Queen On Fire — Live at the Bowl: Reviewing the Review

Introduction

I was interested to see what, if anything, had changed — my knowledge of Queen, my thoughts and opinions, other contextual information — in the fifteen years since I wrote my review of the Queen On Fire – Live at the Bowl DVD. At the time, I titled the review ‘A Crown Jewel’ and awarded the DVD five stars out of five. It was published on Amazon in November 2004, a week or so after the DVD’s release.

As I write now (July 2019), the DVD is not available from the official online shop, though the audio is available for download. It was never officially released on Blu-ray.

The original review text is shown in italics.

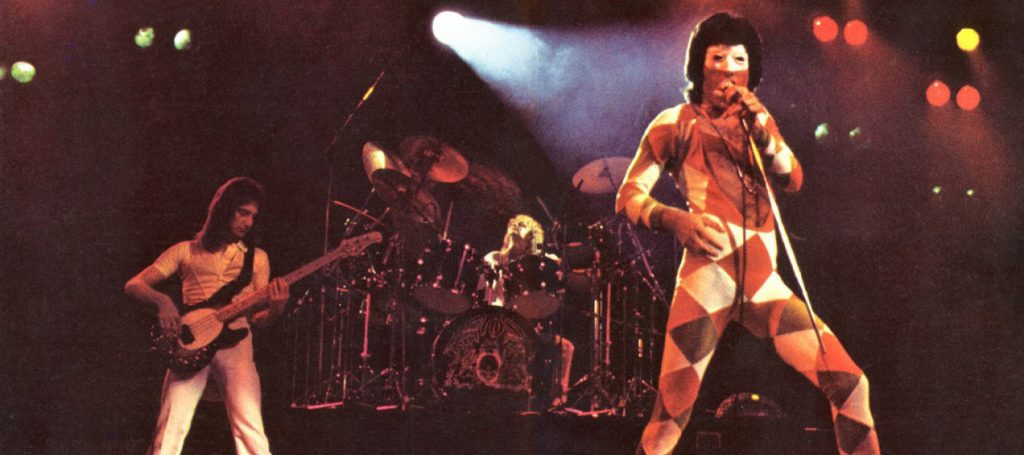

For Queen obsessives, the advent of remastered CD and DVD has served to keep the – ahem – ‘magic’ alive long after the demise of the band itself as a creative unit. The latest release is this long-awaited Milton Keynes Bowl concert, recorded June 1982, on the European leg of the Hot Space tour. A heavily-edited film of the show was first used, improbably enough, on Channel 4’s alternative music show The Tube in 1983; that edit has since featured regularly on VH1. Individual songs have also appeared in video montages and compilations. Now, after the success of the Live at Wembley Stadium DVD, this is the MK show in its entirety – warts ‘n’ all – and very welcome it is too.

The opening sentence was obviously written in the resigned belief that the days of Queen as a going concern were over. Though purists would doubtless question the whole notion that Queen are again a creative unit, the ‘Queen’ brand is certainly very much alive and kicking. The beginnings of the Queen/Paul Rodgers collaboration were in 2004, leading to major tours in 2005 and 2008 and to the The Cosmos Rocks album. Even more successful has been the Queen/Adam Lambert collaboration. That’s not to mention the longevity of the We Will Rock You stage musical and the phenomenal success of the Bohemian Rhapsody film.

Alas, contrary to my remark in the last sentence, not quite every wart was in fact included in the DVD. Check out the clip below [at roughly 2:22] which was left in the original Channel 4 broadcast but polished out of the Live at the Bowl release.

Previous ‘live’ offerings from Queen too often suffered from heavy handed editing, remixing and general interference, sometimes due to the limitations of technology at the time but more often in a mistaken attempt at quality assurance. The nadir is 1986’s Live Magic which employs a ghastly mixture of omission and (unbelievably) song editing to fit a two-hour show onto LP. A close second is the video of 1985’s Rock in Rio triumph: Brian May’s guitar is hopelessly buried in the mix and the overall band sound is dull and blunted. Now, as this DVD demonstrates, even on basic home equipment, digital remastering brings a raw freshness to the sound as well as sharpness and colour to the picture.

I think this paragraph generally holds true, though whether the freshness and sharpness I applauded at the time is simply the result of digital mastering I now realise I am not expert enough to say. I have written elsewhere about the failure of official releases to capture and authentically convey the live Queen sound. The release of the Live at the Rainbow ’74 box set in 2014 set a new benchmark. Despite the “limitations of technology at the time” [my words], both of the 1974 concerts sound superb, particularly the 31 March gig. I still regard the Procession/Father to Son opening as probably the most powerful beginning to a live album that I am aware of, though to be fair the Milton Keynes opener (Flash/The Hero) is great too.

After the pomp and grandeur of two world tours between 1977 and 1979, their stage show by 1982 had adopted a pared-down, ‘hot and spacey’ feel to match their changing musical direction. The grandiose ‘Crown’ lighting rig in 1977-78 and the ‘Pizza Oven’ roof of lights that spectacularly adorns the Live Killers sleeve were replaced by relatively modest, moving banks of lights and powerful spots. Musically, while the new songs from the sharply criticised Hot Space album undoubtedly benefit from a live work-out, this viewer well remembers their muted greeting by the crowd at the previous week’s Elland Road concert.

Absolutely. Back Chat and Staying Power both sound superb. It baffles me why one of these two songs was not released as the lead-off single for the Hot Space album. For the subsequent US and Japanese tours, other Hot Space tracks were given a workout, notably Put Out the Fire and Calling All Girls. Even Body Language didn’t sound completely awful played live. As it happens, I have recently been listening to Genesis bootlegs from roughly the same period: the muted crowd reaction to the newer Abacab material is similar to what I describe here. It was a tough time to be a fan of ’70s rock giants!

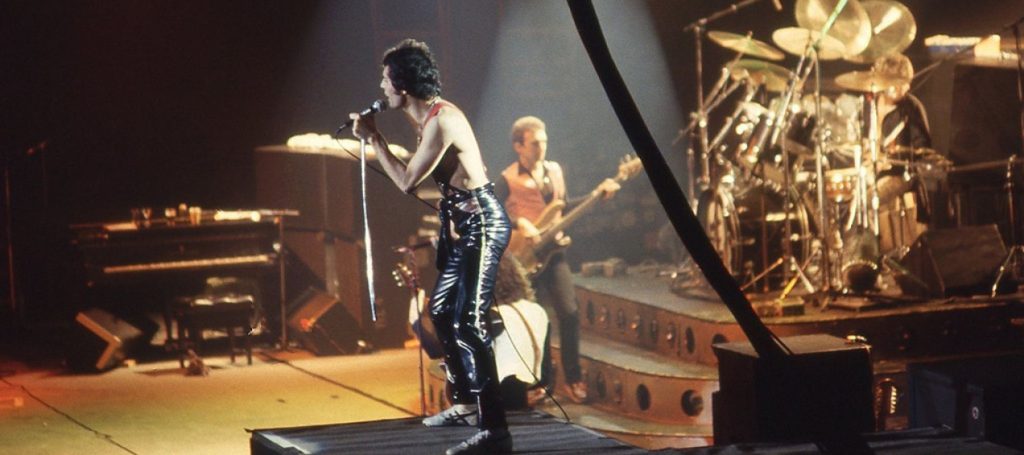

However, Queen always delivered onstage and this DVD magnificently captures the power of Queen live. Freddie is in particularly mischievous form, teasing and energising the crowd (“are you ready…are you ready brothers and sisters?”). The consummate showman bounds across the stage and athletically utilises gangways incorporated into the stage set to project the band in larger venues. Though Freddie did not personally write a Queen blockbuster after 1979’s Crazy Little Thing Called Love, he was still fit and lithe, aged 35 in 1982, the singing voice strong and assured. Only later did a combination of wear and tear, age and smoking lead to difficulties at the end of long shows and tours. Before AIDS (first identified in 1983), it is also interesting to note the overtly sexual nature of much of his onstage banter, strutting and posing.

The obvious error in the above paragraph is the one relating to Freddie’s voice. When I wrote those words, I hadn’t really heard many bootlegs of Queen shows, so I only had official releases and what I remember actually hearing live to go on — neither of which is (sad to say) a reliable guide. Having listened to a lot of bootlegs since 2004, I now realise how inaccurate the statement is. In reality, from the later-1970s at the very latest, Freddie was regularly struggling with his voice on stage, especially towards the end of long tours and particularly towards the end of shows.

Japan definitely got the shortest of short straws in this respect – unfortunate, as they were particularly keen to film the band’s concerts. With the exception of the February ’81 Budokan shows, all of the band’s tours to Japan followed on from extensive touring in other parts of the world. Listen, to take just one example, to how Freddie struggles to sing Bohemian Rhapsody during the 1979 Japanese dates. You can point to lots of similar examples from the ’82 and ’85 tours. We Are the Champions always presented problems — Roger to the rescue! — as did (from 1984 onwards) Radio Ga Ga.

Now think about the official releases. Montreal ’81 — voice superb — came after a month-long break. Milton Keynes ’82 — voice superb — came after a three-day break on a mini-British tour of just four shows. Live Aid too — voice superb — came after a very lengthy break. Hammersmith ’79 — not an official release (yet, but we live in hope!) but generally acknowledged to be a superb vocal performance — came after a four-day break (and Christmas dinner).

Jumping ahead to Wembley ’86, there were relatively long breaks between most shows on the Magic Tour. But Freddie was older, the stage was enormous and the filmed Saturday show followed on from the additional Friday concert. It’s not too bad vocally, but there’s lots of stuff sung in — what is it called? — the lower register, masked by the impressive-sounding cod-operatic delivery. True, Budapest was a stronger vocal performance than Wembley, but it came on the back of a five-day break.

The performance – and the filming – is not quite as polished as 1986 and casual buyers might begin their collection with the aforementioned Live at Wembley Stadium DVD. It was 1985’s Live Aid that truly elevated Queen to superstar status. In 1982, the set list still contained obligatory new-album material and hard-rocking (but relatively uncommercial) stage favourites like We Will Rock You (fast) and Sheer Heart Attack. For the Queen connoisseur, however, there is much to enjoy. Particular highlights include Somebody to Love: a singalong favourite and live staple from 1976, it was inexplicably left off the Live Killers LP and finally dropped in 1986. If Queen’s finest hour (or, rather, 17 minutes) at Live Aid can be criticised, it is surely the inclusion of Hammer to Fall at the expense of Somebody to Love.

Absolutely. The whole show sounds great, and the performance of Somebody to Love is indeed a highlight, as is The Hero opening, Fat Bottomed Girls — “You made an asshole outta me!” — and Save Me, to choose just three. I also still think I am correct about the Live Aid set.

One criticism I don’t mention is that the final twenty minutes or so feel a touch predictable. Once Freddie plays the opening bars of Bohemian Rhapsody, you can guess how things are going to pan out. The close of the show could have done with some refreshing by this point, I think. After all, albeit with some moving things around on occasion (and the introduction along the way of Another One Bites the Dust), Tie Your Mother Down / Sheer Heart Attack / We Will Rock You / We Are the Champions had been the basis of the latter part of the show since late-1977.

