Books, TV and Films, February 2022

7 February

I have always been an occasional reader of historical fiction, though it hasn’t been a conscious choice until quite recently. I just seemed to naturally gravitate towards books that were set in the past. Does Sebastian Faulks write historical fiction? I don’t really think of him that way, and yet novels like Birdsong and Human Traces are wonderful examples of the genre.

Reading Hilary Mantel and then Labyrinth by Kate Mosse (I think in that order) was a revelation: fiction as an introduction to historical periods and events about which I knew little or nothing. In this case, medieval France. Mosse made it all wonderfully accessible. I remember being barely twenty pages in when a voice shouted at me from off the page: This is fantastic. Why have you never taken an interest before, you idiot?

I have written more about historical fiction in my review of Hilary Mantel’s Bring Up the Bodies. And here’s my review of The Last Protector by Andrew Taylor.

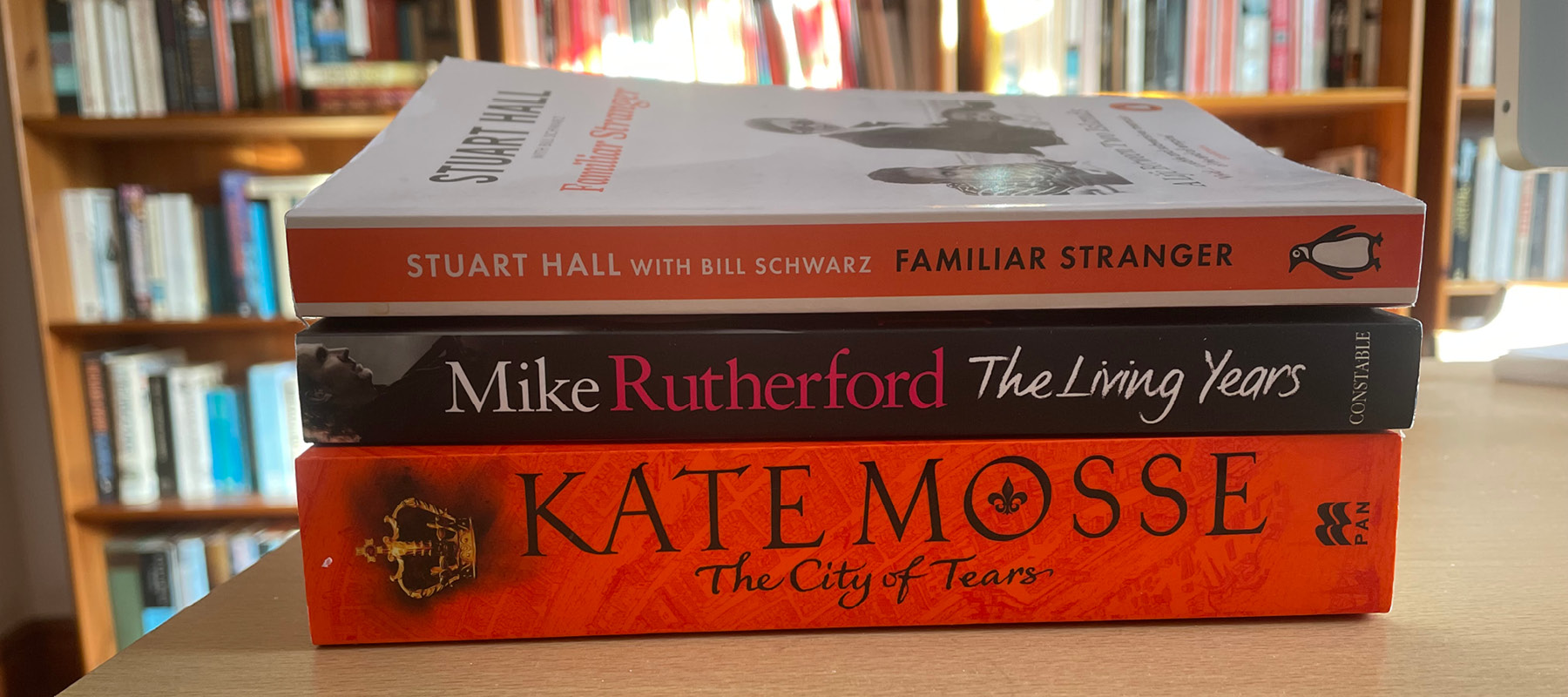

I read The Burning Chambers, the first in a new multi-book epic tale by Mosse, in 2019. The City of Tears is the follow-up. The city in question is Amsterdam, home to refugees from far and wide, though much of the story actually hinges on events in Paris in August 1572 — the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. The climax of the novel takes place on an island reliquary (a building that houses holy relics). Though complex religious and political divisions play a central role in proceedings, Mosse guides us expertly through them and at no point does the reader feel overwhelmed by complicated or unnecessary detail.

Mosse is also concerned with how we remember the past — not least the gaps and absences in the historical record. She is the founder director of the Women’s Prize for Fiction and the founder of the Woman in History campaign, so it is no surprise that the novel features a cast of strong female characters, none more so than Minou who, in addition to being wife and mother and châtelaine of the castle of Puivert, is also a chronicler:

Now writing was as necessary to her as breathing. A necessity, a responsibility. Her journals were no longer a history of her own hopes and fears, but rather the story of what it meant to be a refugee, a person displaced, a witness to the death of an old world and the birth of a new. Minou knew that it was only ever the lives of the kings and generals and popes which were recorded. Their prejudices, actions and ambitions were taken to be the only truth of history.

from Kate Mosse, The City of Tears

15 February

