Books, TV and Films, March 2022

9 March

I first became aware of Gyles Brandreth via his appearances on Channel 4’s Countdown in the early-ish eighties. Muddled memory confession time: I always thought of him as the second occupant of Dictionary Corner, following a lengthy Kenneth Williams residency, until I was reminded – I think after reading Richard Whiteley’s autobiography, Himoff! – of Ted Moult, who did a week or so at the very beginning.

I was in the sixth form at the time and Gyles was as passionate about words as my brilliant and somewhat eccentric Latin teacher, Eddie Scholes. They were both besotted with dictionaries (Countdown used the Concise Oxford, the one we had at home) and particularly the etymology of words.

Words. If there is one word that comes close to encapsulating or at least connecting the vast range of Gyles’ passions and pursuits, that’s perhaps the one. Words on the page. Words spoken. Wordplay. The after-dinner circuit. The Oxford Union. Awards ceremonies. Dictionaries. Novels. Diaries. Plays. The theatre. Radio. Shakespeare. Oscar Wilde. Jane Austen. Quotations. Anecdotes. Scrabble. Winnie the Pooh. Grammar, punctuation and the use of English…

…Writing a musical. Setting up the National Scrabble Championships. Writing a biography of Frank Richards (Billy Bunter’s creator). Pitching to revive Billy Bunter on TV. A one-man show at the Edinburgh Fringe. A teddy bear museum…

The only word Gyles doesn’t seem to know is ‘stop’.

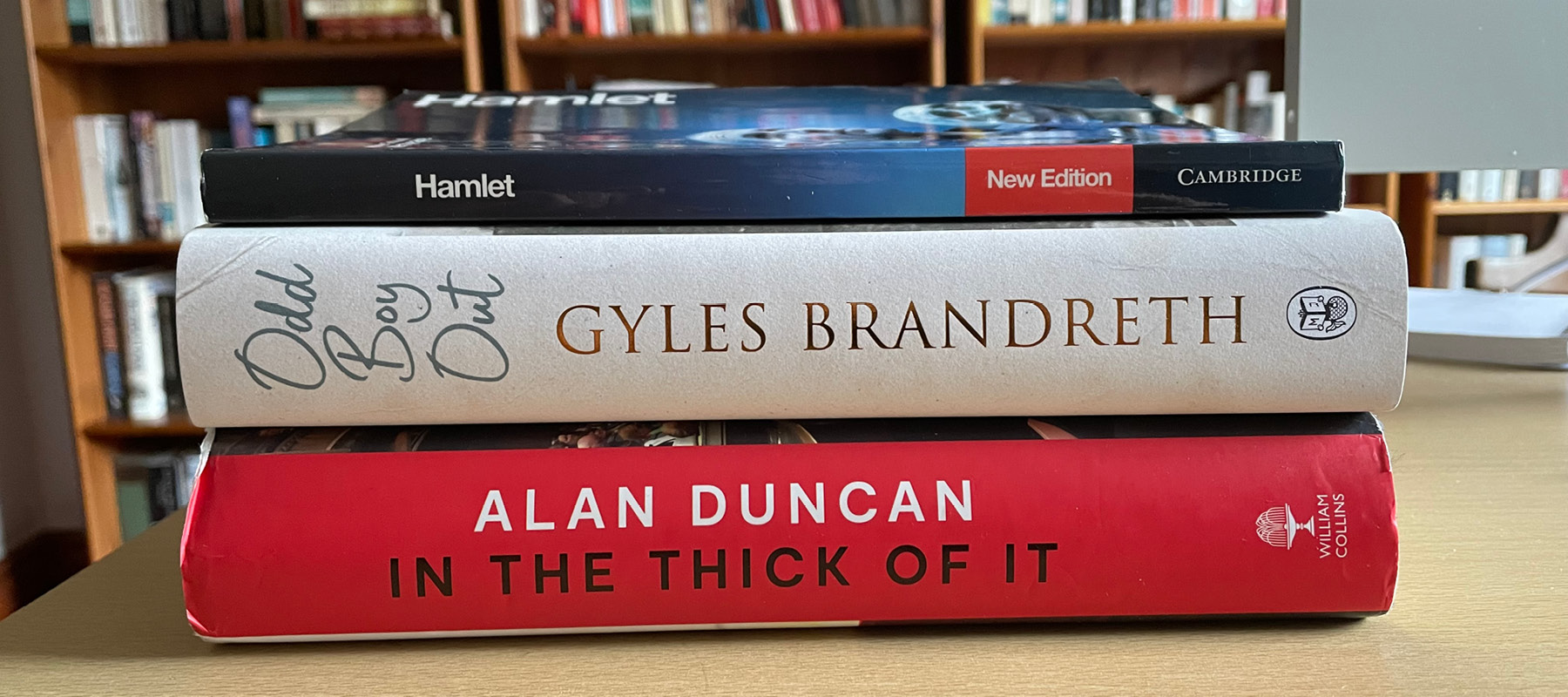

His recently published memoir, Odd Boy Out, was high up on the must-read list. I had thoroughly enjoyed both sets of Gyles’ published diaries. Something Sensational to Read in the Train runs from 1959, when he was at prep school, to the turn of the millennium. Breaking the Code, meanwhile, covers his years as an MP, including a period in the whips’ office, and is an excellent insider’s perspective on the 1992–97 Major government.