We now know that earlier in the Hot Space tour they appear to have mixed things up a bit — Tie Your Mother Down and Sheer Heart Attack were both tried out at the beginning of the set after The Hero, for example, and Liar was even played in its entirety on a couple of occasions — but by the time of the British shows they had reverted to the ‘usual’ ending. It’s just a thought, but one wonders whether they were nervous at the reaction to their new material and tacking to safer waters.

Another fine Milton Keynes moment is the gloriously un-PC Fat Bottomed Girls. Unfortunately, a raucously out-of-tune scream by Freddie has been polished out – but at least problems with Brian May’s lead during his earlier solo spot have been left in; anoraks truly treasure such moments! This tour is also noteworthy for fans as the first to feature additional (off-stage) keyboards to supplement the band’s sound. Brian’s ‘chat’ before Love of My Life is also somewhat unusual. Dedicating the song to people “who have given up their lives for what they believe”, it is a reference to the Falklands War that dominated the headlines that spring and summer: Queen were in an acutely difficult position as they had played in Argentina the previous year, were selling phenomenally well over there and had just released a single in English and Spanish – Las Palabras de Amor.

Overall, Live At Milton Keynes Bowl is another top quality Queen DVD. What delights await next Christmas? Paris 1979? Houston or Earl’s Court 1977? Hyde Park 1976, please.

As it happens, none of the above suggestions have yet seen the official light of day in full. Oddly enough, I didn’t mention Hammersmith 1979. I had high hopes that footage from 1979 might be released this year — there is plenty of it — to tie in with the fortieth anniversary of the release of Live Killers. Alas, nothing has appeared as yet.

Footage of Sweet Lady from Hyde Park has appeared as a DVD extra, and some of the Houston footage was used in the Old Grey Whistle Test documentary released in 2017. My Melancholy Blues and We Will Rock You (fast) from the same gig have also appeared officially, as have Fat Bottomed Girls and Sheer Heart Attack from Paris.

I neglected in the original review to mention the bonus material in the original review. It’s decidely patchy. There are some tour interviews, a photo gallery backed with a live version of Calling All Girls, some backstage Milton Keynes material, and some footage from Austria earlier in the tour. The highlight is about thirty minutes’ worth of footage from Japan from November 1982, the very final show of the world tour. It has long been available as a Japan-only VHS release. As suggested above, with Freddie’s voice cracking in places, the show is unlikely ever to be given a full release.

Seconds Out — The Greatest Live Album?

