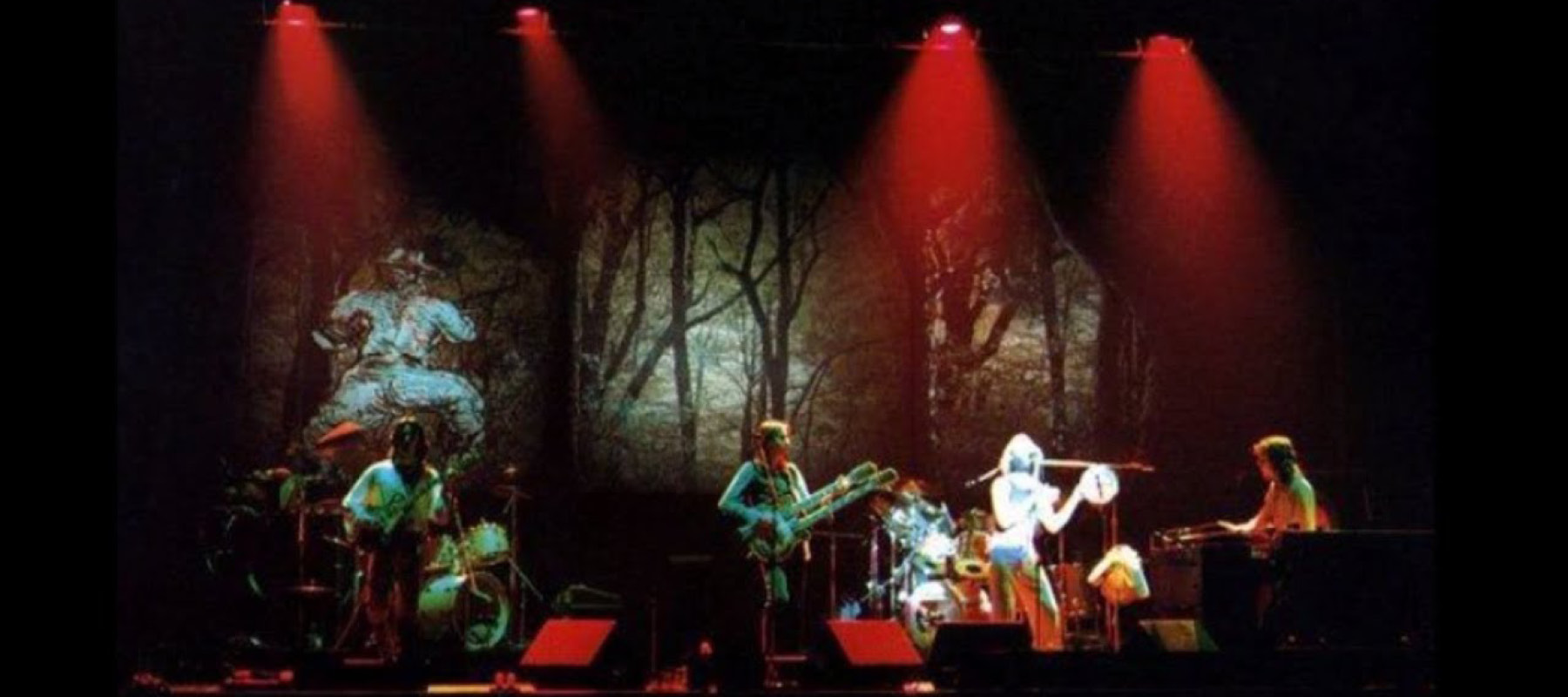

London 1976: Genesis Bootlegs

It is June 1976, the beginning of a long and swelteringly hot British summer. The backdrop is one of industrial decline, financial crisis and political turmoil, and the music scene is soon to experience a not-unconnected upheaval of its own.

Deep Purple’s brilliant but moody guitarist has left the band. Emerson, Lake and Palmer are on an extended break, having released no new material since 1973 — and fellow prog-rock giants Yes, none since 1974. Led Zeppelin are battling both the UK exchequer and personal demons: they are tax exiles and Robert Plant is lucky to have survived a serious car crash. Pink Floyd are holed up at their new Britannia Row Studios in London, writing their bleakest album to date.

