Books, TV and Films, April 2022

4 April

When plans for the film Ammonite, about the nineteenth-century English fossil collector and palaeontologist Mary Anning, were announced, I assumed – wrongly, as it turns out – that it would concentrate on her struggles to be recognised for her expertise and pioneering work. In fact, other than brief scenes in the British Museum that top and tail the film – a new exhibit that makes no mention of Mary’s role in finding and identifying it – the emphasis is very much on her life in Lyme Regis and a love affair with Charlotte Murchison who, though wealthy and privileged, is trapped in a stifling, loveless marriage.

It’s hard to go wrong with a cast that includes Kate Winslett, the ever-wonderful Saoirse Ronan and Fiona Shaw. Perhaps there could have been more of a focus on Anning’s palaeontological work. On the other hand, Ammonite convincingly depicts the squalid living conditions endured by the vast majority of people in the nineteenth century and their desperate lives of struggle, toil and heartbreak, with many (women especially) starved of emotional and intellectual as well as physical nourishment. Mary’s mother – with whom she lives – is obsessed with cleaning eight animal figurines: we learn that they represent her dead children.

I dug a bit deeper into Mary’s life story after watching the film. It seems that – unlike the portrayal of her in Ammonite – it is not certain that she was a lesbian. I have written here some thoughts about ‘fake’ history and film.

Ammonite was one of two films about pioneering nineteenth-century women that I watched this month – the other being Miss Marx. The eponymous Miss Marx is Eleanor Marx, daughter of Karl Marx and herself a revolutionary socialist. Much of the film is set in the drawing rooms of relatively wealthy socialist campaigners and left-wing intellectuals; their middle-class comforts and bohemian lifestyles are a world apart from the lives led by the likes of Mary Anning. Miss Marx is the story of Eleanor continuing the work of her father, in particular by active involvement in workers’ struggles and in promoting women’s rights. Her commitment to her father’s ideas is shown via (short) straight-to-camera political monologues – not the only strikingly unusual directorial touch.

The film delivers two emotional punches. The first – more of a relentless pummelling of the ribs than an upper cut to the chin – is Eleanor’s long-term relationship with fellow socialist Edward Aveling, who is both hopelessly profligate with money, wasting the legacy left to her by family friend Friedrich Engels, and emotionally and sexually unfaithful to Eleanor (to the extent that he secretly married another woman using a pen name). The second is the discovery – shown here as a death-bed admission by Engels – that her father was the unacknowledged father of Freddy, the child of the Marx family’s long-time housekeeper Helene.

It’s all very mainstream and conventional. But, of course, Eleanor Marx was not at all mainstream and conventional by the standards of the time, and so director Susanna Nicchiarelli makes a valiant attempt to capture and convey Eleanor’s free spirit. The opening credits are the first clue – all flashing images and raucous music, not perhaps the first things we associate with Eleanor Marx. It is the final moments of the film, though, that offer up a real taste of Eleanor’s bohemian sensibilities: a drugged-up freak-out – or is it a meltdown? – to the accompaniment (again) of a punk rock soundtrack.