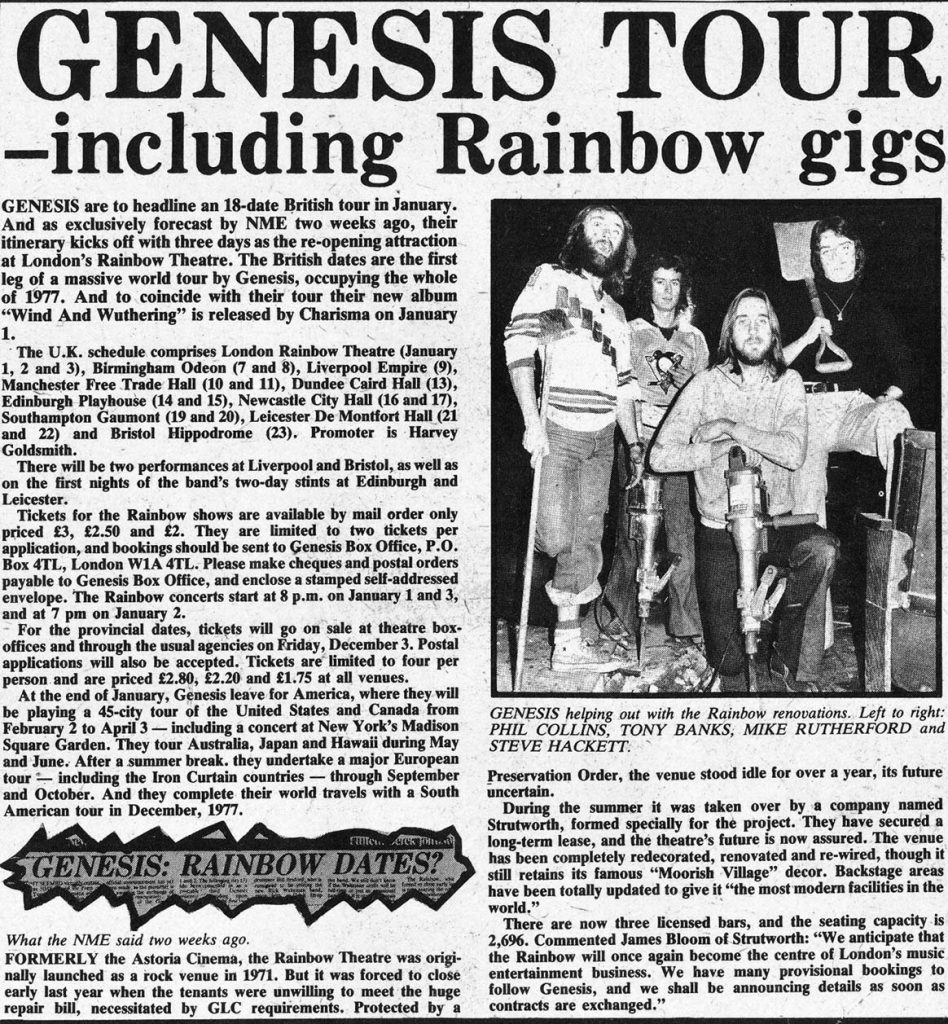

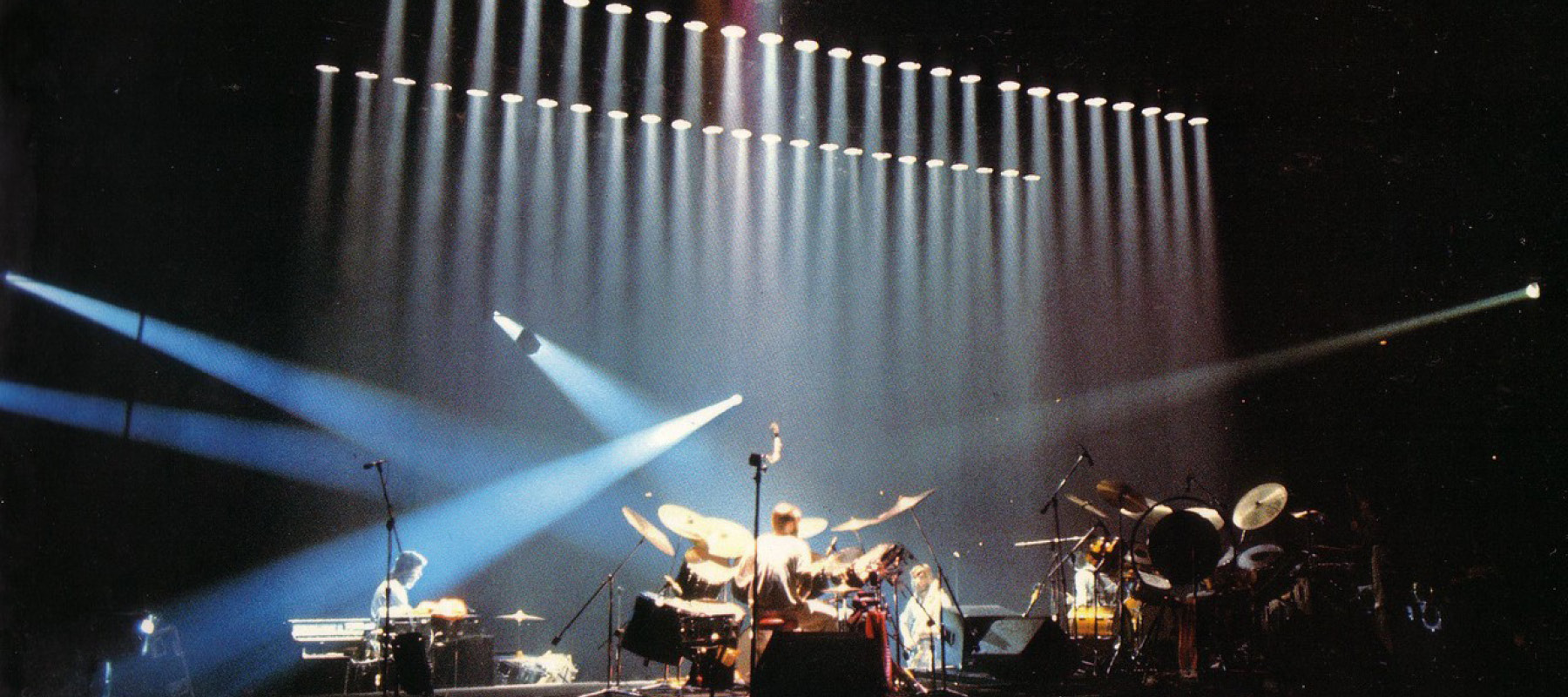

Reflections on Seconds Out and Genesis live on the 1977 Wind and Wuthering tour

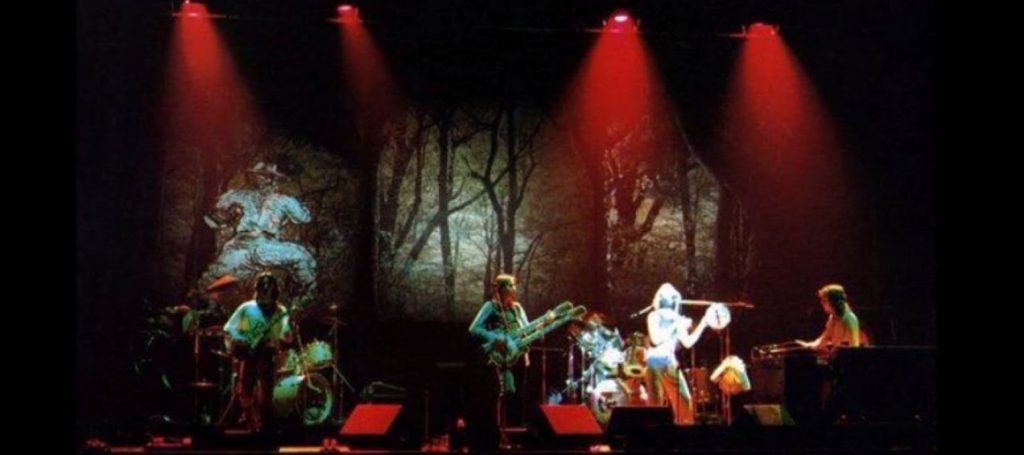

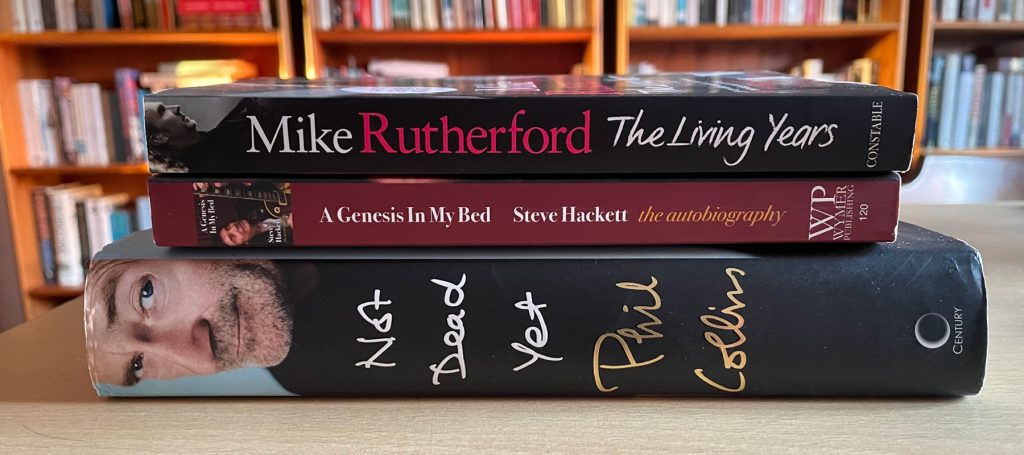

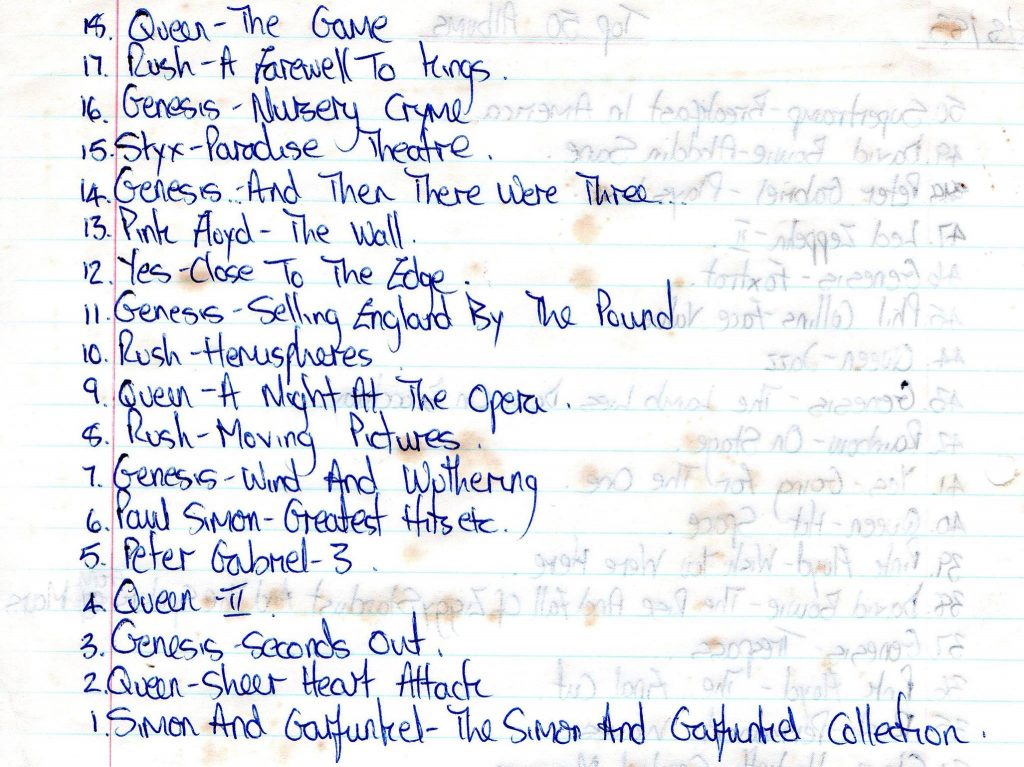

I probably bought Seconds Out in 1979 aged twelve or thirteen, having discovered the band via And Then There Were Three. As luck would have it, my local library stocked Armando Gallo’s lavishly illustrated book I Know What I Like so I soon had a good sense of how Seconds Out fitted into the Genesis story. Recorded in Paris in June 1977 towards the end of six months on the road promoting the Wind and Wuthering album, it captures ‘old’ Genesis and features almost the very last performances of the four-plus-one line-up: Steve Hackett’s absence from mixing-desk duties over the summer effectively signalled his departure from the band. If memory serves, Gallo refers in his book to this being his favourite tour, the band, he says, performing almost flawlessly night after night.

The original October 1977 release featured twelve tracks spread across four sides of vinyl:

Side 1: Squonk / Carpet Crawlers / Robbery, Assault and Battery / Afterglow

Side 2: Firth of Fifth / I Know What I Like / The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway / The Musical Box (excerpt)

Side 3: Supper’s Ready

Side 4: The Cinema Show / Dance on a Volcano / Los Endos

With Peter Gabriel’s departure in 1975, the harshness and aggression noticeable in their earlier material — the likes of The Return of the Giant Hogweed — has given way to a softer and more polished sound. In part, this comes from Phil Collins – his vocal more soothing and melodic than Peter’s husky voice. Tony Banks, meanwhile, is the dominant musical presence, his lush keyboard sound leading the way in song after song and smoothing away the rough edges of the original recordings. With Steve Hackett’s guitar often an elusive, spectral presence floating free in the air, it falls to Mike Rutherford’s bass to provide counterpoint to Tony, such as during the exquisite keyboard solo starting at roughly 2:25 of Robbery, Assault and Battery.

Carpet Crawlers — an unlikely staple of the live show over the years — builds gently but insistently from its delicate opening. Robbery, Assault and Battery bounces with cockney swagger, allowing Phil to dust off his boyhood Artful Dodger character. The Dance on a Volcano / Los Endos medley closes the main set in thrilling fashion, as the 747 landing lights and dry ice depicted in the spectacular front-cover photo bathe the stage in ghostly white.

It gets better. Ahead of us lie perhaps the four finest Genesis moments on record.

A Genesis diehard will more than likely argue that Supper’s Ready, which dominates the third quarter of the set, is the band’s signature song – their Stairway to Heaven, their Smoke on the Water. It is epic, ambitious, daring — and on Seconds Out it is magnificent. The delightful sound mix helps, of course, but so does Phil’s front-man masterclass — by turns quirky and playful, soaring and majestic — offering his own interpretation of the song and more than doing justice to Peter’s original vocal.

The finale, As Sure as Eggs Is Eggs, is heady stuff indeed:

The lord of lords

Supper’s Ready

King of kings

Has returned to lead his children home

To take them to the New Jerusalem

Turn it up to 11, sit back and try not to shed a tear or two.

Two songs from arguably their best album — Selling England by the Pound — are a particular joy. The Cinema Show is a patchwork quilt of musical ideas — a succession of miniature keyboard flourishes and dazzling drum fills from the Bruford–Collins combination at the back, building to a show-stopping bass run from Mike at approximately 9:52. Though it is primarily a Tony Banks song, Firth of Fifth is Steve’s moment in the limelight. Often a peripheral presence, here is a chance for guitar to take centre stage.

And then there is Afterglow — an as-good-as-it-gets, goosebumps Genesis moment.

Now I’ve lost everything I give to you my soul

Afterglow

The meaning of all that I believed before escapes me in this world of none

I miss you more

Written in minutes (says Tony) and set lyrically in the immediate aftermath of some cataclysm or other, it builds from a hypnotic guitar riff to a spine-tingling climax, complete with angelic choir1, an effect he uses elsewhere on the album with equally dramatic results.

Ironically, Squonk is, for this fan at least, one of the weaker tracks – ironic in the sense that, for obvious reasons, the set opener is usually exceptionally strong. I Know What I Like, their first hit single, is also a dip of sorts. Performed live, it stretches out over eight minutes and more, a space for Phil’s on-stage antics with a tambourine. It’s an interlude of musical light relief, though the improvised middle section drags somewhat.

Everything I thought I knew about Genesis live in the seventies came from three sources: the Gabriel-era Genesis Live album, Gallo’s book and Seconds Out. Times change. Today the Genesis fan has an abundance of source material – the lengthy interviews making up the official Chapter and Verse book, for example, are a mine of useful detail, anecdote and context.

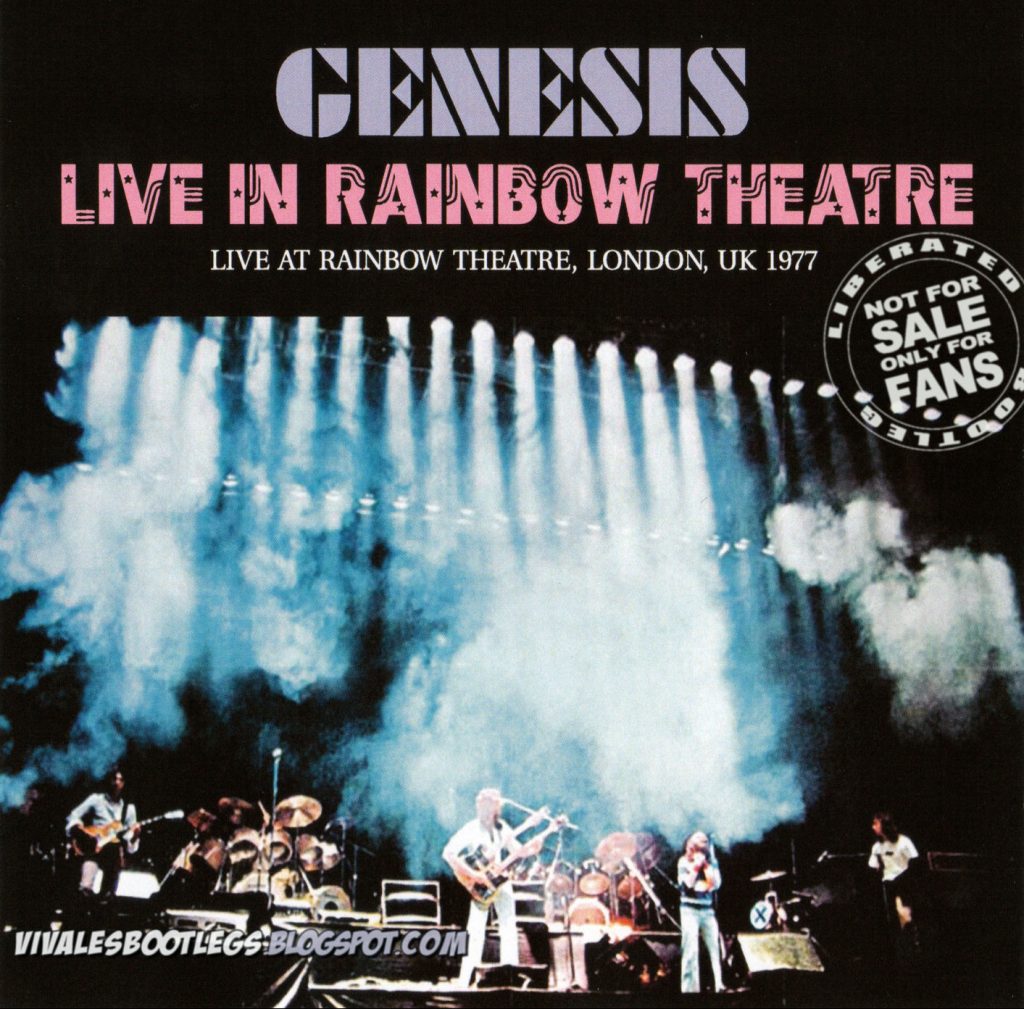

Armando Gallo had privileged behind-the-scenes access, but we can all now follow in his footsteps and check out the tour at various stops along the way. These reflections are based on seven excellent bootlegs from the Wind and Wuthering tour, all readily available for download completely free of charge: the London Rainbow and Southampton (January), Dallas and San Francisco (March), Sao Paolo (May), Earls Court, London (June) and Zurich (July). Listening to them offers us a far more complete picture of Genesis live in 1977 than the one presented by Seconds Out.

