Best Queen Singles

Another bank holiday, another ‘best Queen song’ poll – well, best Queen song since the last poll of best Queen songs. I am exaggerating, but not gratuitously so. This time it’s BBC Radio 2’s Your Ultimate Queen Song, part of Easter Monday’s Radio 2 Celebrates Queen day. Meanwhile, my Twitter feed just featured a retweet of a member of the public belting out We Are the Champions from ITV’s Starstruck (with, note, Adam Lambert as one of the judges). ITV had its own The Nation’s Favourite Queen Song programme in 2014. And hardly a month goes by, it seems, without a Queen day on Sky Arts or BBC Four.

Do people – in the UK at least – now think of Queen in the same way as they do the Beatles? It is certainly easy to be mesmerised by the headlines and hyperbole: biggest-selling UK album ever; long-running West End musical (back on in 2023); mega-grossing film; gazillions of YouTube watches and Spotify streams. The list goes on. Even tired phrases like ‘iconic’ and ‘national treasure’ might not be wholly inappropriate in Queen’s case, though I hate hearing the term ‘legendary’ used about celebrities, regardless of who they are.

Queen’s winning formula is a combination of well-recorded, accessible and timeless songs, genuine musical talent, a superstar singer who died in the prime of life, theatricality and showmanship, professionalism, nostalgia tinged with sadness and heartache, extraordinary intergenerational appeal, dependability, ruthless business sense and – in Brian May – a genuinely nice guy. It wasn’t just the band’s name that secured them the opening slot at the platinum jubilee celebrations last summer.

Will the public eventually get sick of Queen? It is, after all, hard to nip to the supermarket or sit through TV adverts without bumping into some Queen song or other. And always, always the same ones.

My favourite music channel on YouTube is Sea of Tranquility. Pete Pardo and his guests are serious (and seriously knowledgeable) music fans. A favourite catchphrase of Pete’s is I never need to hear that song again. He said those very words again in a programme I watched just yesterday – the song, Babe by Styx. There may even be a whole show devoted to played-to-death songs. (A huge shoutout to Pete, by the way, for drawing my attention to early Styx albums like The Grand Illusion and Pieces of Eight, essential listening for fans of 70s Queen.)

I don’t think I am quite at that stage yet with any Queen songs, but I may be close with one or two. The tracks released as singles are usually the ones I least concentrate on whenever I play a Queen album. I hardly ever play Greatest Hits. I can name all the tracks on Greatest Hits II but have no idea what order they come in. And, well, the less said about Greatest Hits III the better.

But how good are the singles, especially compared with the album-only tracks or even the stuff only released as B-sides and twelve-inch fillers? How good are the classics? How classic are the classics? And another question that kept on nagging away at me when I did my Queen Songs Ranked blogs back in 2018 was: what are the difficulties in coming to a judgement about how good they are?

There’s also a more basic question – what makes a good song? – but my argument here is that popular, successful, often-played singles are a particular headache when trying to compile any sort of ranking of favourite songs.

There’s Pete’s I never need to hear that song again problem of overfamiliarity, obviously. But, for me anyway, there is also the type of song that, for obvious reasons, is often selected for single release by rock bands. In common with those of other groups, Queen singles tended to follow a formula, especially as the band chased global stardom from the later 70s onwards – accessible and listener-friendly, catchy and filled with oft-repeated riffs and hooks, three or four minutes in length, and likely to have a crossover appeal. In a word, ‘commercial’. And I instinctively shy away from commercial pop songs.

I thought it would be interesting to compare my Queen rankings with some of these public polls. I went back to the BBC Radio 2 and ITV polls mentioned above and also a Classic Rock poll of the ’50 best Queen songs of all time’ that was first published in 2018 (their webpage has since been updated).

Note that we are not necessarily comparing like with like. I ranked every Queen song with any Freddie involvement – singles, albums, non-album B-sides and the handful of songs released long after Freddie’s death, such as Feelings, Feelings. The BBC invited listeners to vote for up to three of their favourite songs from Queen’s Top 75 UK chart singles, including collaborations with the band following Freddie’s death (hence the reason why Queen + The Muppets appear in the final chart – yes, really ). ITV’s website simply refers to a “representative panel of viewers”, presumably choosing from a list of singles. Classic Rock’s poll – like my rankings – covered the band’s entire output.

These polls are obviously ‘unscientific’, in the sense that the voting public is self-selecting. Take the Classic Rock poll, for example. Some of the voters will no doubt be big Queen fans. Equally, however, some participants may well be general rock fans who perhaps know little or nothing of Queen other than the singles. We just don’t know what the proportion is between these two groups. The BBC and ITV voters only had the singles to choose from, of course.

Anyway, here is the BBC poll’s top 10:

- Bohemian Rhapsody

- Don’t Stop Me Now

- Somebody to Love

- We Are the Champions / We Will Rock You

- Radio Ga Ga

- Who Wants to Live Forever

- Killer Queen

- Under Pressure

- Love of My Life

- These Are the Days of Our Lives

The results of the other two polls are not too dissimilar. I Want to Break Free is number 4 in the ITV poll (it was the BBC’s number 11), and ITV have Somebody to Love at number 10 and Who Wants to Live Forever one place lower. Classic Rock’s top three were the same as the BBC’s. Classic Rock’s top 12 were all singles (and remember that their voters could choose any Queen song, single or non-single). In total, seventeen songs out of Classic Rock’s top 20 were singles.

At least, that’s if we are counting Love of My Life, which didn’t feature in ITV’s shortlist. The original song was on 1975’s A Night at the Opera, but it was a live acoustic version (from the Live Killers album) that was released as a single, in 1979. Its top-10 placing here indicates that many now see it as a Queen classic, which raises an interesting question about the various and sometimes circuitous routes by which songs acquire ‘classic’ status. After all, though now a nailed-on classic, Don’t Stop Me Now only reached number 9 in the British charts when it was originally released. Who Wants to Live Forever didn’t even get in the UK Top 20.

Love of My Life bombed spectacularly when it came out as a single (it reached number 63) – and yet here it sits in the BBC top 10. It’s cut-through appeal and longevity probably come from the iconic 1986 Wembley show. Aagh, that word ‘iconic’ again – but arguably justified in this case, at least in its sense of a moment or image (or in the case of Wembley a whole series of images) that has seared itself into the public consciousness. Think of the band’s stage outfits, particularly Freddie’s yellow jacket, the poses he struck, the robe-and-crown finale – it’s all there in your head. Love of My Life is also now, of course, a pivotal audience-participation moment in the Queen + Adam Lambert live show with, on recent arena-filling tours, a special ‘appearance’ by Freddie.

We Will Rock You fits into this category too. The BBC paired it with We Are the Champions. ITV and Classic Rock both listed the two songs separately. We Will Rock You was not – as is widely misremembered – a double A-side (except in the USA and a couple of other countries), but is actually an example of a B-side that has become at least as well known as the A-side.

It’s a song I struggled to place in my rankings. It ended up at number 94 – mid-ranking, though I’m not sure I could tell you why. It is instantly recognisable, sung in sporting stadiums the world over to this day, nearly fifty years after its release. On the other hand, it has the simplest of song structures, is ridiculously repetitive and includes very little actual musicianship.

And can Bohemian Rhapsody be anything other than number 1? Well, yes. Freddie himself is on record as saying that Somebody to Love is a better piece of songwriting than Bohemian Rhapsody. When I did my rankings, I listened to every song again at least once, forcing myself to keep an open mind and not to rely either on judgements that I have settled on over the years or on what might be described as ‘received wisdom’ — in other words, what everyone else says.

The trouble is that the real ‘biggies’ are soooo familiar, ubiquitous even — and probably none more so than Bohemian Rhapsody. Add to that the fact that everyone — but everyone — will tell you how incredible it is. It’s hard to be objective. Bohemian Rhapsody is indeed an incredibly inventive, daring and original song, but so are a number of other Queen songs — The Prophet’s Song from the very same album immediately comes to mind, as does The March of the Black Queen from Queen II.

As I said earlier, I tend to steer well clear of mass-appeal ‘pop’ music, and this is reflected in my list of favourite Queen songs. Only three of my top 10 and eight of my top 20 were singles. All my favourite Queen albums are from the 70s. Their music was generally heavier, lighter, more daring, more inventive, more experimental, proggier, more diverse, more bewildering, more surprising and generally less formulaic than anything they released from 1980 onwards (with the exception, I suppose, of some of Hot Space).

Not that all Queen’s singles could be labelled commercial pop. Like Bohemian Rhapsody, Innuendo doesn’t fit the description. Both (unsurprisingly) feature high in my rankings. On the other hand, some Queen singles were extremely commercial and chart-friendly, but still rate highly in my chart because they are just so bloody good – Don’t Stop Me Now and Killer Queen, for example.

So, is it just hard for me to listen to the likes of I Want to Break Free, Another One Bites the Dust and Crazy Little Thing Called Love with fresh ears, or do I actually think that they are actually fairly mediocre (by Queen standards) songs?

