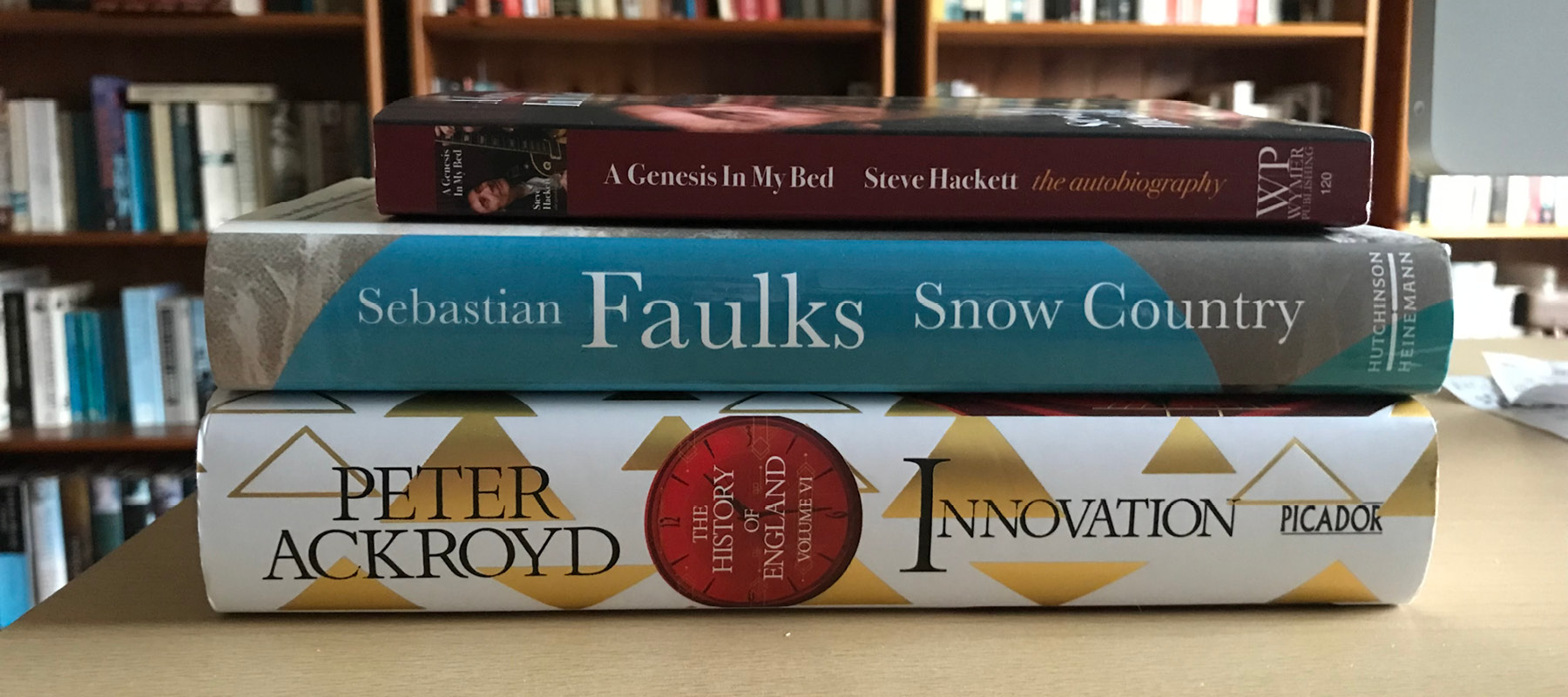

Books, TV and Films, November 2021

7 November

Steve Hackett played guitar in the ‘classic’ Genesis line-up of the Seventies, of course. These days I count myself as a huge fan of his solo work too. I bought his (excellent) third album, Spectral Mornings, way back when it was first released in 1979, having been enchanted by the song Every Day. But I have only really got to know his solo stuff in the last few years, taking a chance on a 2017 album, The Night Siren, after which I picked up a cheap collection of five of his mid-career releases. His recent output — in terms of both quantity and quality — is phenomenal. In fact, unlike most late-in-their-career artists, he is currently producing the best music of his life.