12 April

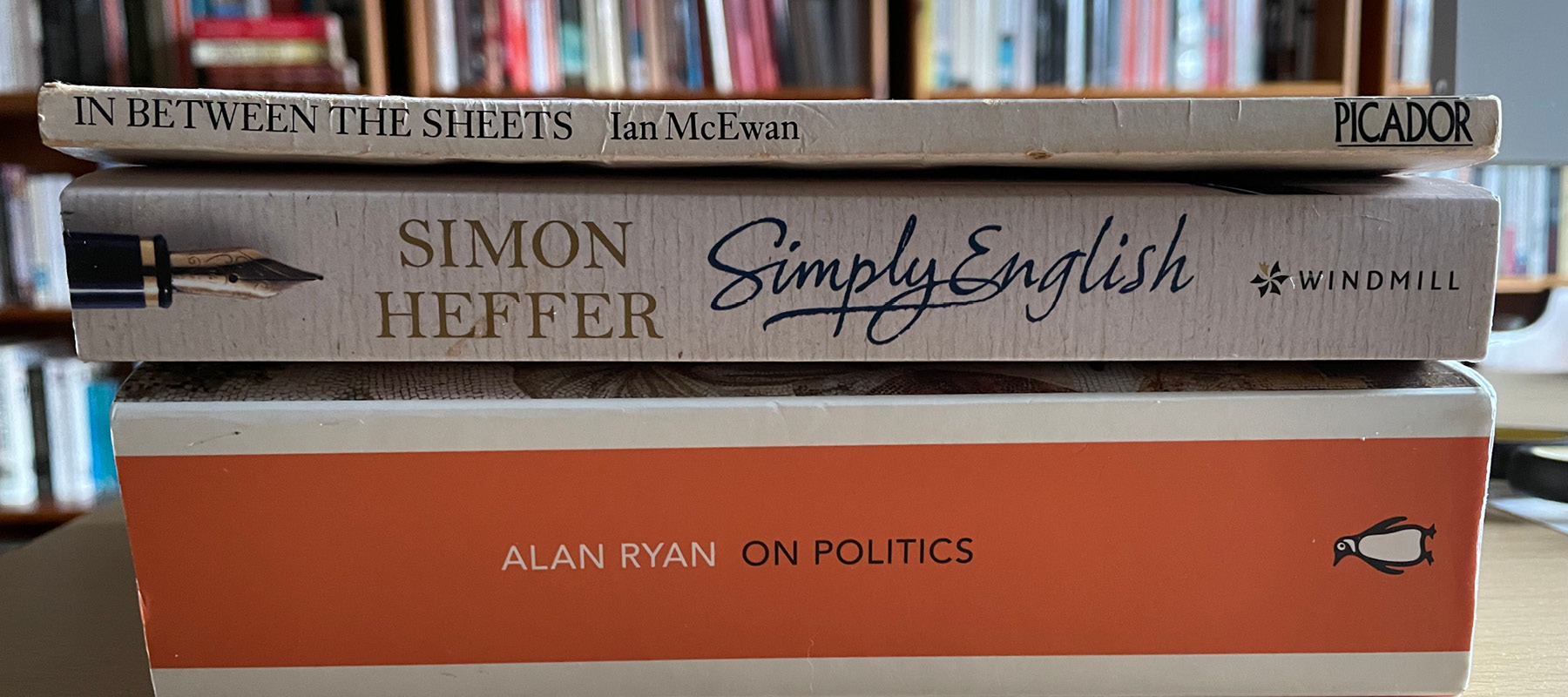

I have been slowly working my way through Simon Heffer’s Simply English: An A to Z of Avoidable Errors. As I wrote in the introduction to my free-to-download style guide, there is no one definitive set of rules governing the use of English. There are, of course, many ‘rules’ that are more or less universally accepted. But there is also a large and expanding grey area about which there is much less agreement.

Hence the large number of style guides and books – and websites these days – about the use of English. Each reflects the approach to writing English and even something of the personality of the particular writer or organisation. I enjoyed Steven Pinker’s The Sense of Style and, even more so, Gyles Brandreth’s Have You Eaten Grandma – the latter probably the best book for anyone who wants a funny and accessible introduction to writing well, or at least accurately.

I really shouldn’t like Simon Heffer – but I do. He is a historian and a political commentator, very much on the right politically. Something of a big beast in the Tory world, he has had long spells at the Daily Mail, the Daily Telegraph and the Spectator. His books include a very good (but inordinately long and detailed) biography of Enoch Powell. Much the same could be said about his book High Minds, which I read recently. His first book on grammar and the use of English – called Strictly English – came about after emails sent by Heffer to colleagues at the Telegraph pointing out errors in their writing appeared on the internet. Yes, you get the picture.