In short, rock music’s titans are lacking a sense of direction, and punk is about to emerge from the underground to chart a very different course.

Genesis are also undergoing a revolution of sorts, their music fast evolving out of its prog-rock beginnings. The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway had itself been a departure, a boundaries-redefining concept album recorded under highly strained circumstances. Eventually, Peter Gabriel — lead vocalist, focus of much of the on-stage theatrics and, in the eyes of most uninformed onlookers, the group’s leader — left.

And then there were four.

The band were keen to continue without Peter. The musical ideas flowed, but it was music in search of a vocalist, the story often told of how one replacement singer after the next was tested and rejected before drummer Phil Collins eventually stepped up.

Rather than the usual catch-all ‘Words and music by Genesis’ formula, songwriters were now individually credited for the first time. Tony Banks’s growing dominance is therefore evident to the reader as well as the listener. Two of the eight tracks on 1976’s A Trick of the Tail are Banks solo compositions, and he is credited as co-writer on all the others. Overall, the mood is undeniably softer, warmer and more FM-friendly — easier on the ear after the shock of The Lamb: the sharp edges we associate with Gabriel-era Genesis have been smoothed away.

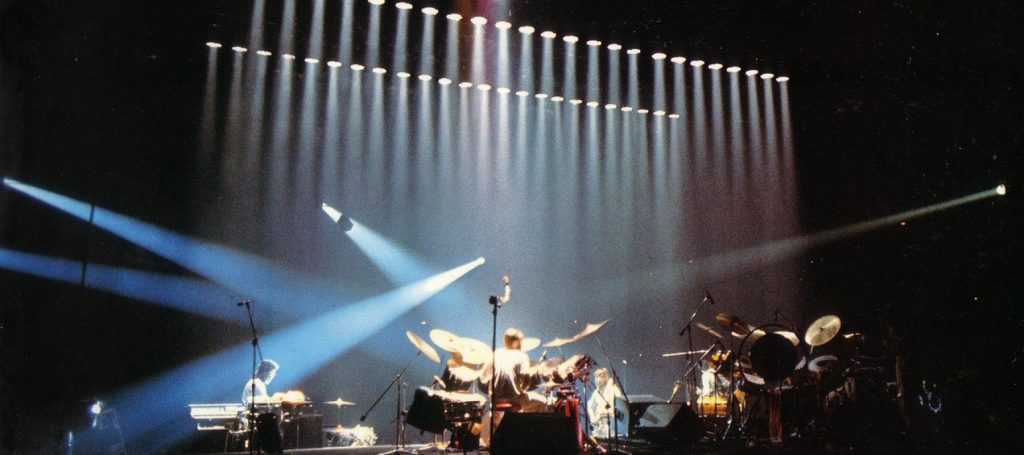

This bootleg, which sounds wonderful throughout, is from the Hammersmith Odeon in London on 10 June 1976. It is complete except for a couple of fade-ins between songs and is probably an official recording, as Phil announces to the audience that the show is being taped for release. It was recorded midway through a British and European tour, the second night of a run of shows at Hammersmith.

It wasn’t only the music for The Lamb that was wildly ambitious: the stage production featured elaborate costumes (for Peter at least), triple screens to project images illustrating the narrative, even a giant inflatable penis. On this tour, the staging is more conventional, though on a budget more suited to the larger venues they are now playing.

The setlist, like the band, has undergone something of a transformation:

Dance on a Volcano / The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway / Fly on a Windshield / Carpet Crawlers / The Cinema Show / Robbery, Assault and Battery /White Mountain / Firth of Fifth / Entangled / Squonk / Supper’s Ready / I Know What I Like / Los Endos / it. / Watcher of the Skies

Much of what is familiar to fans from the 1977 Seconds Out album, which omitted most of the Wind and Wuthering tracks played on that tour, is already in place. Indeed, the version of The Cinema Show included on side four of the original live album was actually recorded on this 1976 tour. Squonk is here too, placed midway in the set. Firth of Fifth has lost its piano introduction; I Know What I Like has found its tambourine solo. We are also introduced for the first time to Harry, anti-hero of Robbery, Assault and Battery, here preparing to “rob the Brentford Nylon Offices of their weekly takings”.

