Books, TV and Films, November 2020

1 November

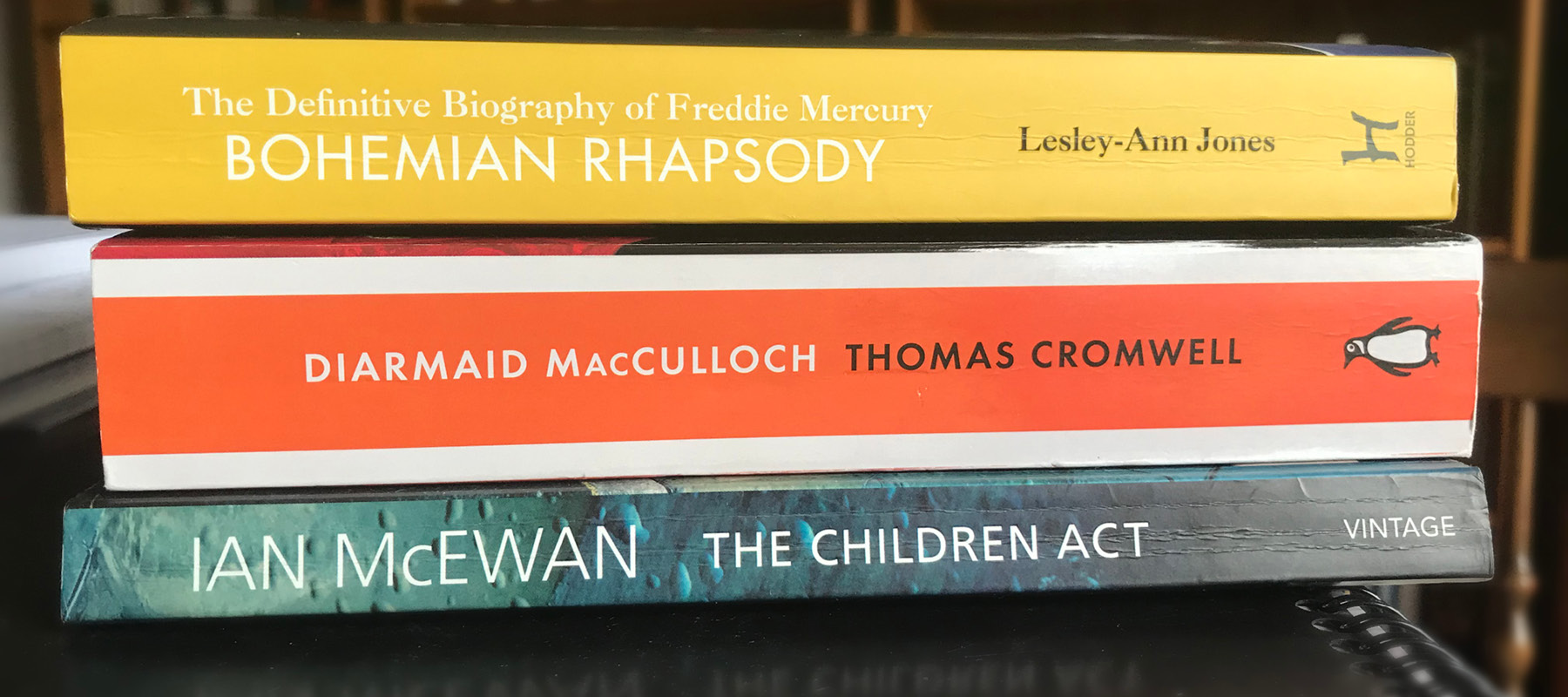

With a due sense of dread I have started to read Bohemian Rhapsody: The Definitive Biography of Freddie Mercury by Lesley-Ann Jones. I generally avoid the ‘popular’ biography genre — books about celebrities written for a mass-market audience. From the few I have read over the years (mainly about Queen), such books seem to be badly researched, full of drivel and appallingly written — like reading a 300-page edition of the Sun newspaper.

This particular book, which I picked up from a charity shop recently, was originally published in 2011 and then reissued in 2018 with a new title to cash in on the release of the Bohemian Rhapsody biopic. I am not aware of an official tie-in but snippets of the film script mirror the book’s contents (most obviously Freddie’s ‘coming out’ conversation with his girlfriend Mary Austin).

