Queen Live Killers: Forty-ish Years On

Essential listening in its day … Live Killers is flawed but brilliant nonetheless … Queen’s catalogue of restored and remastered live recordings currently contains a gaping pizza oven-shaped hole … The quality of the Rainbow ’74 box set, recorded five years earlier than Live Killers, presumably on significantly inferior equipment, demonstrates that analogue recordings from the ‘70s era can be cleaned up to an exceptional standard.

Diogenes

Queen played at the Dallas Convention Center in Texas on 28 October 1978, the opening night of what became their Jazz world tour, which came to an end fourteen months later with a concert in aid of Kampuchea at the Hammersmith Odeon in London.

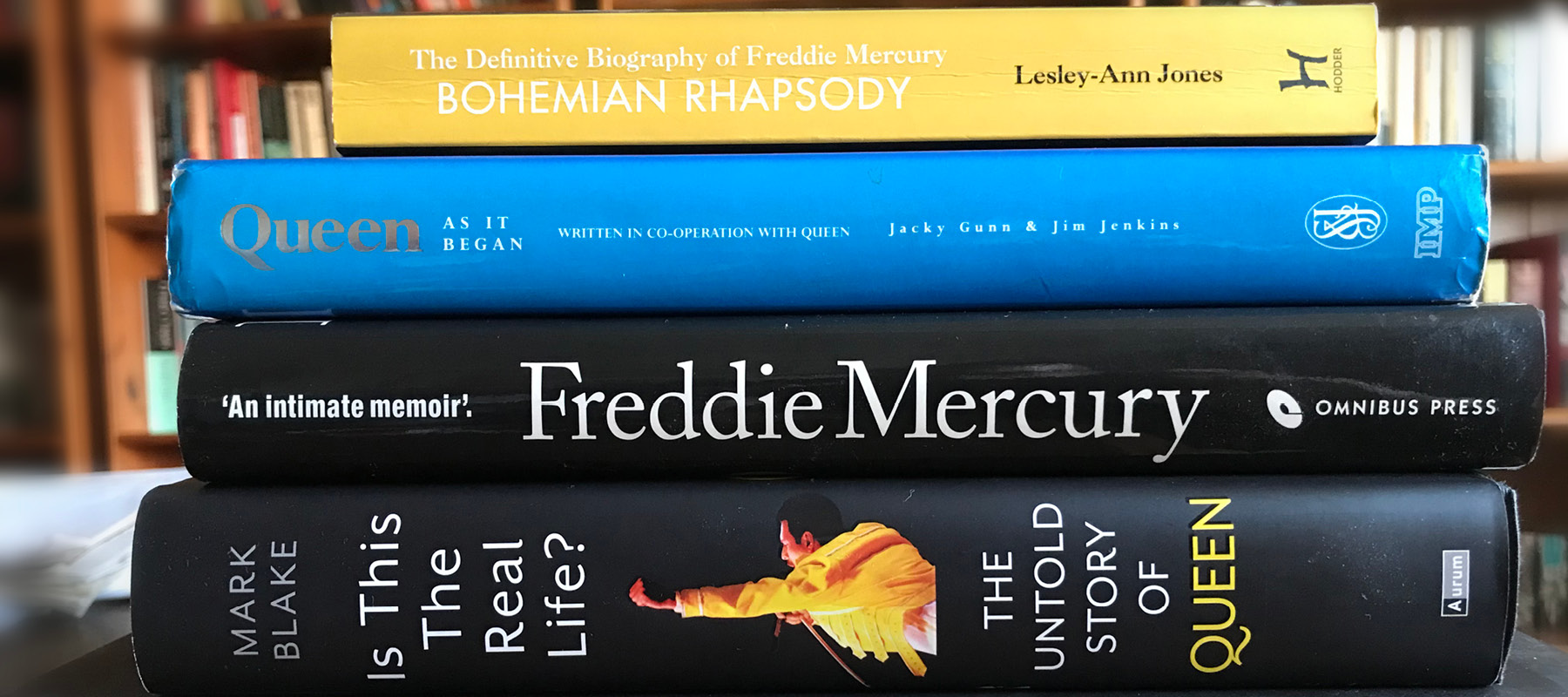

A photograph taken by Queen roadie and keen photographer Peter Hince, which is in his book, is interesting. It shows the magnificent ‘pizza oven’ roof of lights used on the tour. I originally wrote that the shot was taken either on the European or Japanese leg of the world tour, my thinking being that the American shows still featured the News of the World drum skin and the much later Crazy Tour of Britain used (a) fewer red and green lights in order to fit the rig into the smaller venues and (b) a different skin again — this time showing Roger’s face. The Mark Blake book Is This the Real Life: The Untold Story of Queen, however, states that the photo is in fact from the US tour, actually the opening venue in Dallas. Photos on the Queenlive.ca website confirm that the Jazz drum skin was indeed used at the Dallas show. Within a week at the latest, however, Roger had reverted to using the News of the World skin.

Recorded in continental Europe between January and March 1979, Live Killers is an album that I seldom play nowadays, preferring unofficial (bootleg) recordings, some of which are excellent, if obviously flawed in terms of sound quality. With the fortieth anniversary of its release approaching — and with fingers crossed for the appearance of some sort of retrospective late-’70s live package — this seems an opportune moment to re-join Queen on their 1979 European tour, to once again be “transported effortlessly from city to city” (to borrow from the Live Killers sleeve notes), and to evaluate afresh an album that captured the band at a transition-point in their career — before Mack and Munich, before ‘magic’ and ‘miracles’, before true global mega-stardom and mega-bucks.

In 1981, as a Queen-obsessed youngster, I wrote the following in one of many scrapbook ‘biographies’:

In fact, everything about this album is commendable, from the striking cover to the interesting sleeve notes to, of course, the music.