There is actually much to admire in Heffer’s advice. He has no time for writing that he considers overinflated, pretentious or affected, and he emphasises the importance of writing clearly and plainly. He hates clichés, the use of which displays “a paucity of original thought”. On the other hand, it’s not hard to guess what his view is of what he calls ‘political correctness’ and I quickly lost track of the number of times he uses words like ‘ignorant’ or ‘barbaric’ in his A–Z. Language does evolve; that’s a simple fact. And so it was interesting to note the (many) examples of things Heffer says are just plain wrong that are nevertheless listed in Lexico, Oxford’s online dictionary, as legitimate (or at least widely accepted) uses of English.

This is typical of Heffer’s approach – part of the entry for Clergy, writing to or addressing:

The Reverend John Smith or the Reverend Mary Smith is correct. The Reverend Smith is not. His or her Christian name [Christian name, note, not forename, given name or first name], or rank, is required …The Reverend Smith is the product of that most God-fearing of countries, America, but is an abomination here.

from Simply English: An A to Z of Avoidable Error by Simon Heffer

I looked up ‘abomination’ to check the literal meaning: it is ‘a thing that causes disgust or loathing’. Again, you get the picture.

19 April

I have thoroughly enjoyed watching Old Henry – a tough and gritty western. Like The Homesman – which I discussed here – and a 2017 film starring Christian Bale and Rosamund Pike called Hostiles, it offers what we might call a ‘revisionist’ or ‘realist’ representation of the American West. Old Henry depicts a bleak, unforgiving and frequently unpleasant world. This is the reality of rugged individualism. The West is a violent place, with the law often far away. Guns are a part of everyday life but – and this is what I particularly like about these revisionist films – most of the people who fire them aren’t good shots. They’re not marksmen. Most of their bullets miss their target. When they do hit someone, it hurts and causes a bloody mess. As I said about The Homesman, these films aren’t like the sanitised westerns on which my generation grew up.

Contrast that with 2 Guns. Any film described as ‘buddy cop action comedy’ should carry a health warning: ‘Do yourself a favour and watch Lethal Weapon instead’. Predictable, stale, unoriginal: the only thing bigger than the body count was the cliché count. Even Denzil Washington couldn’t make it enjoyable to watch.

The bad guys are bad. The good guys are stand-up comedians. And everybody is a tough guy. There are firefights aplenty, naturally. And, of course, the bad guys never hit their target and the good guys never miss theirs. In fact, bullets don’t really hurt – the good guys even shoot themselves for laughs and presumably because bad-guy bullets bounce off them.

It’s possible that there is a slow-motion shot of a good guy walking nonchalantly away from an exploding building. It’s also possible that I fell asleep and dreamt that particular scene.

23 April

Going back a couple of years or so, I really enjoyed the 2017 film The Man with the Iron Heart, about the assassination of the fanatical and ruthless Nazi Reinhard Heydrich during the Second World War. He was killed in Prague in 1942 when he was governor of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. In retaliation, the Germans razed the village of Lidice. Operation Daybreak is an earlier film of the same events – it was made in 1975 – and features a very young-looking Martin Shaw as one of the assassins (though he was actually 30 at the time). Anton Diffring plays Heydrich: as a blond-haired, blue-eyed actor, Diffring was a staple of Second World War films of the 60s and 70s – The Colditz Story and Where Eagles Dare, to name but two.

Once again – see my comments on Ammonite above – there is a question mark with Operation Daybreak concerning its historical accuracy: for example, the film gives the clear impression that this was a British-planned operation whereas in fact the British Special Operations Executive played more of a supportive role. I keep asking myself: does it matter and does it make the film any less good?

28 April

‘Magisterial’. A seriously overused word, a favourite of non-fiction book reviewers and frequently used in puff-quotes that publishers splash across book covers to entice the reader. And here it is again, used to describe On Politics: A History of Political Thought from Herodotus to the Present by Alan Ryan. ‘Magisterial’ comes from the Latin ‘magister’, meaning teacher or schoolmaster, and means ‘having or showing great authority’. It’s right up there with ‘authoritative’ and ‘definitive’ in my if-I-ever-see-this-word-again-it-will-be-too-soon list.

