Books, TV and Films, June 2021

4 June

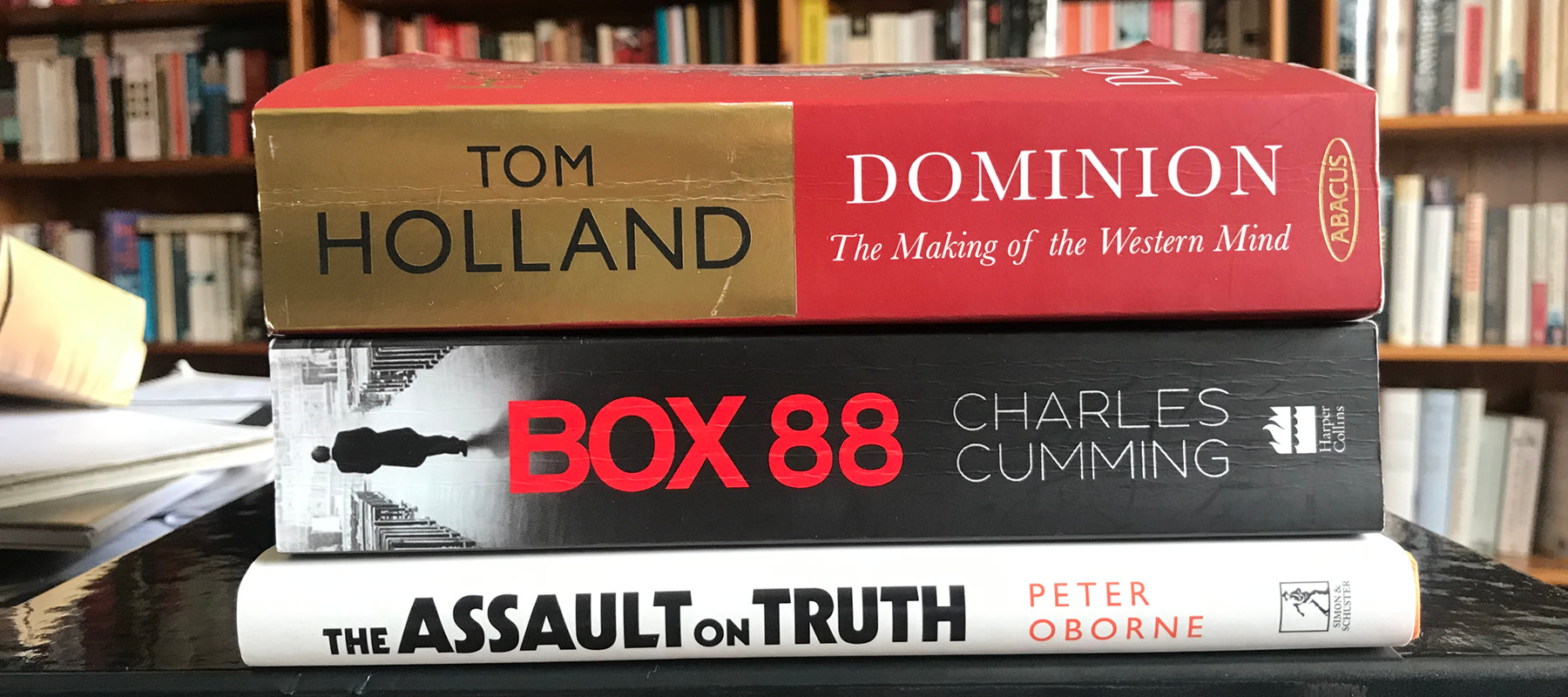

If Carlsberg did books, they would probably publish something like Tom Holland’s Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind. This is a BIG book — big in scale and scope, big in ambition, big in subject matter. In lager terms, much more of a flagon than a pint. It’s a book I immediately want to read again, this time at a far more leisurely pace so that I can enjoy more of the cascade of fascinating information that washed over me first time around. (On second thoughts, I really ought to read the same author’s In the Shadow of the Sword, which covers some similar ground, first.)