Many people seem to agree. It’s hardly scientific evidence but, as of August 2018, the Live Killers CD has a four-and-a-half-star rating on Amazon UK. Highly favourable write-ups can often be found in the publications (and websites) devoted to the ‘classic rock’ scene — Prog Rock, Planet Rock etc. A note of caution: with a middle-aged, nostalgia-hungry readership, it is clearly a matter of self-interest to wax lyrical about albums from this ‘golden’ era. Ultimate Classic Rock, for example, offered up this judgement on their website in 2015:

Live Killers was everything a Queen fan could ask for, the perfect memento from their breathless classic-era concerts – whether you got to see them in the flesh back then or not.

Ultimate Classic Rock (2015)

The whole piece reads in a similarly effusive way. But scroll back to the opening sentence — “Queen had long been known for their out-sized stadium rock shows”. Not true. This ‘review’ (and others like it) is laden with cliché and hyperbole. It is the Queen of legend, the stadium-bestriding giants of later folklore. The reality is that in the late-70s — pre-South America, pre-Live Aid, pre-Magic Tour — our heroes were still very much an indoor-arena band.

Judging from the more discerning reviews on Amazon and from various posts on fan forums, one recurring strain of thought seems to be that Live Killers slots into the decent-document-of-the-live-show-at-the-time category — in other words, nearly but not quite. Gary Graff, writing in Phil Sutcliffe’s excellent Ultimate Illustrated History book, unintentionally (I think) damns the album with faint praise, describing it as “solid and at times striking” [Phil Sutcliffe — Queen: The Ultimate Illustrated History of the Crown Kings of Rock, 2009 edition, page 257]. He’s writing, lest we forget, about arguably rock’s most compelling live act.

Live Killers has had a chequered history. It sold well, if not spectacularly, and some initial music press reviews, at least, were not entirely unfavourable. Its rawness and apparent lack of polish met with approval. Record Mirror described it as a “triumph”. Even Sounds awarded the album three stars out of five. (By way of context, Sounds awarded Jazz two stars and The Game just one star.) However, despite this and a number of grudgingly positive reviews of the subsequent Crazy Tour (of which a Mick Middles review in Sounds is a classic example), the music press remained almost uniformly hostile to the band. Punk and new wave might have burned themselves out by 1979–1980, but ska (urban, working-class, multicultural) and the ‘New Romantics’ (synthesised electronic pop, highly stylised fashion) were the coming Big Things. Queen were decidedly uncool.