I’m not absolutely sure, though I suspect it’s the latter more than the former. (All three of those songs were much better live, particularly Crazy Little Thing with its rocked-up final section, the bit after the “Ready, Freddie” response.) I do, however, know for certain that I am always far more excited whenever I hear tracks like (to take some random examples) My Fairy King, Some Day One Day and Long Away that I almost certainly won’t hear unless I make an effort to play the relevant album, which might not be for weeks at a time.

Is it snobbishness, perhaps – the mentality that you’re not a ‘real’ fan unless you like the deep album cuts? I hope that isn’t the case and that it’s more the fact that I look for a lot more in a song than just ‘catchiness’.

Anyway, here are my top 5 ‘best’ and ‘worst’ singles (up to and including 1991 when Freddie died), shown with their placing in my overall Queen chart, with the BBC placing in brackets.

My favourite Queen singles:

4. Bohemian Rhapsody (BBC number 1)

8. The Show Must Go On (BBC number 12)

9. Somebody to Love (BBC number 3)

11. Don’t Stop Me Now (BBC number 2)

12. Seven Seas of Rhye (BBC number 13)

And my least favourite Queen singles:

175. Body Language

171. Thank God It’s Christmas

159. Friends Will Be Friends (BBC number 37)

150. The Invisible Man

136. Scandal

No post found

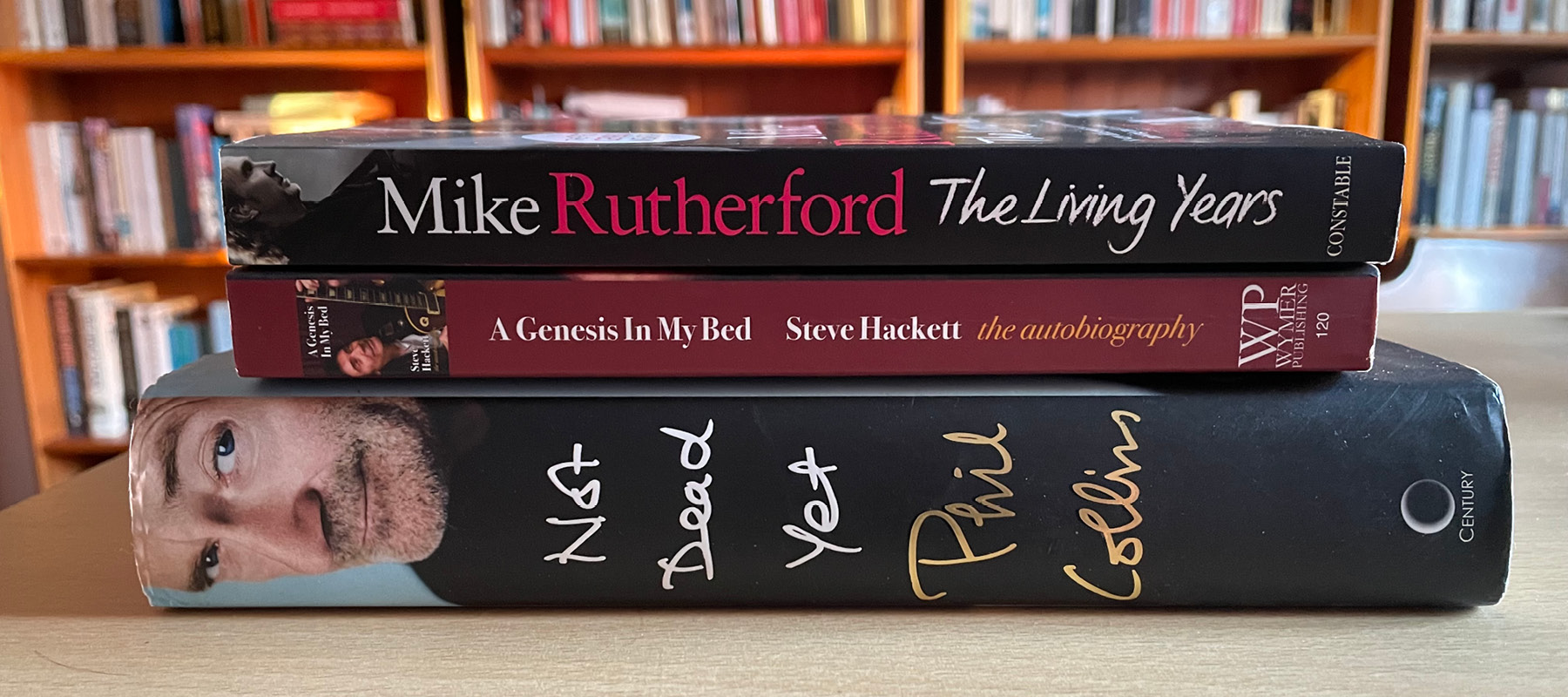

Genesis Autobiographies

Autobiographies and memoirs are not, strictly speaking, the same. Timespan, for one thing. Autobiography suggests a life story starting from birth whereas memoirs are more limited in scope, perhaps covering a particular period of time or set of circumstances (like a politician’s time in office). However, the two words are often used interchangeably, and indeed I often find myself using the words ‘memoir’ and ‘memoirs’ as shorthand for ‘autobiography’. Also, I have assumed that the subject of each Genesis autobiography discussed below actually wrote every word of it – Phil (not a ghost-writer or Phil assisted by a ghost-writer) wrote Not Dead Yet, for example – unless something gives me cause to think otherwise.

On any given day in, say, 1979 or 1980 there was a decent chance that my local library’s copy of I Know What I Like, Armando Gallo’s lavishly illustrated history of Genesis, was stashed away in my bedroom rather than propped up on the library’s shelves patiently awaiting its next borrower. I Know What I Like was my go-to guide as I immersed myself in the collection of classic Genesis albums from the 70s that started with Trespass and ended with …And Then There Were Three. (The book itself closed with the band beginning rehearsals for what became the Duke album.)

I have never much bothered with books about music and musicians (other than Queen-related stuff) and for a long time I had nothing on my shelves about Genesis. I didn’t, for example, buy the hefty (and heftily priced) Chapter and Verse book that came out in 2007. A great title and an even greater selection of photos (I borrowed my friend Dave’s copy), but a publication that carried the Genesis imprimatur – it was part of the official Turn It On Again reunion tour package of promotional goodies – was not really the kind of history that interested me much.

I did pick up a cheap copy of Genesis: A Live Guide 1969 to 1975 by Paul Russell that was first published in 2004. I was downloading a lot of bootlegs at the time, and this was a thoroughly researched analysis of and commentary on more than 160 live shows spanning the Gabriel years (check out my own Genesis bootleg history blog series). But, like all such books, its focus was a narrow and specific one, the hardcore fan its target audience.

I am not generally a reader of celebrity biographies full stop, still less celebrity autobiographies. It was a YouTube video of Phil Collins singing Against All Odds on the Jonathan Ross Show in 2016 that first piqued my interest in reading Phil’s effort. The performance was heartbreaking to watch, and yet – and therefore – compulsive viewing.

I was already vaguely aware that Phil had struggled with his health in recent years and that he was unable to play drums any more – shocking news in itself. He was a wonderful drummer. We’re all familiar with his trademark ‘gated’ drum sound that defined 80s pop – just think gorilla and drum kit – but his busy and inventive drumming style was a key ingredient of the Genesis magic in the early days. There is quite a bit of footage of Gabriel-era Genesis on YouTube but – annoyingly – the camera focuses for much of the time on the singer and not the other members of the band. So if you aren’t familiar with it already, I recommend watching the Collins–Bruford combination at work in the footage of Genesis playing Los Endos on the A Trick of the Tail tour in 1976.

Back to 2016 and Phil was putting his frailties on show for all to see. It reminded me of the first time I watched Queen’s These Are the Days of Our Lives video. And to choose Against All Odds – probably my favourite Collins solo song – a vocal he clearly could no longer do full justice to. A quick search brought up footage of interviews from 2016 – with Phil sometimes coming on to the TV set with a walking stick – to promote his new autobiography. He was open, honest – jaw-droppingly so at times – and didn’t pull any punches.

That’s why I picked up a copy of his book Not Dead Yet when I saw it in a charity shop. It was the end of 2019, a few months before the first Covid lockdown. Over the following two years I bought autobiographies by Steve Hackett and Mike Rutherford too. The rest of this blog is about those three books. To the best of my knowledge, Peter Gabriel and Tony Banks have not written anything autobiographical. I do have a second-hand but suspiciously pristine-looking copy of a biography of Peter (Without Frontiers: The Life and Music of Peter Gabriel by Daryl Easlea), but I doubt I will be turning to it any time soon. Although Peter is probably the most artistically creative and experimental member of the classic Genesis line-up (with Steve a close second, I would say), his musical journey is actually the one that interests me least.

Not Dead Yet by Phil Collins

One of the reasons I don’t read many autobiographies is because it is the author (the book’s subject) who is crafting this version of the story of their life – deliberately and purposefully shaping the narrative through their editorial decisions about what to include and what to omit – and you (the reader) who is under their control. That’s why I found myself immediately drawn to the put-it-all-out-there honesty of Not Dead Yet. If an author – Phil, in this case – writes about cheating on other halves (eg page 276 of the hardback edition: “I know that recounting this makes me sound like a right shallow bastard”) or alcoholism putting them at death’s door, they are unlikely to be lying about, sugar-coating or omitting other embarrassing or unflattering details of their life story.