The actual running-order of the live show varied considerably from the Seconds Out track-listing. After some experimentation during the initial British dates (including, it seems, the short-lived inclusion of Lilywhite Lilith and Wot Gorilla), the set list eventually settled down to this:

Squonk /

Songs that were played live but don’t appear on Seconds Out are shown struck throughOne for the Vine/ Robbery, Assault and Battery /Your Own Special Way/ Firth of Fifth / Carpet Crawlers /In That Quiet Earth/ Afterglow /Eleventh Earl of Mar/ Supper’s Ready / Dance on a Volcano / Los Endos / The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway / The Musical Box (excerpt)

Eleventh Earl of Mar occasionally opened the set, and The Knife was included as an additional encore towards the very end of the tour, featuring on the Earls Court bootleg. All in a Mouse’s Night was played in the first few shows and then dropped relatively quickly for no obvious reason. Your Own Special Way was probably included as the then-current single. On stage, it falls rather flat despite some gorgeous additional piano from Tony. With the release of the Spot the Pigeon EP later in the year, the lesser-known but excellent b-side Inside and Out, another showcase for Steve’s guitar, took its place.

The Cinema Show was recorded on the band’s previous tour, having been dropped from the set by 1977. The reason for its inclusion here is not immediately obvious — a courtesy to Bill Bruford, perhaps (the band’s first fill-in drummer on stage: Chester Thompson took over drumming duties for the Wind and Wuthering tour and features on the rest of the album), or a discreet admission that leaving it out of the set had been an error (it was back for the next tour).

The decision to include The Cinema Show on Seconds Out and to omit several songs from Wind and Wuthering has a significant impact on the overall musical balance of the album. Unlike the live show, it is dominated by Gabriel-era music — in total, something like two-thirds, including the entirety of sides two and three — whereas at Dallas on 19 March, to choose one gig at random, Gabriel-era music comprises less than half the set. Five songs from Wind and Wuthering are performed (it was six in the early shows when All in a Mouse’s Night was played), of which only Afterglow eventually made it onto Seconds Out.

The words ‘supper’s ready’ are spoken by Phil to introduce, well, Supper’s Ready. They are the only words spoken on the album (except for a brief, breathless “merci, Paris” and “merci, bonsoir”). It is all deeply serious. Except, in reality, it wasn’t. Seconds Out omits all the between-song chatter — and there’s a lot of it — and with it much of the humour that was integral to a Genesis show.

Phil is at the centre of it all, naturally. He’s following a tradition started by Peter, filling space to allow time for retuning and assorted tweaking and twiddling. So we miss out on the dodgy exploits of Harry the bank robber and the saucy goings-on of two virgins, Romeo and Juliet, the detail more or less titillating from one night to the next, presumably depending on whether the show was being broadcast live on radio. Mike joins in the fun. Your Own Special Way — about “Myrtle the Mermaid” — is apparently “racing up the Venezualan charts”. The story of Eleventh Earl of Mar, meanwhile, is set in Scotland, “a small country just north of England”. This levity is all perhaps a bit too much for Steve, who politely informs the audience that Firth of Fifth is “a song about a river”.

When the audience heard Phil announce at, say, Southampton Gaumont Theatre on 20 January 1977 that “this next one is from our new record”, did they already have an inkling that what they were hearing was one of a collection of songs that would stand the test of time — songs that are as fresh and exhilarating to hear in 2019 as they were when first released over forty years earlier?

Bootlegs offer us a more rounded picture than official releases — rough edges and raw mixes, mistakes and miscues — and as such they are essential listening for any fan. But Seconds Out provides something more. Beautifully mixed (to this amateur’s ears, at least), it captures a band at the peak of their game, playing many of their finest songs and sounding exquisite throughout. It is a classic album – classic in the sense of ‘the best, the highest quality’, but classic also in its timelessness. It deserves a place on the shortest of shortlists of the greatest live albums of all time.

Notes

Hercule Poirot’s First Case

The Mysterious Affair at Styles by Agatha Christie (1920)

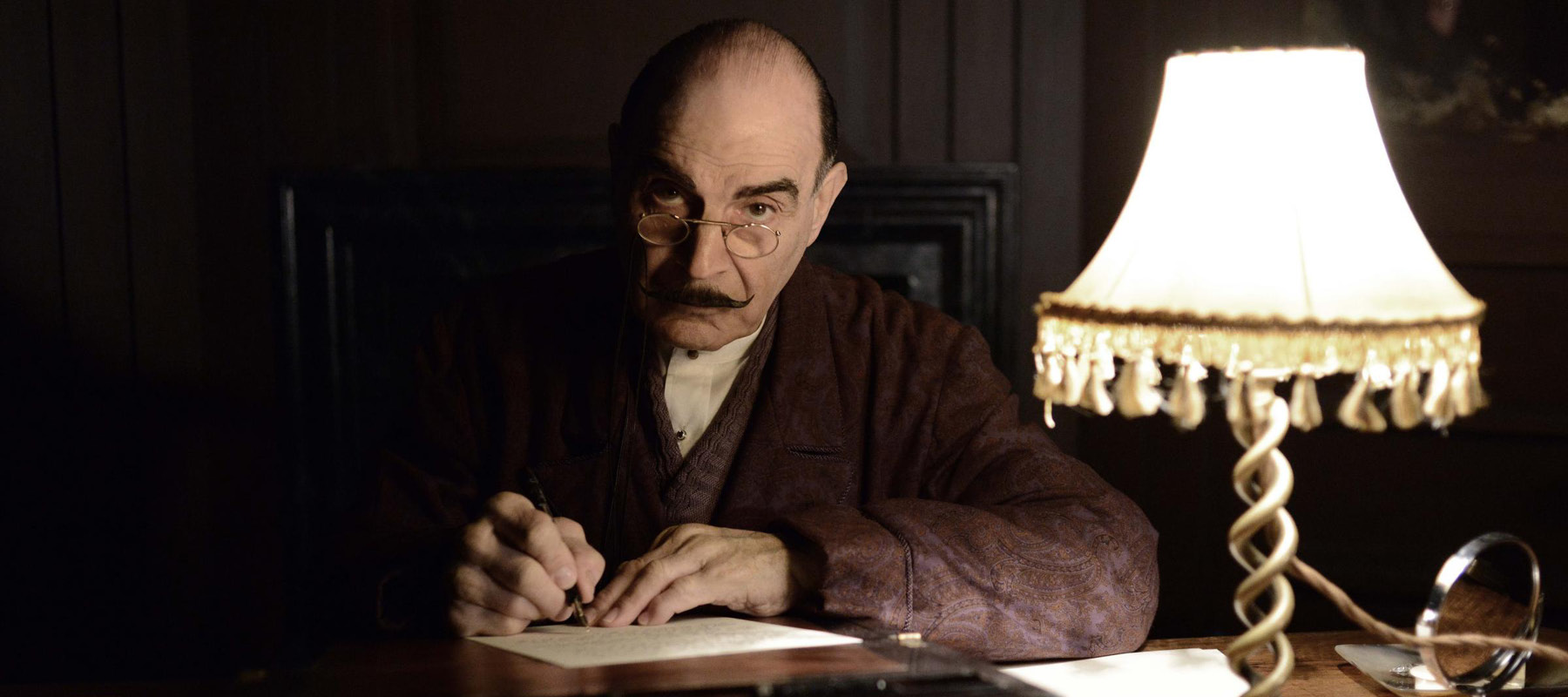

After revisiting the very final David Suchet TV adaptations on ITV3 fairly recently, I chanced upon a four-novel Poirot omnibus — actually two omnibuses, eight novels in total — in a local charity shop. Serendipity. Time to acquaint myself for the first time with Poirot in print.

Though a random selection — the novels are not sequential and, beyond the obvious, there is no linking theme — one omnibus did at least begin with The Mysterious Affair at Styles, the very first book of the Poirot series. That matters — a lot. A desire for completeness, perhaps. Begin at the beginning: Book One, Volume I, Series One, Episode One. It feels rude not to.

First, a little background. The detective novel was already an established and lucrative publishing phenomenon by the end of the nineteenth century. Edgar Allen Poe and Wilkie Collins are sometimes cited as pioneers of the genre — Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue was published in 1841 and Collins’s The Moonstone in 1868 — and characters such as Sherlock Holmes, Raffles and Father Brown were familiar to readers by the time Poirot first appeared in 1920. As literacy rates soared, the detective novel fed a growing popular appetite for sensational, lightweight (in more than one sense) reading.

The historian AJP Taylor described Agatha Christie, who was writing mainly in the so-called ‘golden age’ of detective fiction between the wars, as “the acknowledged queen in this art”. Having sampled so little of Christie’s writing (though plenty of film and television adaptations of her work), it seems prudent to heed the wise counsel of the incomparable Sherlock Holmes, who famously cautioned against rushing to judgement:

“It is a capital mistake to theorize before you have all the evidence. It biases the judgement.”

Sherlock Holmes in A Study in Scarlet (1887)

I will therefore go no further than the tentative but tame and unsurprising observation that The Mysterious Affair at Styles seems entirely typical of the genre at that time: the country-house setting; the simmering family tensions and jealousies, with legacy disputes the default motive for murder; the long list of likely suspects. Christie’s directness and economy of style are remarkable, a counterblast, perhaps, to the weighty, sprawling novels so typical of the nineteenth century — Dickens, Elliot, Hugo. Indeed, the entire Styles novel took just six hours to read.

There is little attempt at literary craftmanship — no descriptive digressions immersing the reader in location and atmosphere, no cleverly interwoven sub-plots or carefully constructed layers of meaning. The murder plot is (almost) all. Detail is provided insofar as it serves the needs of the plot, principally to widen the net of suspicion and usually to misdirect the reader — all the better to build suspense before the Big Reveal. Equally striking (to this reader, at least) is the poverty of language employed by Christie: I lost count of the number of times, for example, she refers to Hastings’s “lively curiosity”.

Consider the opening chapter, ‘I Go to Styles’ — the ‘I’ being Captain Hastings, who, like Holmes’s Watson, is our narrator and a casualty of war. In ten whirlwind pages, we are introduced to the Cavendish family, family friend Evie, and Cynthia, a foster child of sorts. Though the murder is yet to occur, the soon-to-be victim is obvious, as are at least three likely suspects: the husband, the brooding, troubled brother and a “sinister” (Hastings’s word) doctor, who happens (luckily for us) to be an expert in poisons. Indeed. the efficacy of poison as a modus operandi for dispatching someone is matter-of-factly discussed over afternoon tea. Poirot’s little grey cells will not be required to work out how the murder was committed.