In particular, Live Killers lived in the shadow of Thin Lizzy’s critically lauded Live and Dangerous, released a year earlier in 1978. There were certainly similarities: even the album’s title ‘Live Killers’ carried echoes of the earlier release. Criticism of Queen’s performance — the apparent bias towards their standout album, A Night at the Opera, and their newer material, the use of recorded tape during the show, the lengthy guitar and timpani solos — segued into familiar attacks on the band as pompous, self-indulgent and out of touch. Thin Lizzy, on the other hand, better suited the new wave aesthetic: street-wise outsiders with lyrics that romanticised rough, tough working-class culture.

Criticism also surfaced from within the Queen camp. The official fortieth-anniversary history states that the band were “under pressure to come up with a live album” [40 Years of Queen, 2011 edition, page 40]. Georg Purvis attributes feelings of frustration and dissatisfaction to all four band members [Georg Purvis — Queen: Complete Works, 2007 edition, page 49], though he supplies few, if any, dates and supporting references to provide meaningful context. Elsewhere, in comments attributed to 1983, Brian talks wearily of the inescapability of live albums. On Redbeard’s In the Studio ‘rockumentary’ show about The Game, both Roger and Brian are dismissive of the album. A 2001 remaster was well received but I can find no evidence of anyone suggesting it was a major improvement on the original mix. It was seemingly not deemed worthy of a reissue as part of the 2011 remasters package and, at the time of writing, it does not appear to be available in the official Queen online shop.

Everyone releases a live record. It’s just a filler before the next studio album. It will curb the sale of bootlegs sold at exorbitant prices. Such comments — all of them doubtless used at some point to justify the release of a live album — sound frankly un-Queen-like: the ‘uncompromising perfectionists’ meekly compromising to meet the expectations of others. This is hardly the obstinate, headstrong band whose debut single featured a drum solo, who released a six-minute single (seven minutes when Roy Thomas Baker gets carried away in telling the story) against unanimous industry advice and who, filled with unwavering self-belief, walked away from John Reid’s management in 1978 and into the Guinness Book of Records as Britain’s highest-paid directors.

Double (even triple) live albums were almost de rigueur at the time: Seconds Out, Strangers in the Night, Tokyo Tapes, to name just a few, all date from this period. Plans for a Queen live album had repeatedly been shelved during their early career. The bootleg often circulated as ‘Sheetkickers’ appears to be a professionally mixed 40-minute edit of the February ’74 Rainbow show. The November Rainbow shows were filmed, of course, as well as the 1977 Earls Court [Apostrophe or no apostrophe? See the Guardian newspaper’s style guide] shows.

Perhaps the feeling was that film would better capture the theatricality and visual power of the band. The 33-minute Queen at the Rainbow film was shown in cinemas in 1976, but without an accompanying audio soundtrack release. Once the home video market was established in the ’80s, We Will Rock You, Rock in Rio and Live in Budapest all appeared within the space of three years — none, however, with accompanying audio releases.