I didn’t much like the 80s iteration of Phil Collins and, to be fair to Phil, I don’t think he does either. The Phil Collins who wrote Not Dead Yet is far more to my liking – chatty (you can imagine him saying much of this stuff in conversation), funny, self-deprecating and, above all, honest. Here’s one at random: we learn on page 136 that the lyrics of Invisible Touch, written in 1985–86 when he was married to his second wife, were actually about his first wife.

A couple of chapters are built around specific events – one is about how he almost got to play on a George Harrison solo album in 1970 – but on the whole it is a white-knuckle ride on the rollercoaster that was Phil’s life, especially once his solo career took off in the 80s and he became for a time one of the biggest pop stars on the planet.

We go from In the Air Tonight (his first solo single) to the Phil Collins Big Band via Live Aid and from Buster to Tarzan by way of Miami Vice. The main themes are work and family, and there is a lot – a lot – of husband-and-father stuff. If nothing else, reading Not Dead Yet will enable you to make your own mind up about whether Phil really is, as he says (on page 6) “a romantic who believes, hopes, that the union of marriage is something to cherish and last”.

But I read Not Dead Yet primarily for what Phil says about Genesis, so it was the how-we-made-this-album bits and the life-on-the-road anecdotes that interested me the most. In my simplistic view of things, I have always (and completely unfairly) blamed Phil for Genesis’s lurch to highly commercial, chart-chasing pop-rock in the 80s, so I was delighted that he doesn’t distance himself at all from classic Genesis – even agreeing that Supper’s Ready is the band’s magnum opus.

I got the distinct impression from reading the book that Phil was particularly close to Peter – before and after 1975 when Peter left the band – so it’s perhaps no surprise that, of all their output, it’s probably the Lamb album and tour that gets the most space, though, alas, the entirety of the ‘classic’ Genesis years – from Phil and Steve Hackett joining the band in 1970–71 to Steve leaving during the mixing of Seconds Out in 1977 – is covered in just 65 pages or so (out of a total of 400+ pages).

A Genesis in My Bed by Steve Hackett

These days I count myself as a huge fan of Steve’s solo work. I bought his (excellent) third album, Spectral Mornings, way back when it was first released in 1979, having been enchanted by the song Every Day. But I have only really got to know his solo stuff in the last few years, taking a chance on his 2017 album, The Night Siren, after which I picked up a cheap collection of five of his mid-career releases. His recent output – in terms of both quantity and quality – is phenomenal. In fact, unlike most late-in-their-career artists, he is currently producing the best music of his life.

Steve has always been adept at channelling the many and varied cultural experiences and insights arising from his worldwide travels into both his music and lyrics, ably assisted by his (now) wife Jo. However, though his albums are always lyrically interesting, he isn’t a natural wordsmith – which is partly what makes A Genesis in My Bed, published in 2020, an uncomfortable read, for this fan anyway.

And that’s a shame – because he has an interesting story to tell, one that frankly I was not expecting. Periods of drink, drugs, and darkness and depression – who would have thought it of the bloke sitting quietly and undemonstratively stage-right on those early Genesis tours, shielded behind the heavy-rimmed glasses, the thick, black beard and the dark clothes. Steve’s choice of book title – a reference to, well, that would be telling – is in itself revealing.

The writing isn’t dreadful. Here’s his description of the postwar London of his childhood, for example:

Crumbling pillars adorned sad facades, appearing ripe for slum clearance. Together those houses resembled rows of rotting teeth with the odd gaping black hole of a bombsite to completely ruin any semblance of a smile.

However, in all likelihood the book is more or less a DIY effort – and frankly it shows. We can forgive the occasional typo, tautology and other minor errors; I have yet to read a book that is completely error-free – and what I write certainly isn’t. It’s other stuff that is infuriating. The book cries out for a professional’s guiding hand. I can’t imagine for a moment that Steve would allow his music to be released without an appropriate level of quality control.

Aaaagh! Exclamation marks litter almost every page!!!

Aaaagh! Paragraph after paragraph ends with the dreaded three dots (ellipsis), like a ghastly case of measles…

And then there is the constant metaphor overload. Aaaagh! Take this run of sentences, for example:

A whole world of possibilities was revealing itself, starting as a trickle and becoming a flood. Once I’d opened Pandora’s Box there was no stopping me. During the tour, the ideas continued to germinate.

A good editor would also have helped organise the material: at one point he briefly covers the A Trick of the Tail period (an important moment, as it was the first album and tour without Peter), then moves on to Wind and Wuthering, and then returns to discussing A Trick of the Tail again.

I was certainly interested to read his account of his years in the band, his decision to leave and his ongoing relationship with Tony, Mike and Phil. Just like Phil, Steve clearly felt extremely close to Peter. The most barbed comment is aimed in Mike’s direction – he claims that in the 2014 Together and Apart BBC documentary Mike had asked for more focus on his own solo career at the expense of Steve’s – and he also makes clear that, though open to taking part in the 2007 reunion tour, an invite was never on the cards.

Another problem with the book is what is left out, relating to the years 1987 to 2007. We are informed in an afterword – presumably published only in the paperback edition and not in the original hardback – that his career “felt like swimming uphill and it was an emotionally traumatic period for me as well”. Why, then, write an autobiography, one wonders? There is much, we are told, that he was not allowed to write about for legal reasons…

The Living Years by Mike Rutherford

Mike’s book is the best of the three, certainly in terms of the writing. He is ex-public school, of course, so it’s reasonable to expect him to be able to string a few coherent sentences together. All three books are eminently readable and they all have good tales to tell but, compared with Steve’s book in particular, Mike’s writing is much more organised and controlled. Where Steve assails the reader with exclamation marks and ellipses, Mike is considerably more reserved and understated, his line in humour deadpan and dry.

This is typical. It’s a description of Island Studios where the band were recording The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway:

There were two studios: a nice big one upstairs and a cheap, depressing one downstairs with chocolate-brown shagpile on the walls. We weren’t upstairs.

Ironically, at the foot of that very page (page 148 of the paperback edition) Mike uses an ellipsis – “but at that point I decided I needed some time out…” – but in this case I would say it’s warranted. It’s a nice way to lead into whatever the some-time-out stuff was.

The book’s title is of course a reference to the Mike + the Mechanics song about the death of a father. It’s a title well chosen. Mike’s at times difficult relationship with his father – a senior naval officer – is a thread that runs through the whole book. Extracts from his father’s unpublished memoirs (he died in 1986 but they were only discovered after Mike’s mother’s death in 1992 and were much later presented to Mike in bound form by his sons as a Christmas present, presumably the trigger for him to write his own book) crop up regularly, often judiciously chosen as counterpoints to Mike’s own career.

I liked the honesty in the book. At times, he can be quite cutting, not least about Genesis members past and present (though it may equally well just be his sense of humour). To take just two of many examples, we learn that Steve didn’t pay Mike and Phil for their contributions to Steve’s first solo album, and that Tony will never have a hit single because he “never did understand how to make words flow”. In fact, there are numerous barbs about Tony, presumably because they have known each other so long. “I think to this day Tony thinks his voice is better than it is” is one. I assume they are all in-jokes.

One thing that annoys me about music biographies generally is that the material tends to be weighted towards the early years. Once the said performer(s) hit(s) the big time, the detail seems to thin out – as if it’s all in the public domain already or there isn’t really much of interest to tell. In Philip Norman’s Shout! The True Story of the Beatles we are told on page 178 of a 423-page book that Love Me Do (the first single) was released on 4 October 1962. We reach the first Smiths gig on page 149 of Johnny Rogan’s 303-page Morrissey & Marr: The Severed Alliance.

(Note also how stars seem far more willing to write about the early years of grinding poverty – I’ve paid my dues, to coin a phrase – than about the years of fabulous wealth. One minute it’s all battered vans to gigs and poky hotel rooms and the next we’re headlining Knebworth.)

Mike’s book is for the most part more balanced than many I have read, though he says surprisingly little about Foxtrot – a big breakthrough album for Genesis – and Wind and Wuthering, which, along with Selling England by the Pound (an album Mike doesn’t hold in as high a regard as I do) is probably my favourite Genesis album.

And then suddenly it all peters out. Thirty pages from the end of the book and we have reached the Invisible Touch album and tour in 1986–87. It’s the band at the peak of their worldwide popularity. It’s also when Mike’s father died, and so it’s the memoir’s natural end-point, given the way that Mike has crafted it. But real life doesn’t follow artificial story arcs.

We get a handful of pages about the 1992 We Can’t Dance period. A whopping two paragraphs about Phil’s decision to leave. Ditto the Calling All Stations period with Ray Wilson. Less than a page…really? Talk about damning with faint praise. A little bit (but not much) more than this about the 2007 Turn It On Again reunion tour. And, well, that’s it. A hugely anti-climactic feel at the end – not unlike the Abacab album, in fact, which finishes with the underwhelming and downbeat Another Record.