I like the first of the two Tom Cruise Jack Reacher films (the second not quite so much). However, fans of the books and — more importantly perhaps — Lee Child, who writes them, don’t. The actual Reacher character is (so people say — I don’t know) both a man-mountain and gruffly monosyllabic. Tom Cruise is neither. Child said that there’s wouldn’t be any more Cruise films and instead he has backed an Amazon reboot. It’s called Reacher, is made up of eight 50-ish-minute episodes and is based on the first novel (yes!), originally published in 1997. And it’s great. There are apparently some tweaks to bring it more up to date, but it certainly ticks the required man-mountain, gruffness and monosyllabism boxes.

19 February

Mike Rutherford’s The Living Years is the third (and best) Genesis memoir that I have read, the other two being Phil Collins’ Not Dead Yet and Steve Hackett’s A Genesis in My Bed. There’s also a heavyweight biography of Peter Gabriel that I haven’t got round to yet. Tony Banks has not (to my knowledge) published anything.

As I say, it’s the best of the bunch — certainly in quality terms. Rutherford is ex-public school, of course, so it’s reasonable to expect him to be able to string a few coherent sentences together. They’re all eminently readable and they all have good tales to tell but, compared to Hackett’s book in particular, Rutherford’s writing is much more organised and controlled. Where Steve assails the reader with exclamation marks and ellipses (…), Mike is considerably more reserved and understated, his line in humour deadpan and dry.

This is typical. It’s a description of Island Studios where the band were recording The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway.

There were two studios: a nice big one upstairs and a cheap, depressing one downstairs with chocolate-brown shagpile on the walls. We weren’t upstairs.

from Mike Rutherford, The Living Years

Ironically, at the foot of the page from which that quote comes (page 148) Mike uses an ellipsis — “but at that point I decided I needed some time out…” — but in this case I would say it’s warranted. It’s a nice way to lead into whatever the some-time-out stuff was.

The book’s title is of course a reference to the Mike + the Mechanics song about the death of a father. It’s a title well chosen. Mike’s at times difficult relationship with his father — a senior naval officer — is a thread that runs through the whole book. Extracts from his father’s unpublished memoirs (he died in 1986 but the memoirs were only discovered after Mike’s mother’s death in 1992 and were much later presented to Mike in bound form by his sons as a Christmas present, presumably the trigger for him to write these memoirs) crop up regularly, often judiciously chosen as counterpoints to Mike’s own career.