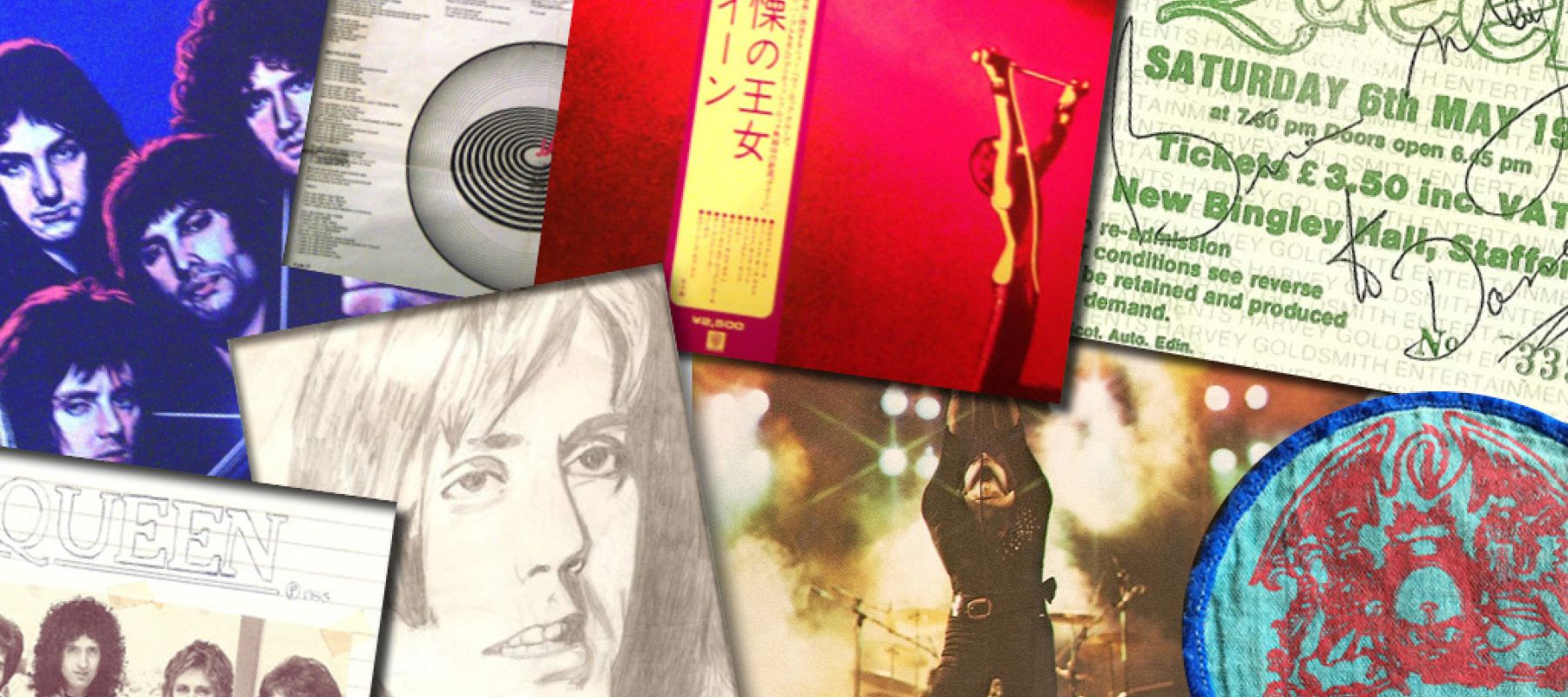

As evidenced on the excellent Queenlive.ca website and in Brian’s Queen in 3D book [Brian May — Queen in 3D, 2017 edition, page 136], the stunning front cover photograph is from one of the Japanese shows, subsequently manipulated to incorporate Brian into the shot. The original inner gatefold offered a busy montage of live shots drawn from across the band’s career, though (like the set list) leaning heavily towards recent tours. Impressive stuff.

Much less impressive, on the other hand, are the inner sleeve notes. Any useful context and insightful remarks are buried away beneath cliché (“literally fighting its way up the charts”), the occasional baffling statement (Keep Yourself Alive “having gone full circle over the years” — so when was it played significantly differently, one wonders?) and a sprinkling of sugary sentiment (“a very singable tune with sentiments never forgotten by Queen fans”).

It is misleading too, stating that Now I’m Here was “used as an encore and later dropped” on the News of the World tour. Well, it was dropped for perhaps a week. Check the Queenlive.ca notes for the Detroit show on 18 November 1977: the same website, however, lists it as having been played at Providence on 15 November and Philadelphia on 23 November, though my original 1995 edition of Greg Brooks’ Queen Live indicates not. Even Brooks has it back in the set by the Madison Square Garden show on 1 December. Brooks also omits Keep Yourself Alive from several of the December shows, including Houston on 11 December, when it was definitely played. It’s obviously a Brooks error.