Hackett has always been adept at channelling the many and varied cultural experiences and insights arising from his worldwide travels into both his music and lyrics, ably assisted by his (now) wife Jo. However, though his albums are always lyrically interesting, he isn’t a natural wordsmith — which is partly what makes A Genesis in My Bed, his 2020 autobiography, an uncomfortable read, for this fan anyway.

And that’s a shame — because he has an interesting story to tell, one that frankly I was not expecting. Periods of drink, drugs, and darkness and depression — who would have thought it of the bloke sitting quietly and undemonstratively stage-right on those early Genesis tours, shielded behind the heavy-rimmed glasses, the thick, black beard and the dark clothes. Steve’s choice of book title — a reference to, well, that would be telling — is in itself revealing.

The writing isn’t dreadful. Here’s his description of the postwar London of his childhood, for example:

Crumbling pillars adorned sad facades, appearing ripe for slum clearance. Together those houses resembled rows of rotting teeth with the odd gaping black hole of a bombsite to completely ruin any semblance of a smile.

from Steve Hackett, A Genesis in My Bed

However, in all likelihood the book is more or less a DIY effort — and it shows. We can forgive the occasional typo, tautology and other minor errors; I have yet to read a book that is completely error-free — and what I write certainly isn’t. It’s other stuff that is infuriating. The book cries out for a professional’s guiding hand. I can’t imagine for a moment that Steve would allow his music to be released without an appropriate level of quality control.

Exclamation marks litter almost every page! Paragraph after paragraph ends with the dreaded three dots, like a bad case of measles…

And then there is the constant metaphor overload. Take this run of sentences, for example:

A whole world of possibilities was revealing itself, starting as a trickle and becoming a flood. Once I’d opened Pandora’s Box there was no stopping me. During the tour, the ideas continued to germinate.

from Steve Hackett, A Genesis in My Bed

A good editor would also have helped organise the material: at one point he briefly covers the A Trick of the Tail period (an important moment, as it was the first album and tour without Peter Gabriel), then moves on to Wind and Wuthering, and then returns to discussing the A Trick of the Tail tour again.

As a Genesis fan, I was certainly interested to read his account of his years in the band, his decision to leave and his ongoing relationship with the remaining band members, Tony Banks, Mike Rutherford and Phil Collins. He clearly felt extremely close to Peter, the first of the classic line-up to fly the nest. The most barbed comment is aimed in Mike’s direction — he claims that in the 2014 Together and Apart BBC documentary Mike had asked for more focus on his own solo career at the expense of Steve’s — and he also makes clear that, though open to taking part in the 2007 reunion tour, an invite was never on the cards.

Another problem with the book is what is left out, relating to the years 1987 to 2007. We are informed in an afterword — presumably published only in the paperback edition and not in the original hardback — that his career “felt like swimming uphill and it was an emotionally traumatic period for me as well”. Why, then, write an autobiography, one wonders? There was also much, we are told, that he was not allowed to write about for legal reasons…

15 November

A quick burst of film-watching during the football break, featuring two actors whose films I always look out for. The first was Cold Pursuit, which stars Liam Neeson as Nels Coxman. It’s fair to say that Cold Pursuit left me, errm… cold. The father-out-for-revenge plotline obviously brings to mind the excellent Taken, but this time the setting is a ski resort in Colorado and his unusual skillset is the ability to drive a snow plough. If that sounds flippant, it’s in keeping with the film itself, with its Tarantino-esque mix of ultra-violence and cartoon comedy. It also has two seriously underwritten female roles — first, a new-on-the-block police officer and, second, Coxman’s wife. (What was the marvellous Laura Dern thinking when she took the role?!)

The Little Things was much better. There’s Denzil Washington, as watchable as always, and also Rami Malek, suitably enigmatic, like any self-respecting Bond villain should be. The story of a hunt for a serial killer covers not unfamiliar ground — slick, smooth and smart young high-flier meets (metaphorically) battered and bruised old hand with a dark secret to hide. With its shadowy settings and grizzly murders, there a definite noir-ish feel to it all, not least in the pleasingly ambiguous ending.

