Books, TV and Films, December 2020

1 December

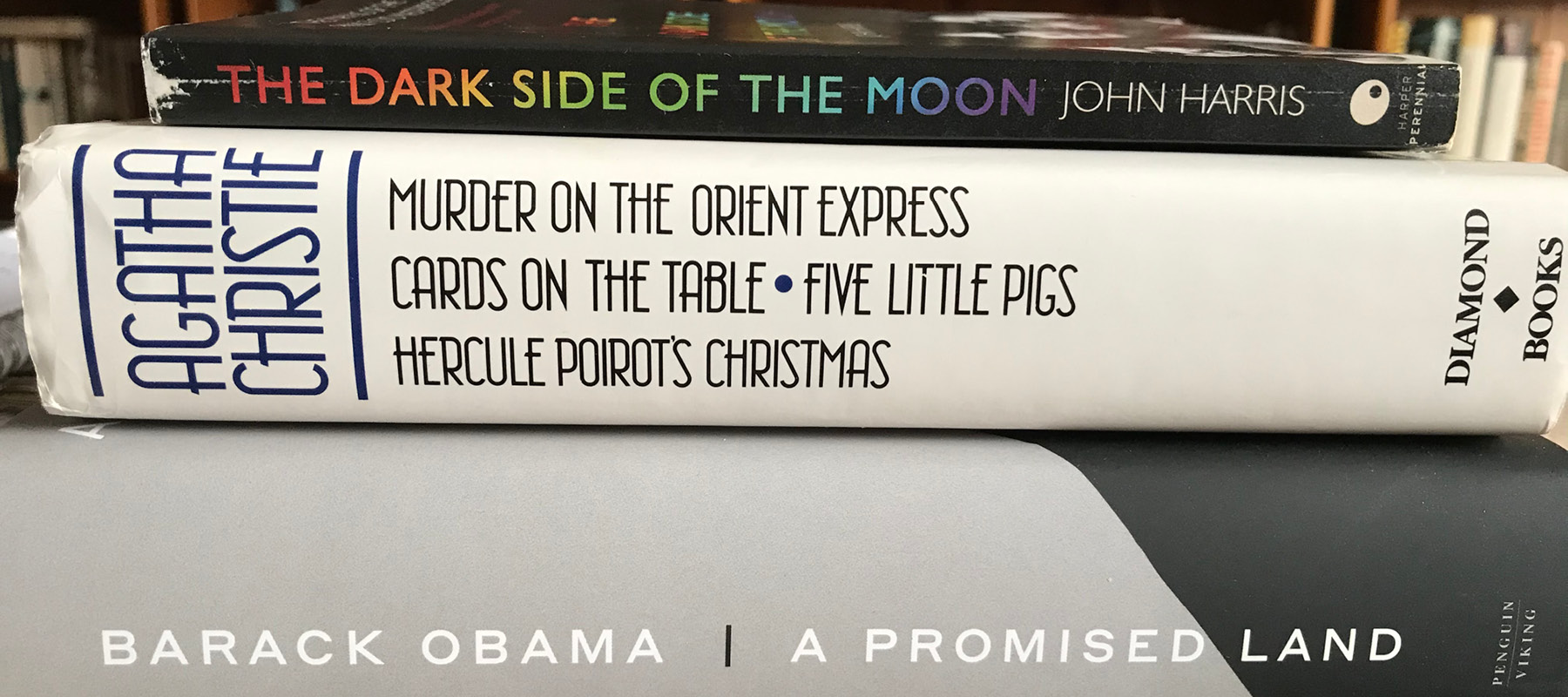

Straight in at Number One on my reading list goes A Promised Land, the first volume of Barack Obama’s memoirs. Just a quick word on the cover price — a wallet-busting £35 (selling at half price in Asda). It’s said that the Obamas negotiated a book deal in the tens of millions of dollars. Michelle Obama’s book, Becoming, was a worldwide bestseller. I am sure that the publishers are expecting something similar from A Promised Land, but, even for a volume running to 700-plus pages, the cover price is seriously off the charts.