From the single-minded foursome who supposedly almost wrecked the launch of Queen II by fussing over problems with the cover [An anecdote told by George Tremlett — Queen, 1976 edition, page 114], the egregious proofing errors — “eerieness”, “raport”, “his live album”, “form News of the World” — are particularly inexcusable.

Cue the thunderclap and the album begins at breakneck speed. The fast version of We Will Rock You, previously unavailable, is as exhilarating as when I first heard it at Stafford Bingley Hall in May 1978 and remains my favourite Queen set opener. Let Me Entertain You sits in its rightful place near the beginning of the show. It is baffling why this song was placed as the closing track on side one of Jazz. (Even more incongruous, though obviously unintentional, is its placing in the middle of thirteen tracks on the Jazz CD.) A six-song medley follows. End of side one: a chance to draw breath.

Side two leans heavily on audience participation, a quest for ‘authenticity’ that Roger was keen to emphasise in interviews at the time [For example, the Radio 1 interview with Richard Skinner on Queen On Air, CD 4, track 31]. Now I’m Here features Freddie’s call-and-response routine: a later staple of the show (‘Day-O’), it was new on the Jazz tour. The acoustic set slows the pace with its more laid-back, singalong feel. Brian’s guitar solo dominates the magnificent third side, though it’s a shame that Spread Your Wings features its conventional ending rather than the sensational, upbeat BBC session version. Side four brings the show to a close with the obligatory encores.

Given the limitations of space (four sides, approximately 22 minutes each), it is a varied and well-balanced package, relatively faithful to the actual set list running order. However, debate has always surrounded the omissions deemed necessary to fit the show onto four sides of vinyl. Three songs — If You Can’t Beat Them, Fat Bottomed Girls and It’s Late — were all ‘occasional’ rather than permanent fixtures of the set list over the fourteen-month world tour as a whole — played on some nights and not others, often alternated and usually the first to be dropped to make room for any new additions (for example, current single Don’t Stop Me Now was introduced on the European leg, Teo Torriatte was performed in Japan, and Mustapha, Crazy Little Thing Called Love and Save Me were all in the Crazy Tour set).

None of these ‘occasional’ songs were included on Live Killers. As a solid rather than exceptional track from the Jazz album, If You Can’t Beat Them is perhaps the least surprising, though the live version outshines the original. It’s Late was presumably left out on grounds of length. More surprising was the omission of Fat Bottomed Girls — recent single, inspiration for the Jazz promotional visuals and a full-throated stage rocker. The biggest shock, however, was the absence of Somebody to Love, again presumably due to its length — performed live, it lasted around seven minutes. Roger once commented that the band initially had difficulty translating the song to the stage. [Queen On Air, CD 4, track 31.] But it remained a live staple almost to the very end, a bona fide Queen classic. As an aside, I have always thought it deserved a place in the Live Aid set in place of Hammer to Fall.

The ever-evolving medley — not quite “play the Hits” [sic] as described in the sleeve notes — was another staple of the ‘70s show. Pacy and punchy, it featured snippets of singles and album tracks alike. Here, Roger’s vocal on I’m In Love With My Car and Brian’s harmonizer effects on Get Down Make Love are undoubted highlights. You’re My Best Friend, on the other hand, feels rather lightweight and out of place, though Queen fan, musician and YouTube reviewer James Rundle disagrees and singles it out for particular praise. It was dropped for the 1980 European tour.

Elsewhere, the Mustapha teaser at the beginning of side four is a pointless add-on — the reason for its presence being … what, exactly? Sounds magazine, among others, criticised the inclusion of the taped operatic section of Bohemian Rhapsody, also on side four. In this case, it is difficult to see how it could have been left out: as the 1986 Live Magic album demonstrated to nauseating effect, editing songs ends in disaster, and it would have been unthinkable to omit Bohemian Rhapsody altogether.