2 November

I have just watched a couple of terrific films — two snapshots, set a century or so apart, from America’s sad, shocking and shameful history of race relations. Despite adopting markedly different approaches to storytelling, both are tremendously uplifting.

Harriet is a biopic of Harriet Tubman, who first came to prominence in the 1850s (ie before the American Civil War) as part of the so-called underground railroad, having herself escaped slavery by walking over 100 miles from Maryland to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In total she is thought to have helped bring around 70 people to freedom. A remarkable woman, Tubman also played a prominent role during the civil war, before becoming involved in the movement for female suffrage.

On several occasions the film shows Tubman being ‘guided’ to safety after divine intervention in the form of messages received during fainting spells. (Tubman suffered brain injuries after having been beaten as a child by her slave master.) The film amply demonstrates how Tubman drew strength and succour from her religious faith, but this added mystical element detracted, in my view, from its impact as a historical account. The viewer is tempted to ask why such an apparently benevolent, omnipotent and interventionist God seemed happy enough to permit the barbaric practice of slavery to go ahead for hundreds of years.

The role of Tubman is played with fierce intensity by Cynthia Erivo. Her eyes seem to light up when she is confronted by one seemingly insurmountable hurdle after another. Sadly, the stories of women such as Tubman are not widely known. On a similar theme of women forgotten, ignored or airbrushed from history, Hidden Figures focuses on the stories of three black women who worked in different capacities for Nasa in the sixties, a time when the USA was demonstrably lagging behind the Soviet Union in the space race.

It is distressing to watch yet more evidence of the racial bigotry — ingrained and structural as well as everyday and casual — that was prevalent in large parts of the United States within the lifetime of many people alive today. And yet what is particularly enjoyable about Hidden Figures is that it drives its message home in a non-didactic and often humorous and irreverent way. To take just one example: an embattled head of the Space Task Group (played by Kevin Costner), frustrated by yet another setback, asks a room full of identikit white-skinned and white-shirted middle-aged men for reasons to explain the group’s lack of progress.

3 November

Another great film — A Beautiful Day in the Neighbourhood. Like, I suspect, many people in the UK, I had never even heard of Fred Rogers, a longtime children’s TV host in the USA. Fred is more than just everybody’s favourite uncle; he appears to be the epitome of goodness itself, like Nelson Mandela, Gandhi and Martin Luther King rolled into one. Lloyd Vogel is a troubled magazine reporter, with a track record of writing unflattering profiles of people. Given the task of writing a short piece on Rogers, a job he considers beneath him, his cynical mind is unable to accept that Fred can really be as saintly as he appears, and the reporter is determined to dig up dirt.

Others can comment knowledgeably about Tom Hanks’s portrayal of Fred Rogers. I was impressed that, though undoubtedly a feel-good film, it skilfully avoided the obvious risks of schmaltz and sickly sentimentality. The very final scene, Rogers alone at the piano as the production crew slowly leave the studio, perhaps offered an answer of sorts to Vogel’s doubts.

7 November

Where to start with the Freddie Mercury book? There has been enough teeth-gnashing to merit a separate blog. Meanwhile, we go from the ridiculous to (hopefully) the sublime — Diarmaid MacCulloch’s acclaimed biography, Thomas Cromwell.

14 November

When I woke up yesterday I listened to the news reports about continued upheaval in Number 10 following the resignation of Lee Cain as the government’s director of communications. By the end of the day Dominic Cummings, the prime minister’s top adviser, had also gone. Today’s Guardian headline describes it as the end of the “Cummings era”. How extraordinary it is that in twenty-first century Britain an unelected official should be seen as somehow defining an era. So often the machinations of government take place behind closed doors, and yet rarely do officials, advisers and civil servants have a public face.

And then I read this about Thomas Cromwell:

“By the second half of 1533, it was clear that the Secretaryship was in fact if not in name in Cromwell’s hands: one of those silent transfers of power to a man without a public face which characterised his first four years in royal service.”

Diarmaid MacCulloch, Thomas Cromwell

15 November

And so to the four-part BBC drama Roadkill. Written by well-known writer David Hare and starring Hugh Laurie, I knew it was going to be good — The Night Manager, also starring Hugh Laurie, was one of the best dramas I have seen for a long time — but it was so cleverly constructed I think it surpassed my expectations. I had rather assumed — based on I-don’t-quite-know-what — that the story would be about a devious, amoral, probably Tory politician, presumably a hit-and-run (‘Roadkill’), and consequent cover-ups and assorted dirty deeds and nastiness.