Some of the content above first appeared in a regular books, TV and films blog I wrote between 2020 and 2022.

No post found

Queen – The Miracle: Collector’s Edition

Was it all worth it? – It’s my favourite song from The Miracle and also a question I have been asking myself since The Miracle: Collector’s Edition landed with a veritable thud on the doorstep a couple of months ago.

The Miracle: Collector’s Edition is the latest Queen box set and comes thirty-three years after the album’s original release. The not inconsiderable sum of £150 buys you one vinyl album, five CDs, one BluRay, one DVD, one hardback book and assorted bits of memorabilia.

I should start by saying that if you want to read something that tells you that Queen are fabulous, this box set is fabulous, everything Queen do is fabulous, you may as well stop reading now. Yes, I think of myself as a fan – they have been my favourite group for more than forty years – but I still try for a bit of objectivity too. For more about that, see my review of Queen + Adam Lambert at Manchester in 2022.

I should also say that The Miracle has never been one of my favourite Queen albums. In fact, based on gut reaction, I once rated it my least favourite – more about that here. So when it comes to reissues and the like, The Miracle was far from the top of my wish list. (As I argue here, Live Killers is seriously overdue the super-duper all-you-can-eat treatment.)

I was, to be blunt, a bit underwhelmed when I first played the album, back in May 1989. Disappointed, even. Perhaps I was just expecting too much.

After the success of Live Aid and the Magic Tour, which elevated Queen to megastar status on a par with the likes of the Stones and Michael Jackson (in Europe at least), band activity suddenly ceased in August 1986 – despite what Brian had said publicly about plans to immediately either record new stuff or continue touring. (I am alluding to the interview that was used to open Channel 4’s broadcast of the Wembley concert in October 1986.)

Fast-forward to 1989. Publicity ahead of the album’s release – talk of a whole year in the studio, of batteries recharged and of old magic rediscovered – more than whetted the appetite, and the lead-off single certainly didn’t disappoint. I Want It All hinted at a back-to-basics approach but still delivered the anthemic sound of 80s Queen at their best. Body Language it wasn’t. And the B-side, Hang On In There, had a refreshing having-fun-in-the-studio first-take vibe to it.

As for the album itself, there was/is much to enjoy but also too much that is mediocre at best. In other words, it’s a typical 80s Queen album. Breakthru and Was It All Worth It? are two of the very best later-Queen songs, but Rain Must Fall and My Baby Does Me are two of the worst. Not awful. Just rather bland and pedestrian – not unlike Life Is Real (1982) and One Year of Love (1986). They should have been B-sides or twelve-inch fillers. Given the wealth of material the band were working on – perhaps, we are told, as many as thirty ideas/tracks – it is astonishing that both songs made the cut.

I like Khashoggi’s Ship and Scandal, but The Invisible Man sounds like a reject from The Cross’s debut album Shove It (in reality a Roger solo album) and was one of their weakest singles. And though Brian regularly cites it as a favourite, the album’s title track – and fifth single – is let down by premium-grade drivel like “That time will come / One day you’ll see / When we can all be friends”. Let’s face it, Queen were never great at writing lyrics about friends.

But my main reservation about the album – and indeed Queen’s 80s output more generally – is the use of synthesised drum and bass parts rather than natural instruments. Compare the timelessness of, say, A Night at the Opera to the dated sound of albums like The Works, A Kind of Magic and this one.

Take the opening track, Party – without doubt Queen’s worst album opener. It’s also the opening track on CD2 – The Miracle Sessions – but, unlike what ended up being released, this early version crackles with energy. At what point in the song’s development, you wonder, did someone suggest replacing Roger’s drumming with a drum machine. Ditto Breakthru – here with “real” bass and drums, to quote the liner notes.

I thought the work-in-progress CD from the 2017 News of the World box set was excellent, but The Miracle Sessions surpasses it. And it’s not just the previously unreleased tracks – intriguing though they are – that make it such a great listen. The alternative takes are in several cases radically different from – and in my opinion sometimes better than – what ended up on the Miracle album, in no small part because the band are playing live in the studio, Brian’s guitar is prominent in the mix, Roger is working up a sweat and, well, they’re rocking like it’s 1973 again.

CD2 includes five new songs plus A New Life Is Born, some of which is familiar as the opening to Breakthru. I like them all, particularly the two Brian tracks, You Know You Belong to Me and Water. The quality of these ‘new’ songs calls into question comments made after the release of the Made in Heaven album that the ‘vaults’ were now empty.

Anyone disappointed by Face It Alone is probably missing the point that they are listening to an unfinished track, an early sketch so to speak, something the band had chosen not to continue working on. Perhaps they couldn’t see a way forward with it at that point; perhaps they just thought it wasn’t good enough. As it happens, I think it’s not too bad at all – and I am glad they didn’t do further work on it now beyond cleaning it up for release. Yes, it is unfinished (most obviously the lyrics), but I like the downbeat and understated mood – not words normally used about Queen’s music and almost certainly not what most of the general public would have been expecting when it was released as a single.

CD2, then, is outstanding – but what else does £150 buy us?

Well, there’s a vinyl copy of the album. It is certainly a much more substantial product (it weighs 180 grams) than the thin, warped records we bought back in the good old days. Its quality reminds me of the Japanese imports that were so collectible in the late 70s and early 80s. (I gave away my vinyl collection more than a decade ago but my Japanese copy of the first Queen album is one of the few records I kept hold of.)

The packaging – including, for the first time, a gatefold sleeve – looks great. The big draw for collectors is the inclusion on side one of Too Much Love Will Kill You, Queen’s version of which first appeared on the post-Freddie Made in Heaven album. We can take the ‘long lost’ tag with a heaped spoonful of salt – Brian is particularly prone to hyperbole of this sort. The album was never ‘lost’ in any sort of literal sense. Too Much Love Will Kill You was pulled from the original release at the last minute because of a dispute about royalties (two outsiders were involved in the writing of it).

CD1 is the 2011 remaster of the album. No surprise there, but it would have been nice to have the additional track on this version of the album as well, if only for those of us who don’t own a record player.

CD3, meanwhile, is called Alternative Miracle, a rather hit and miss collection of non-album B-sides and extended remixes. The standout tracks are Hang On In There and My Life Has Been Saved – either or indeed both of which could and should have been included on the Miracle album itself. A different version of My Life Has Been Saved, originally the B-side of Scandal, appeared on the Made in Heaven album, but this is a better, more guitar-driven version of the song.

The extended remixes, on the other hand, are a bit of a letdown. Twelve-inch singles, with additional tracks and/or extended remixes, were an 80s thing, working best when they developed a song in a way that sounded natural and seamless – Back Chat, say, or I Want to Break Free (except for the hideous mashup at the end). The remixes of Breakthru and The Invisible Man, on the other hand, just sound like the producer experimenting with various effects after too much Southern Comfort.

Alternative Miracle also includes live versions of the older Queen songs Stone Cold Crazy and My Melancholy Blues. They were additional tracks on the fifth single, The Miracle, included to promote the (fairly dire) Rare Live video that was released at roughly the same time. It’s why Guitar World could get away with saying in the introduction to their interview feature with Brian that the box set includes “live cuts”.

There were no concerts, of course, for reasons we all now know, and so there are no live tracks to supplement the studio material.

CD4 – Miracu-mentals – is made up of instrumentals and backing tracks. That’s definitely one for fans only, I would suggest, as is CD5, which features two radio interviews, including the Queen for an Hour BBC interview with Mike Read that is already available elsewhere. Meanwhile, the DVD and BluRay discs are extremely disappointing. As with CD5, much (if not all) of the content is available elsewhere, and there just isn’t enough of it – videos for five singles and a few mini-documentaries. People on my favourite Queen message board who know a lot more than I do about the technical side of things are disappointed that the videos have not been fully upgraded (except apparently for I Want It All).

There’s also a hardback book. It’s all nice and glossy, as you would expect, but (again) there just isn’t enough content to fill 70-odd pages. The opening chapter tells us everything we need to know about the album and then we get chapters on each of the five videos. There are quotes aplenty, but you quickly realise that many of them come from either the DVD/BluRay content or the radio interviews.

The book that came with the News of the World box set is packed with great shots from their 1977–78 US and European tours. The Miracle book also has lots of photos – some of them, gosh, previously unseen – but they are mainly from the video shoots. Why not just watch the videos?!

The Scandal video on the DVD/BluRay exemplifies the problem. It’s obvious from the audio commentary (previously available on the Greatest Video Hits 2 DVD) that Scandal isn’t one of Roger’s favourites – either the song or the video. In fact, he is scathing about both. That’s fine when it’s one of seventeen songs, but less so when there are only five to watch – ie 20% of the total. Turn to the relevant chapter of the book and we find his less than gushing remarks reproduced there as well.

And so, is it in fact all worth it?

The answer perhaps depends on what you expect from a ‘collector’s edition’. To be fair, The Miracle: Collector’s Edition does what it suggests on the tin (well, box cover): it brings together in one place most if not all Miracle-related music and promotional products (including some postcards and posters and other bits and bobs that I haven’t mentioned) that a collector would presumably want to own. And as a massive, massive bonus it also contains some real gems – the work-in-progress stuff and the ‘new’ tracks.

