Queen I Review

“Queen I is the debut album we always dreamed of bringing to you.” Brian May and Roger Taylor, 2024

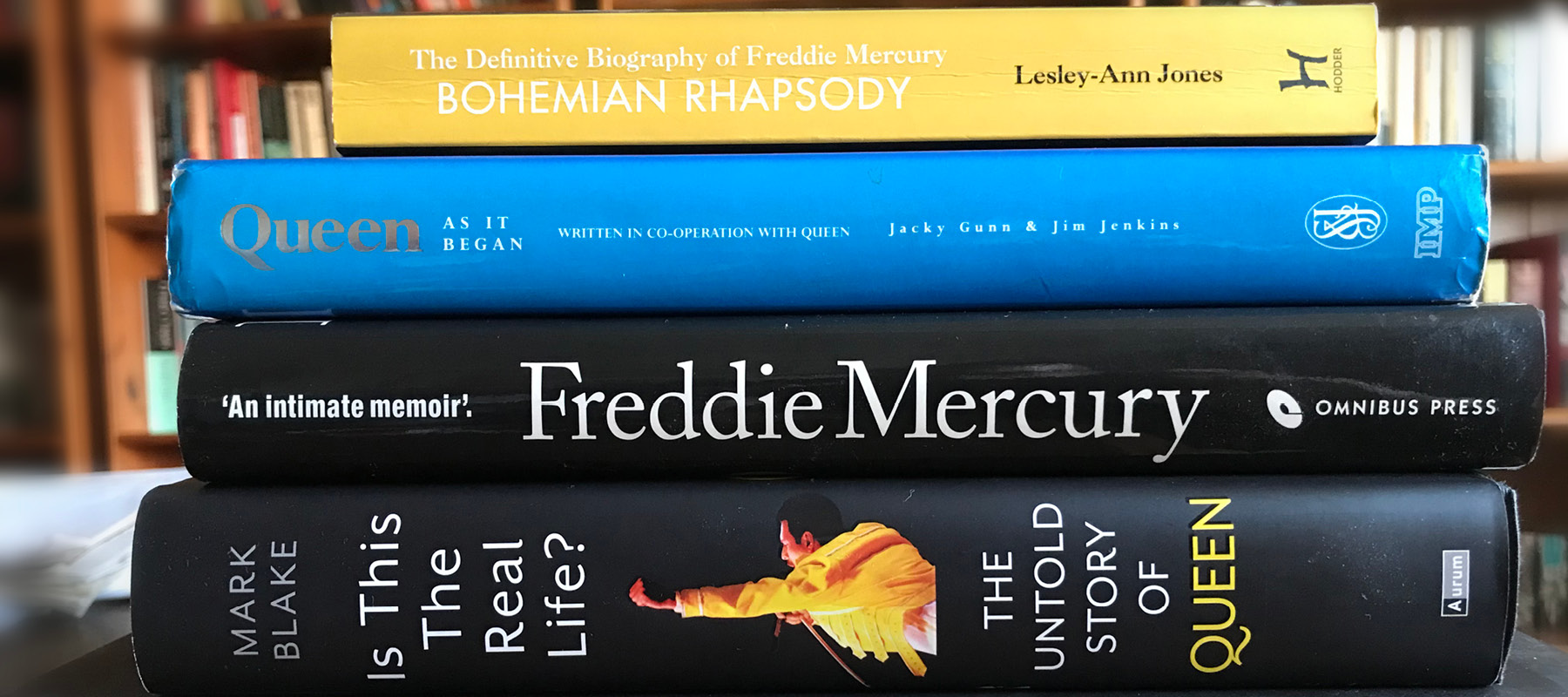

The Queen I box set, which was released in October 2024, is the third Queen studio album to get the Collector’s Edition treatment following on from the News of the World fortieth-anniversary release in 2017 and the Miracle box set in 2022.

It appeared fifty-one years – why not fifty? – after the debut album first came out (on 13 July 1973, to be precise). What sets this Collector’s Edition apart from the other two is that it is a full remix – the word “rebuild” appears in the publicity blurb – of the original album, hence the decision by Brian and Roger to re-title it ‘Queen I’ (as opposed to the original title, ‘Queen’).

The box set includes plenty of other goodies for fans to enjoy as well, but I rather suspect (and everything I have seen on various YouTube channels in the last few months seems to confirm this) that the new mix will be the main topic of conversation among Queen aficionados.

Here is what Roger has said:

Essentially with the Queen I box set we’ve made the actual album sound the way we wanted it to sound, using the techniques that we have now. We’ve made the drums sound like they should sound, and the overall sound of it is better, the mixes are better. So it’s been a delight to improve it, to bring it up to where we wanted it to be.

So – is the remix/rebuild any good?

We had an early clue with the release of the track The Night Comes Down as a single (if that is what they are still called). I thought it was absolutely terrific, but one talking head after another quickly popped up on YouTube to voice their unhappiness and to complain in particular about the use of pitch-correction on Freddie’s vocals. Well I am certainly not a music production or singing expert (I think I sing like an angel but everyone else says I am completely out of tune) but I can’t make out any difference in the vocals. If pitch-correction has been used it certainly doesn’t spoil my listening experience.

What I can hear clearly now – and this is typical of the experience of listening to the album as a whole – are Freddie’s ‘oh-oh’ and ‘mmm’ ad-libs, over the top of the three harmonised voices, at 3:04 and 3:19 respectively. Going back to the original version again, they are indeed there but just not distinct enough for me to have been conscious of them before. Perhaps it is the new mix or perhaps it is Dolby Atmos helping us hear things that were buried in the original mix – or more likely a combination of the two.

Anyway, the new mix reanimates the track and enables the listener to experience a familiar song in a new and exhilarating way. Brian’s acoustic guitar is so intense as it crescendoes, and – listening more closely to Roger’s drumming – I had never previously registered just how unconventional his fills are (reminding me, oddly enough, of Ringo’s drumming on Ticket to Ride).

As I say, the same applies to the album in its entirety: the whole thing – but particularly the drums and the guitars –sounds fresh and fabulous. There is an energy, a vibrancy and a heaviness to the songs that is somehow absent on the original release. Yes, there has been knob-twiddling going on in the production room, but it is tin-eared to claim that it doesn’t sound great. As Phil Aston commented on his Now Spinning magazine YouTube channel, sceptical Queen fans should give the new mix a proper listen – and with an open mind – before condemning it.

As for the argument that it is sacrilege to mess with the original recordings, I don’t have an issue with using new technology to overcome previous production limitations or to correct decisions taken at the time about how the album should sound. (It is worth reading what Geddy Lee writes in his autobiography My Effin’ Life about his and Alex Lifeson’s reaction on first hearing a playback of their debut album – “crestfallen”.)

From the opening notes of Keep Yourself Alive – you can imagine Brian’s sixpence attacking those strings – Queen I is a joy to listen to. Every track has its standout moments – those earth-shattering electric-guitar breaks on Doing All Right; Roger’s drumming on Great King Rat, Liar and Modern Times Rock ‘n’ Roll; the final section of Son and Daughter (from roughly 2:20 onwards) that sounds so much more like the version they were playing on stage.

But two stars in this firmament – two songs that I have long thought are often overlooked and underappreciated – shine brightest for me.

The first is Jesus – one of Queen’s earliest songs and an early home for some extended guitar wizardry from Brian. Jesus is a good example of the ludicrous way Queen allocated songwriting credits before 1989. Brian has previously said (I think talking about the song Liar) that Freddie insisted that whoever wrote the lyrics ‘owned’ the song. And yes, it is highly likely that Freddie wrote the lyrics of Jesus (the religious theme was typical of his lyric-writing at this time) and perhaps even the basic song structure, but I would need some convincing that it wasn’t Brian who developed and arranged the entire guitar passage.

And the second is My Fairy King, which just sounds so achingly plaintive and beautiful – “Someone, someone – has drained the colour from my wings / Broken my fairy circle ring…” Some of the seeds of Bohemian Rhapsody may be found in The March of the Black Queen on Queen II but, with the frequent changes of pace and the air of melancholy, they are there in My Fairy King as well.

And for the first time ever I can more or less make out what Freddie is singing. Even when the lyrics were officially printed for the first time (as part of the 1994 Remasters series), some of the lines didn’t make much sense to me. These lines are from the 2024 printed lyrics:

They turn the milk into sour

Like the blue of the blood of my veins

(Why can’t you see it?)

Fire burn in hell with the cry of screaming pain

(Son of heaven set me free and let me go)

Sea turn dry no salt from sand

Seasons fly no helping hand

Teeth don’t shine like pearls for poor men’s eyes – no more

The vinyl version of the Miracle re-release (but not, frustratingly, the CD) made a big thing of restoring the dropped song Too Much Love Will Kill You back to its ‘rightful’ place on side one, and the Queen I release does the same with Mad the Swine, apparently left off the original release after a disagreement between the band and producer Roy Thomas Baker.

Mad the Swine had already seen the light of day as one of the additional tracks on the twelve-inch release of the single Headlong in 1991. Musically, it is lighter and more upbeat than the rest of the album, though its story of a saviour (Jesus, presumably) is – as noted above – very much in line with Freddie’s lyrical preoccupations at the time. I commented in my Queen Song Ranking that I was intrigued where in the album’s running order the track would have gone. Well, now I know: between Great King Rat and My Fairy King on side one.

CD2 is the – cliché klaxon – ‘legendary’ De Lane Lea demos (ie the first ever tracks they recorded in a professional recording studio, between December 1971 and January 1972). I was a bit surprised that these demos are on CD2 because, apart from the length of the CD (it is only five tracks and less than thirty minutes long) they are already available on the 2011 deluxe edition of the first album.