I liked the honesty in the book. At times, he can be quite cutting, not least about Genesis members past and present (though it may equally well just be his sense of humour). To take just two of many examples, we learn that Steve didn’t pay Mike and Phil for their contributions to Steve’s first solo album, and that Tony will never have a hit single because he “never did understand how to make words flow”. In fact, there are numerous barbs about Tony, presumably because they have known each other so long. “I think to this day Tony thinks his voice is better than it is” is one. Perhaps they are all in-jokes.

One thing that annoys me about celebrity biographies and memoirs is that the bulk of the material tends to be weighted towards the early years. Once the said performer(s) hit(s) the big time, the detail seems to thin out — as if it’s all in the public domain already or there isn’t really much of interest to tell. In Philip Norman’s Shout! The True Story of the Beatles we are told on page 178 of a 423-page book that Love Me Do (the first single) was released on 4 October 1962. We reach the first Smiths gig on page 149 of Johnny Rogan’s 303-page Morrissey & Marr: The Severed Alliance.

(Note also how stars seem far more willing to write about the early years of grinding poverty — “I’ve paid my dues” — than about the years of fabulous wealth. One minute it’s all battered vans to gigs and poky hotel rooms and the next we’re headlining Knebworth.)

Rutherford’s book is for the most part more balanced than many I have read, though he says surprisingly little about Foxtrot — a big breakthrough album for Genesis — and Wind and Wuthering, which, along with Selling England by the Pound (an album Mike doesn’t hold in as high a regard as I do) is probably my favourite Genesis album.

And then suddenly it all peters out. Thirty pages from the end of the book and we have reached the Invisible Touch album and tour in 1986–87. It’s the band at the peak of their worldwide popularity. It’s also when Mike’s father died, and so it’s the memoir’s natural end-point, given the way that Mike has crafted it. But real life doesn’t follow artificial story arcs.

We get a handful of pages about the 1992 We Can’t Dance period. A whopping two paragraphs about Phil’s decision to leave. Ditto the Calling All Stations period with Ray Winston. Less than a page…really? Talk about damning with faint praise. A little bit (but not much) more than this about the 2007 Turn It On Again reunion tour. And, well, that’s it. A hugely anti-climactic feel at the end (not unlike the Abacab album which finishes with the underwhelming and downbeat Another Record).

27 February

Mention the name AJP Taylor and there’s a good chance that someone will talk about his TV lectures, done to camera in real time and without notes. It’s said that he could time the end of the lecture to the second. They were groundbreaking in their day, though most of his TV work was before I became interested in history. He was ill and frail by the time he came to record his final TV lectures, How Wars End, in 1985, which I watched while at university.

The first intellectual I remember seeing/hearing on TV was, I think, Professor Stuart Hall of the Open University. He was a mesmerising, wonderfully articulate public speaker. I first became aware of Hall via the iconic magazine Marxism Today. He and Eric Hobsbawm were both big-name regular contributors. Hall it is, I think, who coined the term ‘Thatcherism’. He certainly did much to define it.

Stuart Hall never wrote a book alone. Collaboration was for him, it seems, a key part of the creative and intellectual process. And so it is with his posthumously published memoir, Familiar Stranger, written “with Bill Schwarz”. I had assumed that Schwarz merely completed it after Hall’s death but, true to form, it had in fact started life as a dialogue between the two men. Only late in the day, we are told, was it decided to frame the memoir in the first person.

Other than for his interventions in British politics in the Seventies and Eighties, my knowledge of Hall comes from my interest in the formation and early years of the so-called New Left in the late Fifties. Familiar Stranger covers the years up to the early Sixties. It is primarily about the part of Hall’s life with which I am least familiar: his childhood in Jamaica (he was born in 1932) and then his arrival in England as a Rhodes Scholar in 1951 and his time at Oxford.

It is a compelling memoir. Despite — indeed because of — his relatively comfortable upbringing, he had a troubled and unhappy childhood. In his words it is a story of disavowal, disaffection and “deep-seated disorientation” as his awareness and understanding of class, racial identity and what he calls slavery’s “afterlives” and the “trauma of the slave past” develop.

Ideas and concepts that I associate with Hall and with cultural studies — the academic discipline he did much to pioneer — underpin the whole book. That, I guess, is the point. Hall was interested in how we relate to and make sense of the world around us. It makes for a stimulating though not always easy read.