“Good evening, London! Great to be back,” announces the band’s new lead vocalist, Phil Collins, after the opening song. No explanations for Peter’s absence; no apologies, certainly. One of only two references to past Genesis history is a mention of the previous tour when they played the Lamb album in its entirety, Phil’s happy-go-lucky persona immediately asserting itself:

…tonight we’ve taken three pieces from the story — a bit here, a bit over there and a bit around here — put ‘em together and rather casually retitled it ‘Lamb Stew’.

Phil has huge shoes to fill, but he fits into them comfortably. The spotlight wasn’t a completely new experience for him: he had, of course, performed on stage from a young age. A tour of North America had also presumably ironed out a few front-man wrinkles. His voice is not yet as strong as it will become — he reaches the falsettos but struggles to find the necessary power at times, particularly on Entangled — but he is superb with the classic Gabriel-era songs and, despite disappearing behind the drum kit from time to time, never seems to miss a mark.

Gone, then, is the manic intensity of Peter and his ever more bizarre cast of characters. Gone, too, is a brooding presence stage right. Steve Hackett has grown — literally so, as he now stands throughout the show. His appearance, too, is visibly altering — no longer shielded behind the heavy-rimmed glasses, the thick, black beard and the dark clothes. The release of his debut solo album, Voyage of the Acolyte, was clearly about more than just the music.

He even gets to speak. Introducing Entangled as a song about a man who needs psychiatric help for a recurring nightmare, he responds to a playful shout of “Why?” from out in the audience with: “because he’s suffering from insomnia, that’s why, you idiot!” A more assertive Steve, indeed.

Unlike on Seconds Out — he left the band during the mixing process — Hackett’s guitar is delightfully prominent in the mix throughout this recording and is a joy to hear, not least during Carpet Crawlers and, of course, the epic Firth of Fifth. It must be said that Phil’s introduction of Steve as “the man they couldn’t gag, the Cambridge rapist” is jaw-droppingly inappropriate to modern sensibilities.

And then we are introduced to the new man at the back:

… our resident, temporary, permanent, stand-in drummer … the well-known misprint and typing error Mr Bill Bloomington … Straight £5 a night, he’s not bad, is he?

Bill Bruford is far from being an anonymous presence. To these untrained ears, the duets with Phil sound terrific, and he serves up a percussion masterclass, particularly on Supper’s Ready: indeed, during the latter stage of Willow Farm, Bruford seems determined to hit everything except for the empty milk bottles outside the stage door. However, he was apparently too much of a maverick for a band highly reliant on cues on stage, and he did not return for the Wind and Wuthering tour.

An unexpected delight on first hearing is the return of White Mountain to the set. Mike Rutherford takes us on a nostalgic journey back into Genesis’s past to when “the clinking of beer mugs could be heard very clearly” during songs from the Trespass album — “acoustic songs off the Trespass album”, he quickly clarifies, presumably after shouts for The Knife. Elsewhere, Steve informs us that the lyrics of Entangled are based on a painting by Kim Poor, who went on to design several of his solo album covers and who he later married.

Dance on a Volcano and Los Endos bookend the show, as they do on A Trick of the Tail. For fans growing up on Seconds Out, it’s odd to hear them separated out in this way — particularly the drawn-out introduction to Los Endos which was omitted on subsequent tours. The encore, familiar from the (UK version of the) Three Sides Live album, starts with the song it. from The Lamb before segueing into a shortened version of Watcher of the Skies. The same format — with two different songs — was used on the Wind and Wuthering tour.