However, the tracks that appeared in 2011 were taken from a scratchy acetate in Brian’s private collection. The versions included here have been restored and remixed from the original multi-tracks. They sound great.

The band themselves always preferred the De Lane Lea versions – “…we have always felt that the performances actually have more spontaneity and sparkle, as well as the benefit of more natural sounds” (to quote some of the info in the box set) – to what appeared on the debut album in 1973. The curious fan can now make their own mind up by comparing and contrasting the 1973 version of, say, Keep Yourself Alive with the De Lane Lea demo and the 2024 mix.

CD3 (which I would have expected to be CD2) is called Queen I Sessions, even though some of what we hear is from the De Lane Lea sessions as well as from Trident Recording Studios where the Queen album was recorded.

The Sessions CDs were highlights of both the News of the World and the Miracle releases and the Queen I Sessions CD doesn’t disappoint either. Listening to it is a fascinating fly-on-the-wall experience; we are ear witnesses to a band more or less at the very beginning of their recording career, learning how to record songs in a professional environment.

Note, for example, the band’s efforts to keep in time (Freddie does a lot of counting) and the not infrequent slip-ups. Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised, given that much of the recording of the first album was apparently done during ‘down time’ in the middle of the night. The camaraderie between the four of them shines through too. My favourite (said by Brian): “It’s you, Bulsara! It’s you that’s flat, you bastard!”

CD4 consists of backing tracks – rarely a mix I reach for by choice – and CD5 is Queen at the BBC, eleven performances of songs recorded (or part-recorded – they sometimes just added vocals and guitar to backing tracks due to time constraints) during four BBC sessions between February 1973 and April 1974. These have all been previously released, but it is nevertheless a fantastic addition to the box set if you don’t own Queen On Air.

CD6 are live tracks. Five of them, recorded at the London Rainbow on 1 March 1974 on the Queen II tour, are already available, but then we get four gems that should be of real interest to any Queen fan.

Two of them were recorded (presumably from the soundboard) in San Diego on 12 March 1976, the final date of the North American leg of the A Night at the Opera tour. Neither has appeared on any official Queen live album. One of them is Doing All Right and the other is Hangman, a song that was often played live in 1973 and occasionally thereafter but was never recorded in the studio.

The other two tracks are from the band’s very first gig in London, on 23 August 1970, at Imperial College (ie pre-John Deacon’s arrival). One is a version of Jesus (which they had stopped playing live by 1973, Brian’s solo being incorporated instead in an extended Son and Daughter) and the other is a cover of the Bo Diddley song I’m a Man, which was also played as an encore on some nights during their 1977 European tour.

The sleeve notes state that the tracks were included for their historic significance and “do not represent the usual fidelity of professional live recordings”. Well yes, but all four tracks are well worth a listen.

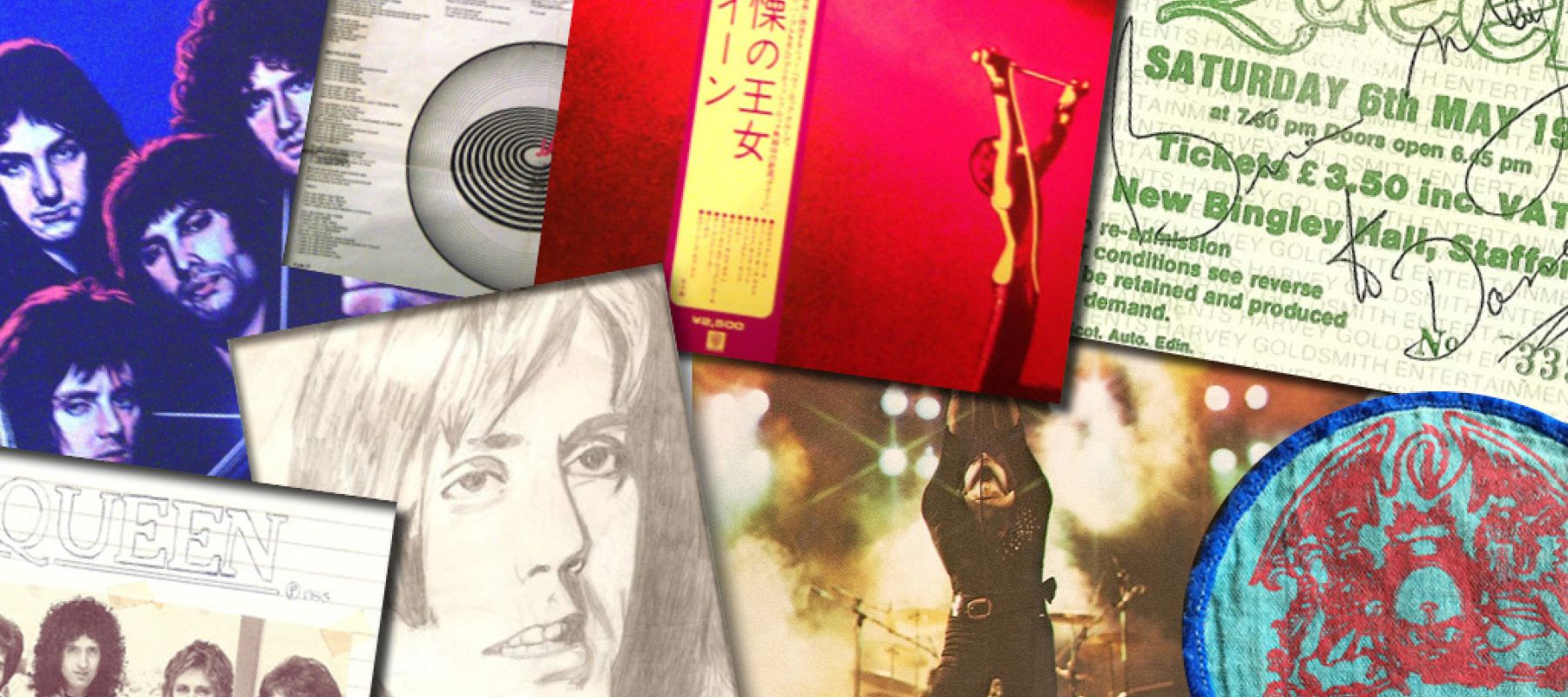

As well as the six CDs and a vinyl copy of the Queen I album, there is also a 108-page book. I was critical of the book that accompanied the Miracle box set, but this one doesn’t disappoint (as long as you don’t mind that some of the 108 pages consist of a single line from a song or a quote from a band member). It is packed with images of memorabilia such as handwritten lyrics and there are plenty of rare photographs of the band at work and play, many of them taken by a friend of theirs, Douglas Puddifoot, who supplied many of the photos that were used on the back cover of the original album.

Not part of the box set but of note are six short promotional videos released on the official Queen YouTube channel. They are worth a watch, particularly Episode 5 in which Brian explains how he had originally created the front cover from a Puddifoot photo (which is in the book) and then recreated it so it could be digitised for the Queen I re-release.

He also explains the reference in the original credits to ‘Deacon John’ – not, it seems, John’s idea. The credits are missing from the 2024 version of the album cover and the inner sleeve credits refer to ‘John Deacon’.

So, what’s missing? I would have liked to have heard more from the 1970 Imperial College gig and the full version of the 1973 London Golders Green concert originally broadcast on BBC Radio 1. A medley of rock ‘n’ classics was omitted when it appeared on the Queen On Air release in 2016, though perhaps there were copyright issues.

Completists will probably also rue the omission of the edited version of Liar released as a single in the USA by Elektra Records in February 1974 to coincide with their US tour supporting Mott the Hoople. There is also a 1975 re-recording of Keep Yourself Alive that featured on the 2011 deluxe edition of the A Night at the Opera album.

To conclude, then, this is my favourite of the three Queen box-set releases. It certainly isn’t cheap but for those on a budget there are less expensive alternatives. Queen I is available as a standalone CD, and there is also a two-CD deluxe edition featuring the new mix and the Sessions CD. The De Lane Lea sessions were also issued on vinyl for Record Store Day 2025 (though not being a vinyl buyer any more I have no idea how long this product will be available for).

Brian has indicated that he would like to do something similar with Queen II. Who knows whether that will actually happen but if it ever does it will be a must-have. Queen II is so densely layered that it would undoubtedly benefit from Dolby Atmos and a general refresh. That said, as I have written in my blog about Live Killers [link below], there is a gigantic pizza oven-shaped hole in their catalogue of rereleases still waiting to be filled.

More of my writings about Queen

Genesis Bootleg History Overview

This overview brings together links to all the blogs I have written in my Genesis Bootleg History series over the last five years. (Just jump to the bottom of the page if you want to bypass this little bit of what and why.) The series title itself is a bit ambiguous, I realised. For clarity, it is not a history of Genesis bootlegs. Rather, it is a stab at telling the story of Genesis – not just onstage but in the studio as well – through widely available bootlegs of some of the band’s live performances…

Seconds Out – The Greatest Live Album? What idiot gave such a ridiculous title to a blog about Genesis’s 1977 live double album? Errr…I did.

And why is it ridiculous?

Well, first, there is the adage that the answer to any headline (or in this case, blog) with a question mark in the title is almost always ‘no’.

And second – and far more important – who am I to pontificate about the greatness or otherwise of this or that live album? Who gives a shit what I think?