But if the words ‘box set’ make you think primarily of previously unreleased material, The Miracle: Collector’s Edition is likely to leave you feeling underwhelmed, and you are probably better off (in more ways than one) settling for the ‘deluxe edition’ – ie CDs 1 and 2 – for roughly £20. Either that or stream it – Amazon Music has CDs 1–3 available but not the equivalent from the News of the World box set.

There is talk on the aforementioned Queen message board about doing something similar for the Innuendo album. If so, exactly the same problem will surely arise – the lack of previously unreleased material. If they are thinking of another box set – and judging by the sales figures for this kind of product that’s a big if – the case for making the next one Live Killers seems to me unanswerable.

No post found

Morrissey Live in 2002

This is a write-up of a Morrissey gig from twenty years ago. I unearthed it during a tidy-up of old newspaper cuttings and other music-related ephemera. I remember posting it on a fan website, presumably a day or two after the show itself.

I am obviously writing with my likely audience in mind – hence the hagiographic tone, the references to relatively unfamiliar album tracks and the general lack of objectivity. As a piece of criticism, then, it has zero value. But on a personal level it is a reminder of the only time I have ever been in the front row at a gig, and it is also perhaps of some interest for the insight it gives into the mindset of a (then) fan at a significant moment in Morrissey’s career.

We are back in 2002 – very much Morrissey’s wilderness years. He had released nothing since the not particularly well received Maladjusted album five years earlier. He still toured – I was there at a one-off gig at Battersea Power Station of all places in December 1997, when he played a Smiths song live for (I think) the first time as a solo artist (not counting the one-off free gig in Wolverhampton in 1988), and I saw him again (also in London) in 1999. I was vaguely aware that he was popular in other parts of the world, particularly Mexico, but it was hard to avoid the thought that – five years on and with no record deal in sight – his career was all but over, at least in Britain. Little man, what now? indeed.

There was also the self-imposed Californian exile – inexplicable in my eyes for someone I thought of as so quintessentially English. Hence the sense of relief that permeates the ‘review’ – yes, he’s still active; yes, Alain Whyte and Boz Boorer are still with him; and yes, he still obviously relishes the spotlight. There is more than a hint of nostalgia swirling around as well – emanating not least from the great man himself.

The gig itself was at Bradford on 31 October 2002. His big comeback was to be two years later, starting with the sold-out Elvis-flavoured birthday gig at the (then) MEN Arena in Manchester. My friend and fellow Morrissey fan Eddie and I went to three shows that year – all thoroughly enjoyable, but not quite on a level with this one two years earlier. After Bradford, it was never quite as good again, though a hot and sweaty Blackpool Winter Gardens in 2004 came close. We were at Liverpool Philharmonic Hall in 2006 and then at the Echo Arena in 2009 when he walked off midway through the second song and didn’t return. Neither did we. Ever.

It goes without saying that today’s Morrissey is not the inspiration I sprouted a quiff for all those years ago. I still buy his albums but that is as far as my loyalty stretches nowadays. Where once I found him delightfully cranky and contrarian, now he just strikes me as cold and cantankerous – not to mention gratuitously offensive at times. For Britain? Really? Enough said.

Morrissey, St George’s Hall, Bradford, 31 October 2002

Confession time: I’m a longtime fan of both Morrissey and Queen. Don’t try to work it out; I never have! Anyway, having watched Queen in concert more times than I care to mention, let’s just say that I’m used to being a football pitch away from the stage (literally so in 1982 and 1986). So, when I walked through the doors at Bradford, into the hall and then straight to the crash barrier, this was something new.

It was, for me, the most incredible, unforgettable experience. The pushing; the swaying; the jumping; the sweat! These were the riches for this poor lad. Conditioned over the years by common sense and then by advancing age to opt for the safe, sanitised experience, for once I could revel in the melee. Just as long as he doesn’t toss his shirt in my direction.

The chance to be so close to one’s idols. To look Alain squarely in the eye (I was to the right of the stage). To see him smile at a heckle from the crowd. To observe his guitar play. The messages he mouthed to his sound engineer. The slide he took from the mic stand and then tossed to the floor during Jack the Ripper. The foot pedals. The sweated brow. Now my heart was full.

I’ve seen the band on most tours since the Liverpool Empire in 91. To revisit Live in Dallas and a scratchy bootleg from Köln is to marvel at how much the band have both gelled and matured over the last decade or so. The leap in quality was already evident on Beethoven Was Deaf but now, as they hone their performance around the world, it is highly impressive. They appear so comfortable both on stage and with each other.

And what a joy to hear their reading of old Smiths songs. Apart from the Craig Gannon interlude (1986), these tunes never benefited from dual guitars on stage. It’s an absolute delight to hear those guitar melodies fully realised in live performance. To take just one example, I Want the One I Can’t Have came alive for me. So, I’m really pleased the lads took a bow at the end. Alain and a pleasantly portly Boz, in particular, are as much a part of ‘Morrissey’ as…well, Morrissey.

And what of the great man? My, how the between-song banter has developed over the years – along with the biceps but at the expense of the quiff, maybe. One or two remarks had me laughing aloud (“I Like You…this song is about me” – that may not be verbatim but you get the drift). And I love the subtle lyrical adaptations (“Come, pleeeze come, nuclear bomb!”) he introduces.

I also detected something new. There is evident bitterness (“Manchester bitches”) but there is also now a more openly expressed affection for the fans. You’ll protest that it was always there but, a few years ago, it might have been camouflaged by a quip (“I love you from the heart of my bottom…”) or expressed in a curt “I love you…I love you”. Now, there is less of the word-play. Now, it is up-front, full-on and heartfelt. Is there also a hint of self-parody? Is the decision to play Little Man, What Now? a gentle dig at himself as the years go by? Not to mention the inspired decision to introduce Hand in Glove to the set (“twenty years…twenty years!”). If I hadn’t downloaded the Birmingham set list, I might have expected to hear Papa Jack!

Morrissey at Bradford. The pleasure and the privilege was mine.

No post found

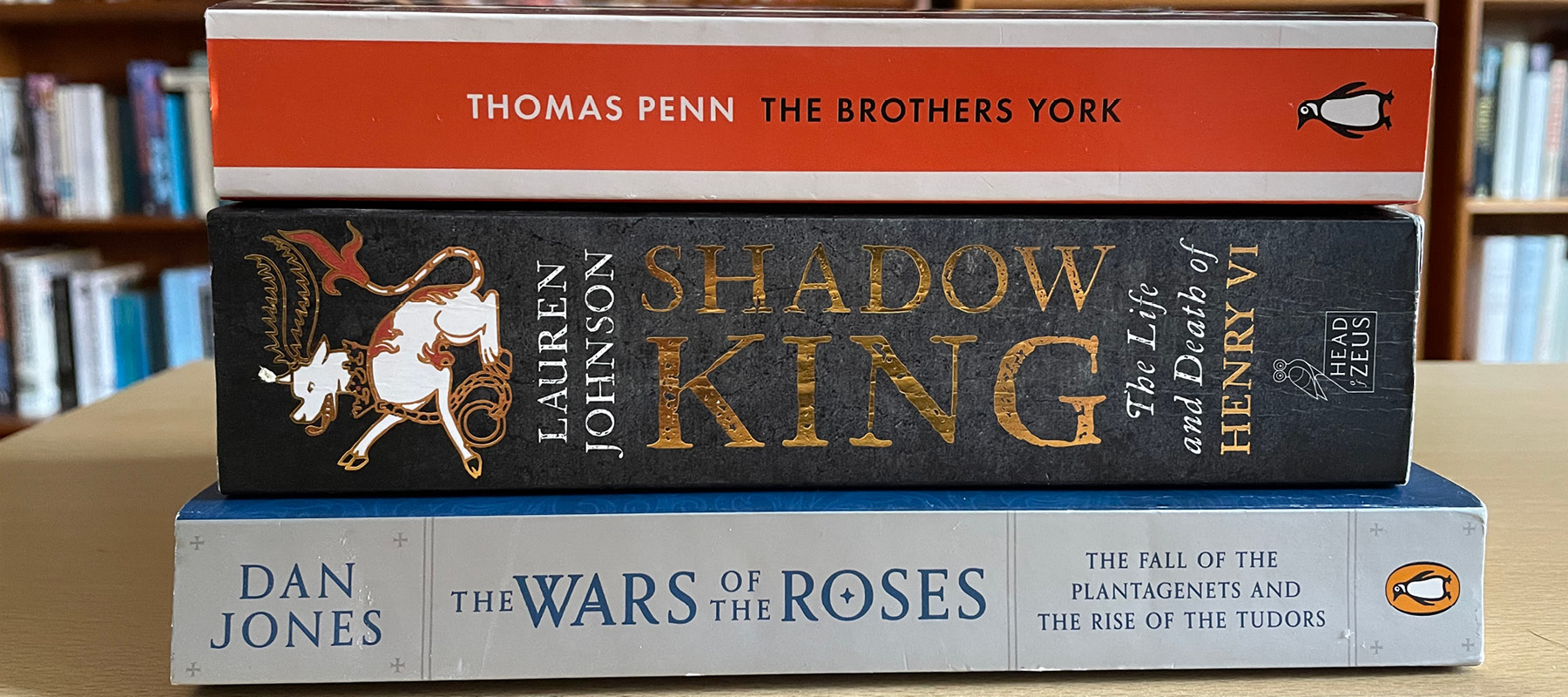

Henry VI and the Wars of the Roses

The past, it is proverbially said, is a foreign country. Perhaps it is, though in my case huge chunks of English history – the whole of the medieval and early modern periods, for example – were for a long time more like a far-off world than merely a place somewhere beyond the shores of Britain. As I admitted in my blog Enlightenment Now: Book Review, I plead guilty to half a lifetime of appalling narrow-mindedness. I have always thought of myself as a historian, but my focus for far too long was shockingly circumscribed – restricted to modern and contemporary history, and in fact nothing much beyond post-1900 high politics in Britain and Europe, war and international relations, and political ideologies.

