Books, TV and Films, February 2021

1 February

Age of Empire 1875–1914 is the final part of Eric Hobsbawm’s trilogy about what he called ‘the long nineteenth century’, beginning with the French Revolution in 1789 and ending with the outbreak of war in 1914. I bought this book at university when it was first published in 1987. It follows the same broad approach of the first two volumes, opening with a general economic survey, thus emphasising the centrality in Marxist thinking of economic developments to any understanding of history, before moving on to the social and political scene, culture and ideas etc.

One change, however, is a chapter specifically focusing on women. I remember Hobsbawm commenting on this in interviews at the time, an admission of sorts that the Marxist left had hitherto failed to give due weight to women’s struggle for equality in its historical and political analyses. This lacuna was one aspect of a more fundamental weakness. By the mid-1980s the traditional class-centric perspective was very much under threat from newer voices on the left who could see how capitalism was evolving — particularly the decline of the heavy industrial sector and the shift towards globalisation — and who were keen to embrace conceptions of identity based not just on the workplace but on gender, race and sexuality etc.

Their intellectual home was a remarkable magazine called Marxism Today which, despite retaining its old tagline ‘the theoretical and discussion journal of the Communist Party’, championed a radical new agenda at odds with the (very) old guard of the CPGB and their house newspaper, the Morning Star. Interviewees included the Labour leader Neil Kinnock and even the brash Tory politician Edwina Currie. Despite his seeming indifference to feminism, Eric Hobsbawn was one of the intellectual heavyweights influencing Marxism Today. Even before the election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979, he had given a seminal lecture called The Forward March of Labour Halted? which described how the traditional working class was fracturing.

3 February

The 2020 film The Invisible Man is a very up-to-the-minute take on the classic HG Wells story. The plot revolves around the idea often referred to as ‘gaslighting’, everybody’s favourite insult these days, especially when hurled in the direction of politicians. It is used to mean manipulating someone psychologically so that they end up doubting themselves and even, in extreme cases, reality and their own sanity. The film stars Elisabeth Moss, who seems to have achieved A-list celebrity status following her success in The Handmaid’s Tale, though I know her from twenty years ago as Zoe Bartlet, one of the president’s daughters in (probably) my all-time favourite series, The West Wing.

4 February

Speaking of people doubting reality and their own sanity, Marcella is one of the few drama series that I have watched in real time (as opposed to months or years after it was initially shown). Its central conceit — a highly capable police detective with extreme mental health issues — made for a compelling first series, though, inevitably, the follow-up stretched credibility up to and beyond breaking point.

It seems an age since series two was broadcast. Marcella is now in Northern Ireland, having been rescued from the streets by a shadowy police intelligence unit keen to make use of a talented officer officially registered as dead. I binge-watched the eight episodes over four days, enjoying the drama rather than worrying too much about implausible plot developments.

One wonders how the Maguire family, sufficiently sophisticated, ruthless and well connected to become the pre-eminent crime family in an area with a long and tragic history of troubles, manages to implode within a matter of weeks; or, indeed, why they would allow such a suspicious and manipulative character as ‘Keira’ to live in the family home, the nerve centre of operations, when they clearly have no compunction about bumping off anyone who seems to threaten their status.

Fellow ex-Brookside regular Amanda Burton joins Anna Friel in the cast. Amanda was a primetime regular in Silent Witness in the ’90s but I remember her as the middle-class Heather when Brookside first started in the ’80s. Her performance in the final two episodes of Marcella, following a significant plot twist, is the acting highlight of the series.

10 February

The Odessa File (starring a very young-looking Jon Voight) is one of those ‘classics’ — like Ice Station Zebra and The Heroes of Telemark, both of which I watched recently — that pop up fairly regularly on television, usually on a Saturday or Sunday afternoon. The film is overlong and underwhelming but it’s the novel that I remember, written by Frederick Forsyth, who made his name with the thriller The Day of the Jackal. I read both books probably as a sixth-former, just becoming aware of page-turning novels as an enjoyable way to learn about historical events. Alistair MacLean and Jack Higgins were other writers I read a lot — books like Partisans and The Eagle Has Landed, both set during the Second World War.