Yes, I am entitled to my opinion but, like everybody else, all I can possibly do is make judgements based on the live albums that I am familiar with. And to be honest, the list isn’t all that long. And that’s before we even start to unpick the whole knotty problem of what criteria we should use to assess ‘greatness’ when it comes to live albums.

(In my defence, I was overly influenced at the time I wrote that blog by SEO – search engine optimisation – which is basically about ways to get as many people as possible to click on your website. ‘Clickbait’ is another word for it.)

But writing the Seconds Out appreciation did lead directly to this Genesis Bootleg History blog series. I had been building up my bootleg collection over the years and so I was aware that – for all its brilliance – Seconds Out was presenting us with a rather misleading picture of the 1977 Wind and Wuthering tour.

And I am not referring to the tinkering – the fixes and overdubs and such like – that goes on in the studio afterwards. There were two even more basic issues with Seconds Out, I thought (and still do).

First, the music that was left out. Seconds Out omits all except one (Afterglow) of the songs they played from the Wind and Wuthering album. It also includes The Cinema Show, which was played (and recorded) on the A Trick of the Tail tour but then dropped.

Second, the chat that was cut out. It did not include any of the between-song nonsense that was such an integral part of the Genesis live experience. For example, side three of the original vinyl album opens with the words “supper’s ready” to introduce, well, Supper’s Ready. But what we miss out on is the whole story of Romeo and Juliet getting frisky at the drive-in. And if you hadn’t heard some bootlegs from the 1976–77 tours you wouldn’t have a clue who Harry is…

It is worth making the point, by the way, that the Three Sides Live album is arguably even more misleading about the Abacab tour.

So writing the Seconds Out blog – which is partly an appreciation of the album itself and partly an analysis of the album in the context of the Wind and Wuthering tour as a whole – sparked the idea of sketching out the history of Genesis via some of their bootlegs.

Bootlegs. A quick word about them.

They are essential listening for devotees of a band, offering a rawer, less polished and therefore more authentic picture of a live performance. Whether it is an audience recording, a soundboard recording or a live radio broadcast, we get to hear the rough edges, the mistakes, the miscues – in short, the stuff that gets smoothed over in (or chopped out of) any official release.

One moment captures the magic of bootlegs for me. It is from the Dijon 1978 show. Phil’s slightly off-kilter wail near the end of Afterglow, surely never to see the official light of day, is somehow perfect.

Some bootlegs are of course more listenable than others. All bootleg rating systems will have a ‘For collectors only’ category. As it happens, I get the impression that Genesis fans are luckier than most in terms of the number of high-quality bootlegs available.

That said, when I started this series I didn’t have a complete show from the Nursery Cryme era and I had never really bothered with the Foxtrot tour because of the existence of Genesis Live. (NB It is quite easy to find a version of Supper’s Ready from Leicester De Montfort Hall in February 1973 that was apparently included on test pressings of Genesis Live but left off the official release. Needless to say, it is great.)

And so my starting-point was Montreal in 1974 on the Selling England by the Pound tour. This bootleg stands out for two reasons in particular: Peter Gabriel’s French and the inclusion of The Battle of Epping Forest, which wasn’t one of the live tracks from the October 1973 London Rainbow show featured on the Genesis Archive 1967–75 box set (though you can find it easily enough online).

The Montreal 1974 blog established a template that I ended up using for the entire blog series: begin with some musical/band context, move on to discussing the then-current album and finish with an analysis of the live show, as documented by the bootleg.

(I have rewritten the original Seconds Out blog, focusing on the Dallas show of 19 March 1977, to fit this template. Dallas 1977: Genesis Bootlegs appears in the correct place chronologically. See below.)

I neglected the Lamb tour as well, partly because the entire set – with the exception of the encores – was made up of the Lamb album, and partly because the Genesis Archive 1967–75 box set includes a more or less complete show from the Los Angeles Shrine Auditorium in January 1975. I wasn’t aware until later how much polishing had been done in the studio before its release, particularly by Peter and Steve, so it is a tour that I will revisit at some point.

Anyway, I jumped directly from 1974 to the A Trick of the Tail tour in 1976, the first with Phil on lead vocals. It will be obvious if you read the blogs that I am much more a fan of 70s Genesis than anything that comes later, and I think the four tours between 1976 and 1980 are exceptional.

The Duke blog opens with the words: “Genesis, 1980 — and this time it’s personal.” Duke was the first album released when I was actually a fan of the band. As I go on to say in the blog, the lead-off single Turn It On Again and indeed the album as a whole felt at the time like a hugely unwelcome change of direction.

It was on the …And Then There Were Three… tour that Phil started to use the ‘new songs, old songs’ line that he continued with – with varying degrees of weariness and resignation – right through to the final tour in 1992. The medley was first introduced, in embryonic form, on the Duke tour. For better or worse, it became their way of acknowledging and accommodating the two very different eras of Genesis.

Something that I scratch my head about in the 1992 blog is whether we actually need bootlegs of the later tours. It is horses for courses, I guess. Bootlegs will always have value for hardcore fans – see my earlier comments about miscues and out-of-tune wails.

But – to repeat another point – if you are drawn to bootlegs mainly to hear what was omitted from official releases, it is at least debatable whether bootlegs are telling us much that we can’t glean from the CDs, DVDs and Blu-rays that followed on from those later-era tours.

Bear in mind that the final track (it.) from the aforementioned Lamb recording from the LA Shrine Auditorium in 1975 was missed, as were the encores, because the tape ran out. That wouldn’t have happened in 1992 or even in 1987. (The Wembley shows were apparently the first concerts ever recorded in HD. The ensuing video release lasts 132 minutes and features the entire concert, with the exception of the main In the Cage medley.)

[The plot thickens! Not more than two hours after I uploaded this blog, I read that a fiftieth anniversary box set of the Lamb album is coming out in 2025. It includes the previously released Los Angeles Shrine Auditorium recording – plus, so the publicity blurb claims, the missing final track and both encores. Well well well! Let’s see what we actually get!]

I ended the series with the We Can’t Dance tour of 1992, after which Phil left the band. After years of all but ignoring the 1997 Calling All Stations album (with Ray Wilson on vocals), I gave it a few plays not too long ago and actually quite liked it. (See my blog Calling All Stations: Not the Worst Genesis Album). But when I watched a video of the 1998 show at Katowice in Poland, it seemed so radically different from a traditional Genesis concert that I decided not to include it in this series.

I also decided against including the two reunion tours. I did think that one or two set list choices for the 2007 Turn It On Again tour were noteworthy, specifically the inclusion of Ripples and the exclusion of Abacab. Both decisions, in my view, to be applauded.

Using Carpet Crawlers as the second and final encore was also unexpected. I would have included it in the main set instead of Hold on My Heart and chosen another bona fide classic to end with. The Knife, maybe! Now that would have been fun!

On the other hand, it was disappointing (if not entirely unexpected) to see them lean so heavily on the Invisible Touch album in the latter part of the set – Throwing It All Away, Domino, Tonight, Tonight, Tonight and Invisible Touch. To be fair, they resurrected Los Endos, but see the blog about the 1992 tour for my thoughts on the song I Can’t Dance, which was the first encore. Here’s a clue: ugh.

And I thought long and hard about whether to get a ticket to see the Last Domino? tour – with Phil in a chair, his son on drums and two other non-Genesis musicians on stage as well as Mike, Tony and Daryl. I decided against.

I should say that (as will also be obvious if you read the blogs) I don’t have a musical background and claim no insider knowledge of the band. Nor have I listened to a particularly large number of Genesis bootlegs. I am just a longtime Genesis fan.

The bits of history I include in the blogs come from the obvious places. Armando Gallo’s book I Know What I Like gave me an excellent grounding in Genesis history when I first started listening to them at the end of the 70s. I have read the autobiographies written by Mike and Phil in the last few years, so some of the later blogs include quotes from those books. I only read Steve’s autobiography after I had written the blogs for the earlier tours. Most of the facts and figures (chart positions, touring revenues etc) come from Wikipedia.

My go-to website for tour dates and general bootleg information has been: https://www.genesis-movement.org. The homepage hasn’t been updated for a long time so I don’t know if it is still an active website, but the live database is excellent.

One last thought. There are several shows where Phil announces that they are recording (Hammersmith Odeon 1976 and Dallas 1977, to name but two). I am baffled why they have not yet put these out officially, or at least released a complete and unexpurgated version of Seconds Out, using the recordings from Paris, like Led Zeppelin did with the Madison Square Garden tapes from 1973 when they re-released The Song Remains the Same.

And finally, it would be impossible to highlight favourite songs or even favourite moments – there are far, far too many – but here are a few highlights (and lowlights)…

Tour:

1977; 1976 a close second

Bootleg:

Hammersmith 1976; Dallas or Zurich 1977; London 1980

Better tour than I expected:

1978 – the first without Steve

Best opening song:

Watcher of the Skies; Deep in the Motherlode; Behind the Lines

Biggest song choice surprise:

White Mountain brought back for the 1976 tour

Fountain of Salmacis brought back for the 1978 tour

Supper’s Ready brought back for the 1982 tour

Unexpected delight:

The Duke suite (particularly Duke’s Travels/Duke’s End) from the Duke tour

Worst moment:

Who Dunnit? from the Abacab and Mama tours

Biggest let-down:

I Can’t Dance closing the main set in 1992

Conversation Between Two Stools

Studio album:

Selling England by the Pound; Wind and Wuthering

Official live album:

Seconds Out; honourable mention for Genesis Live

Worst official live album:

The Way We Walk – The Shorts

The Way We Walk – The Longs

London 1992: Genesis Bootlegs

Like the story that we wish was never ending

We know some time we must reach the final page

Still we carry on just pretending

That there’ll always be one more day to gofrom the song Fading Lights

The hugely successful Invisible Touch world tour ended in July 1987 with four shows at Wembley – a then stadium record, for a short time at least – but there was a gap of almost four years before Tony Banks, Phil Collins and Mike Rutherford came back together, in their studio in Surrey, to write and record again as Genesis.