Styles is a world apart: it is a gentrified world of privilege and entitlement, of property and inherited wealth, of starched-collar formality and strict etiquette. Women are referred to throughout as ‘Mrs’ or ‘Miss’. John Cavendish refers to his mother not as ‘mother’, ‘mum’ or even ‘mummy’ — but as ‘mater’. Endless summer days are spent lounging around the pool, playing tennis or going for long walks.

The landscape is sketched from the pages of William Blake. The industrial revolution, the most tumultuous and transformative event in our history, has by-passed this particular corner of England’s green and pleasant land. There is little or no factory-based work, no pollution, no cramped, stifling urban life. The few labourers we encounter are rough and ready but nonetheless deferential to their social superiors, like the gardener who doffs his cap on entering the boudoir. The servants, respectful and loyal, know their place and freely accept this ‘natural’ order of things, though (helpfully) they do like to listen at doors as their masters and mistresses bicker.

Set (and in fact written) during the First World War, the novel describes a world on which the sun was slowly setting, of course. Despite the trappings of privilege, the younger women are gainfully employed in war-related work: John’s wife works as a farmhand and Cynthia is a VAD, working in a dispensary — perfect for the poisonous plot! These details — and Hastings’s convalescence — notwithstanding, the war screams its absence. Like industrialisation, even total war cannot sully this pastoral idyll. The faithful parlourmaid Dorcas, described by Hastings as “a fine specimen … of the old-fashioned servant that is so fast dying out”, bemoans at one point the presence of a female gardener wearing breeches — surely the end of civilisation as we know it.

Novels are invaluable as windows into the attitudes, values and social mores of the time — and into peculiarities of speech and language. People ‘ejaculate’ and have ‘a queer way’. Cheerful people are ‘gay’. Women are ‘handsome’. Unpleasant men are ‘bounders’ and ‘rascally’. Bad things are ‘damnable’.

Less quaint is the unmistakeable whiff of casual racism and xenophobia. At least one of the comic-book suspects will invariably be sinister, somehow foreign-looking and ‘alien’ – a word that Hastings actually uses. Inglethorp, the main suspect, has an enormous black beard. Dr Bauerstein, an expert in poisons, is “a Polish Jew”. The supposedly sluttish temptress Mrs Raikes is a “gipsy” girl. It is worth noting that the 1990 television adaptation omits Dr Bauerstein completely, and Mrs Raikes becomes merely a farmer’s wife.

An obsession with race was central to Nazi ideology, ending in the gas chambers of Auschwitz. Less well known, perhaps, is the fact that concerns about the mental and physical health of the population also preoccupied inter-war Britain. The question of how to improve the racial ‘stock’ was not confined to the outer fringes of political debate; genetics, eugenics, sterilization and birth control were high up the agenda. Indeed, the historian Richard Overy has written:

“…the high point of the British eugenics movement, and of eugenics internationally, came in the years between the two world wars.”

Richard Overy, The Morbid Age

In a society rigidly defined by class, social snobbery is not hard to uncover, but the language of everyday discourse often betrays this wider obsession with racial hygiene and race improvement. For example, the overwhelming importance of maintaining the proverbial stiff upper lip even in the face of calamity — the death of Mrs Inglethorp — is expressed thus:

“Decorum and good breeding naturally enjoined that our demeanour should be much as usual…”

Captain Hastings, Chapter V

An absence of backbone, on the other hand, merits Hastings’s disdain:

“Never, I thought, had his indecision of character been more apparent.”

Captain Hastings, Chapter III

Lest we think this is merely the sneering of a snobbish Hastings, consider Poirot’s comment on an argument involving Lucy Cavendish:

“It was an astonishing thing for a woman of her breeding to do.”

Hercule Poirot, Chapter V

Later, reflecting upon the actions of Evie Howard, he comments thus:

“There is nothing weak-minded or degenerate about Miss Howard. She is an excellent specimen of well balanced English beef and brawn. She is sanity itself.”

Hercule Poirot, Chapter VIII

The cast of supporting characters are mere cardboard cut-outs; only the two principals — Hastings and Poirot himself — are given space to breathe and come alive. His friends might well have described Hastings as a ‘good sort’ — loyal, trustworthy and thoroughly decent. A true Englishman, they would doubtless have said. Confronted with a damsel in distress — a woman he has in fact known for barely a day — he impulsively proposes marriage. Like Nigel Bruce’s Watson, he is rather credulous and dim-witted. Fancying himself as something of a private detective, he is initially dismissive of Poirot’s thought-processes and obscure lines of questioning. Similar to the Holmes-Watson relationship, ‘the master’ sometimes treats ‘the assistant’ rudely, dismissively and thoughtlessly, only to offer profuse apologies later.

“We must be so intelligent that he does not suspect us of being intelligent at all … There, mon ami, you will be of great assistance to me.”

Poirot to Hastings, Chapter VIII

Hastings interprets this remark as a compliment, a recognition of his “true worth”. As with the earlier Holmes stories, the assistant-as-narrator device allows the novelist to engage in obfuscation and misdirection, withholding reveals in order to build mystery and suspense.

And what of Poirot himself? A Belgian refugee from his war-torn homeland, he is conveniently living with other compatriots in the village that Hastings (who knew him before the war) happens to be visiting. He is meticulous and particular, to be sure, but perhaps not yet quite the fully drawn dandy portrayed by Suchet, Ustinov and Finney, and certainly not the athletic swashbuckler depicted in Kenneth Branagh’s recent film. Of the John Malkovitch portrayal, I offer no comment.

Holmes felt so strongly about the dangers of leaping to judgement that he later reiterated the point almost word for word:

“It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.”

Sherlock Holmes in A Scandal in Bohemia (1892)

So my quest to uncover the original Poirot will go on. The omnibuses contain several other novels in addition to this first adventure. A reservation on the Orient Express awaits, as does an evening of bridge (Cards on the Table) and a visit to End House to confront the peril that lies therein. John Buchan’s thirty-nine steps are also yet to be climbed, and, going further back in time, the multi-layered, Benedictine world of Umberto Eco is long overdue a revisit. Yet the lure of Baker Street — the pipe, the violin, Mrs Hudson’s cooking — is impossible to ignore for long. The game is afoot.

Enlightenment Now: Book Review

We live in dark times. The forces of irrationalism and anti-progressivism are on the rise across the world – fascism, populism, nativism, authoritarianism, racism, religious fundamentalism. Enlightenment Now is thus a profoundly welcome book, a worldview diametrically opposed to that offered by populists, demagogues and religious fanatics. It is a bible for progressives and a rallying cry for moderate, secular liberal democracy.

Diogenes

Enlightenment Now by Stephen Pinker (2018 edition)

I agree with Bill.

Gates, that is. Bill Gates. The front cover of the paperback edition of Enlightenment Now boasts a striking quote from the co-founder of Microsoft, multi-billionaire and philanthropist: “My new favourite book of all time”. Hyperbole? Well, perhaps, but Enlightenment Now is good, very good — an absolute must-read for progressives in these benighted times.

Steven Pinker first appeared on my radar about six years ago when I took a chance on The Better Angels of Our Nature, the ‘other’ book in a Waterstones ‘Buy one, get one half-price’ offer. Something of a punt in the dark, this impulse purchase demonstrated the influence the high-street chain exerts through its store layout choices and promotional campaigns. Would I have selected the book in any other circumstances? Almost certainly not. Knowing nothing of the author (of whom, more below), the book was shouting ‘trendy’ (to be clear, that’s a bad thing), but I was intrigued by its self-stylisation as “a history of violence and humanity” as well as its breathtaking ambition. It wasn’t always like this.

By way of background, a mea culpa: I plead guilty to years of appalling narrow-mindedness. From sixth-form days way back when, my reading interests extended little further than modern British and European history and politics. One shelf after another filled up with books drawn from a narrow circle of academic historians, political biographers, politicians, broadsheet journalists — or some combination of the above, people like Michael Foot. Hidebound by conservatism, I indulged year after year in comfort reading, to the extent even of skipping the arts and culture surveys to be found in most general histories.

The rigid compartmentalisation condemned in CP Snow’s Two Cultures (which Pinker references) — the one scientific, the other literary — ensured that I neglected even to entertain the notion that a science-grounded book could be read for pleasure. This was less intellectual snobbery (Snow’s charge) and more the absence of three key intellectual attributes on my part: a solid grasp of basic science and mathematics, confidence and — most important of all — curiosity. Reluctant to sail beyond the near horizon, seasickness struck whenever I dared venture out of sight of the calm, comforting shores of modern political history.

My own enlightenment — if that is not too grand a word — came achingly slowly, beginning with the occasional history of some earlier time or place; my interest in Marxism led me to the English Civil War, for example. Peter Ackroyd’s felicitous prose was a sure guide through the byways of early England, having chanced upon the initial volume of his planned six-volume history from a shop specialising in remaindered books (volume five came out recently). The Shield of Achilles by Phillip Bobbitt was a challenging but rewarding introduction to multi-disciplinary writing. By the time I picked up Peter Watson’s Ideas: A History about ten years ago, I was sold: an ambitious, sprawling ‘intellectual history’ of just about everything — from the beginnings of civilisation, language, religion and writing to the turn of the twentieth century and Freud, Nietzsche and modernism. Watson’s A Terrible Beauty is equally good on modern times.

I credit the incomparable Richard Dawkins with curing my myopia, enabling me to see that the scientific community is equally capable of writing in an elegant and arresting manner. The God Delusion combined an impressive knowledge of religion and ethics with science, history and philosophy. Now I read the likes of Climbing Mount Improbable and The Ancestor’s Tale for pleasure, even if the science quickly passes over my head (though Dawkins’s more recent The Magic of Reality — written for young people but great for buffoons like me — is a splendid introduction to the mysteries of the scientific world). A Damascene conversion of sorts.

Better Angels, then, chimed with my new-found interest in culture and ideas, principally science, philosophy and religion, and sprawling thematic histories. It delivered in spades. A Harvard professor, Pinker’s field is cognitive science, which (as best as I can narrow it down) involves the study of the use of language, the workings of the brain and psychology, the mind and human nature. But Pinker’s writing is a polymathic tour-de-force: he seems equally at ease with history, philosophy, political science, linguistics and statistics. He writes with utter believability, supporting his arguments with a staggering array of empirical evidence, regularly citing up-to-date research and effortlessly deploying pithy quotes from thinkers old and new.

His recent Enlightenment Now picks up the same central argument as Better Angels that — notwithstanding your everyday impressions and assumptions — the world is in fact becoming a better place. Not perfect, note, but better. Not the smallest achievement of the book is the reproduction of 88 graphs, carrying data on everything from calorie intake and childhood stunting to retirement, life satisfaction and loneliness, in order to demonstrate in visual form his core argument about human progress.