Dominion tells the story of the profound influence of religious belief, and primarily of Christianity, on how we live our lives, on how we think — our core beliefs, values and assumptions — and even on the language we use. As someone interested in the etymology of words, I was fascinated by Holland’s explanations of the origins of words and phrases that are part of our everyday language — how, for example, the ‘universal’ message of Christianity (katholikos in Greek) distinguished it from the ‘God’s chosen people’ exceptionalism of Judaism; and how the word ‘canon’, identifying a specific and limited number of chosen writings that supposedly contained the authentic message of Christ, derived from the Greek word for the chalked string used by carpenters to mark a straight line.

Holland has a telling eye for detail. The book itself is sweeping and panoramic, but each chapter opens with a specific time and place, perhaps somewhere familiar like Wittenberg c1520, perhaps somewhere remote and obscure (to this reader anyway) like Mount Gargano, a rocky promontory jutting out from south-eastern Italy into the Adriatic Sea, in the year 492.

It wasn’t always like this for me; I have written elsewhere about a blinkered and narrow-minded outlook that led to me focusing almost exclusively on modern political history. I am still working my way through Tom Holland’s back catalogue, but in books like Persian Fire and Rubicon he has helped open my eyes to the richness of ancient and early modern history.

As another advertising slogan didn’t put it, reassuringly brilliant.

8 June

A few months ago I watched The Odessa File; yesterday it was The Day of the Jackal. Both films are based on novels by Frederick Forsyth which I read as a sixth-former. I may already by that time have read books by Alistair MacLean, Jack Higgins and Jeffrey Archer (Shall We Tell the President? — a recommendation from my friend Chris), but the ‘Jackal’ book was memorable for its extraordinary attention to detail. I bought and read a new Forsyth novel, The Fourth Protocol, in 1984 because of my interest in CND and the politics of nuclear disarmament (the film features an impossibly young-looking Pierce Brosnan as the Russian baddie), but — as with Archer — Forsyth’s Conservative Party loyalties increasingly got in the way. I did read a few of his later novels — titles long forgotten, though The Fist of God was definitely one — which struck me as shallow thriller-by-numbers rubbish.

12 June

It was a bit of a shock to see BOX 88, the new novel by Charles Cumming, out in paperback when I visited my local Waterstones. It had been advertised on Twitter earlier in the week — the first I knew of it — and I had no idea that it came out in hardback in 2020. Cumming writes excellent spy novels. I first discovered him when I read The Trinity Six, a novel that played with the idea of a sixth Cambridge traitor alongside Burgess, Philby, Maclean, Cairncross and Blunt.

This is set to be a bumper few weeks of quality fiction reading for me. Robert Harris’ V-2 is out in paperback in early July, I still have Kate Mosse’s City of Tears to read and Sebastian Faulks has a new novel out in the autumn — apparently a sequel of sorts to Human Traces, my favourite book of his.

18 June

This is a month of football rather than TV and film watching. I was intrigued enough, however, to watch one of the TV Rebus dramatisations from the noughties. I know nothing about this series, except a vague awareness that John Hannah was originally (mis)cast in the role of Rebus before Ken Stott took over.

Three things struck me. First, ‘my’ Rebus and ‘my’ Edinburgh are of the ’80s and ’90s — I am up to Black and Blue, which was published in 1997 — in my reading whereas the setting of the episode I watched, Strip Jack, one of the earliest Rebus novels, first published (and therefore set) in 1992, has switched to the Edinburgh of the noughties, the time of filming. In these more enlightened times (and the second switch) is that Rebus has a female boss — no longer ‘the Farmer’ but a rather cold and aloof Gill Templer (in the books she and Rebus had previously had a sexual relationship).