In the intervening years there had been no indication that Phil’s solo career was slowing down or that his global popularity was on the wane. His fourth solo album, …But Seriously, and singles such as Groovy Kind of Love and Another Day in Paradise, sold in prodigious quantities. A Seriously, Live! world tour and Serious Hits…Live! album (roughly four million sales in the USA alone) maintained his astonishing run of success. He sums up his ongoing solo success in his autobiography as follows: “…on both sides of the Atlantic, I bestride the changing of the decades like a Versace-clad, five-foot-eight colossus.”

Mike’s side-project, Mike + the Mechanics, was also enjoying mainstream success, most notably with the song The Living Years, which became a massive worldwide hit. (Mike used The Living Years as the title of his 2014 memoir, in which his relationship with his father features prominently.)

Of the three, it was only Tony who continued to find solo success elusive, despite releasing two interesting (and eminently listenable) albums in this period – Bankstatement in 1989 and Still in 1991, the latter featuring contributions from Nik Kershaw and Fish (ex-Marillion) among others.

We Can’t Dance was recorded between March and September 1991. As was now routine, nothing was written in advance; songs emerged spontaneously out of group improvisations. (The sessions were filmed and released as a 46-minute documentary called No Admittance.)

It’s a given – for this fan at least – that every Genesis album from Trespass to Duke is better that any album from Abacab onwards. But, of those later albums, We Can’t Dance is probably, possibly, maybe my favourite of the four. Today, at least.

Although several tracks from the album were released as singles, We Can’t Dance feels – on balance – less commercial than either the eponymous 1983 album or Invisible Touch, less like the band are trying to craft catchy, chart-friendly songs. This may be because lead-off single No Son of Mine – its subject matter domestic abuse and family rejection – is less obvious hit material than Abacab (the song), Mama or Invisible Touch (the song).

We Can’t Dance has a warmer, more natural ambience than its predecessors (particularly Invisible Touch), perhaps linked to a change of producer. Nick Davis, who had worked separately with both Tony and Mike, replaced Hugh Padgham behind the desk, the man probably most responsible for creating the slick Phil (solo) and Genesis sound of the 80s that was so commercially all-conquering.

The album certainly opens strongly with No Son of Mine, followed by Jesus He Knows Me and then Driving the Last Spike, and the ten-minute Fading Lights bring things to a close in fine style. Tony cited the latter song in a recent interview on the Classic Album Review YouTube channel as one of his favourites from the later years.

Dreaming While You Sleep has a powerful chorus and Since I Lost You gains emotional heft when you learn that the lyrics relate to the death of Eric Clapton’s young son. (Clapton was Phil’s neighbour and a close friend.)

That said, the rest of the album – songs such as Never a Time, Tell Me Why and Way of the World – sounds decidedly middle of the road, like the product of a solo Phil/Mike + the Mechanics mash-up. Worst of all is the execrable I Can’t Dance, which deserves to sit alongside Who Dunnit? from the Abacab album at the very bottom of any self-respecting Genesis song ranking. It is an excruciatingly risible attempt to be quirky and tongue-in-cheek (ditto the silly-walk video). Harold the Barrel it most certainly is not.

We Can’t Dance is a long album, the band taking advantage of the possibilities afforded by the (then relatively new) compact-disc format. At roughly 71 minutes, it is only ten minutes shorter than Led Zeppelin’s mighty Physical Graffiti double album. Many highly regarded albums from earlier decades offer less than 40 minutes of music. Rubber Soul and Revolver by the Beatles, for example, are only about 30 minutes long.

Would a slimmed-down We Can’t Dance, with the songs that comprise the mediocre middle third released instead as b-sides and bonus tracks, have been a more satisfying album, perhaps even worthy of comparison with some of the band’s 70s output?

Okay, maybe not. But it’s a thought.

Anyway, We Can’t Dance was released in November 1991 and became another massive worldwide hit, if not quite on a par with the success of Invisible Touch – but who is counting the odd million copies here and there? Tours of North America and Europe followed in 1992, ending with a concert at Knebworth on 2 August. After a seven-week break, there were further British dates in October and November.

And so we come to the choice of gig as the stop-off point for this blog: Earls Court, London – not, strictly speaking, a bootleg.

The starting point for this entire Genesis Bootleg History series was a blog I wrote about Seconds Out. It is a magnificent album, but it is also – and this is the point – seriously misleading as a document of the 1977 live show, omitting as it does all bar one of the songs they played from the Wind and Wuthering album. And not to mention all of the between-song banter, particularly from Phil, which was such an integral part of the Genesis live experience.

By 1992, things were rather different. Advances in digital technology meant that an entire two-hour-plus show could now be recorded and released, with few if any cuts and omissions. Add in a highly polished touring machine, able to traverse continents and deliver huge shows several times a week, and it is debatable whether a bootleg from the 1992 tour will tell us much that we can’t glean from official sources.

True, the two The Way We Walk live CDs – The Shorts and The Longs – are a hideous package (seriously, what were they thinking?), but we also have an accompanying live video (released in 1993 and then reissued with extra features on DVD in 2001) of the entire show. Professionally shot footage of the entire Knebworth concert (it went out on television in Europe) is also easy to find on YouTube.

As a side note, the music on the official CDs is taken from shows in Germany (as well as three songs from the Invisible Touch tour) whereas it is their three shows at London’s Earls Court that were filmed for the video release.

Anyway, the set list from Earls Court on 8 November was as follows:

Land of Confusion / No Son of Mine / Driving the Last Spike / Old Medley / Fading Lights / Jesus He Knows Me / Dreaming While You Sleep / Home by the Sea / Second Home by the Sea / Hold on My Heart / Domino / Drum Duet / I Can’t Dance / Tonight, Tonight, Tonight / Invisible Touch / Turn It On Again

I wrote in a previous blog that the choice of Land of Confusion as the set opener for the 1992 tour is a head-scratcher, but it is obvious from the video footage that the song is going down a storm. It is easy to clap along with and the singalong ‘Whao-oh’ lines in the chorus help establish an immediate rapport between band and audience.

“Make the pain / Make it go away”, Phil belts out in Mama. It is a mammoth Genesis song of the later era, but it survives only a handful of shows before it is dropped from the set, one assumes to protect Phil’s voice. An early show in Tampa, Florida was cancelled after just two songs after Phil developed throat problems. (Side note number two: the Wikipedia entry for the The Way We Walk video indicates that several of the songs on the tour were played in a lower key to adjust to a deepening of Phil’s voice.)

Abacab – another signature 80s song – has also disappeared. Nor will it be played on either of the reunion tours.

What is striking about the set list is the number of long songs: Driving the Last Spike, the Old Medley, Fading Lights, Home by the Sea/Second Home by the Sea and Domino. That is half the set. Factor in the (relatively) stripped-back staging and lighting on this tour and we are left with a sense of a definite gear-change compared to the 1986–87 tour.

Even frontman Phil – in fact, especially frontman Phil – comes across as somewhat restrained, subdued almost. There is less of the showman schtick, less of the clowning around. Gone are the Versace suits; jeans and a plain T-shirt will do just fine for this tour.

They have all now turned forty years of age and are doubtless aware that the last pages are being written of another chapter – perhaps the final chapter – of the Genesis story. Nothing conveys this sense of an ending as strongly as the elegiac Fading Lights, which includes the line “And you know that these are the days of our lives – remember”.

(These Are the Days of Our Lives is, of course, the title of a Queen song from their album Innuendo. It is one of several things the albums We Can’t Dance and Innuendo have in common. Both were released in 1991. They are, arguably, each band’s last ‘proper’ album. And some at least of the two bands’ longstanding fans regard these albums as a return to form after a run of patchy releases in the 80s.)

Jesus He Knows Me ups the tempo after Fading Lights. It is preceded by an extended Phil monologue about televangelists, which (a) presumably went down better in some parts of North America than others, and (b) all sounds rather odd when delivered to a British audience – but he repeats it anyway.

“So we’ve taken a few parts of our past and put them together and we’ve called it Some of Our Past Put Together,” says Phil at the Dodger Stadium, Los Angeles on 18 June. His introduction ahead of the Old Medley reminds me of his “lamb stew” quip on the A Trick of the Tail tour.

The Old Medley itself – now roughly twenty minutes long – consists of Dance on a Volcano, The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, The Musical Box, Firth of Fifth and I Know What I Like, plus snippets of a few other songs. It all flows nicely enough, but it remains what it always was – a somewhat unsatisfactory compromise that the band have been falling back on for a decade and more.

It is an attempt to accommodate two very different eras of Genesis, enabling them to play “lots of new songs and, with a slight inevitability … some old songs as well. Some you’ll like; some you won’t. But shit happens, y’know”, as Phil tells the Knebworth crowd.

And for fans of old Genesis, that’s your lot. Afterglow has gone. It now falls to Hold on My Heart from the new album to supply the emotional punch that Afterglow previously landed. It is a bit like asking a scrawny flyweight to go toe to toe with Muhammad Ali. It is not a contest of equals.

Even Los Endos, an exhilarating end-of-show staple since 1976, has gone. The latter part of the set is dominated by newer material, beginning with Domino and then, after the drum duet, I Can’t Dance. Truly, we are ending with a moment of bathos.