3 December

The Homesman is a remarkable film. Set in the 1850s, it shows the harsh, bleak reality of the American West and the meaning of rugged individualism. I suppose it might be called ‘revisionist’. It is certainly nothing like the sanitised westerns on which my generation grew up.

At the centre is a compelling character called Mary Bea Cuddy, played beautifully by Hilary Swank. An intelligent, hard-working, pious and fiercely independent woman, she volunteers to undertake a long and dangerous journey to transport three mentally ill women to a place of refuge. She longs to find a man to marry, only to be rebuffed as plain and bossy when she raises it with a potential (though, frankly, unsuitable) candidate. To hear her repeat almost the exact-same proposal to a second, equally unsuitable, individual later in the film is heartbreaking.

8 December

I picked up the Obama book not knowing quite what to expect. I was aware that he has published other books, and so I was unsure how much of a ‘Life’ A Promised Land would be. The answer is: not much. There are details about his childhood and early adulthood, including Harvard Law School, and his time as a state senator in Illinois and then a US senator, but it is all somewhat sketchy. By page 80 he is running for the presidency.

The themes are there almost from the off — change, hope, unity across the divides, building a grassroots campaign. For those of us on the moderate progressive wing of politics, Obama is surely the most inspiring leader of the last generation. At a moment when the nightmare of Trump’s presidency finally appears to be all but over, reading Obama’s beautifully written account of his rise to power is to be filled again with a rush of optimism and hope for the coming decade.

At the same time the book leaves a lingering sense of uneasiness. Democracy in the USA has — barely — survived the stress test of the 2020 election. Probably. Possibly. It is worth remembering that one of the candidates went to court to try and nullify the legitimately cast votes of millions of US citizens, a tactic that was supported and applauded by millions of other American citizens. As parts one and two of the Obama book remind us, the USA is in almost permanent election mode, lawyers are as indispensable as campaign volunteers and any serious candidate needs to raise millions of dollars just to get a seat at the table. Politicians are in effect beholden to vested interests, wheeler-dealers and power-brokers. It is a strange notion of what democracy means.

17 December

It looks like volume one of Obama’s memoirs is going to close with the killing of Osama bin Laden in 2011, a few months after the disastrous (from the Democrats’ perspective) midterm elections. Obama is as eloquent on the page as he is in front of a microphone — I have no trouble believing that these 700 pages are entirely his own work — but what really sets these memoirs apart for me is their frankness.

Obama is open about the strains that his chosen career placed on his marriage and unforgiving in his assessments — of himself, his colleagues, his opponents and others whose paths he crossed on the domestic and world stage. As well as the fine words and the high-flying rhetoric, there is also Obama the everyman. The pages are peppered with profanities, and it is clear that his younger days revolved around playing and watching sports, drinking beer and attempts to “get laid” — his phrase.

It’s easy to see why his original plan for a one-volume, 500-page effort was quickly revised. Every issue — from healthcare to Middle Eastern politics — begins with a page or two of background before we learn in detail about what was discussed, who said what and who did (or didn’t do) what. We get pen portraits of prominent people he meets. Some of his assessments — for example of President Sarkozy of France — are less than flattering. These sketches generally follow a template, even down to commenting on hairstyles. Take this example, about Benjamin Netanyahu:

Built like a linebacker, with a square jaw, broad features, and a gray comb-over…

A Promised Land, Barack Obama, p630

For British readers there are some inevitable Americanisms to navigate — ‘gotten’, ‘swiftboated’, ‘the Queen of England’ — as well as Obama’s annoying habit of referring to people as ‘folks’. Occasionally, too, he lapses into campaign-speech mode — money, for example, is usually rendered as ‘tax dollars’ and at one point he even questions how willing Europe’s wealthier nations would be to see their tax dollars redistributed to people in other countries. Oops.