At first read, his thesis feels counter-intuitive and simply wrong, at odds with the news that confronts us every single day (he has a convincing theory about this too, of course). Just in the last few days, for example, we have read of an appalling massacre in Sri Lanka, of civil war in Libya, of unrest in Algeria and Sudan, of continuing austerity, cuts and rising debt, of rising knife crime, of air pollution, of species extinction and of other climate-change perils. A typical newsweek, in other words.

The sceptic might choose to start with Pinker’s thought experiment. Ask yourself when in history you would want to be born, assuming that you had no control over where in the world you were born, your economic and social circumstances, your gender, your skin colour, the state of your mental and physical health and so on. The answer, he says, is an emphatic one: you would want to be born now.

Pinker focuses not on the ephemeral, the quotidian or the blip — the stuff of the daily headlines — but on longer-term patterns and trends. The core of the book is a demonstration of his belief that human progress is an empirical hypothesis that can be tested. In one scintillating chapter after another, he does exactly that, examining everything from personal safety and war to education, health, longevity and so on.

Pinker is clear-sighted about the enemies of progress: intuition, religious faith and scripture, authority and unquestioned obedience. Too often, we deny the very fact of progress, and he outlines a variety of fallacies and cognitive biases — the availability heuristic, confirmation bias, negativity bias and so on — to which we are all prone. This is gripping stuff, our all-too-human flaws and failings. We are often unreasoning and irrational, generalising from anecdotes, seeking to confirm prior beliefs, reasoning from stereotypes, ignoring evidence that disconfirms and so on. Nevertheless, his case is that, since the Enlightenment two hundred years ago, we have used reason and science to improve our knowledge and understanding, to overcome our cognitive weaknesses and thereby enhance human flourishing.

He rejects the idea of any kind of ‘Grand Plan’, a cosmic force of God, nature or history propelling us inexorably forward. Progress has been hard-won and must not be taken for granted. We have learned to use the tools of reason to combat unreason and irrationality: free speech and open criticism, fact checking, empirical testing and sober, logical analysis. Pinker is a champion of science and scientific reasoning, and of humanism, the belief that the ultimate moral purpose is to enhance the flourishing of individual human beings (as opposed to the tribe, race, faith etc). He argues that forces of cosmopolitanism — education, art, mobility, urbanisation — have helped develop what he calls our ‘circle of sympathy’, our sense of compassion, our ability to empathise and our concern for the welfare of others. I remember a similar point being made about the rise of the novel in the eighteenth century by, I think, Sebastian Faulks.

Pinker is difficult to categorise. It would certainly be far too simplistic to pigeon-hole him as a ‘lefty liberal’. He believes in the efficacy of free trade, market-based economics and free enterprise (though not of unregulated, red-in-tooth-and-claw capitalism), detests ‘political correctness’ — something else that he believes inhibits progress by feeding the false narrative of populists and anti-progressives — and espouses a variety of policy positions anathema to many on the left. He is sanguine about developments in artificial intelligence, adopts a moderate position on climate change (in a nutshell, we have serious problems but it’s not all doom and gloom, and extreme solutions are not the answer) and supports nuclear power and genetic modification of crops.

We live in dark times. The forces of irrationalism and anti-progressivism are on the rise across the world: fascism, populism, nativism, authoritarianism, racism, religious fundamentalism. Enlightenment Now is thus a profoundly welcome book, a worldview diametrically opposed to that offered by populists, demagogues and religious fanatics. It is a bible for progressives and a rallying cry for moderate, secular liberal democracy. Michael Gove famously claimed during the 2016 Brexit referendum that “the people in this country have had enough of experts”. Pinker loudly and proudly proclaims the value of learning and of experts. He offers hope, but it is hope grounded not in faith but in reason and in evidence, welcome sustenance for even the most Panglossian of optimists.

Darkest Hour: Film Review

‘Darkest Hour’ offers us drama and tension aplenty, emotional highs and lows, and the usual cast of heroes and villains. In a welcome challenge to the ‘great leader’ myth, Churchill himself commits numerous tactical blunders, shows himself prone to wishful thinking, and is overcome by doubt and indecision — his own darkest hour. As the tension mounts, with Britain’s position seemingly hopeless and his critics ranged against him, his spirits reach their lowest ebb.

Diogenes

The year is 1940 and Britain is in dire straits. Abroad, the German army is sweeping across western Europe, a defeatist mentality paralyses the French top ranks, and the British army faces imminent annihilation at Dunkirk, probably to be followed by the invasion of Britain itself. At home, Churchill must negotiate a fragile coalition government, a divided Conservative Party, and rebellious and ambitious cabinet colleagues.

Darkest Hour, the 2017 film starring Gary Oldman that deals with Churchill’s first few weeks as prime minister in May 1940, inevitably resonates in this time of Brexit-related angst: the UK’s relationship with the European continent is currently under the microscope as never before in peacetime, with not a little hyperbolic talk about existential threats to our freedom and independence.

These tumultuous events of 1940 and Britain’s survival were, of course, exhaustively mined by Britain’s wartime propaganda machine, turning calamitous defeat and near-disaster into a form of national triumph. Ministry of Information shorts, such as Channel Incident (starring a young Peggy Ashcroft) and Neighbours Under Fire, trumpeted the indomitable will of the British people – the ‘Very Well, Alone’ mood of popular defiance also captured in David Low’s cartoons of the time and the ‘spirit of the Blitz’ in the face of the Luftwaffe’s aerial onslaught.

I have discussed elsewhere the issue of ‘fake history’ and film — questions of historical accuracy and fidelity to the facts, the portrayal of people and events from the past, and the inevitable trade-off between historical ‘truth’ and entertainment. What makes Darkest Hour compelling viewing — beyond undeniable echoes in our current political travails — is the knowledge that those wartime propaganda lines about defiance and British exceptionalism have now been resurrected and shamelessly peddled by cheerleaders in the diehard Brexit camp to support their views about the Brexit negotiations, the opportunities and threats posed by a no-deal outcome, and our current crop of political leaders.

Darkest Hour includes virtually no scenes of actual fighting, though the reality of Britain’s perilous strategic position casts its shadow across virtually every scene. The focus of the film is essentially Winston Churchill, hailed by many — especially on the right — as our national saviour. In 2002 (Golden Jubilee year, of course), he was proclaimed the greatest Briton in a BBC poll, and ‘he’ featured prominently in the opening ceremony of the London Olympics. To be fair, and perhaps in an indication of our changing national temper (or maybe just a reflection of the BBC2 audience), he lost out to Alan Turing and others in a 2019 BBC poll of the twentieth century’s greatest icon.

Churchill is arguably the most instantly recognisable figure from our past: the huge cigar, the V-for-Victory salute and the wobbly jowls delivering soaring oratory are etched into the popular consciousness. One effect of biographies and biopics (the good ones, anyway) is to flesh out and ‘humanize’ distant figures, uncovering something of the real person behind the myth. In Darkest Hour, we see glimpses of the husband and family man, the man of privilege baffled by the Tube map, the playful man giggling with the secretarial staff and (crucially) the man of doubt. His eccentricities and larger-than-life character are fully on display, dictating memos from his bed (and from the bathroom), consuming prodigious amounts of alcohol, berating his personal staff for the slightest of errors.

One cannot help but feel that aspects of Churchill’s personal conduct, long dismissed — perhaps even applauded — as quirky, eccentric and idiosyncratic, would in today’s #MeToo climate be condemned as unacceptable bullying and sexist behaviour. Films about personalities and events from the past nevertheless reflect the mood, norms and expectations of the times in which they were made. With diversity and inclusion society’s current watchwords, any film about events dominated almost exclusively by socially privileged white men will throw up interesting challenges for director and scriptwriter.

In the film, a key role is therefore assigned to a woman, Elizabeth Layton. Though a lowly secretary, the script manoeuvres her close to the action and the locus of power, often involving her in intimate, one-to-one situations with Churchill (intimate in the sense that both can reveal hidden worries and doubts). Her role is as a proxy, a personification of the British public at large, their hopes and fears, their questions and concerns. She is fearful but resilient, curious to know more, and able to handle the unpleasant, unvarnished truth. Meanwhile, Churchill’s wife, Clemmie, is the steadying influence behind the scenes. More than just the dutiful wife, she gently admonishes the great man when he behaves like an ass.

Darkest Hour offers us drama and tension aplenty, emotional highs and lows, and the usual cast of heroes and villains (with, in this case, Neville Chamberlain perhaps somewhere in the middle). In a welcome challenge to the ‘great leader’ myth, Churchill himself commits numerous tactical blunders, shows himself prone to wishful thinking, and is overcome by doubt and indecision — his own darkest hour. As the tension mounts, with Britain’s position seemingly hopeless and his critics ranged against him, his spirits reach their lowest ebb. He becomes forgetful and — the ultimate catastrophe for a politician feted for his ability to communicate — struggles to find the words, before rediscovering his mojo with the help of the great British public in the controversial ‘Underground’ scene — controversial in the sense that it is purely fictional.

The George VI presented to us is also of interest. Though the icy relationship between Churchill and the king thaws somewhat as the film progresses, the viewer will struggle to reconcile this monarch with Colin Firth’s portrayal in The King’s Speech. In the latter, he is warm, vulnerable and all-too-human. Here, he is remote, cold, bigoted and snobbish. The scene where he surreptitiously wipes his hand behind his back after it has been kissed by Churchill is particularly telling. Later, in an ironic turn, it is the king who urges the prime minister to listen to the voice of the people, precipitating Churchill’s journey of rediscovery on the Underground.

The role of arch-baddie is, however, reserved for Lord Halifax, the king’s confidant and political puppet-master, pulling Chamberlain’s strings in a bid to engineer a compromise peace with Hitler, thus preventing a German invasion and safeguarding the British Empire. He is calculating and scheming, refusing to take on the role of prime minister after Chamberlain’s resignation as the time is ‘not yet right’. The England (sic) he cherishes and seeks to preserve is that of the upper-class gentleman and country estate, a land of strict social division, of privilege and entitlement. Compare this with the portrayal of the ordinary Englishman and Englishwoman: patriotic, decent and resolute.

Films recreating events from the past must find imaginative ways to contextualise events, plugging gaps in the viewer’s historical knowledge and ensuring that the storyline makes sense. Here, for example, Churchill explains to someone who would have known the situation perfectly well that the king disliked him because he (Churchill) supported his (George’s) brother’s desire to marry Wallis Simpson. To establish the reasons for Churchill’s unpopularity with many Tories, we are offered a montage of politicians in whispered discussion, each with a gripe against Churchill: it is a ‘greatest hits’ of his errors and failings — serial infidelity to the Conservative Party, Gallipoli, India and the return to the Gold Standard.

The scenes in the Chamber of the House of Commons are pure theatre — the bear-pit atmosphere and the dramatic lighting, as if a solitary spotlight were picking out the speaker at the despatch box, with the surrounding benches (front and back) almost in darkness, the more so to accentuate order papers furiously batting the air.