Selling England by the Pound is probably (at least in this fan’s opinion) their best studio album, but the 1976–77 period — what we might refer to as ‘The Tony Banks Years’ — represents Genesis in their prime, particularly on stage. Their music, led by Tony’s keyboards, is ambitious yet accessible, Steve Hackett is still committed (it seems) to the band, and Phil Collins has successfully made the transition from drummer to front man, able to deliver Gabriel-era material as least as convincingly as Peter himself. Their stage lighting and production is also becoming vastly more ambitious. This bootleg, then, is an outstanding recording of Genesis at their peak.

Note: This Hammersmith 10 June bootleg is, to my knowledge, the best audio recording of a complete Genesis show from 1976. A 42-minute film of Genesis live in 1976 called Genesis: In Concert is now widely available, having been officially released as part of a reissues package for A Trick of the Tail. Sadly, it is heavily edited but features about 30 minutes’ worth of excellent footage shot elsewhere on the British tour. It sounds great too. As mentioned above, the version of The Cinema Show used on Seconds Out was from 1976, as was it. / Watcher of the Skies from the UK version of Three Sides Live. Entangled, recorded at Stafford Bingley Hall, appeared on the Archive 2: 1976–1992 collection.

Montreal 1974: Genesis Bootlegs

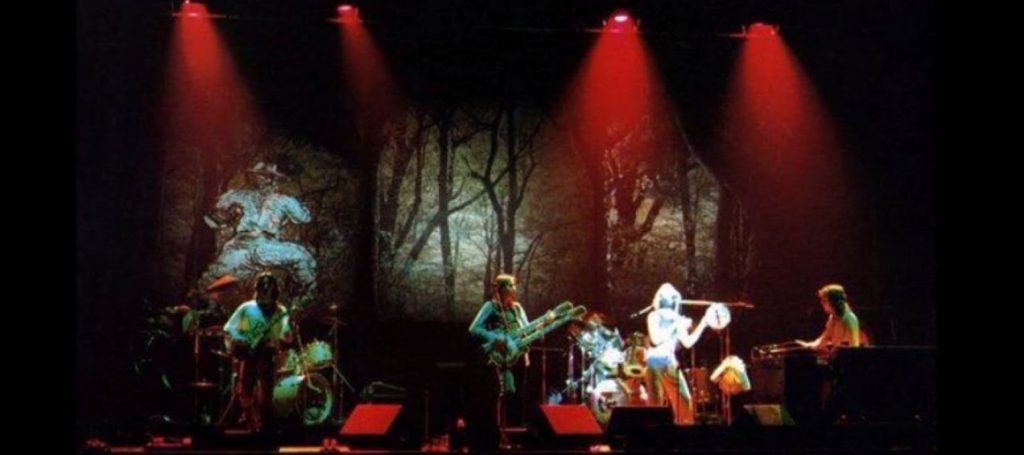

It is 1974. In Britain and parts of Europe, notably Italy — though not yet North America — Genesis have broken through to the big time: top-ten albums, decent-sized venues such as the London Rainbow, front-cover status in Melody Maker. This bootleg — an FM radio broadcast — captures the band in Montreal on 21 April. For many longtime fans, this is ‘classic’ Genesis: the Tony Banks / Phil Collins / Peter Gabriel / Steve Hackett / Mike Rutherford line-up. It is the era of the Mellotron and twelve-string guitars, of fox heads and old-man masks, of hermaphrodites and hogweed.

As on the previous tour, Watcher of the Skies opens proceedings — the eerie, doom-laden sound of the Mellotron familiar to fans from the Foxtrot and Genesis Live albums, a foretaste of the drama and (imagined) theatrics to come. Prog rock à la Genesis delights in long, complex pieces with repeated changes of mood and tempo. The set-list draws from three classic albums of the genre — Nursery Cryme, Foxtrot and the then-current Selling England by the Pound:

Watcher of the Skies / Dancing with the Moonlit Knight / The Cinema Show / I Know What I Like / Firth of Fifth / The Musical Box / Horizons / The Battle of Epping Forest / Supper’s Ready

The first ‘proper’ Genesis album, Trespass, is here unrepresented. The Knife, the standout Trespass track, was only very occasionally played on the tour as an encore, it seems. Indeed, on most nights they appear to have ditched an encore altogether.