18 November

Unlike Steve Hackett, Peter Ackroyd certainly is a wordsmith — and as prodigious a writer as Steve is a musician. I have collected Ackroyd’s multi-volume history of England since picking up a copy of the first volume, Foundations, in a remaindered-books shop. In my review of Steven Pinker’s Enlightenment Now I credited Ackroyd with helping ignite my interest in the distant past, his felicitous prose “a sure guide through the byways of early England”. The sixth and final volume, Innovation, covers the twentieth century.

It is a tall order for a writer like Ackroyd to tell the story of the twentieth century in 460 pages. He has real literary flair — and not just in the sense that he writes exceptionally well. He is astonishingly well-read and clearly has deep literary and cultural sensibilities. It’s no surprise that the best sections of the book cover social, cultural and artistic themes.

His pen portraits are often a delight, he has an ear attuned for gossip and scandal, and his frequently acute observations come wrapped in nicely judged aperçus. How about this for a summary of suburbia: “This was the English family’s hallowed plot of land, the city dressed up in country clothes.” Or this, on the Church of England: “It is hardly coincidental that the Church’s reputation for gentle compromise arose just as its political influence began to falter.”

I think it is Steven Pinker (yes, him again), in his book A Sense of Style, who recommends that if you must use a cliché, at least do something with it. Give it a twist. Don’t just regurgitate it. Step up, Peter Ackroyd: “If India was the jewel in the diadem of empire, East Africa was the string of pearls binding it.”

This style doesn’t work quite so well when it comes to political history. Ackroyd isn’t a professional historian — he is described on Wikipedia as a biographer, novelist and critic — though much of his work is history-related. There is the odd slip-up (for example, referring to the February and November revolutions in Russia — it’s generally written as either February/October or March/November) and the acknowledgement of research help at the front of the book isn’t a feature of the preceding volumes. There are no footnotes to balance Ackroyd’s tendency to make sweeping generalisations. “The endless slaughter prompted English soldiers to ask why they were fighting” is one such example.

Here’s another:

At long last, the threat of Fascism was widely recognised. “We’ll have to stop him next time,” people commented in pubs across the country.

from Peter Ackroyd, The History of England Volume VI: Innovation

The multiplicity of events and developments, and sheer wealth of information out there, makes for some unusual subject choices. The world war bit of the Second World War whizzes by — barely has Hitler declared war on the USA than we’re celebrating VE Day — and yet he devotes several precious pages to the Exchange Rate Mechanism debacle in the Nineties. And I was astonished that, for someone with such cultural awareness and who has written on gay history, he makes just one (passing) reference to Aids.

More generally, the final third of the book — from, say, the early Seventies — drifts along without any sense of a unifying theme. (I am struggling, by the way, to understand why he has called this sixth volume ‘Innovation’.) The chapters seem suddenly to lose coherence and sense of direction — beyond the obvious chronological one. The text reads increasingly like a running commentary on events, stories that might have been worthy of a banner headline at the time but now seem no more than ephemera. Perhaps his assistants have been overzealous in their researches. Or perhaps, after six volumes, even the workaholic Ackroyd is tired. Who wouldn’t be?

I can’t put the book aside without highlighting this snippet of Ackroyd mischief:

According to the National Review, Churchill’s act of treachery [crossing the floor of the House to join the Liberal Party] was typical of “a soldier of fortune who has never pretended to be animated by any motive beyond a desire for his own advancement”. The accusation of egotism would be repeated throughout Churchill’s career, along with the related charges of political grandstanding and of an addiction to power. Civil servants complained that Churchill was unpunctual, prey to sudden enthusiasms, and enthralled by extravagant ideas and fine phrases. He was a free and fiery spirit who inspired admiration and mistrust in equal measure. Allies hailed him as a genius, while his enemies regarded him as unbalanced and unscrupulous.

from Peter Ackroyd, The History of England Volume VI: Innovation

Yes, you read that right. It says ‘Churchill’, not ‘Boris Johnson’ (who has of course written a biography of Churchill. Click to read the excoriating review by Richard Evans).