The debates themselves do not (inevitably) ring particularly true. For example, the two-day debate that led to Chamberlain’s resignation is here shortened to about five minutes. Labour’s Clement Attlee is forensic and withering, far too much so, if the recent biography by John Bew is to be trusted. Crucially, the damning verdict of backbench Conservative MP Leo Amery, invoking Cromwell to the Rump Parliament — “In the name of God, go!” — is expunged from the record, as it wouldn’t serve the narrative, namely that Churchill did not have the Tory backbenches behind him and that his support came from the Labour benches. To the end, Chamberlain appears to command the loyalty of the Conservative MPs, a surreptitious wave of the handkerchief his signal to the backbench troops whether or not to show their support for the new prime minister.

Some of the points made in this article were also made in the article ‘Fake History’ and Film.

‘Fake History’ and Film

Elizabeth I meets Mary, Queen of Scots! Churchill rediscovers his mojo on the Underground! Homosexual genius Alan Turing is blackmailed by Soviet spy John Cairncross at Bletchley Park! Hmmm. Memo to self: ‘Films based on historical events are not documentaries. Stop judging them as if they are.’

Diogenes

The above are not happenings in an alternate reality (to borrow some American sci-fi terminology) but scenes from films about real people, their lives mediated through ‘Hollywood’ — just three examples of what we might call ‘fake history’ offered up for our viewing pleasure in well-known films released over the last few years about famous people and/or events.

The buzz surrounding two recent films that focus on the lives of female monarchs from Britain’s past — Mary Queen of Scots (about the rivalry between the eponymous Mary and Elizabeth I) and The Favourite (set in the court of Queen Anne) — has poured lighter-fuel on a debate that seems to smoulder away all but unnoticed before re-igniting whenever a blockbuster film portraying iconic figures and events from the past is released.

The usual suspects — lower case, not the Kevin Spacey film — have again been hauled in to take up their place in the line-up of cinematic shame: films such as The Patriot, Braveheart, Saving Private Ryan, all charged with the heinous crime of playing fast and loose with ‘the truth’. The only surprise is that nobody appears to have brought up Valkyrie, in which Tom Cruise comes within minutes of bringing down the Third Reich.

The debate about ‘fake history’ operates at a number of levels, with questions of historical accuracy morphing into arguments about how much fidelity to the facts actually matters and broader discussions about representations of the past.

At its simplest is a binary question, the answer to which is either ‘yes, this did happen, that’s accurate’ or ‘no, that didn’t happen, that’s not how it really was’. We’re not just talking feature films and television dramas, of course. Any self-respecting pub quizzer will doubtless remind us that when Cassius declares in Julius Caesar that “The clock has stricken three”, Shakespeare had (deliberately or otherwise) penned an anachronism: mechanical clocks of that type were not around in the first century BC.

Playing ‘fake history’ is fun for all the family. BBC Bitesize (targeted at a young audience) recently ran an online article highlighting inaccuracies in eight popular films — the Alpine escape of the von Trapp family from the clutches of the evil Nazis in The Sound of Music, the death of the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius in Gladiator, the clothing worn by thirteenth-century Scots in Braveheart. And so on.

There are deeper issues involved, however — not least the rather important question of what we mean by ‘the truth’ — and unsurprisingly these trickier matters attract the interest of heavyweight journalists and academic historians alike. In this latest round, for example, Oxford historian and BBC4 regular Dr Janina Ramirez was commissioned to write a piece on The Favourite for the Sunday Times. The Guardian journalist Simon Jenkins set out his views in a typically forthright piece headlined The new threat to truth: fake history films. He accused film-makers of claiming “the right to mis-sell films as history”, sexing them up with invention, out of fear that “accuracy will not put bums on seats”.

This terrain encompasses all ‘texts’, not just headline-grabbing films about famous people and events found on the school history curriculum. Take two other recent films, both of which might well have come with some variation or other of the words ‘based on real events’ attached. And what is ‘based on real events’ exactly — a neutral statement, a caveat, a disclaimer, a cop-out?

The first, Stan and Ollie, uses a Laurel and Hardy music hall tour of Britain in the twilight of their careers as a vehicle for exploring the duo’s relationship. As a narrative frame, it works brilliantly well, though I don’t know enough about their actual story to make confident assertions about how accurate it all is. My gut instinct is to doubt the literal ‘truth’ of certain events depicted, such as the on-set arguments between Stan and Hal Roach and Ollie’s collapse in Worthing, and the accuracy of the portrayal of characters such as the scheming, oleaginous impresario, Delfont.

The second, meanwhile, I have discussed in detail elsewhere: the Freddie Mercury biopic Bohemian Rhapsody, a film that wields a knife with wilful abandon as it cuts the Queen story to shreds. Guitarist Brian May has spoken of his journey of understanding as an executive producer, ending (he says) with the realisation that a film is a very different beast from a documentary — but that both are valid artistic means of telling a story. He is, in essence, criticising those Queen fans unwilling or unable to see beyond the film’s cavalier approach to the facts. That formula — ‘based on real events’ — is, if nothing else, an elastic one. Maybe that’s part of the problem: how exactly are viewers expected to know how literally to believe what is being portrayed?

Of course, should we so choose, we refer to Wikipedia or whatever for (usually) in-depth analysis of the accuracy of this or that scene, portrayal or storyline. My immediate reaction after watching the excellent film The Exception, about Kaiser Wilhelm II in exile in Holland in 1940, was to reach for a biography of the ex-German emperor to clarify how much of it was true (answer: not much). But how many of us ever bother? It’s a fair bet that many film-goers and TV-watchers don’t give the matter a second thought and/or don’t particularly care whether a film is accurate or not — as long as they are entertained.

The business of films, in more than one sense, is first and foremost to entertain — fair enough. Self-styled “public historian, broadcaster, author, and historical consultant to Film & TV” Greg Jenner disagrees with the Simon Jenkins line quoted above, tweeting recently about the importance of historians engaging with pop culture:

Historical films are not “fake history”; they’re stories. They aren’t documentaries and nor do they try to be. So long as historians are able to publicly respond (which we do in droves) these films are helpful, not a hindrance, in stimulating public fascination with the past.

Greg Jenner

In other words, if films are stimulating public interest in the past, that’s surely a good thing, right? Jenner says that historians are taking part “in droves”. I accept that it would be churlish to ignore or downplay the tireless efforts of a wide range of academics and others (a big shout-out here to classroom teachers) to engage with the public via an ever-widening variety of platforms — from websites and podcasts to public lectures and TV programmes.

But a nagging question remains: beyond a stratum of enthusiastic, educated amateur history buffs — to borrow Eric Hobsbawm’s phrase, “that theoretical construct, the intelligent and educated citizen” — how much actual purchase is there at grassroots level among non-history buffs? I refer, perhaps, to those who drink at that bustling yet ever so elusive pub, the Dog and Duck, spoken of in hallowed terms by politicians and media commentators alike, where issues of the day are discussed by ‘ordinary’ folk over a warm pint of beer or glass of wine.

I also accept that, although accuracy obviously matters a great deal in historical re-creations, it isn’t the be-all and end-all — and perhaps not even the most important element of a film. A film may include plenty of inaccuracies, even wholly fictionalised situations, and yet still be bloody good, as Stan and Ollie certainly showed (assuming the narrative isn’t all literally true). After all, most if not all the dialogue in every historical film is made up: who knows who said what to whom in reality?

A great artist — actor, writer or director — uses their raw material — part-fact, part-fiction — to capture and convey the essence of a person or situation, hopefully revealing deeper or more complete truths. In that sense, even if some of it didn’t really happen, Stan and Ollie still stands up as an utterly delightful window into the world of Laurel and Hardy, funny, moving and sad, a warm-hearted, bittersweet film about friendship, fame and the inexorable passing of time.

I further agree that it is naive and simplistic to expect ‘the truth’ (singular). A ‘text’ — a book, a play, a film, a painting — is a representation (literally, a re-presenting) of the past, an authorial construct based at least in part on the selection and presentation of information. As the historian Anthony Beevor has argued persuasively, the price of supping with the Hollywood devil is stomaching a degree of creative licence for film-makers with regards to ‘what really happened’.

At its worst, however, this Faustian pact leads to oversimplification (not to mention ‘dumbing down’), serious distortion and the flattening of individuals and historical situations into one-dimensional caricatures. It filters out complexity, balance, nuance, ambiguity and paradox. It does not permit doubt, ambivalence and confusion. In other words, it comes at the expense of the stuff of reality and cheapens the study of the past. Ask John McDonnell, who foolishly accepted the request to reduce the life and career of Winston Churchill to a single word.

Films are also products of their time, reflecting the mood, norms and expectations of the day. However, unless handled skilfully by writer and director, they can end up seeming uncomfortably forced and contrived. Darkest Hour, the 2017 film dealing with Churchill’s first few weeks as prime minister in May 1940, is an intriguing case in this respect. With diversity and inclusion society’s current watchwords, any film about events dominated almost exclusively by socially privileged white men will throw up interesting challenges.

In the film, a key supporting player is therefore a woman, Elizabeth Layton. Though a lowly secretary in the typing pool, she is manoeuvred close to the action and the locus of power, often involved in one-to-one situations with Churchill. Her role is as a proxy, a personification of the British public at large, their hopes and fears, their questions and concerns. She is fearful but resilient, curious to know more, and able to handle the unpleasant, unvarnished truth. Meanwhile, Churchill’s wife, Clemmie, is the steadying influence behind the scenes. More than just the dutiful wife, she gently admonishes the great man when he behaves like an ass.

In the film’s ‘Underground’ scene — wholly fictional, of course — the passengers (a handy cross-section of the British people — men, women and children) are united, defiant and resolute. It is like a David Low cartoon brought to life, a re-creation of the mood portrayed in the official propaganda films of the time and later mythologised as ‘the spirit of the Blitz’. It is a version of history for the Brexiteers.

One of the passengers is a young black man, who appears to be in the company of a white woman — whether friend, lover or spouse is left unclear. While not wholly implausible in 1940, this depiction of relaxed attitudes to inter-racial relationships (and even friendships when involving people of the opposite sex) nevertheless feels anachronistic, and it is certainly very different from attitudes portrayed in the recent Rosamund Pike/David Oyelowo film set partly in late-’40s Britain, A United Kingdom.1

And of course, as consumers of history — watchers of films, readers of books etc — we sprinkle our diet with liberal (small ‘l’) helpings of our own beliefs, values and biases. With our relationship with the European continent currently under the microscope as never before in peacetime, and with much hyperbolic talk about threats to our freedom, Darkest Hour resonates in this time of Brexit-related angst. Would the ‘ordinary’, non-political, non-Eurosceptic viewer have felt this way about the film ten years ago, say?

Or take the films of Mel Gibson as both actor and director. Now something of a bête noire of the film industry and the wider public2, how much are people’s opinions of his work influenced by opinions of the man (drunk, misogynist, Christian extremist, anti-Semite are some of the labels attached to him)? Or, mutatis mutandis, re-read this paragraph, replacing the name in the first sentence with ‘Woody Allen’ or ‘Kevin Spacey’.

As a keen student of history, I feel protective of the people, events and circumstances of the past, and instinctively recoil at falsification, at bias and at individuals and their reputations being brazenly glorified or traduced. When I open a history book — especially on the many topics about which I know little or nothing — I bring to it certain expectations and assumptions. First and foremost, I want accuracy and fidelity to the facts. Secondly, I trust that the representations shown to me — and judgements offered — by the writer are judiciously reached, based on the best available evidence. I want to learn about three-dimensional characters, not black-and-white ‘goodies’ and ‘baddies’. Where doubt about the evidence exists, I want it to be made clear that doubt exists.