Yes, it is a seriously awful song with which to bring the main set to a close. Even worse, if that is imaginable, we are also forced to watch through our fingers as Mike and Daryl march around the stage in single file behind Phil. The riff may not be hard to play, but this is a manoeuvre that requires a considerable amount of dexterity, as they take care to ensure that guitar necks do not insert themselves anywhere anatomically inconvenient.

At last the torture is over and the band exit stage right, returning shortly afterwards for the encores, the first of which features two of the band’s biggest hit singles. Tonight, Tonight, Tonight is another opportunity for the audience to join in – “Oh-oh!” – before a nifty segue to Invisible Touch. The second encore – and the end of proceedings – is Turn It On Again, as it has been since 1983. The medley of pop classics from the last tour has gone; instead, Phil namechecks the band.

The final show of the tour was intended to be at the Royal Albert Hall in London on 16 November but an earlier concert in Wolverhampton was rescheduled to the following night. So it is in the improbable setting of Wolverhampton Civic Hall in the Midlands (capacity, roughly 3,500) that our story effectively ends.

The announcement that Phil had left the band came in 1996, though he says in his autobiography that he had made the decision more than two years earlier, citing the pressures of the We Can’t Dance tour as one of the contributing factors:

As we tick off the world’s enormodomes and super-stadiums, a thought sets in: do I really want this, this pressure, this obligation? Can I keep this up – the singing, the banter, the larger-than-life performances required – right through a gruelling summer schedule, all the way to an eye-wateringly gargantuan, outdoor homecoming show at Knebworth?

from Not Dead Yet by Phil Collins

The books referred to in this blog are:

Mike Rutherford The Living Years (2014)

Phil Collins Not Dead Yet: The Autobiography (2016)

Los Angeles 1986: Genesis Bootlegs

You can’t really argue with the statistics, can you?

The Invisible Touch album, released in June 1986, sold six million copies in the USA alone and was on the Billboard 200 chart for eighty-five weeks. The eponymous single was a US number one. Both single and album didn’t perform too shabbily around the rest of the world either. Nor did the singles released subsequently – four in the USA, all of which reached the top ten. And, according to Wikipedia, the accompanying ten-month world tour grossed around $60 million – that’s roughly $160 million in today’s money.

No surprise, then, that Mike Rutherford wrote in his autobiography that this was “probably our hottest moment in terms of commercial success”. The only questionable thing about that comment is the inclusion of the word ‘probably’. And yet it is impossible to talk about Genesis in the 80s without also mentioning Phil Collins and his phenomenal popularity as a solo artist at exactly this time.

When the Mama tour ended in late February 1984, Collins’ solo single Against All Odds (Take a Look at Me Now) had already been released in the USA. It reached number one (one place higher than in the UK) and was the first of seven US chart-topping solo singles (six more than Genesis achieved). His 1982 cover of the Supremes’ You Can’t Hurry Love had been a surprise hit on both sides of the Atlantic, but 1984’s Against All Odds began an extended period of extraordinary mainstream success for Collins that lasted into the following decade.

Easy Lover, a duet with Earth, Wind and Fire vocalist Philip Bailey, was another 1984 smash hit single, and his third solo album, No Jacket Required, went on to sell perhaps as many as twenty-five million copies, making it one of the biggest-selling albums of all time.

It’s no wonder that the chapters of Collins’ autobiography covering this mid-80s period are called Hello I Must be Busy and Hello I Must be Busy II: he was all but impossible to avoid, a workaholic and hit machine incarnate. In addition to producing albums for Bailey and his buddy Eric Clapton, he toured the world to promote the No Jacket Required album (including playing two nights at Madison Square Garden)…

…contributed drums to the Band Aid charity song Do They Know It’s Christmas? at the end of 1984 and then played at both Wembley Stadium (with Sting) and Philadelphia (with Led Zeppelin) at the Live Aid concert in July 1985…

…reached number one in the USA (again) with another duet – this time Separate Lives, with Marilyn Martin – guest-starred in an episode of hit TV show Miami Vice…

…and got married for a second time. (NB He admits in his autobiography that “large chunks” of the lyrics of the 1986 song Invisible Touch were written about his first wife, from whom he separated in 1980.)

Collins wrote in his autobiography that if ever he was going to quit Genesis to focus on his solo career “in theory this would be the time”. He was, in a nutshell, more popular than Genesis, who very obviously had not played at Live Aid, unlike a sizeable proportion of the top-tier acts, old and new, in the rock and pop universe.

Tony Banks, meanwhile, had released his second solo album in 1983 and was also involved in writing film music. Rutherford had formed the band Mike + the Mechanics in 1985, having decided that he no longer wished to release material as a solo artist following the release of his second solo album in 1982.

But Collins didn’t leave in 1985. He had missed the band’s “magical way of working in the studio”, he wrote later. So had the other two. Rutherford described the new album, which was recorded between October 1985 and February 1986 in the band’s home studio in Surrey, as “effortless to make”:

Phil had a little drum machine … and we’d start with a nothing-very-much loop and jam over it. Phil would sing whatever came into his head, and Tony and I would pile in fearlessly with any old chords and noise and racket. And out the songs came.

So, how does Invisible Touch measure up as a Genesis album? Okay, you can’t argue with the stats, but is it actually any good?

It isn’t rubbish, obviously – this is Genesis we are talking about, after all – but regular readers of this Genesis Bootlegs blog series will know that I am not a huge fan of the band’s 80s output: Abacab, Genesis (the 1983 album) and Invisible Touch sit comfortably at the bottom of my Genesis album ranking list. Indeed, I am not a fan of 80s music more generally, at least the mediocre fare served up by the rock titans of the 70s who continued on into the following decade.

And with its catchy chorus-driven arrangements, vacuous lyrics (“There’s too many men, too many people / Making too many problems / And not much love to go round”) and heavily processed sound – what the presenter of YouTube’s Classic Album Review show regularly refers to as “those 80s affectations” – Invisible Touch is very much an 80s album.

Perhaps even more to the point, at least three songs on the album – In Too Deep, Anything She Does and Throwing It All Away – would not sound particularly out of place on No Jacket Required.

On the other hand, plenty of Genesis fans disagree, citing in particular the album’s two longer songs – Tonight, Tonight, Tonight (8 minutes 53 seconds) and Domino (10 minutes 44 seconds) – as evidence of a residual prog-esque complexity in at least some of their music.

Well, possibly.

The – frankly gigantic – Invisible Touch tour began on 18 September 1986 in Detroit and ended on 4 July 1987 in London. It included no fewer than three North American legs (the first of which was made up of multiple nights at just seven venues) as well as shows in New Zealand, Australia, Japan and Europe – all in front of enormous audiences.

The opening North American leg included five nights at the legendary/iconic (choose your cliché) Los Angeles Forum, 13–17 October. For the purposes of this blog I used a bootleg I found on YouTube that is stated as coming from 14 October, the second night in LA. It is possibly a King Biscuit Flower Hour show, though this recording has none of the usual King Biscuit add-ons. (The excellent Genesis Movement website suggests that Collins’ dialogue from the King Biscuit performance comes from 14 October and 15 October.)

The setlist for this initial leg of the tour leaves us in no doubt that this is a show put together with the band’s massive new mainstream audience in mind. It has undergone an unprecedented – for Genesis – overhaul. The band play the entire Invisible Touch album, with the exception of just one song (Anything She Does).

This LA Forum setlist is typical:

Mama / Abacab / Land of Confusion / That’s All / Domino / In Too Deep / The Brazilian / Follow You Follow Me / Tonight, Tonight, Tonight / Home by the Sea / Second Home by the Sea / Throwing It All Away / Old Medley / Invisible Touch / Drum Duet / Los Endos / Turn It On Again Medley

Many of the songs from the previous two albums – Dodo/Lurker, Illegal Alien, Man on the Corner, Who Dunnit?, Keep It Dark, Misunderstanding and It’s Gonna Get Better – have been ditched to make way for the new stuff. What I labelled in the Philadelphia 1983 blog as Old Medley 1, which chopped and changed during the Mama tour but included early- and mid-period classics such as Eleventh Earl of Mar, Firth of Fifth and The Musical Box, has also vanished.

Nowadays we regularly see ‘legacy bands’ promoting a tour by organising the setlist around a classic album and playing it from start to finish, but playing an album in its entirety was far more unusual back in the 70s and 80s (Pink Floyd were an exception). True, the 1980 Duke tour featured roughly thirty or so minutes of back-to-back new music, but the collection of songs they played was originally conceived as a single self-contained piece of music, a Duke ‘suite’.

The decision to play almost everything on Invisible Touch means that the new setlist has a serious lack of balance to it, particularly the first hour or so. The track Domino begins a roughly forty-minute run of new music broken only by the inclusion of (the rather slight) Follow You Follow Me.

This particular recording sounds great, and the performances are as polished and professional as you would expect. Apparently, the band were being paid hundreds of thousands of dollars for some of these shows – and they don’t disappoint.

Then again, as the Britpop band Oasis (who are in the news at the time of writing this blog) proved more than once in their career (and indeed as Led Zeppelin – with somebody called Phil Collins on drums – proved at Live Aid), it really doesn’t look and sound great performing in a stadium when the band is below par for whatever reason.

And not to mention the immense logistical challenges associated with tours on this scale. The Pink Floyd guitarist Dave Gilmour and Floyd’s manager tagged along for several weeks to help them prepare for an upcoming and similarly ambitious Floyd tour. (The A Momentary Lapse of Reason tour ended up making even more money than the Invisible Touch tour.)