“Do forgive the occasional aside. I’ll try not to overdo it…” Yeah, right. Gyles is a wonderful raconteur and storyteller. He both speaks and writes beautifully – and he makes it all seem so effortless. And what’s more, none of it feels contrived. You can hear his voice on every page and believe that all these things really did happen to him, more or less as described. Odd Boy Out is often laugh-out-loud funny and wonderfully — shockingly — indiscreet.

In the prologue he unleashes a first-rate anecdote about the Queen, the Duke of Edinburgh and male strippers from the time he sat with them (TRHs – not the strippers) in the Royal Box at the Royal Variety Performance. Yes, really. On to some family history in chapter two (never my favourite bits of biographies and memoirs; I am hopeless with family trees) and suddenly the reader is knee-deep in a tale about Donald Sinden. And it doesn’t let up.

We are, he says, moulded by our parents. Are we surprised that Gyles loves anecdotes when his father “measured out his life” in anecdotes? Is it any wonder that he knew large chunks of Milton at the age of six when his father performed dramatic dialogues at his bedside while his mother read him nursery rhymes? Where Stuart Hall recoiled from the circumstances of his upbringing [see my review of Hall’s memoir, Familiar Stranger], Gyles embraced it all.

I always used to think of Gyles as quintessentially, comfortably, smugly middle class. It’s how he himself, in Odd Boy Out, characterises his upbringing. But it came at a cost — literally. There was never enough money. To quote Gyles, money worries wore his father down and then wore him away. Perhaps if the children hadn’t all gone off to boarding school (three to Cheltenham Ladies College and one to Bedales) or if the family hadn’t spent so much time in Harrods, things might have been different.

Gyles is a show-off, a showman and a shameless namedropper – the latter a reminder that he really has met just about everybody (there’s a nice recurring ‘I shook the hand that shook the hand…’ line). Although he doesn’t appear ever to have struggled to get mainstream media work – and is currently a regular on programmes like ITV’s This Morning and the BBC’s The One Show – I have no doubt that plenty of people dislike him intensely. The Times referred to him as “the Marmite of light entertainment”.

He can certainly do silly – he is something of an expert at standing on his head, a skill which he has demonstrated in some rather unlikely places. He’s a bit too full-on at times. And then there are the jumpers. It’s also a fairly safe bet that adjectives like smarmy, superior and too-clever-by-half have attached themselves to his name on a not infrequent basis over the years.

In Gyles’ defence it is something that he readily acknowledges. This is how Part 2 begins:

I realise now that I must have been a ghastly child. I was insufferable: precocious, pretentious, conceited, egotistical.

from Odd Boy Out by Gyles Brandreth

But one of the many joys of Odd Boy Out is that, as we turn the pages, we get to know the other Gyles, the one that doesn’t make an idiot of himself by wearing a silly jumper and standing on his head. So there is plenty of sadness, regret, guilt and self-criticism in these pages alongside the laughs, jokes and tall tales. And he’s the one tapping the keys on the final chapter, which takes the form of a letter to his late father and which movingly brings together the different strands of the story he has delighted us with over the preceding 400 pages.

Except, that’s not quite all. There’s a short epilogue, beginning with his wife Michèle knocking on the study door. How odd, because the prologue begins with his wife popping her head around the study door: “She never knocks. She likes to keep me on my toes.” Perhaps we can’t quite believe it all.

17 March

I was surprised by the number of swear words in Odd Boy Out, though any profanity is (almost?) invariably uttered by someone other than Gyles, usually as added spice in the many tasty anecdotes he serves up. Even the C-word makes an appearance or two – not something I imagine is heard very often on the This Morning sofa. It seems to be the insult of choice for the luvvie-darling set. Perhaps Shakespeare is at the root of this. See, for example, Act 3 Scene 2 of Hamlet in which the prince of Denmark, subjecting Ophelia to a fair amount of sexual innuendo, refers to “country matters”.

Why mention Hamlet? Because – after Odd Boy Out – where else but Shakespeare? If Gyles Brandreth can recite some of the great soliloquies à la Laurence Olivier before the age of ten, I can surely cope with a bit of Shakespeare.