12 February

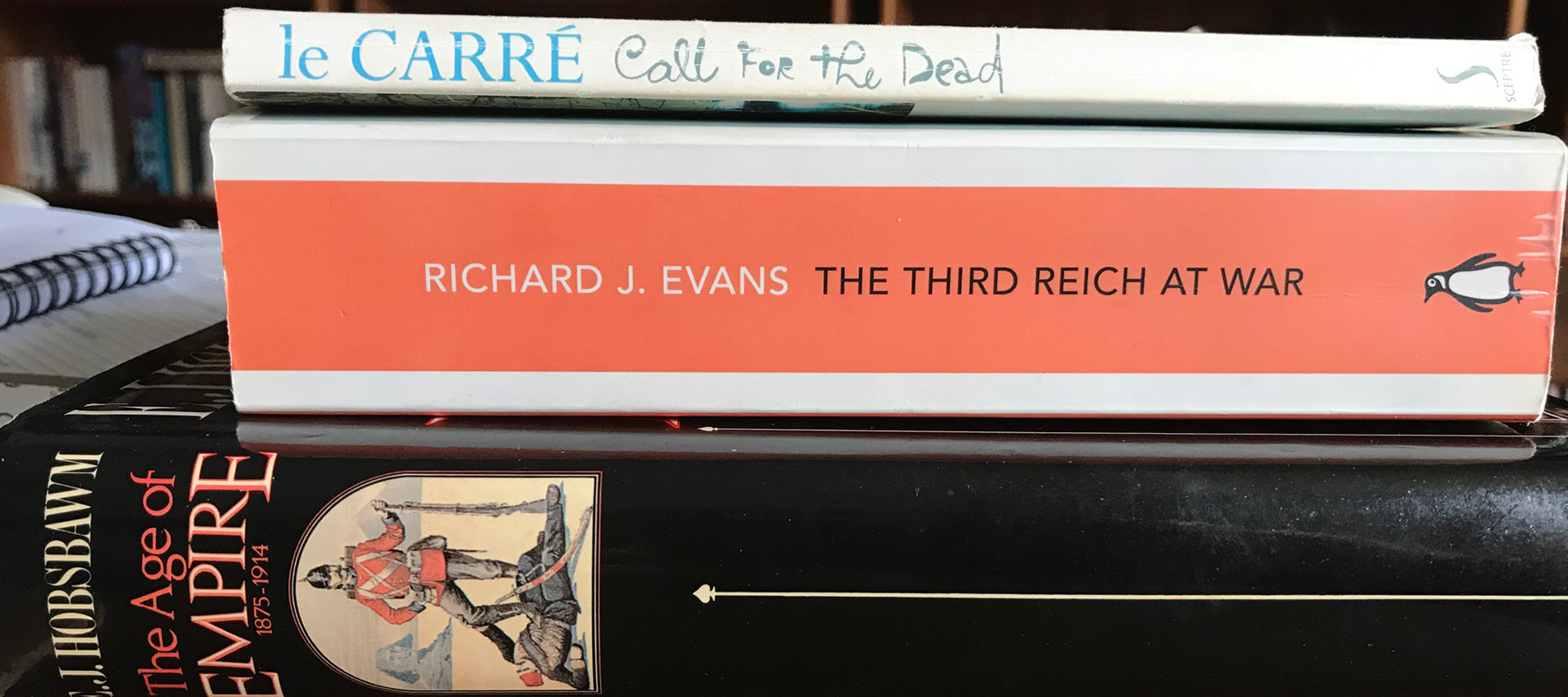

“Short, fat, and of a quiet disposition, he appeared to spend a lot of money on really bad clothes, which hung about his squat frame like skin on a shrunken toad.” This description appears on page 1 of Call for the Dead, the first chapter of which is entitled A Brief History of George Smiley. It was John le Carré’s first novel, published in 1961. The announcement of his death seems as good an excuse as any to read more le Carré.

For some reason I was under the impression that Smiley is only a fleeting presence in this first novel; he is, in fact, its central character. Le Carré didn’t start writing full-time until after the huge success of his third novel, The Spy Who Came In from the Cold; in Call for the Dead he is still finding his way and perhaps reveals a little too much. What I liked so much about Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and Smiley’s People was their depiction of an inscrutable, enigmatic Smiley, at home in the shadowy world of espionage.

13 February

The film Lady Macbeth reminded me of Fanny Lye Deliver’d. Both are good low-budget productions, both are set during key moments in England’s past — the Industrial Revolution and the period of Cromwellian rule respectively — and both explore class and gender relations in times when society was rigidly hierarchical and patriarchal. The main difference is that, in the case of Lady Macbeth, I gradually lost my initial sympathy for the female lead, who is locked (almost literally) in a loveless household with her weak, drink-sodden husband and his dour and domineering father. The clue was in the title, I guess.

14 February

A few years ago the art historian and TV regular Janina Ramirez promoted her BBC Four documentary England’s Reformation: Three Books That Changed a Nation by encouraging her Twitter followers to post pictures of the three books that have most influenced them. I chose The Weirdstone of Brisingamen by Alan Garner, the first book I remember being read to my class at school, when I was about eight; the Complete Sherlock Holmes, which got me through a not very enjoyable school exchange visit to France when I was fourteen; and Hitler: A Study in Tyranny by Alan Bullock, the first full-length history book I read, when I was a sixth-former.