In fact, the performances are perhaps even more polished and professional than you would expect. Rutherford tells us in his autobiography that it was during this tour that he heard the news that his father had died. It was arranged that he would fly back to England for the funeral on 13 October and then fly back the same day to play in Los Angeles. At least some of the recording discussed here, then, is from the following night.

(Actually, the timeline he outlines in his book doesn’t seem to fit the facts. He writes that he received the news in a hotel in Chicago in the middle of a six-show run and that the funeral took place two weeks later. But their six-night residency at the Rosemont Horizon – just outside Chicago and presumably what he is referring to – was from 5 October to 10 October. LA was the very next stop on the tour, just a few days later.)

Anyway, back to the show. The newer material offers plenty of opportunities for the audience to join in, and frontman Phil is of course a dab hand at keeping them all entertained. One wonders what the LA crowd made of Collins’ reference – in his introduction to In Too Deep – to people “having it off”.

In truth, much of the between-song banter feels somewhat predictable by now: they are still, for example, riffing on the “Other World” theme before Home by the Sea, though this time asking the crowd’s assistance to levitate the venue rather than merely contacting the spirits as they did on the previous tour. And a comparison with the Wembley shows at the opposite end of the world tour suggests that there isn’t a great deal of variation from one show to another. Spontaneity is perhaps the first casualty of the stadium experience (with intimacy the second). Not that Genesis first-timers in 1986–87 would have been thinking any of this, I guess.

The primary nod to the old days – “Right, now for some of that really really really old stuff” – is a medley that begins, as Genesis medleys have done since their introduction on the Duke tour, with In the Cage, which segues into In That Quiet Earth from Wind and Wuthering and then the closing two sections of Supper’s Ready (from Apocalypse 9/8 onwards). In That Quiet Earth, in particular, sounds fresh, with an earthy (no pun intended) guitar sound and some outstanding interplay on the drums between Collins and Chester Thompson.

And then we immediately switch from the (very) old to the (very) new: Invisible Touch – the song that had got them to number one in the USA and catapulted them into the pop stratosphere. The show proper ends in familiar fashion with a drum duet that leads into Los Endos, the latter as thrilling as ever despite now being the end-of-show staple for a full decade.

The encore again finds the band opting for mass appeal. Turn It On Again, as on the Mama tour, incorporates a medley of its own, but this time one that is made up of snippets of pop and soul ‘classics’:

Everybody Needs Somebody to Love / (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction / Twist and Shout / All Day and All of the Night / You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’ / Pinball Wizard / In the Midnight Hour

It’s light, it’s stadium-friendly and it dials up the feelgood factor to eleven – but is it Genesis? Well, yes, of course it is – but anyone crossing their fingers for a blast of Watcher of the Skies or The Knife presumably left a tad deflated.

The Wembley shows were filmed and released on video, later rereleased as a DVD. It is well worth a watch, as long as those hideous 80s outfits they are wearing don’t scare you off. I am ambivalent about stadium shows for several reasons, but the Invisible Touch tour was undoubtedly a great spectacle, particularly once the daylight faded. And what a relief it is to see Tony Banks and his keyboards back in their proper place stage left after they were inexplicably moved to no-man’s land (ie between the two drum kits) on the Mama tour.

There were changes to the setlist for later parts of the world tour (from January 1987 onwards). In Too Deep and Follow You Follow Me were dropped completely and so the show itself became shorter. Afterglow also replaced Supper’s Ready in the main medley and Reach Out (I’ll Be There) by the Four Tops replaced All Day and All of the Night in the encore medley.

The changes were presumably to protect Collins’ voice. He wrote in his autobiography that he was having regular steroid injections as a short-term fix to get him through shows. (He also says that the injections led to health problems in later life, including brittle bones.) In addition, an adjustment to the order of songs gave the show a better balance between older and newer material.

Collins later described the Wembley shows as “tremendously atmospheric … easily the triumph of the tour”. The run of four shows (1–4 July 1987) was at the time a record, presumably just one of many that the band had set over the previous ten months and 112 shows. Rutherford put it like this: “Certain bands have certain years and 1986 must have been our year.”

And then… nothing, at least not in Genesis Land. Collins took a year off from writing and recording, instead starring opposite Julie Walters in a film about the Great Train Robber ‘Buster’ Edwards; Rutherford had further success with Mike + the Mechanics, notably the single The Living Years, which became a worldwide hit and a US number one early in 1989; Banks released an interesting but commercially unsuccessful album called Bankstatement in 1989.

Genesis did not come back together to record again until March 1991, nearly four years after the end of the Invisible Touch tour.

There is no official live album from the Invisible Touch tour, though recordings of Mama and That’s All (from Wembley) and In Too Deep (from the LA Forum) appeared on the 1992 live album, The Way We Walk Volume One: The Shorts.

As mentioned earlier, the final shows at Wembley were filmed and released on video (with, it seems, most or all of the footage coming from the middle two shows. The Old Medley was omitted). It was rereleased as a DVD in 2003 as Genesis Live at Wembley Stadium.

The final Wembley show and indeed the final show of the world tour – 4 July – was broadcast on the radio by the BBC and has long been widely available as a high-quality bootleg. Ten of the songs are now available on the BBC Broadcasts box set that was released in 2023.

In addition, The Brazilian – from 3 July – appeared as a b-side and is on Genesis Archives 2: 1976–1992, as is a version of Your Own Special Way from Sydney in December 1986 that was played with a live string section (local Musicians’ Union rules, it seems).

The books referred to in this blog are:

Mike Rutherford The Living Years (2014)

Phil Collins Not Dead Yet: The Autobiography (2016)

Reflections on Led Zeppelin Part 2

In Through the Out Door is Led Zeppelin’s eighth and final studio album, assuming we are not counting Coda, the compilation of previously unreleased tracks that was issued two years after the band had officially disbanded following drummer John Bonham’s death. It came out on 22 August 1979, three or so weeks after the first of their two Knebworth concerts and a whopping three-and-a-half years after their previous studio album, Presence.

Two initial points about In Through the Out Door: it is the first Zeppelin album that I bought at time of release and – unrelated to that, I think – I like it more than most Zep fans seem to. Check out any Zeppelin album-ranking video on YouTube and you will very likely find Coda propping up the list – that’s fair enough though, as I say, I personally don’t think of Coda as a genuine studio album (but it is an inspired title!) – with In Through the Out Door perched just above it.

(Next on the list – going in ascending order – will probably be Presence followed by Houses of the Holy, and then the first four albums, and finally Physical Graffiti in the top spot. For what it’s worth, I have done my own Zeppelin album ranking at the end of this blog.)

I can recall In Through the Out Door getting a scathing two-stars-out-of-five review in Sounds magazine. The reviewer was Geoff Barton, the standard bearer for heavy rock in a music paper whose journalists much preferred punk. (Incidentally, a young Sounds writer at the time who championed a hardcore subgenre of punk labelled Oi! was Garry Bushell, who later became the TV reviewer in tabloids like the Sun. Barton himself went on to edit the first issue of Kerrang!, itself an offshoot of Sounds.)

The paper had already panned two gigs that the band played in Copenhagen as warmups for Knebworth, and Barton’s album review dripped with schadenfreude. In the Evening was classic Zeppelin, he opined, but everything else (All My Love partly excepted) was an embarrassment. Barton, a huge Kiss fan, was taking a hefty amount of flak in the letters pages for the disco-influenced sound of the recently released Dynasty album, so he took particular delight in mocking the synth-heavy Carouselambra (winner of the oddest Zeppelin song title award), particularly the up-tempo synth solo that starts at roughly seven minutes in.

In Through the Out Door was, we read, a difficult album to record, with Jimmy Page at a low ebb physically and creatively (Chris Salewicz writes: “Frozen in his heroin addiction, Page had minimal input” – page 396) and Bonham, well, an alcoholic. But I like its bright, clean sound (with the exception of the vocals on Carouselambra which are so buried in the mix that the lyrics are all but indecipherable), and the extensive use of keyboards makes In Through the Out Door a much more varied and interesting listen than Presence (of which, more below). It is John Paul Jones’ most distinctive and impactful contribution to Zeppelin’s body of work since No Quarter six years earlier.

The opening In the Evening and side two’s All My Love are indeed excellent. I have never been an enthusiast for bluesy dirges (the dictionary definition of a dirge is ‘a mournful song’) and so I would probably have wrapped things up with the raucous Wearing and Tearing, which made a belated appearance on Coda, rather than I’m Gonna Crawl. But songs like Southbound Suarez and Hot Dog hold up against, say, Dancing Days and D’yer Mak’er (which gets the worst Zeppelin song title prize) on the much more highly regarded Houses of the Holy album.

That said, 1973’s Houses of the Holy, the band’s fifth album, is fated to sit forever in the shadow of the untitled fourth album. Over the Hills and Far Away and The Ocean are both great tracks, but The Grunge is nothing more than a filler – and not a particularly good one at that.

I find Thin Lizzy’s classic early studio albums – Nightlife (1974) to Bad Reputation (1977) – hard to listen to because my introduction to Lizzy’s music was their exceptional 1978 live album, Live and Dangerous. Ditto Zeppelin’s Houses of the Holy: three of its standout tracks – The Song Remains the Same, The Rain Song and No Quarter – are outshone by the versions that appear on the 1976 live soundtrack album, The Song Remains the Same, which was my introduction to Zeppelin. [Click to read Part 1 for more about this.] The moral of the story: don’t introduce yourself to a band’s music via a live album.