The inclusion of the entire three-song acoustic mini-set is also debatable. Only the Magic Tour, which also included a medley of rock ‘n’ roll standards, featured a longer acoustic interlude. Between 1980 and 1982, Love of My Life was the sole acoustic song, though the semi-acoustic Save Me featured earlier in the set. An obvious alternative would have been to omit Dreamer’s Ball and Brian’s long band introduction before ’39 (included, presumably, as light relief and to illustrate the exuberance of a typical Queen audience). As an aside, how ironic it seems to hear Brian referencing Roger’s tiger-skin trousers.

Based on the 1994 remaster track timings, the original four sides of vinyl add up to 22m 18s, 24m 52s, 22m 01s and 21m 08s respectively. Taking 25 minutes as the upper limit, an alternative track listing for the original vinyl release – restoring Keep Yourself Alive to its ‘correct’ place in the set – might have been:

Side One: We Will Rock You / Let Me Entertain You / If You Can’t Beat Them / Medley – omitting You’re My Best Friend

Side Two: Somebody to Love / Now I’m Here / Love of My Life / ‘39

Side Three: Don’t Stop Me Now / Spread Your Wings / Brighton Rock

Side Four: Keep Yourself Alive / Bohemian Rhapsody – omitting Mustapha / Tie Your Mother Down / Sheer Heart Attack / We Will Rock You / We Are the Champions / God Save the Queen

The poor quality of the overall sound is often highlighted — and rightly so. With a few notable exceptions such as I’m In Love With My Car — where the instruments seem separated out and clearer in the mix — much of the album sounds muddied and muffled, like listening through cotton buds rather than headphones. In Purvis’ opinion, “the band sounds muddled, some of the instruments are poorly mixed, and the audience levels are inconsistent” [Purvis, op. cit., page 49]. Imagine an album restored to the standard of the version of Sheer Heart Attack included in the News of the World box set [News of the World fortieth-anniversary box set, CD 3, track 13]: recorded at one of the Paris shows, it is genuinely raw, pulsating and anarchic.

The extent to which the tapes were tampered with during the mixing process is a matter of debate. Mark Blake describes Live Killers as “an undoctored account … loud and messy” [Mark Blake — Queen: Is This the Real Life?, 2010 edition, page 228]. Purvis quotes Brian as insisting “vehemently” that there were no overdubs [Purvis, op. cit., page 49]. Phil Sutcliffe’s book, on the other hand, quotes Roger that “only the bass drum was live” [Sutcliffe, op. cit., page 257] — speaking here, one assumes, with tongue firmly in cheek.

Given Queen’s reputation in the studio, this was never going to be a warts-‘n’-all release. Most — if not all — of the European shows were recorded, with songs selected from different nights. The website Queenlive.ca contains a brilliant track-by-track analysis, demonstrating that individual songs were often made up of recordings spliced together from different nights. I have neither a music producer’s ear nor a high-quality sound system. But even to this non-specialist, the change of ‘feel’ midway through songs and the ‘movement’ of instruments around the stereo mix were giant clues about the amount of general interference.

At times, the studio tampering is blatant. Why, for example, add an echo to Freddie’s introduction to Now I’m Here, recorded in Frankfurt on 2 February? The vocal at the beginning of Don’t Stop Me Now (up to “ecstasy”) has also almost certainly been added later. A tough song to sing, no doubt, and usually performed immediately after a frenetic and gruelling Now I’m Here, it was perhaps used as an opportunity for Freddie to catch his breath at the piano. The opening of the song was generally played with guitar substituting for the vocal. Of fourteen live recordings in my possession from 1979, the only exceptions to this are Newcastle (which includes three words: “Gonna have myself”) and the filmed Hammersmith show on Boxing Night, when he sang about half the opening lines, his voice being generally superb all evening after a four-day break.

Most controversial of all was probably the inclusion of bleeps to mask Freddie’s use of the word ‘motherfucker’ in his spoken introduction to Death on Two Legs. Again, one really has to wonder why this was included. Bizarre and wholly unnecessary, it could have been edited out or replaced with an alternative introduction during which he doesn’t swear. If it was an attempt at tongue-in-cheek humour, it failed utterly.