That meant yes to the Russian Revolution and no to the agricultural revolution. Political diaries and memoirs were definitely in; medieval manorial rolls and church records were just as definitely out. I was up for a visit to the library to read copies of the New Statesman from August 1914 but not to a ruined castle to smell the history that surrounded me. I still recall the gentle rebuke from the head of the university’s history department when I requested a special dispensation to change the topic of my undergraduate dissertation: a proper historian doesn’t want to pick and choose, the professor (rightly) chided me.

Perhaps it came from our history diet at school, as hit and miss as the school meals they served us. As a kid, I wasn’t interested in either royalty or religion, but the vast bulk of what we were taught in class seemed to involve matters dynastic or religious. (I can’t remember ever studying anything post-Tudors until I was in sixth form, though we surely must have at least done the Industrial Revolution at some point.) Even simple family trees baffle me to this day, so it’s no great surprise that the tangled webs of family lineages, the rival dynastic claims and the flux of ever-shifting loyalties, so central to many of the narrative threads of the Middle Ages, left me cold.

Once I started to take studying seriously, I realised that I found history one of the easier subjects and I liked my teacher. O levels rewarded factual recall above everything: if memory serves, the history exam involved little more than regurgitating five pre-learned essays in two and a half hours. I had memorised whole extracts of Virgil’s Aeneid for the Latin exam so, yes, that was no problem. But was I properly engaging with the content? Did I fully understand what I was writing? Almost certainly not.

Times and tastes change – however slowly in my case. Ian Kershaw’s To Hell and Back, the first of his two-volume history of the twentieth century, sits on my bookshelf, as yet unread. I would have instantly devoured it a decade ago. Two more favourite historians of mine, Richard Overy and Anthony Beevor, both have major books out that in times gone by I would have picked up on day of release. I don’t as yet have either.

My favourite history read of the last year was probably Tom Holland’s Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind. It is the type of history I most look forward to reading nowadays. Holland is one of a group of historians — Dan Jones and Marc Morris are two others who immediately spring to mind — who regularly publish huge and hugely enjoyable histories that mix an engaging and accessible narrative writing style with excellent factual detail and knowledge of current research. Their work has done much to draw me to pre-modern history and to illuminate its highways and byways. And so too has historical fiction – though the exceptional books of the likes of Hilary Mantel, Kate Mosse and SJ Parris are well worth a blog of their own.

And so we come to the fifteenth century, a century that I have always steered well clear of (the Wars of the Roses in particular, another hangover from school days, I suspect). For anyone whose knowledge of the period is as sketchy as mine, I suppose the key point to grasp is the significance of the removal from the English throne – and subsequent murder – of Richard II, the last of the Plantagenets, in 1399. The usurper was Henry IV, the first of the Lancastrian kings.

The great upheavals of the following century ultimately come back to the question of legitimacy – the right to rule – ending not a little ironically with the rise to power of the Tudor dynasty whose claim to the throne was, in Dan Jones’ words, “somewhere between highly tenuous and non-existent”. Such a poor claim might go unchallenged in the event of strong and decisive leadership, but a monarch who appeared unfit for the role – indecisive, say, or militarily incompetent – would be in serious trouble. This was to be the fate of Henry VI.

Henry IV’s reign was plagued by rebellions and further destabilised by recurring illness. His son Henry V’s reign was highly successful in medieval terms – his reputation as an accomplished and personally courageous warrior-king immortalised by victory against the French at Agincourt in 1415 – but it was also disastrously (for the House of Lancaster) short: he died suddenly in 1422, leaving his son to become Henry VI at the age of just nine months.

A year or so ago I read a 2019 biography called Shadow King: The Life and Death of Henry VI by Lauren Johnson. It is well written and (importantly for me) user-friendly for the non-specialist. Johnson offers frequent reminders of who people are, their titles, former titles, familial connections etc, as well as a comprehensive Who’s Who as an appendix. The writing has an engaging narrative drive to it, with chapters typically ending on a cliffhanger.

My first impressions of Henry were of how unorthodox he was. As a king utterly out of step with the medieval view of monarchy, he seems to have had much more in common with Richard II (both Henry and Richard suffered the same fate, being deposed and murdered) than with his father, Henry V. In an age when ‘rules’ and codes of behaviour were all-important, it is no surprise that his actions (and inactions) caused such discombobulation.

Reading about the younger Henry’s unwillingness to follow the accepted rules put me in mind of President Woodrow Wilson and his doomed attempts to remake the international order at the end of the First World War by ditching the old system of power politics and alliances in favour of collective security and a League of Nations. There is also a parallel of sorts with President Trump, a blundering amateur who disregarded almost all foreign policy norms and conventions, believing that he could do personal deals that would solve age-old problems and end age-old rivalries. In reality, his meddling did more to stoke than to solve conflict.

Henry also resembled Richard II in displaying a fatal incompetence at crucial moments. For all that Henry’s mindset might not be out of place in the modern world, it was simply unacceptable in a medieval monarch. A man of honourable intentions, he was undermined by indecisiveness and an unwillingness to be sufficiently ruthless at key moments of his reign. He was deeply pious and equally deeply naïve. Time and again, for example, he chose to accept the solemn oaths and declarations of loyalty served up by his rivals, only to be later betrayed.

And despite being schooled in kingship from a young age, he came to depend on others, to the point that whoever controlled him controlled the kingdom — a recipe for calamity. Again, there is a parallel with the disastrous presidency of Trump: what to do when the top person is simply not up to the job. Henry VI was not just a poor decision-maker, he also suffered serious bouts of mental illness.

One thing I don’t particularly like about works of ‘popular history’ – notwithstanding the point above about narrative drive – is their tendency to stray worryingly close to ‘historical fiction’ territory. Well-researched novels that are set in the past complement history writing, but novel writing is a separate craft and the distinction between the two should not be blurred.

Take this, just one example from many in Johnson’s book, describing the loading of a ship with treasure at the port of Sandwich in 1432:

In the darkness of the harbour mouth, lights flashed and glared. Above the low creak of ships’ timbers, men’s voices punctured the frosty stillness of the night. Occasionally there came a low thump of coffers hitting the decking. A groan. A cricked back. And then the great chests lifted again, edged closer, step by heavy step, towards the tilting flank of a ship called Mary of Winchelsea.

Lauren Johnson, Shadow King: The Life and Death of Henry VI, from chapter 7

My first thought on reading that: how does the author know about the creaks and the groans and the low thumps, other than through guesswork? The footnote attached to the paragraph as a whole refers to a biography of Cardinal Beaufort (whose treasure it was) by GL Harriss and presumably relates to a fact Johnson gives us about the value of the cargo, Beaufort’s entire wealth.

And this is the opening sentence of Part IV of Dan Jones’ book on fifteenth century England:

The fourteen-year-old boy traveled through south Wales alongside his forty-year-old uncle and a band of loyal retainers, making their way toward unstable country, thick with woods and pocked with the turrets of glowering castles.

The rest of the page continues to refer to ‘the boy’ and ‘the man’. It is not until the following page that Henry Tudor and his uncle, Jasper, are identified by name. All very atmospheric but more the sort of thing I might expect to read in a work of fiction.

That apart (and I have no doubt many readers love such writing), Jones is an excellent guide through the maze of late-fifteenth century dynastic politics. His earlier book The Plantagenets (published in 2012) was an outstanding introduction to medieval English history and is high up my list of books to reread. I did not, however, find The Wars of the Roses as agreeable a read. The title itself is somewhat misleading, in my opinion. It turns out to be for the US edition – should Amazon (from whom I bought the book) make this more obvious? I was a bit miffed when I realised – hence spellings like ‘traveled’, ‘laborer’ and ‘ax’. In the UK the book was published as The Hollow Crown.

The events of the years 1461 to 1483 – the ‘dates’ of the Wars of the Roses that I memorised as a child – form only one section of the book, which opens in the 1420s and so covers much the same ground as the Lauren Johnson biography of Henry VI. It is this first half of the book – the period up to the deposition of Henry in 1461 – that is the better half. The rest by contrast, feels somewhat cursory. The reign of Edward IV is dealt with relatively briefly, especially the years after 1471 when he returned to the throne after the short second reign and then death of Henry VI.