Lacking the studio polish of the official releases to balance the sound and smooth away the rough edges, several passages here sound pleasingly urgent and aggressive, and it is interesting to compare the songs that also feature on the official Genesis Live album, released a year or so earlier. The bass (or bass pedal) during the Watcher of the Skies opening is more apparent, for example, adding to the sense of drama and foreboding, and during the heavier Musical Box sections it is as if Steve is battling to control his volume pedal.

This recording is by no means perfect — radio interference leaks into the sound during quieter passages — but one of the pleasures of bootlegs for fans is the chance to hear their favourite bands in the raw, as it were: the mistakes and mishaps on stage, the experiments that didn’t work and were subsequently dropped, the early performances of songs before further reworking.

Firth of Fifth is a case in point. An undoubted Genesis masterpiece, it is hard to believe (see the Chapter and Verse book) that it almost wasn’t recorded. Here it is played in full, complete with Tony’s opening solo, dropped for subsequent tours. Played on keyboard rather than grand piano, it lacks the majesty of the original recording — in other words, it’s easy to see why it was dropped in favour of the powerful “The path is clear…” opening. Steve’s playing also seems at times to be a little less fluent than on the later Seconds Out version, for example.

Other than the opening and closing drone sound, I Know What I Like is less drawn-out than in later years — and better for it. Bootlegs capture Peter weaving his elaborate between-song stories — here delivered in schoolboy-though-passable French to the Quebecois French-Canadian audience. They are also the only way — at the time of writing, at least — to hear live versions of The Battle of Epping Forest. Only Steve’s Horizons, played here on electric guitar, seems a little out of place. It appears to have been alternated on this tour with another slight song, More Feel Me, sung by Phil, which features on the Genesis Archive #1 release, recorded at the Rainbow in October ‘73.

Much of the sense of drama came from Peter’s on-stage antics, inevitably all but lost in audio-only recordings. To the already established costume-changes — bat wings, fox’s head and the rest — he has now added the character of Britannia, who introduces Dancing with the Moonlit Knight. Its closing section evokes a pastoral feel; Steve’s lilting guitar combines with the soft tones of the Mellotron, Peter’s flute, the sound of church bells ringing and even the call of the cuckoo.

It serves to further accentuate a strain of eccentric Englishness that lies at the heart of early Genesis, with lyrical themes and references ranging from King Canute and Kew Gardens to fox hunting and evocations of quiet country villages. The lyrics — and Peter’s vocal delivery more generally — are also a source of much of the quietly eccentric humour. As well as bringing to life a rich cast of characters, he has developed a number of peculiar vocal mannerisms, enunciating particular words and phrases in a singular style — “has life again destroyed life?” during Watcher of the Skies, to take one example. Elsewhere, with the band still not quite ready to begin after Peter’s ‘Britannia’ monologue setting up Dancing with the Moonlit Knight, he utters a single word — “Interlude” — as if he were part of a Monty Python continuity sketch.

This quaint and quirky and distinctly English sense of the absurd is further explored in I Know What I Like and The Battle of Epping Forest, each with its cast of characters, whose eccentricities are played out on stage by Peter. The latter, in particular, features whimsical wordplay — “a robbing hood”, “a karmamechanic with overall charms” — and there’s an amusingly down-to-earth little interchange involving Phil on backing vocals: “What’s the trouble, then?” It’s easy to picture Peter shuffling across the stage as the lecherous old man in The Musical Box, as he wheezes lines like “Brush back your hair and let me feel your flesh”.

The climax of the show is the epic Supper’s Ready, perhaps the quintessential prog-rock piece. The closing section of the song, As Sure as Eggs Is Eggs, is soaring, magnificent, glorious. Yet, watching the official Shepperton Studios live footage, shot the previous October, the song’s visual power comes principally from the use of simple fluorescent effects. Indeed, watching the film as a whole, the viewer is struck by its amateurish feel: the set is extremely basic, the lighting is poor and Peter’s costumes look home-made. The dramatic energy comes from the music and, in particular, from Peter’s extraordinary on-stage performance. In this sense, too, the ‘Selling England’ tour represents a crossroads for Genesis.