It was, of course, so much more. Yes, an investigative journalist is killed in a hit-and-run. And yes, a deer is run over in the middle of a country road. But the title ‘Roadkill’ needs interpreting much more broadly, perhaps taking in the sense of ‘collateral damage’. Like many of my favourite dramas, it combined plot and character development beautifully. It’s no exaggeration to say that not a single major character is completely flawless: all have their foibles and failings to a greater or lesser extent. It would be an interesting exercise to rank them in order of ‘goodness’. By the final episode I somehow found myself rooting for Peter Laurence (Hugh Laurie).

Roadkill was also a great advert for diversity: female prime minister; female chief of staff; female investigative reporter; female deputy editor at a big newspaper; female newspaper proprietor; BAME female top barrister; BAME barrister’s assistant; lesbian chauffeur; female permanent secretary in the Department of Justice etc. Hopefully there will come a time when we don’t even notice.

16 November

Fanny Lye Deliver’d is a low-budget production which demonstrates that excellent films don’t have to cost a fortune to make. Set in (Oliver) Cromwell’s England, it revolves around Fanny, her ageing husband John and young son. They live an austere life, according to a strict Puritan and highly patriarchal ethic: Fanny and her son are regularly beaten with a crop by John. Into their lives come a young couple with very different ideas about social and property relations.

The film clearly takes inspiration from the famous Marxist historian Christopher Hill. The words ‘The World Turned Upside Down’, which Hill used as the title of one of his books, are referenced in the film. It wasn’t clear exactly what ‘sect’ these new arrivals followed, but they were libertines, embracing sensual and sexual freedom as part of a general imperative to enjoy life on Earth (in other words, downplaying any notion of Heaven). As well as this battle of ideas, which brought to mind the late-sixties film Witchfinder General, the isolated cottage setting put me in mind of Straw Dogs, another film in which the established order is threatened from without.

18 November

Back to Ian McEwan. A few weeks ago it was On Chesil Beach. This time it is The Children Act. Both are films of McEwan novels, with screenplays written by McEwan himself. Both are excellent.

The Children Act centres on an eminent judge in the Family Division and a case involving a seventeen-year-old Jehovah’s Witness refusing — with the blessing of his parents and the elders of his church — a potentially life-saving treatment that involves the transfusion of blood. This was an interesting premise for me not least because I spent a year chatting weekly to two Jehovah’s Witnesses who patiently taught me about their beliefs.

25 November

I finally finished the Cromwell biography today. It is approximately 550 pages of fairly dense text, taking 20 days to work through at something under 30 pages a day on average. It was an enjoyable but not at times an easy read, certainly not for someone like me who is well read in neither church nor Tudor history.

A week or so after key prime ministerial advisers Dominic Cummings and Lee Cain left their posts, it was interesting to read about how quickly Thomas Cromwell, another power behind the throne, met his comeuppance. Even in the early months of 1540 there was no real hint of his coming fall, though his support for the marriage to Anne of Cleves was a disaster from the moment Henry VIII set eyes on her. Then, seemingly within days, Cromwell was gone, executed in July 1540. Henry’s obvious subsequent regret at his rash decision also reminds us in these last days of the Trump regime of the dangers of emotionally unstable and capricious leaders.

26 November

Having thoroughly enjoyed the film of The Children Act, I had to go back to the original novel. I have no knowledge of academic film studies, but it is interesting at least to note the differences between book and film — all changes made, presumably, for sound dramatic reasons. It is a guitar not a violin that Adam is learning to play in the film. The role of Pauling, Fiona’s clerk, is not so clearly defined in the book; in particular, he does not witness the kiss between Fiona and Adam as he does in the film. And the closing musical performance is realised quite differently in book and film.

In a mini essay at the end of the book the author makes clear that the legal cases he uses (or at least the main ones) are all based on real-life cases. The novel itself is yet another McEwan masterclass. Two passages, in particular, I found devastatingly good — his description of a legal case involving Siamese twins, and a jaundiced perspective on the reality of family breakdown and shattered communities.