Is it too much to expect all this of a film — and to be entertained as well? In the week of Bruno Ganz’s death, it is worth remembering what can be achieved. Though no Hollywood blockbuster, and perhaps known to many people only via much-circulated social media memes with joke subtitles, Downfall — and particularly Ganz’s electrifying portrayal of Adolf Hitler — demonstrates that films can indeed combine serious, well-researched history and gripping entertainment. More, please.

Notes

Queen Songs Ranked 20–01

At last — cue the opening drum roll from Innuendo — we arrive at what this fan considers to be the twenty greatest Queen songs. The best of the best. It is surprisingly difficult to write anything about these twenty gems — especially the singles — as so much has already been said, not least about Bohemian Rhapsody, which — major spoiler alert! — did make my final twenty. The list is heavily weighted in favour of the ’70s, with five of the tracks coming from Queen II and five from A Night at the Opera. I have written elsewhere about the problems of choosing a ‘best’ album: the four albums from Queen II to A Day at the Races are all quite exceptional. There is a fairly even spread of Freddie and Brian songs here (with one contribution from Roger), though Brian wrote all of the songs in my top three and sang two of the songs in my top ten. Enjoy.

Click here for details about how I compiled the list and to start from the beginning (number 185).

20. Killer Queen (Mercury), Sheer Heart Attack, 1974

Freddie’s song about a high-end prostitute has a lighter feel after the dense sound and full-on fury of much of Queen II. The penchant for witty lyrics and camp, theatrical delivery was typical of Freddie in the ’70s — think of Lazing on a Sunday Afternoon, Seaside Rendezvous and Bicycle Race. Their first big hit single, it’s often forgotten that it was actually a double-A-side with Flick of the Wrist (the one you won’t have heard on Tony Blackburn’s show, as Brian said at the Rainbow). Best moment: the guitar solo — one of Brian’s favourites, so he has indicated.

19. Teo Torriatte (Let Us Cling Together) (May), A Day at the Races, 1976

After Brian’s billet doux to America (Now I’m Here) came this paean to Japan, written after two incredibly successful tours there. Utterly gorgeous from start to finish, the song starts conventionally enough (albeit with a chorus partly sung in Japanese), until Brian reaches for the power chords and Freddie delivers a sensational middle eight (“When I’m gone / They’ll say we’re all fools and we don’t understand”). The climax is an exquisite multi-tracked choir effect, accentuating the inclusive message of the song. The HD mix featured on the 2011 remasters is sublime.

18. Nevermore (Mercury), Queen II, 1974

A short yet quite delightful piano ballad from Freddie. The title is perhaps drawn from Edgar Allen Poe’s poem The Raven – some of Freddie’s early lyrics contain literary allusions. The piano parts are gorgeous, the words — beautifully sung — are tender and touching, and the backing vocals are magnificent. Nevermore is a (rare) example of where the BBC session version didn’t really work (an indication, perhaps, of how important the backing vocals are in the song). Best moment: the angelic choir sound at 0:58.

17. Innuendo (Queen), Innuendo, 1991

Rolling, sweeping, majestic. Innuendo casts off the self-imposed straitjacket of the conventional four-minute pop-rock song that constrained the band’s creativity as mega-stardom beckoned in the ’80s. In its epic scale, Innuendo recaptures the youthful idealism and spirit of adventure of songs like The March of the Black Queen and The Prophet’s Song. Like the rising of the sun and the incessant motion of the tides, music and lyrics combine to evoke a boundless, timeless universe — “’til the end of time” indeed. Best moment: a toss-up between the sparse acoustic interlude at 2:45 and Brian’s magnificent guitar from 4:19 onwards.

16. Father to Son (May), Queen II, 1974

An appropriately guitar-rich epic, this is Brian’s loving tribute to his father, Harold, with whom he of course built the Red Special. The centrepiece is Brian’s sweeping, multi-layered solo, yet the whole song illustrates the prevailing Queen motif at that time — to fill every possible space with sound, right from the opening power chords after the final strains of Procession fade away. The Procession / Father to Son opening of the March ’74 Rainbow concert is possibly the most powerful opening to a live album ever. Best moment: Brian’s lines expressing the unconditional love between parent and child — “But the air you breathe / I live to give you”.

15. White Man (May), A Day at the Races, 1976

Another breathtaking exploration by Brian of the possibilities of two-part and three-part guitar harmonies, White Man is a snarling howl of anger and rage at the tragic fate of America’s native peoples, all but wiped out by the onward march of European so-called ‘civilisation’ — “the hell you’ve made”. Freddie brilliantly conveys the pain and anguish in his throat-shredding vocals. Best moment: guitar and drums from roughly 3:02 and particularly Roger’s drums at 3:09.

14. The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke (Mercury), Queen II, 1974

The original and best example of Freddie’s penchant for writing fast-paced quirky arrangements, accompanied by witty or unusual lyrics — Seaside Rendezvous, Mustapha, Bicycle Race and the operatic section of Bohemian Rhapsody follow in the same tradition. Written around a painting by troubled nineteenth-century artist Richard Dadd and obviously the result of painstaking research (not something one would associate with later-era Freddie). Best moment: “What a quaere fellow!”

13. Radio Ga Ga (Taylor), The Works, 1984

A spectacular return to form after the misfiring Hot Space, Radio Ga Ga has achieved near-legendary status, not least as a result of its inclusion in the Live Aid set. Programmed drums notwithstanding (and a guitar sadly buried in the mix), it is a brilliant homage to the apparently dying world of radio — ironically, supported by one of their most ambitious and best videos — with great bass from John and an anthemic, show-stopping chorus. Best moment: “So stick around ‘cos we might miss you / When we grow tired of all this visual”.

12. Seven Seas of Rhye (Mercury), Queen II, 1974

After the prolonged, meandering opening to their first single, Keep Yourself Alive, their second single took them to the other extreme — delivering everything bar the kitchen sink in a spellbinding opening thirty seconds. A brilliantly crafted slice of rock (and one of their more ‘glam’-sounding efforts at a time when ‘glam’ was dominating the charts), with typically (for early-era Freddie) obscure yet compelling lyrics. Best moment: the snarling guitar at 1:51 after “Then I’ll get you!”.

11. Don’t Stop Me Now (Mercury), Jazz, 1978

Freddie’s hymn to the hedonistic lifestyle. An exceptional piece of commercial ‘pop’ music, comfortably the stand-out track from the patchy Jazz sessions and the closest Queen should have veered in the direction of disco. Now one of Queen’s most recognisable songs, it’s hard to believe that it only reached number 9 in the British charts. Unlike (it seems) many fans, this fan prefers the ‘long-lost guitars’ version from the 2011 re-releases and the ‘revisited’ version from the 2018 movie soundtrack, both of which offer a more ‘traditional’ Queen sound. Best moment: John’s bass at roughly 1:31.

10. The Prophet’s Song (May), A Night at the Opera, 1975

In some respects a companion piece to Bohemian Rhapsody from the same sessions, this is probably the most gloriously sprawling, ambitious and experimental song the band (in this case, mainly Brian) attempted — from the opening notes of the toy koto onwards. Mystical themes, delightful guitar harmonies and bizarre vocal effects combine to deliver eight minutes of bewildering brilliance. Best moment: the power of the bass-drum-guitar combination after “Listen to the madman!” at roughly 5:51.

09. Somebody to Love (Mercury), A Day at the Races, 1976

Freddie’s nod to Aretha Franklin and the gospel sound, this is a suitably over-the-top follow-up to Bohemian Rhapsody. A brilliant vocal performance from Freddie, wonderful gospel choir arrangements involving Freddie, Brian and Roger, and a great overall sound. Freddie himself cited it as a better song than Bohemian Rhapsody in terms of songwriting. It also translated exceptionally well to the stage, particularly the closing section of the song. Best moment: Freddie’s vocal combining with Brian’s guitar for “But everybody wants to put me down” from 1:45.

08. The Show Must Go On (Queen), Innuendo, 1991

Like These Are the Days of Our Lives, this song captures the sad and reflective yet defiant mood of the time, with the band writing and recording in the shadow of Freddie’s approaching death. The music is magnificent, particularly Brian’s guitar and John’s bass, and somehow Freddie delivers a truly stunning vocal performance. Some of the lines are — with the benefit of hindsight — unbearably sad, not least “Inside my heart is breaking / My make-up may be flaking / But my smile still stays on”. Best moment: a strong contender for the best lyrics Queen ever wrote — “My soul is painted like the wings of butterflies / Fairy tales of yesterday will grow but never die / I can fly, my friends”.

07. Good Company (May), A Night at the Opera, 1975

Almost four minutes of utter originality and genius, courtesy of Brian, beginning with the minimalist ukulele opening and concluding with the full jazz-band sound, all of which (drums excepted, obviously) was created in the studio on the Red Special and other guitars. Has the guitar ever been used to such stunningly original effect? Overlooked too are Brian’s wonderfully witty lyrics, particularly the way he cleverly weaves multiple uses and meanings out of the word ‘company’. Best moment: it has to be the jazz-band effect.

06. In the Lap of the Gods…Revisited (Mercury), Sheer Heart Attack, 1974

Freddie was at his creative peak on the first four albums, and this is yet another outstanding piece of writing straight out of left field. A brilliant way to end the Sheer Heart Attack album, it was also used as a magnificent show-closer until 1977, accompanied by industrial quantities of dry ice, and was (for this fan at least) an even better finale than We Are the Champions, which replaced it in the live set. Best moment: the long “Wo wo la la la” final section of the song.

05. Death on Two Legs (Dedicated to…) (Mercury), A Night at the Opera, 1975

As the elegant notes from Freddie’s piano make way for Brian’s snarling guitars, a sense of menace and unrestrained fury grabs the listener by the throat and doesn’t let go. Freddie’s diatribe aimed at their former management company is a brilliantly unsettling opening to the band’s Sgt Pepper, as he hurls the insults and heaps on the abuse in line after bitter line. Best moment: it can only be “But now you can kiss my ass goodbye!”.

04. Bohemian Rhapsody (Mercury), A Night at the Opera, 1975

For many, of course, Queen’s magnum opus. What more is there to be said about this song about which so much has been said and written? Startlingly original, certainly in terms of the singles charts — and yet what is magnificent about Queen is that many of the ideas in Bohemian Rhapsody are foreshadowed in their previous work. A complete one-off … and yet so typically Queen. Magnifico, indeed. Best moment: the operatic section, if only for the sheer audacity.

03. ’39 (May), A Night at the Opera, 1975

The finest of Brian’s many wonderful songs about absence, loss and the passage of time. More fitting than the rather upbeat on-stage delivery by Freddie, Brian’s sombre vocal perfectly matches the mood of the song. Exquisite folksy acoustic guitar throughout, supported by bass drum, double bass and tambourine. Best moment: the ethereal backing vocals, especially (but not only) at 1:37.

02. White Queen (As It Began) (May), Queen II, 1974