Similarly, the author attempts to cover the rise of the Tudors and the consolidation of their power under Henry VIII in under a hundred pages. To be fair, Jones’ focus is very much on the attempt by the new dynasty to establish their version of history in the popular imagination – a story that ends in a united realm under the Tudor rose, naturally.

Next up for me in this area of history is The Brothers York by Thomas Penn. I very much enjoyed his book about Henry VII, Winter King. Penn is closer to the academic than the popular end of the history-writing continuum, which is fine by me as long as I have a reasonable foundational knowledge, and with a puff-quote from Hilary Mantel on the cover – “A gripping, sensational story” – what is there not to look forward to?

Some of the content above first appeared in a regular books, TV and films blog I wrote between 2020 and 2022.

The Thursday Murder Club

I am not normally a fan of ‘celebrity’ writers – or indeed celebrity much else. Football managers, for example, by which I mean former big-name players whose first or second managerial appointment is to a top club. There’s more than a whiff of unfairness in the air, a sense that their name brings with it massive breaks not available to ‘ordinary’ folk who may well be toiling in the background unnoticed for years and hoping against hope for something, anything, to happen.

There is certainly no shortage of celebrity writers, authors who are household names for something other than writing. Alan Titchmarsh, Fern Brittan, Graham Norton – to name but three, all of whom are well known from TV. Yes, I know I sound dismissive. No doubt their novels are enjoyed by millions. They might even be really good. They certainly sell well. But to what extent are the stratospheric sales – certainly of their first book – primarily a result of name recognition? That name alone is a precious commodity, enough to get the book a plum spot on one of the game-changing special-offers tables at the front of Waterstones, a headline in bookshops’ promotional emails and a place in the (shrinking) supermarket book aisles.

That’s why I shut my ears to the fanfare around The Thursday Murder Club, the first novel by Richard Osman, until I was charmed and disarmed by an interview in the paper promoting the follow-up. And yes, it is annoyingly good – as is the second in the series, The Man Who Died Twice, which I have just finished.

Annoying because… well, I have just explained why. But annoying for another reason too. The books hoodwink the reader into assuming that such an effortless read must have been equally effortless to write. It’s the same sleight-of-hand that lures us into thinking that writing for children must be – ahem – child’s play. And I do not find fiction effortless to write. In fact, I can’t do it at all. It’s frankly something of a relief, then, to read in the acknowledgements that Osman found the whole writing process bloody hard work.

You don’t need to be a master sleuth to spot the tell-tale signs of popular, page-turning crime fiction – the large, generously-spaced font, the bitesize chapters, usually ending with a mini-twist or cliffhanger, and so on. The stories are excellently structured and paced too. The plot doesn’t stand still for a moment, the short chapters offer us constantly shifting perspectives and the subplots bubble away. There’s no downtime to dwell on how ridiculous it all is (though I admit I found the pier scene in book two particularly far-fetched).

Osman’s writing is deliciously, unashamedly moreish. Opening either book is like settling down, glass in hand, in front of a roaring fire in the depths of winter. Granted, murder is the central plot device – including cold-blooded, gruesome executions – but the experience of reading The Thursday Murder Club and The Man Who Died Twice will still leave you feeling good about the world.

The setting – Coopers Chase, a luxury retirement village near to a fictional town called Fairhaven – could be somewhere in Midsomer, another fictional location populated by larger-than-life, cartoonish types and where you sense the sun is always shining. It’s that Midsomer-esque quality that helps make these books such delightful escapist fare.

Grim reality rarely intrudes. There’s no climate change, no cost-of-living crisis, no collapsing NHS. Instead, there are huge dollops of friendship, kindness and decency. The main characters all like and get on with each other. Police officers don’t childishly pull rank: Chris and Donna are best friends, even though one is a fifty-something DCI and the other a lowly constable learning the ropes before joining CID. Even the baddies have their soft side. Consider this exchange (in the second book) involving Frank Andrade Jr, a mafioso just arrived from the USA to kill the gangster Martin Lomax for ‘losing’ diamonds worth £20 million:

“Looks like I won’t have to kill you today, Martin!”

“Looks like it, Frank. How is your wife, did she get the muffins I sent?”

The trials and tribulations that come with older age can’t be completely ignored – one of the minor characters is slowly slipping away as a result of dementia, for example – and Osman certainly doesn’t shy away from gentle reflections on life’s Big Questions — family, love, loyalty, ageing, death.

But the overwhelming sense is that the members of the Thursday Murder Club are in rude health and having the time of their (long) lives. That’s perhaps another secret of the books’ appeal. Elizabeth, Ron, Joyce and Ibrahim are living out the senior years we all hope to enjoy – a time that is active, carefree, and enriched by companionship, not one impoverished by loneliness, lack of money or some unpleasant and debilitating condition or other.

And what of the four members of the Thursday Murder Club? Elizabeth apart, perhaps, there is nothing particularly remarkable about them, though in a Miss Marple kind of way their age is a sort of superpower, enabling them to ask, say and do things the police simply wouldn’t be able to.

Yes, they live secure and comfortable lives, but – to be fair – things have moved on a great deal from the “gentrified world of privilege and entitlement, of property and inherited wealth, of starched-collar formality and strict etiquette” that Agatha Christie described in her first Poirot novel a hundred or so years ago – a world I wrote about here.

We have strict gender balance, for starters. Former MI5 agent and unofficial leader Elizabeth provides the investigative skills and the knowhow when it comes to basic spycraft and dirty tricks. Joyce is a retired nurse, so handy to have at the scene of a dead body. She absorbs even the tiniest details around her but usually needs Elizabeth’s mind to fathom out the significance of what she has taken in. Regular extracts from Joyce’s gossipy diary offer a window into her world, her sometimes tense relationship with her daughter hinting at intergenerational family pressures that many readers will recognise.

Ron, meanwhile, is old school. He’s a loud, plain-speaking, West Ham-supporting ex-trade unionist who is warm and cuddly really but won’t – or doesn’t know how to – show it. Anyway, by book two he’s quietly and unobtrusively spending his nights on a camp bed by his mate Ibrahim’s hospital bed. Not, however, unobtrusively enough to escape Joyce’s notice; she later offers to drop off clean underwear, even though Ron’s manly attitude is “Honestly, no need.”

And there’s Ibrahim, the ex-psychiatrist with a sharply analytical mind. Like Ron, he is less prominent in book two. Mugged early in the proceedings, his recovery from his scars – mental as much as physical – is slow and painful. Here again is a hint at the reason for the books’ huge appeal. A subplot involving an assured and self-confident senior citizen who has the stuffing knocked out of them by some brush with mortality – an accident, a physical altercation – is one that will resonate with many of us.

Did I mention that the books are funny too – occasionally laugh-out-loud so. There are many, many great lines to enjoy. Here’s one of my favourites, a typical Joyce observation: “I’d welcome a burglar. It would be nice to have a visitor.”

And what’s not to like about writing like this, from the first book?

There had been a schism in the Cryptic Crossword Club. Colin Clemence’s weekly solving challenge had been won by Irene Dougherty for the third week running. Frank Carpenter had made an accusation of impropriety and the accusation had gained some momentum. The following day a profane crossword clue had been pinned to Colin Clemence’s door, and the moment he had solved it, all hell had broken loose.

The Thursday Murder Club is not a novel about Colin, Irene, Frank and the Cryptic Crossword Club. In fact, they are never mentioned again. But it typifies Osman’s style. One paragraph — 67 words — conveying so much information, and I don’t mean about crosswords.

The Thursday Murder Club did such a good job of reminding me of the joys of (well written) popular crime fiction that I made another impulse buy a couple of weeks later – A Line to Kill by Anthony Horowitz. I make a point of avoiding the back-cover blurbs of novels – I love setting off from page one with absolutely no idea of the direction of travel – but I am a sucker for a puff quote from someone I respect and admire. And what better recommendation than this from the marvellous Kate Mosse: “Witty, wry, clever, a fabulous detective story.” Okay, count me in.

Long before the end of the opening chapter it was clear that this was not a standalone novel, and not even the second in a series – it’s the third. Yikes. To quote Poirot: mille tonnerres! I have written often about how I always like to start any series from the very beginning. The first Poirot I read was The Mysterious Affair at Styles. My first (and so far only) Miss Marple was The Body in the Library, the first ‘proper’ one. I am also working through the Giordano Bruno novels by SJ Parris in order, starting with Heresy (I have already read one of the others, out of sequence, but I will go back to it when the time comes).

I was already familiar with the name Anthony Horowitz without quite being sure where from. The book itself reveals all – and I don’t mean on an introductory page. A Line to Kill is a bit like one of the those ‘alternate universe’ episodes (as the Americans say) from sci-fi series like Stargate-SG1 in which the characters and setting are similar to – but not quite the same as – the actual world. Or maybe it’s more like the TV series The Trip, where Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon play slightly exaggerated versions of themselves.