On the whole, however, he is an eloquent champion of progressive politics, the merits of gradualism and rational over irrational thought. Though he is usually content to explain away the many attacks he faced as the rough and tumble of politics, his anger and outrage at unacceptable behaviour sometimes announce themselves — for example in his description of a hurriedly arranged meeting with the CEOs of leading banks and financial institutions, who were happily pocketing massive bonuses in the wake of the 2008 financial meltdown, despite the government having committed eye-watering sums of money to prop up the financial system.

19 December

A short piece in yesterday’s Guardian on comfort reads at Christmas suggested Hercule Poirot’s Christmas — exactly the book I had opened earlier that morning, though more for something light after my last two heavyweight reads. It’s my third Poirot and the first not to feature Captain Hastings as narrator. Instead, Agatha Christie conjures up the most hilariously unlikely dialogue between loved ones as a way of conveying scene-setting information:

Why my brother George ever married a girl twenty years younger than himself I can’t think! George was always a fool!

Alfred Lee to his wife, Lydia

20 December

From comfort reads to comfort viewing. This morning I watched the first episode of the reboot of All Creatures Great and Small. The original TV series with Christopher Timothy, Robert Hardy and Peter Davison was a staple of the eighties, of course. I wasn’t an avid watcher but the characters, the scenery and the music are unforgettable. I also have copies of the first four Herriot books in two omnibuses, All Creatures Great and Small and All Things Bright and Beautiful.

I must admit that I hesitated before recording this new iteration. The six episodes have been sitting in the My Recordings folder since they were first broadcast. I am not a fan of Channel 5, though I read that they are now investing heavily in more serious programming. Anyway, if the first episode is typical, I am glad I did. It’s beautifully done, doesn’t cut any obvious corners and, of course, the scenery is breathtaking.

22 December

Another short read — the story of the making of The Dark Side of the Moon by Pink Floyd. The book is written by Guardian journalist John Harris. I picked up the book itself a few years ago when HMV shops weren’t an endangered species on the high street, an impulse buy from a selection on display beside the sales aisle — a temptation I normally try to resist. Having just bought some decent, middle-of-the-range headphones, I have been listening to a lot of Pink Floyd, a band who specialised in audio experimentation and sound-effects wizardry.

23 December

Based on a friend’s recommendation I took the plunge and made a start on watching The Fall a few days ago. It’s not quite a commitment on the scale of Spooks — three series, five or six 60-minute episodes per series. I have just finished series two (the final — and very much climactic —episode was actually 90 minutes: it’s intriguing where series three will go now).

Gillian Anderson, as the senior investigating officer DCS Stella Gibson, is outstanding as always, and the whole drama itself is excellently written. Two things stand out for me. The first is that the focus is as much on the killer as it is on Gibson and the police effort; the killer’s identity is revealed to the viewer from the beginning. This is very much not a whodunnit. Secondly, the drama doesn’t always go in the direction one might expect. Characters come and go; potential sub-plot developments, such as the shooting of DS Olson and his links to organised crime, or fallout from Gibson’s unorthodox sexual liaisons, are hinted at before melting away. Some might see it as flawed writing; I find its refusal to slavishly follow obvious narrative lines refreshing.

25 December

My intention is to use the last week of the year to work my way through a backlog of Guardian ‘long reads’, political articles, book reviews and the like that are increasingly cluttering up my coffee table. But I couldn’t resist making a start on Bring Up the Bodies, the second volume of Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy.

30 December

Two enjoyable films to finish off the year. The first was Lynn + Lucy, a story of a lifelong friendship that turns tragically bad. The eponymous women, both with young families, live in an undisclosed location that might be one of the new towns that orbit London. Though a very convincing depiction of working-class life, its themes and concerns cut across class boundaries, not least the toxic effects of rumour and gossip on friendships and communities.

The second was The Death of Stalin. I am not generally a fan of satirical films but the historical setting was irresistibly intriguing. The film is well worth watching for the way it lampoons the communist leaders of the day (Michael Palin as Molotov and Jeffery Tambor as Malenkov, in particular, were laugh-out-loud funny) and more generally in this populist age as a commentary on dictatorship and unfettered political power. Apparently the film is or at least was banned in Russia, an act of censorship by Putin’s regime that speaks volumes.