That’s not to say that On Politics isn’t written with great authority. Alan Ryan is a Fellow of the British Academy who has spent a lifetime working at the world’s top universities. Still, even a thousand-page book can only scratch the surface of such a vast topic as the history of political thought so, other than ‘we can trust Ryan’s analysis and judgements because he knows what he’s talking about’, I’m not really sure what ‘magisterial’ really means here.

In recommending the OUP ‘A very short introduction to…’ book series, Ryan describes the chapters of his own book as ‘very very short introductions’. Other than the final hundred or so pages, On Politics is made up of chapters that focus on the big hitters who have contributed to the development of political thought in the West – from the ancient world to the end of the nineteenth century. The final few chapters, by contrast, are thematic, focusing on topics such as imperialism and nationalism, socialism and democracy.

Most chapters are arranged in the same way – usually starting with a ‘life and times’ section, for example. In a book of this length it’s no real surprise that sentences like this crop up now and again: “…a string of articles in the 1930s criticised Dewey from the standpoint of a more Augustinian standpoint.” There are also phrases and even more or less whole sentences that turn up more than once within a few pages of each other.

More disconcerting – especially for a book with the word ‘magisterial’ on its cover – are the factual howlers, which are particularly noticeable in the sections relating to Russian history. There is a reference to the end of serfdom in 1862, for example; it was 1861. Ryan also writes about a Russian translation of Das Kapital in 1867 and the despotic near-theocracy over which Alexander III then ruled: Das Kapital was published in 1867 but the first Russian edition only appeared in 1872 and Alexander III didn’t become tsar until 1881. Later there is a comment that Lenin was wounded by a would-be assassin in 1922, two years before his death. In fact, the assassination attempt, by Fanny Kaplan, was in 1918; it was a stroke that severely debilitated Lenin in 1922.

It’s easy to pick holes. Everyone makes mistakes. In the grand scheme of things these are minor errors. It’s a massive book and mistakes are bound to slip through. All true. It’s just that I always find myself thinking: if these are errors that I have spotted because I know a bit about the topic, what errors are there in the sections I am not familiar with?

Anyway, putting these minor mistakes to one side, On Politics is a book I enjoyed reading from cover to cover – I spent most of the month on it – and one that I have no doubt I will be dipping into regularly in future. I found the chapters relating to the Middle Ages particularly illuminating.

30 April

Just time to read In Between the Sheets, a (short) collection of short stories by Ian McEwan. I love The Cement Garden, his first novel, published at roughly the same time. McEwan’s early stuff reminds me of the David Lynch film Blue Velvet, the opening shot of which establishes an everyday scene in smalltown America before zooming in on a bloody, rotting amputated ear lying in the grass. McEwan seems to focus in on the out-of-place, the bizarre, the outlandish, the extraordinary amidst the ordinary – people, scenes and situations that once upon a time might have been described as ‘freakish’.

Two Fragments, for example, is set in a post-apocalyptic London. In the first ‘fragment’ a father and his young daughter watch as a girl stabs herself through the stomach with a sword, her father passing round a collecting tin to the watching crowd, claiming that she will perform the feat without drawing blood. In Dead as They Come, a man falls in love with a mannequin, buys it from the shop and takes it home to live with it. Oddly enough, their relationship doesn’t last.

As I say, this is early McEwan – and he certainly seems to be experimenting with form. As a dabbler in fiction reading, I found some of them more accessible than others (which is another way of saying that I probably missed a great deal). To and Fro, to use another example, seems to be about a man lying in bed in the middle of the night, thinking about (a) where he is at that moment, his lover beside him, and then (b) an earlier office scene. The paragraphs alternate – to and fro – between the two situations.