‘Anthony Horowitz’, then, is one of the book’s protagonists – a writer who has written a couple of true-crime books based on the work of ex-detective, private investigator and police consultant Daniel Hawthorne. Horowitz reminds us in passing that he wrote some episodes of Midsomer Murders and some (officially sanctioned) James Bond novels. Actually, he’s written much more besides, Wikipedia tells me, including plenty of stuff for television that I enjoy like Poirot and a long-forgotten detective/time-travelling mashup series from the late 90s called Crime Traveller, as well as [he adds, excitedly] two Sherlock Holmes novels.

And the verdict? Let’s just say that I now have The Word Is Murder (the first of the Hawthorne series) and Moonflower Murders in front of me, and I am hot on the trail of those Holmes novels.

Some of the content above first appeared in a regular books, TV and films blog I wrote between 2020 and 2022.

My First Album Buys

Ah, memory. You taunt and tease us. You fade and frustrate us. You even make things up and lie to us. What a shit you are.

This post overlaps with and follows loosely on from Radio blah blah: Records and record buying in 1977, my blog of what I was listening to and buying in the year I first caught the pop/rock bug. This follow-up differs in two ways: it focuses on albums rather than singles and I have extended the timeframe to 1979.

Compiling a list of first album buys was always going to be a trickier task than the singles equivalent. Most of the singles I bought were in the charts at the time, so scrolling through the Top 50s for 1977 made it easy to establish a fairly accurate chronology. Not so with albums. That’s because I rarely bought anything newly released, concentrating instead on standout albums from the few groups I knew and liked.

For years I took it for granted that I graduated to serious record collecting in 1978, the year I started to listen to rock music fairly regularly. Now I am not quite so sure. It’s like trying to guess the big picture from a handful of jigsaw pieces. I am trying to connect a few specific but disjointed memories to put together a timeline that fits.

Here’s one memory, for example: receiving Queen’s News of the World album as a Christmas present in 1977. [Click here for more Queen memories.] Another is of wasting money on not one but two dreadful Top of the Pops albums (cover versions of chart hits played by an in-house band of session musicians).

A third is of asking Santa for a K-Tel compilation album called Disco Fever (No 1 in the album charts in November 1977). Those compilations were better than their Top of the Pops equivalents in that they featured original versions of songs, though with early fade-outs to fit in more tracks. I have no idea why I was obsessed with Disco Fever – the likes of Baccara, the Floaters and Hot Chocolate – but I was, for five minutes at least.

There are a few more jigsaw pieces like those lying around – mental snapshots that linger. Taken together, they suggest that in 1978 I was actually spending what little money I had on watching Bolton Wanderers. Like all my friends, I was football-mad as a kid. My local team, Wigan Athletic, were non-league at the time and Bolton were doing well, promoted that year from the then second division to the first (ie the equivalent of the Premiership). The colossal sum of £2 covered bus and train fare, a ticket for the match and a programme.

Anyway, the landmarks I hope to glimpse on this meander down a fog-blanketed Memory Lane are those first few albums I collected. It will have been a gradual, haphazard, toe-in-the-water process, checking if I liked the temperature. There is some guesswork: I could add the word ‘probably’ or ‘possibly’ to most of the sentences that follow, and apologies in advance for overuse of phrases like ‘I think’ and ‘at about this time’.

There was an album of TV themes in the house pre-1977 but, other than my dad’s small collection of easy listening stuff (think James Last and weep), no rock music – that is, until my (older) brother started to buy albums, beginning with Rush, that he had heard in school. The first ‘proper’ album I held in my hands may well have been Elton John’s Greatest Hits which my dad borrowed from somebody at work, the first and only time I remember him doing so. There are few better openings to an album — albeit a best-of — than Your Song followed by Daniel. I taped it – the first songs I ever taped that weren’t ruined by the DJ’s jibber-jabber.

The first album I bought – well, that was bought for me – was Queen’s A Day at the Races, possibly in Llandudno (Wales) and probably during the bank holiday week in late-May 1977.

A Day at the Races was my introduction, aged 10, to grown-up, relatively uncommercial rock music. I played it endlessly for days, weeks, months. This album shaped who and what Queen were in my mind – and what to expect from an album – at an age when I was naturally highly impressionable. I literally had nothing else to go off for a while.

Everything about A Day at the Races oozed sophistication, from the elegance of the gatefold sleeve to the sumptuous smorgasbord of musical styles. Here, it seemed to me, were four dedicated musicians producing serious art, a world away from glittery show-offs singing vacuous pop songs and hamming it up on Top of the Pops. From the moment that needle met vinyl and the Escher-esque ascending scale faded into Tie Your Mother Down, I was hooked.

It took about four months to record, which translated as forever to a ten-year-old. I read a Brian May quote that a record would be around for ever, meaning that you had a responsibility to make it as good as you possibly could: his sentiment resonated precisely with what I was hearing and feeling. A Day at the Races created a benchmark of quality and style in my mind that I still find myself judging records by to this day.

The year 1978 arrives and the fog of memory thickens somewhat. I bought the remaining Queen albums, working backwards from A Night at the Opera (which has Bohemian Rhapsody on it), but was still mainly taping from the radio. I began listening to the Great Easton Express on Liverpool-based Radio City, an evening rock show presented by the DJ Phil Easton which broadcast once or twice a week. He even read out a letter I sent in. Dear Phil, I am twelve and I listen to the show every night. I’m Queen mad. Please play X, Y or Z by them (all album tracks as opposed to singles, if memory serves). He actually played something I didn’t ask for.

I also listened to Alan Freeman’s Saturday rock show, broadcast simultaneously on Radio 1 and Radio 2 (meaning it was in stereo) at 3pm. Actually, I listened to the opening five minutes, the bit when he read out who was on that week’s playlist. I was still far too immersed in football at that age to miss the latest scores coming in – not to mention bewildered by a lot of what he was playing (King Crimson, Jethro Tull and Emerson, Lake and Palmer the likely culprits).

We went on a school residential to a place called Hammarbank in the Lake District in July 1978. It had a record player in what must have been a common room, and we played a copy of 24 Carat Purple (a sort of Deep Purple best-of) to death in the evenings. I have no idea who it belonged to. We happily headbanged (‘freaking out’, we called it) to side two: Speed King from In Rock and two tracks from the Made in Japan live album, Smoke on the Water and Child in Time. 24 Carat Purple was an early buy – and by far the heaviest record (single or album) I had in my collection.

Another Hammarbank favourite was the live single Rosalie by Thin Lizzy, which was a big hit. Cue another snapshot – on holiday somewhere, and me and my brother being treated to an album each of our choice. He may have plumped for All the World’s a Stage by Rush. My pick was definitely Thin Lizzy’s Live and Dangerous – which makes it a post-Hammarbank memory, probably the summer holidays. I associate all my childhood holidays, Christmases and birthdays with double albums. The Song Remains the Same, Seconds Out, Made in Japan, Stage (a David Bowie live album), The Wall – all too expensive for me to afford, all bought for me as treats or presents.

Another one was a fairly obscure film soundtrack album called FM. The film itself bombed: I don’t think even the most obscure of cable channels has ever shown it. Almost certainly I wanted the soundtrack because it included We Will Rock You (a hefty two minutes out of 80 minutes of music). Looking back at the track list, it is still too ‘American’ for my taste — James Taylor, the Doobie Brothers, Steely Dan, Linda Ronstadt — but I immediately warmed to Life in the Fast Lane (the Eagles), Life’s Been Good (Joe Walsh) and the more chart-friendly Lido Shuffle by Boz Scaggs.

At some point in 1978, I think, the local British Legion started an under-18s disco on Mondays, and the DJ included a regular heavy rock slot. (The term ‘heavy metal’ for me means bands that came along a bit later like Iron Maiden and Saxon.) Every week was the same: Black Dog by Led Zeppelin, Paranoid by Black Sabbath and Let There Be Rock and Whole Lotta Rosie, two tracks from a just-released AC/DC live album. Black Betty by Ram Jam was another – a song I detested. Oddly enough I have never bought much Black Sabbath or AC/DC. Maybe I was just fed up of hearing the same tracks week after week. Of Led Zeppelin, on the other hand, more in a moment.

I first became aware of Genesis sometime in 1978 via a school friend who was mad about the song The Knife. It’s a nine-minute prog-rock classic from 1970 that went way over my head. But he also had their current album, And Then There Were Three. Its warmer sound was much more to my liking, particularly the single Follow You Follow Me (which plenty of fans of early Genesis hate). He gave me the album, presumably thinking himself too cool and sophisticated for the shorter, commercial stuff. (He also gave me his copy of Rainbow’s Long Live Rock ‘n’ Roll – the title track another Legion disco favourite, now I come to think of it.)

To my mind Genesis played ‘prog’ – progressive rock, a label I used for music that was typically long, adventurous and lyrically obscure but not guitar-dominated enough to fit in the ‘heavy rock’ category. As well as Rush, my brother was buying albums by Wishbone Ash and Budgie that didn’t appeal to me at the time (and still don’t). Another I didn’t much care for was Live Tapes by Barclay James Harvest, though I find it very listenable nowadays. The version of Rock ‘n’ Roll Star on there is a shoo-in for my (yet to be compiled) top-fifty-tracks-by-fifty-different-groups list.