I have been tempted recently to re-read either the Hitler biography — a true classic — or Bullock’s later Parallel Lives, a joint biography of Hitler and Stalin. Both, however, are huge books and I need to read The Third Reich at War, the final part of Richard J Evans’s Nazi Germany trilogy.

20 February

Two more films.

The Rhythm Section starts promisingly. Stephanie is a bright young woman whose life has fallen apart after all her family were killed in a plane crash; we later find out that she should have been on the plane as well and that they were only on that particular flight because of her. An investigative journalist tracks her down to a brothel and reveals that the crash was actually the result of a terrorist bomb. Unfortunately, The Rhythm Section starts to lose its rhythm at this point. Stephanie locates a ruthless and highly secretive ‘off-the-grid’ MI6 agent by typing a postcode into Google Maps. He then trains her to impersonate a dead assassin and soon she is commanding $2 million per hit. Villanelle in Killing Eve does it all with a lot more panache.

I realised after about 20 minutes that I have already seen Child 44, a film about a hunt for a child killer. The selling point (for me) is that it is set in the old Soviet Union, predominantly in 1953 (the year that Stalin died). The film’s hook is that, as the party line was that murder (or indeed any crime) was a capitalist disease and therefore impossible in the socialist paradise, to even conduct a serial-killer investigation was potentially a treasonous act.

It is too simplistic to say that the Stalinist state tried to somehow abolish crime. What was common was criminal behaviour explained away as the result of mental illness or counter-revolutionary activity. Some have also criticised the stodginess of the film and particularly the Russian accents. I found it a convincing depiction of a workers’ anti-paradise in which state power had grown to monstrous proportions, ordinary working people lived lives of fear, often in conditions of abject squalor, and the most active and ruthless criminal of all was the state itself.

26 February

Imagine being a rock music fan just discovering Led Zeppelin or Deep Purple. One of the benefits of never having been a telly addict is that I get to pick and choose from an inexhaustible supply of seriously good programmes from years gone by. The police cold-case drama Unforgotten, for example. Based on the lavish praise heaped on it ahead of the new series, I decided to give it a go. And it is terrific. Each episode is about 45 minutes long. I watched almost a complete series in one Friday evening binge.

They’re up to series four. I can access series two and three from ITV Hub but series one is currently only available via Netflix (which I would have to pay for). That seems annoyingly arbitrary. If ITV are promoting past series of a currently running drama via their on-demand platform, it surely makes sense to make the whole thing available.

So, series two it is. Fortunately, there is no story arc overhanging from the first series. I immediately warmed to the two central characters, DCI Stuart and DI Khan. It’s their ordinariness — the lack of glamour, the absence of power politics, their basic decency and humanity. How refreshing to see them working as a team and treating colleagues with respect, rather than endlessly pulling rank, shouting at subordinates and flying off the handle when an investigation doesn’t go exactly to plan or yield instant results.

28 February

The Third Reich at War has reached 1945. It is still impossible to read about the Second World War without feeling sickened by the enormity of what took place, particularly in eastern Europe — the wanton destruction, the sadistic cruelty, the mass slaughter. Much of it (though not all) was carried out in the name of Germany and, as Richard Evans makes clear, perpetrated by regular soldiers as well as by fanatical Nazis, though to nothing like the same extent. And as Evans also points out, it is inconceivable that millions of ordinary Germans back home were unaware of what was happening, at least in broad terms, once the systematic extermination of the Jews was underway.

The savagery began not with the death camps but as soon as the German army invaded Poland in September 1939 — looting, burning and pillaging, large-scale summary executions, mass killings and so on, carried out not just against Jews but against all those the Nazis deemed inferior. And yet Hitler was never more popular in Germany than in 1940. How quickly and easily a civilised nation, drunk on victory and seduced by lies, had succumbed to barbarism.

In 1943, according to Evans, the Luftwaffe general Adolf Galland reported to Hermann Goering (in overall charge of the Luftwaffe) that he had proof from shot-down pilots and plane debris in Aachen that the Americans had managed to develop fighter planes with added-on fuel tanks, increasing their range. This meant that fighters would now be able to escort bomber planes further into Europe, thus increasing the devastation to Germany’s cities. Goering, who had boasted at the start of the war that not a single enemy bomb would fall on Germany, replied: “I herewith give you an official order that they weren’t there!”

On 6 March 2021, footage circulated on Twitter with the caption: ‘Parents encouraging kids to burn masks on Idaho Capitol steps’. This may or may not be an isolated incident, but there is no doubt that we are once again living in the West in an age when cranks, firebrands and demagogues are no longer on the forgotten fringes but part of mainstream political debate. Millions of people are again prepared to follow leaders who have little or no regard for science, objective truth and reasoned argument; who attack the pillars of an open, just and tolerant society such as free and fair elections, an independent judiciary and investigative journalism; and who peddle conspiracy theories and preach bigotry and intolerance.