I haven’t read much – Twelfth Night at school and Romeo and Juliet and Macbeth more recently. The obvious stumbling-blocks are the archaic language and the many references to customs and contextual events that the modern reader is unlikely to be familiar with. My expert guide through Hamlet was the excellent Cambridge School Shakespeare series.

Its layout is reassuringly user-friendly. The text of the play is set out on the right-hand page of each double-page spread, and the notes appear on the facing page. Sandwiched between a short summary of the action and a glossary of tricky words and phrases is the editors’ input – a mix of explanation, thoughtful commentary and ideas for students (and actors) to help them further explore the various characters, issues and themes.

There are familiar phrases on virtually every page, of course – only some of which I was aware of as being Shakespearean in origin. Take “Angels and ministers of grace defend us!”, from Act 1 Scene 4. It’s a ‘Bones’ line in Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, by far the best of the original Star Trek films.

28 March

I think it was Alastair Campbell who said that when a new volume of his diaries came out the first thing that everyone did was turn to the index to read what he had written about them. Something similar probably happened after word spread about In the Thick of It, the diaries of ex-Conservative MP and government minister Sir Alan Duncan, published last year.

Duncan is brutal at times. To give just a flavour, Fiona Hill (adviser to the PM) is “mental”, Emily Thornberry is “a graceless frump” and Priti Patel is “a nothing person”. It is curiously reassuring that Duncan’s opinion of the talents of Patel and fellow Conservative Gavin Williamson is as low as mine. And it is safe to say that Tobias Ellwood (at the time a ministerial colleague of Duncan) will not have found these diaries a comfortable read.

The cut and thrust of politics, perhaps, though I was troubled by the number of times Duncan makes reference to someone’s physical appearance when insulting them. An irksome local party member is described as “the most ugly nasty shit in the Association”, and he calls the prominent Tory Eric Pickles a “fat lump”.

Such unpleasantness aside, the diaries are a great read, helped by the fact that Duncan can write a decent phrase – “a barrage of Farage”, “a relentless wankfest”. His is a semi-insider’s perspective on a key moment in modern British history. The diaries cover the period from the start of 2016 (the Brexit referendum was in June of that year) to the end of 2019, when the Conservatives led by Boris Johnson won the general election. Duncan was a self-styled “lifelong Eurosceptic” who plumped for Remain and then watched helplessly (despite – indeed, because of – his position as a Foreign Office minister) as the government made a total shambles of the Brexit process.

Diaries usually reveal much about the diarist. Duncan clearly has a high regard for himself, often despairing of those around him – see the Ellwood references – and there is an unspoken assumption that he himself could and would have done things better.

In his introduction Duncan makes the usual points about the value of diaries:

Journalism is often called the first draft of history, but a diary is a primary source. Whereas our newspapers express the nation’s prejudices, a diary can provide an unfiltered account of events. Assuming it is written up at the time, unvarnished and in the moment, it can capture the hardest thing for any historian to reconstruct – the feeling of the time, with all its uncertainties and lack of hindsight.

from In the Thick of It by Sir Alan Duncan

Absolutely, though of course the editing process – the deliberate choices over what to include and what to exclude from the published version – is itself a form of filtering, meaning that even ‘unvarnished’ diaries give us a partial and sometimes misleading representation of events.

Here’s an example relating to Boris Johnson, about whom Sir Alan has much to say. When Duncan was appointed to the Foreign Office by Theresa May in July 2016, Johnson was the foreign secretary, and therefore Duncan’s boss, until he (Johnson) resigned almost exactly two years later. Although the two men got on reasonably well during their time together, Duncan had little regard for Johnson’s abilities as a serious politician. He says this of Johnson – and plenty more besides – in his entry of 24 September 2017:

I have lost any respect for him. He is a clown, a self-centred ego, an embarrassing buffoon, with an untidy mind and sub-zero diplomatic judgement. He is an international stain on our reputation. He is a lonely, selfish, ill-disciplined, shambolic, shameless clot.

from In the Thick of It by Sir Alan Duncan

Following Johnson’s resignation in 2018, Duncan sees him as “a much reduced figure”, with little support in the parliamentary party. On Saturday 8 September Duncan tweeted that “this is the political end” for Johnson. Thereafter there are few mentions of him, other than for what Duncan calls his wrecking tactics, until we are well into 2019. Theresa May stepped down as prime minister in June and Johnson comfortably won the subsequent leadership election.

My point is not that Duncan was wrong in his 2018 judgement about Johnson’s future prospects but that – presumably as a result of the editing process – the diaries do not accurately reflect how support for Johnson subsequently grew to such an extent that, on 8 April, Duncan was warning his preferred candidate, Jeremy Hunt, “that if he doesn’t rev up his leadership efforts now he’ll never catch up.”