Equally extraordinary was the selection of Love of My Life as lead-off single, edging out Body Language in the most-bizarre-choice-of-first-single competition. From the band’s perspective, it obviously showcased the crowd-participation element of the show, as well as introducing a completely different side of their music to the general singles-buying public. This author has a vague recollection of Roger valiantly defending the single on a Radio 1 Roundtable review show. It sank without trace (in the UK at least), their worst chart performance since Keep Yourself Alive. The obvious choice should surely have been We Will Rock You (fast) — new, catchy and a perfect advert for the album. The frenetic version of Keep Yourself Alive — debut single, of course — might also have worked well, an appropriate way to bookend this phase of their career.

Essential listening in its day (it was, after all, the only live product officially available until 1984), Live Killers is flawed but brilliant nonetheless. The original tapes sit in the archives as well as the complete Paris footage, at least according to Brian [May, op. cit., page 149]. Queen’s catalogue of restored and remastered live recordings currently contains a gaping pizza oven-shaped hole. If there is to be some kind of re-release, it will almost certainly be an enhanced package, not just an improved version of the original Live Killers album. One hopes, naturally, for a complete, unadulterated document of the Jazz tour. Even allowing for Brian’s comments about persistent sound problems on the tour, the quality of the Rainbow ’74 box set, recorded five years earlier than Live Killers, presumably on significantly inferior equipment, demonstrates that analogue recordings from the ‘70s era can be cleaned up to an exceptional standard.

The wait goes on.

Great read, brought back some great memories.

The photo of the close of one of the shows is actually form Newcastle City Hall on Monday 3rd December.

I saw them the following night.

Cheers

Great read. The alternative tracklisting may very well have worked better. The omission of Somebody To Love has always baffled me.

I think that the beeped intro to Death On Two Legs may have been a legal safe guard. During 78/79 at some shows Freddie did say the song was about an ex manager. Most fans were aware, but maybe comiting “this song is about a motherfucker (of a gentleman)” to cellulose was just to much of a risk for EMI. I imagine if that’s the case, EMI would have wanted the intro removed but Freddie wouldn’t so I imagine we got a compromise.

I’ve seen many gigs through the years, but the Crazy Tour gigs are still some of my favourite ever shows.

Thanks for taking the time to respond – much appreciated.

I too have very fond memories of the Crazy Tour. At my first gig at Bingley Hall, I was very young and also stupidly didn’t take my glasses, so I saw very little. By Liverpool ’79, I was that bit older, the venue was smaller, and I wore my glasses! There was also a ton of stuff about them on TV and in the papers after years of virtual silence. It was a great time to keep a scrapbook!

As I say in the piece, I have neglected Live Killers somewhat over the years. It’s not my favourite Queen era music-wise (Jazz was certainly their weakest album up to that point, in my opinion) and I was always dissatisfied with the sound, especially after better sounding live stuff was issued. Going back to it – and that period generally – has been a real treat. Listening to recordings from the Jazz tours, they were really cooking on stage – though Freddie’s voice is shot by the end of some of the shows (especially the Japanese ones). And in its day, the ‘pizza oven’ was quite spectacular. What an album cover!

Great article, Darren – you’re an excellent writer.

I especially enjoyed your alternate track listing, which almost certainly would’ve been far superior. Points for keeping side 3 intact – it is perfect.

The “apparent bias towards newer material” bit is hilarious, and shows the hypocrisy of the press who were just out there to slag at will. The previous year the papers were slamming Queen’s shows for “relying on the on the golden oldies”. Queen just couldn’t win.

Thanks for taking the time to post, Bob.

As a young lad just getting into music, it was a depressing time to be a Queen fan. The music papers – Sounds, Melody Maker and NME – ignored them, except on the odd occasion when they wrote something horrible. I remember in Sounds the only mention of the American tour was to compare Freddie’s leather look unfavourably with that of Rob Halford of Judas Priest. That’s why the Sounds review of the live album came as quite a surprise!

I watched the Freddie Mercury Queen Tribute Wembley concert for AIDS awareness on the BBC this Christmas, advertised as broadcast on BBC Radio 1 FM, April 20th, 1992. I don’t follow the pop scene, but Queen are something else and the concert was excellent.