An album that I don’t appear to rate as highly as most Zep fans is their third one. Led Zeppelin III has its epic moments, of course: Immigrant Song and Since I’ve Been Loving You are majestic, and the gentler Tangerine and That’s the Way explore a folksy side to Zeppelin only hinted at on the first two albums. But other tracks – Friends, Out on the Tiles and Bron-Yr-Aur Stomp – are mediocre by Zep standards and the closing Hats Off to (Roy) Harper (no surprises that it is based on an old blues number) probably ranks as my least favourite song of theirs. Hey, Hey, What Can I Do, which was released as the b-side of Immigrant Song in the USA, would have been a much better pick.

Their first album, Led Zeppelin, also has its peaks and troughs. Good Times Bad Times, Dazed and Confused, Communication Breakdown and How Many More Times are excellent, but overall – and in spite of its hard-rock edge – the album draws too heavily on the band’s blues influences for my taste.

Led Zeppelin II draws liberally from the same well but nevertheless seems to offer something genuinely groundbreaking – a musical manifesto for a new decade (it was released in late October 1969). Eclectic and experimental, Led Zeppelin II sounds like a band still taking inspiration from but no longer constrained by their heritage. Or maybe the songs are just better.

Robert Plant once described himself to the journalist Cameron Crowe as “a golden god”. It is a rather tired cliché but the phrase ‘rock gods’ certainly captures some of the aura that surrounded Led Zeppelin – or, perhaps more accurately, that the band projected – in their heyday: irresistible, all-conquering, indestructible, and also distant and aloof, much like the ancient Greek gods that were once believed to reside on Mount Olympus, in fact.

A trope of ancient Greek tragedy was the concept of hubris – defined as excessive pride and dangerous overconfidence – followed by nemesis: punishment (by the gods), prolonged bad luck and ultimately downfall. It is a rich seam that has been continually mined during the last two millennia of storytelling. (At its simplest, think of any bighead-gets-his-comeuppance story.) And it is an interesting lens through which to observe Zeppelin’s unravelling in the second half of the decade.

The year 1975 appeared to start so well for them. Physical Graffiti – not just an ambitious, sprawling double album but also the band’s first release on their own Swan Song label – came out in February and was an instant critical and commercial triumph. Another high-grossing, hellraising tour of North America, with the band criss-crossing the continent aboard the aptly named Starship, was followed by a series of eagerly anticipated shows at Earls Court in London, originally three but extended to five by popular demand.

It is worth pausing briefly at Earls Court in May 1975 – Saturday 24 May 1975, to be precise – to listen in on some of Plant’s between-song chats with the crowd. (The concert is available as audio and video more or less in its entirety on YouTube and elsewhere.)

Introducing a show that will last well over three hours, Plant informs the audience that the band intends to take them “on a little journey of the experiences that we’ve had – the more pleasurable ones and some of the dark ones that have led to the music that has been so different in six-and-a-half years”. They may be rock gods, in other words, but it isn’t all paradise in paradise.

It is well known that Plant has long been reluctant to perform Stairway to Heaven, Zeppelin’s magnum opus in the eyes of many rock music fans. If at first he was fed up with the song’s ubiquity (he once donated $10,000 to a community radio station in Oregon in return for their pledge never to play the song again), the issue in more recent times seems to be Plant’s wish to distance himself from the song’s sentiments – “coming from the mind of a twenty-three-year-old”, he told one interviewer. (He was actually twenty-two when he wrote the lyrics).

According to Mick Wall, Plant only agreed to the song’s inclusion in the set list for the 02 Arena show in 2007 on condition that it was played midway during the set and without any fanfare. He also says that Plant had to be persuaded to leave in the “Does anyone remember laughter?” ad lib for the DVD release of The Song Remains the Same.

Plant was four years older by the time of the Earls Court shows, but he was still – or at least affected to be – the carefree hippie who sang of girls with love in their eyes and flowers in their hair. He says this as they settle on their stools at the front of the stage before playing Going to California: “This is a song about the would-be hope for the ultimate… erm… for the ultimate.” Whatever that means.

But for all this counterculture idealism, mammon was as important to Led Zeppelin as music:

It really is a treat to be playing in England again – or playing in Britain again. It makes us sound like foreigners, but somebody voted for somebody and everybody’s on the run. There’s very little people [sic] left in the business that we know to talk to anymore. We have to talk to passers-by on the street and cyclists and members of the public. This is for anybody who’s got any hope that everything can be okay in our wonderful country again. Everything can be grown from the seeds of goodness, right, and without becoming a prophet we ain’t doing too good at the moment.

Later, introducing Dazed and Confused, Plant adds:

So we’re really having a good time back in good old England. We gotta fly soon. You know how it is with Denis, dear Denis. Private enterprise. No artists in the country any more. He must be Dazed and Confused…

‘Denis’ refers to Denis Healey, the UK’s chancellor of the exchequer between 1974 and 1979. Income tax rates were much higher in Britain and across much of the developed world in the 60s and 70s than they are now. The incoming Labour government had increased the top rate of income tax from 75% to 83%, and the overall rate on investment income was as high as 98%.

Some wealthy celebrities became tax exiles, moving abroad temporarily or permanently to avoid paying tax in the UK, as did the members of Led Zeppelin (and Peter Grant). They were permitted to be in Britain for no more than thirty days during the 1975–76 tax year. Plant’s comment to the crowd at the end of the final Earls Court show was: “If you see Denis Healey, tell him we’ve gone.”

But tax headaches were far from the only problem by 1975. The rock-god lifestyle – sex, drugs, rock ‘n’ roll, more sex, more drugs, even more sex, even more drugs – was taking its toll. Cocaine and other illegal substances had always been freely available but now heroin, a much more destructive drug, was the narcotic of choice. Bonham (referred to by members of the Zeppelin entourage as ‘the Beast’, which was not meant as a compliment) was increasingly prone to bouts of alcohol-fuelled violence: Mick Wall describes him as a ‘droog’ on and off the stage. (Droogs were a gang of vicious thugs in the book and film A Clockwork Orange; Bonham had adopted their look on stage.) Stephen Davis, in his book Hammer of the Gods, writes of “a loose cannon, fully loaded and banging around the deck, destroying anything in his way” (page 258).

Worse was to follow. Plant and his family were involved in a serious car accident on the Greek island of Rhodes, and plans for yet another North American tour in August–September were abruptly cancelled.

Presence, released in March 1976, was the album that eventually emerged from the literal and metaphorical wreckage. Written in the autumn of 1975, it was actually recorded in less than three weeks, with minimal creative input from anyone except Page who, says Mick Wall, rushed to complete the album in marathon eighteen-hour-plus sessions fuelled by heroin (page 370).

True, Achilles Last Stand – the title an ironic nod, presumably, to Plant’s extended confinement to a wheelchair after the accident – is a frenetic ten-minute epic built around layered guitars and powerhouse drumming. But the album as a whole, featuring no keyboards and virtually no acoustic guitar, lacks the variety, ambition and moments of inspiration that make Physical Graffiti such a masterpiece.

Above all, the optimism that helped songs like Stairway to Heaven and Kashmir to soar – “Oh, father of the four winds fill my sails / Cross the sea of years” – has all but evaporated, to be replaced by a sense of isolation and despair. Los Angeles, for years the band’s playground, is now “the city of the damned”, and the frequent allusions to narcotics – “Paying through the nose”, “Got a monkey on my back” – are impossible to miss.

Tea for One ends the album on a suitably downbeat note, both musically and lyrically:

There was a time that I stood tall

In the eyes of other men

But by my own choice I left you woman

And now I can’t get back again

Led Zeppelin did not play live again until April 1977, the start of a shambolic North American tour that was cut short following the death of Plant’s five-year-old son, Karac, from a viral infection unrelated to the 1975 car crash. Their next – final – concerts in the UK were not until Knebworth in 1979, more than four years after their Earls Court triumph. Bonham died of alcohol poisoning the following year.

To conclude, here is my ranking of Led Zeppelin’s albums (worst to best):

8. Presence (1976)

7. Led Zeppelin (1969)

6. Led Zeppelin III (1970)

5. Houses of the Holy (1973)

4. In Through the Out Door (1979)

3. Led Zeppelin IV (1971)

2. Led Zeppelin II (1969)

1. Physical Graffiti (1975)

The books referred to in this blog are:

Stephen Davis, Hammer of the Gods, 1995 edition

Mick Wall, When Giants Walked the Earth, 2009 edition

Chris Salewicz, Jimmy Page: The Definitive Biography, 2018 hardback edition

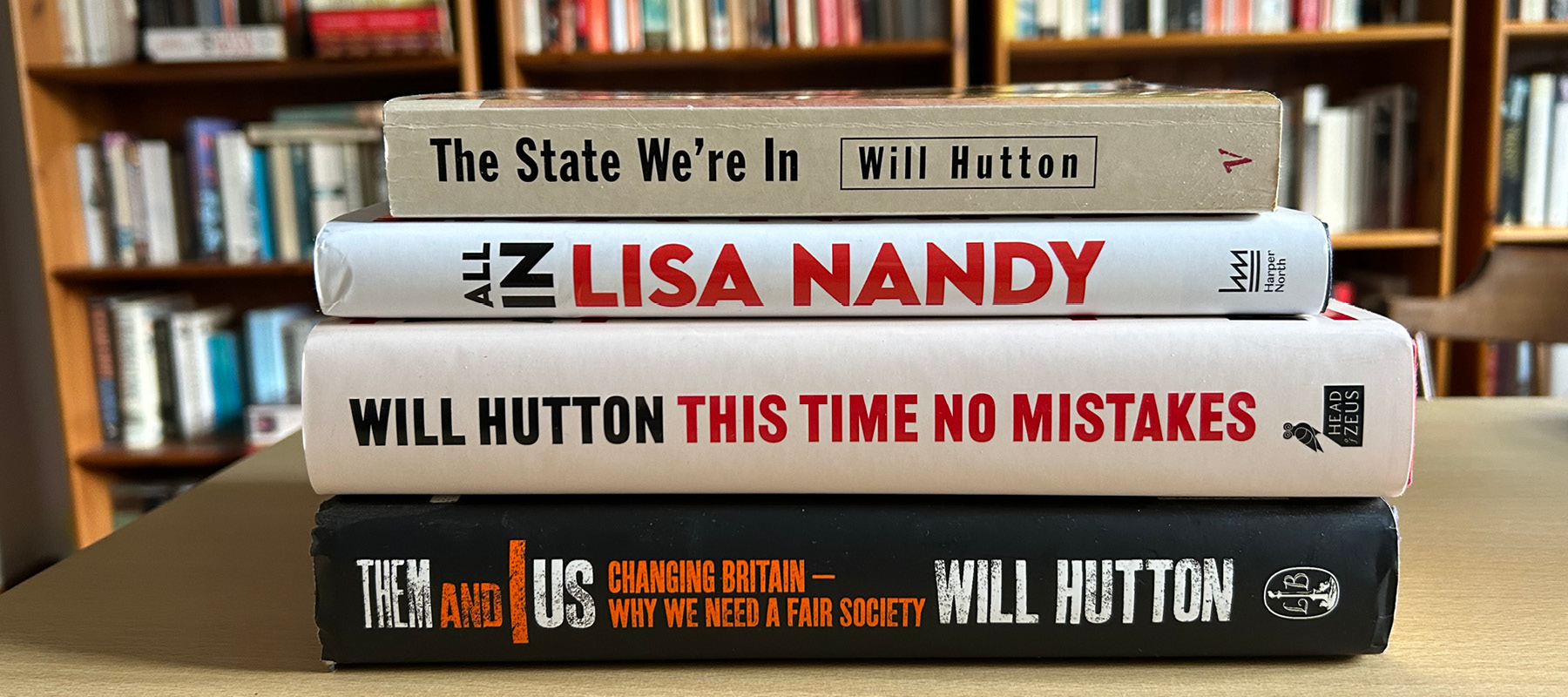

This Time No Mistakes

I uploaded this blog on the day of the 2024 general election, before the results of the exit poll were announced at 10pm.

If he were alive today, Benjamin Franklin would surely have said that nothing is certain in life except death, taxes and political parties refusing to be honest about taxes during an election campaign.

I wrote the bulk of this blog during the days leading up to the 2024 UK general election. Other than the staggering incompetence of the Conservatives’ election campaign, the main talking-point of the last few weeks has probably been the promise made by the two main political parties (joined by the Liberal Democrats) that, if elected, they will not put up any of the three main revenue-raising taxes: income tax, national insurance and VAT.

They have, in other words, embraced each other in a Faustian dance, making ludicrous assertions about the huge sums to be raised from cutting ‘red tape’ (see below for more about scare quotes!) and clamping down on tax avoidance and evasion to justify claims about fully funded plans that require no additional tax rises.

Unsurprisingly, the main manifesto launch week echoed with accusations of a lack of candour and of a failure to be honest with voters about the prospects for the economy, the state of our public services and the scale of the challenges the country faces. Paul Johnson of the Institute for Fiscal Studies – a respected independent voice – has talked of “a conspiracy of silence”.

And no shock, either, that – according to a British Attitudes Survey published last month – trust and confidence in government and politicians is at an all-time low.

Taxes and election campaigns

Let’s briefly rewind thirty years or so, to the beginning of 1992. The economy had been in recession for more than a year, the Conservatives were haemorrhaging goodwill after introducing the poll tax, and the party had ditched Margaret Thatcher, replacing her with the grey, technocratic John Major. Labour was narrowly ahead in the opinion polls and in with a chance of forming the next government.

In January the Conservatives unveiled their ‘Labour’s Tax Bombshell’ poster campaign, followed soon after by ‘Labour’s Double Whammy’ (a reference to more taxes and higher prices). The Conservatives went on to win a fourth term in the April general election.

A followed by B does not mean that A caused B, of course, and it would be ridiculous to pin an election outcome on just one factor. What is not in doubt, however, is the deep scars left by the 1992 defeat – and specifically those Tory tax attacks – on Labour’s collective psyche.

Labour as the party of high taxation is the go-to weapon in the Tories’ election arsenal, one wielded with relish by their many media cheerleaders as well. It is why in the 1997 election campaign Tony Blair and Gordon Brown went big on New Labour’s ‘fiscal responsibility’, promising to stick to the government’s existing spending plans for two years and not to put up income tax for the full parliamentary term.

Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves have been equally cautious. And yet the day after Labour’s 2024 manifesto launch, the front page of the Daily Express warned us not to “fall for Labour’s hidden £8.5bn ‘tax trap'”. The Times quoted Paul Johnson’s comment about a conspiracy of silence and pointed out that the Labour manifesto offered “no assurances on capital gains tax, fuel duty and tax relief on pensions”.

The Daily Mail’s headline was “What is Labour not telling us about tax hikes?” The Mail’s fondness for question marks in headlines reminds me of the adage associated with the journalist Ian Betteridge (though it predates him) that any headline ending with a question mark can be answered with the word ‘no’ – or, in this case, ‘nothing’ or, more likely, ‘not much’.

More broadly, the shallowness of the day-to-day party-political knockabout is why I would not describe myself as a political junkie. Why bother with Prime Minister’s Questions when you can be sure that the prime minister will not even attempt to address the questions put to him or her? (As a side-point, I have been surprised that, given his lawyer background, Keir Starmer has not been more agile on his feet during PMQs in exploiting Rishi Sunak’s evasiveness, almost always sticking to pre-prepared lines.) Why watch the BBC’s Question Time when you already know the script?

Short-termism is democracy’s Achilles heel, an inherent weakness most brutally exposed during election campaigns. Politicians either promise unachievable change in a ridiculously short timeframe (Sunak’s ‘Stop the boats’ pledge a good example, delivered very obviously with the polls in mind) or – the opposite problem – shy away from being frank with the electorate about the sort of remedies required to properly get to grips with the country’s problems (hence the current omertà on tax).

Take the book All In: How to Build a Country That Works by the Labour frontbench politician Lisa Nandy. I am a Nandy fan. Apart from being the MP for the town near where I live, she is smart, an assured media performer and someone with the ability to – cliché klaxon – talk human. It puzzles me why the Labour leadership have all but benched her.

(Nandy was briefly shadow foreign secretary, having come a creditable third in the 2020 Labour leadership election that Starmer won. She was later moved to levelling-up – actually a shrewd appointment, I thought, because her new role was shadowing Michael Gove, the Tories’ most effective minister – and then very obviously demoted to international development, though still in the Shadow Cabinet.)

Nandy’s book is an interesting enough read and – to steal the puff quote from fellow MP Jon Cruddas – she sets out a “positive agenda for change and renewal”. But, as a loyal frontbencher, she cannot and does not stray too far off script, if at all. For all her talk of starting afresh (page 3), Nandy’s thinking remains within the existing (Labour) paradigm.

Shifting the paradigm

It was not Ronald Reagan or Margaret Thatcher but Bill Clinton – champion, along with Tony Blair in the UK, of what came to be called ‘the third way’ – who proclaimed, in his State of the Union address in 1996, that the era of Big Government was over.

What we might think of as the Thatcherite–Reaganite worldview has set the terms of debate about public policy since the mid-1970s. It is the paradigm within which mainstream politics operates. Fear of the perception of governmental overreach – of so-called ‘nanny statism’ – limits what administrations of all hues are willing to contemplate.

The Overton window is a concept used in political science and denotes the range of policies voters will supposedly find acceptable. A policy that is outside the Overton window will not be accepted by the mainstream voting public. Any such policy may be widely seen as extreme or simply as impossible to achieve – and therefore any fundamental rethink of a policy or a set of policies (ie an approach or a strategy) will almost certainly require shifting the Overton window so that what was previously deemed extreme, impossible or unthinkable becomes acceptable, doable and achievable.

The concept is closely linked with the idea of common sense – ie with what instinctively seems right. The reason why Thatcher’s ghost still walks today is because her worldview became the dominant paradigm from the 80s onwards, setting the terms of debate and defining what was seen as common sense in politics and economics.

The political commentator Sonia Sodha has argued persuasively that, in economic policy, “the narratives of the political right are more compelling because they are more intuitive”. Thatcher’s claim that running one of the largest economies in the world was no different from running a household budget, though ridiculously simplistic (and, according to many economists, fundamentally wrong), was easy for voters to understand and seemed to make sense because it aligned with how they lived their lives.

Shifting the Overton window – changing the popular mindset – involves altering the terms of debate. But individuals do not form their worldview in a vacuum. Our thinking – about what is or is not right, acceptable, achievable – is heavily influenced by the media and other opinion shapers. For good or ill, much of the battle to reset the terms of debate needs to take place on this terrain. And it will take time.

Sodha has discussed the notion of the maxed-out credit card. It is a commonly used metaphor in the media and on the political right in arguments about government spending. It seems to make sense. It fits with our everyday experience of having to limit what we spend because we only have a certain amount of money and at some point it will run out.