In a radical departure, the band played The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway in its entirety on the following tour, with only The Musical Box and sometimes Watcher of the Skies surviving as encores. Peter then left the band. This bootleg is valuable, therefore, in capturing the end of a Genesis era, with the band at their prog-rock peak. By 1976, they were back with Phil on vocals, a much more expensive and professional-looking stage show, much — though by no means all — of this classic material retired, and a warmer, less edgy sound.

Note: Officially released live recordings at the time of writing are the album Genesis Live and the Genesis Archive #1 box set recordings from the Rainbow (October 1973) and The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway. The official but as-yet-unreleased film of the band recorded at Shepperton Studios in late-October 1973 is widely available online, as is a longer version of the Genesis Live recordings, including more between-song audio and Supper’s Ready, and a longer version of the Rainbow show.

An Apostrophes Question

This blog goes through the basic rules about when and how to use apostrophes.

It gets lots of hits. My guess is that most visitors arrive here because they have googled something like Does x need an apostrophe? Perhaps that’s you.

If so, I hope it answers whatever question you have.

However, I originally wrote a lengthy post called An Apostrophes Question to try and answer a very specific query – namely, whether phrases like parents’ evening require an apostrophe.

If you do actually want to read more about phrases like parents’ evening and girls’ school and whether or not they need an apostrophe, I have moved the original post to here. I revised it in June 2022. I also highly recommend my style guide, which is free for you to read and/or download from here.

Apostrophes: the basics

We use apostrophes for two reasons:

- to indicate possession or belonging

- to indicate that words have been contracted (shortened)

Apostrophes are NOT needed for simple plurals (more than one of something). You see this mistake time and time again on shop signs and the like. It’s even got a name — the greengrocer’s apostrophe:

a bag of potatoe’s; fish and chip’s; open Monday’s to Saturday’s

Incorrect uses of the apostrophe. They are just simple plurals.

Using an apostrophe to indicate possession or belonging

We use the apostrophe to denote possession:

the musician’s guitar means ‘the guitar of/belonging to the musician’

the farmer’s tractor means ‘the tractor of/belonging to the farmer’

the team’s performance means ‘the performance of the team’

Note that it doesn’t have to be literal possession. It can just mean ‘of’ or ‘of the’.

the patient’s health problems

the light’s brilliance

Most nouns in the plural end in ‘s’ or ‘es’. In these cases the apostrophe comes after the ‘s’.

the musicians’ instruments means ‘the instruments of/belonging to the musicians’

the patients’ health problems means ‘the health problems of the patients’

the bosses’ pay rise means ‘the pay rise of the bosses’

Some plural nouns don’t end in ‘s’. In these cases we treat the apostrophe as we would with a singular noun.

the people’s voice means ‘the voice of the people’

the children’s laughter means ‘the laughter of the children’

If someone’s name ends in ‘s’, the convention is to treat it like a plural noun and put the apostrophe after the ‘s’ unless you would make an extra ‘ziz’ sound when saying it aloud. To keep things simple I tend to add the extra ‘s’ most of the time.

Jesus’s disciples

Dickens’s characters

Genesis’s albums

Say any of the above aloud and you should hear yourself saying ‘ziz’.

That’s it for the basics. Check out page 11 of my free-to-download style guide for slightly trickier examples.

Using a apostrophe to show that words have been contracted (shortened)

We use an apostrophe when we shorten words by missing out certain letters.

It’s is short for ‘It is’.

We’re is short for ‘We are’.

Don’t is short for ‘Do not’.

Can’t is short for ‘Cannot’.

This may cause a bit of confusion because sometimes we use words with the same spelling but without an apostrophe. For example, as well as it’s we have its. As well as we’re we have were. As well as you’re we have your. There is also a noun cant, which means ‘hypocritical and sanctimonious talk’ and has nothing to do with can’t.

It all depends on the sense in which you are using the word. If you’re shortening two words into one (like I just did then with you’re to mean ‘you are’), use an apostrophe.

It’s a brilliant book is short for ‘It is a brilliant book’.