20 November

“I’m fighting a powerful impulse to beat the hell out of you.” It is a fairly safe bet that if they ever remake the film Marnie, this particular line of dialogue — said by Mark Rutland (Sean Connery) to the eponymous kleptomaniac, Margaret ‘Marnie’ Edgar (Tippi Hedren) — won’t make it into the revised script. It is by no means the only uncomfortable element of Alfred Hitchcock’s mid-Sixties psychological thriller. But times change and films are as valuable and revealing a source of information about the attitudes and manners of the day as, say, a novel.

Watching Marnie we see that the people making the decisions are male, the ones writing those decisions down are female. While wives dutifully look after the home and flaunt their jewellery on social occasions, husbands smoke cigars, drink whisky and talk business. When Marnie’s horse writhes around in pain following an accident and urgently needs to be put down, the manipulative sister-in-law begs to be allowed to ‘get one of the men’ to do it. And when Marnie refuses to have sex with Rutland on their honeymoon (after a marriage that she has been blackmailed into agreeing to), he takes what is ‘rightfully’ his anyway, despite promising that he wouldn’t.

23 November

Secret Army, currently showing on the Drama cable channel, is another TV series I have fond memories of from childhood. First shown in 1977, it tells the story of a resistance movement in German-occupied Belgium during the Second World War. ‘Lifeline’ helps Allied airmen, shot down by the Germans, get back to Britain.

In terms of production and feel, it has much in common with — though I don’t hold it in quite the same esteem as — the legendary series Colditz. Indeed, familiar faces crop up in both — most obviously Bernard Hepton. There is much that I would not have picked up on as a young child — for example, the tension between the Luftwaffe major, Erwin Brandt, and the fanatical Nazi, Gestapo Sturmbannführer Ludwig Kessler, who is despatched to Brussels to bolster efforts to close down the evasion line. “I am not a member of the Gestapo,” protests Major Brandt at one point. It brings to mind series two of Colditz, which introduced Major Mohn as a new second-in-command, a fanatical (though non-SS) former member of Hitler’s personal staff.

I doubtless missed at least some of the bleakness too: Yvette’s refusal to help a Jewish family in the episode Radishes with Butter (because Lifeline was not equipped to run Jews); the probable murder of an on-the-run British airman by Albert (because he might give away the organisation’s secrets if captured) in Sergeant on the Run.

A great series. Only one thing lets it down: its success spawned the truly awful ‘Allo ‘Allo! sitcom.

29 November

And finally this month, more magic from the wonderful Sebastian Faulks. Whenever I am asked about my favourite novel, I say Human Traces. It’s as good an answer as any. In addition to everything else I love about Faulks’ writing, it also has huge intellectual ambition. Human Traces is a big book in every sense, charting the development of psychiatric medicine and psychoanalysis in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. If Ackroyd opened my mind to the distant past (see above), Sebastian Faulks did much the same for my interest in what might (very) loosely be termed science.

Human Traces tells the story of two pioneers in the field of psychiatry, one English and one French, who open a sanatorium — the Schloss Seeblick — in Austria. Snow Country is, in Faulks’ own words, a sequel of sorts. He has been in ‘loose trilogy’ territory before with his ‘French’ novels — Birdsong, The Girl at the Lion d’Or and Charlotte Grey. Snow Country returns us to the Schloss Seeblick, which acts as a focal point, bringing together the novel’s two main protagonists.

Faulks is a master at interweaving epoch-defining events into the lives of individuals. Here the backdrop is both the Great War itself and more specifically the damage it wrought. Though the novel spans 20 years, much of it is set in the Thirties, a time of huge uncertainty across Europe. The economic depression has eroded the hopes and optimism of the later-Twenties. Authoritarianism and fascism are everywhere on the rise; democracy, by contrast, is everywhere in retreat, not least in Austria itself where ‘Red Vienna’ is at loggerheads with the Catholic hinterland. It is in these unpropitious circumstances that Anton and Lena — and others — try to find a sense of meaning in their lives.