The third (and main) difference, however, is the enhanced role given to DS Clarke, played by Claire Price. Whereas the book version of Rebus is a brooding, introspective loner — with much of the heavy lifting done by the narrator’s voice — in the TV series DS Clarke is essential as Rebus’ sidekick and foil. It is intriguing casting against type. Claire Price is physically slight and has a fresh-faced innocence about her that seems a world apart from the denizens of Edinburgh’s criminal underworld — I particularly associate her with the role of a rather demure and wide-eyed young woman from an episode of Poirot — but clearly DS Clarke has a steely, no-nonsense determination about her.

22 June

With the completion of the excellent Thomas Kell trilogy of novels — A Foreign Country, A Colder War and A Divided Spy — it looks as if BOX 88 is the start of another Charles Cumming story arc, featuring the characters Lachlan Kite and (possibly) Cara Jannaway. Like his other books BOX 88 is well plotted, exciting and believable. The spy novelists’ spy novelist is, of course, the incomparable John le Carré. Cumming’s writing, by comparison, though still packed with jargon and tradecraft, is easier for the non-specialist reader to disentangle.

Le Carré was a master at writing dialogue. Whether it was a stray enigmatic utterance, characters talking at cross purposes or an unfinished thought left to float off into the ether, le Carré used dialogue to help weave his webs of mystery, deception and obfuscation. Cumming’s approach to dialogue is a bit clunky at times. Take MI5 team leader Robert Vosse’s penchant for naming team members after characters in television shows — ‘Eve’, ‘Villanelle’ and so on — and the vulgar plain-speaking. Smiley, it isn’t.

“Are you lot taking the piss?” he shouted. “Villanelle’s in outer space. Cagney and Lacey went the wrong way on Piccadilly. What the fuck are you doing on Curzon Street? Get your arse back to the Playboy Casino. BIRD’s probably gone in there for a flutter with his pal from the Middle East.”

from BOX 88 by Charles Cumming

25 June

I have mentioned before that I don’t as a rule buy books about contemporary politics. They very quickly date. Peter Oborne’s book The Assault on Truth will be no exception — its subject matter is largely the Johnson premiership — but I decided that, in these days when memories are short, news stories are deliberately twisted and mangled like never before in modern times and the internet daily exposes us to endless new stories to absorb, it was important to own a physical copy, something to refer back to when today’s outrages are largely forgotten. (I had a pub conversation last week with two people prepared to argue that Johnson led the country well during the first stages of the pandemic.)

There is little in Oborne’s book that hasn’t been written about elsewhere, but he does a good job of setting out in a systematic way the evidence of lying by Boris Johnson (and his ministers and political cronies) and to a lesser extent Trump.

The most important parts of the book are where Oborne explains the damage that political lying — the catch-all term he uses to cover deceit and message-manipulation as well as the telling of out-and-out porkies — does to the public realm, to public trust in our political process, and to the norms, conventions and institutions that constitute the bedrock of our system of liberal democracy — principally parliament, the separation of powers, the impartiality of the civil service, freedom of speech and the rule of law.

He reminds us of the background to the seven Nolan principles (published in 1995 following a cash-for-questions scandal) governing standards expected in public life: selflessness, integrity, objectivity, accountability, openness, honesty and leadership. At the recent G7 summit, Johnson and President Biden resurrected the spirit of the wartime Atlantic Charter. We need something similar for the Nolan principles. They set the standard by which the actions and behaviour of those in public life should be judged, and they are as relevant today (in fact, even more so) as they were more than a quarter of a century ago.

I happen to be reading the book as the story has broken of health secretary Matt Hancock’s affair. It is an indication of the breakdown of integrity in public life that this is just the latest in a long list of scandals (and I don’t mean sexual scandals) that have demeaned politics in recent years. I am a believer that, ordinarily, a minister’s private life ought to be none of our concern. However, these are anything but ordinary times and this is not simply a private matter, even though several Cabinet ministers were initially wheeled out to claim that it was.

A government, led by a prime minister with strong libertarian instincts, has spent more than a year regulating our lives in a way unprecedented in peacetime, even down to dictating who we may and may not hug or have sex with. All, it says, for the public good. Trust and credibility are essential to the compact between government and people in a liberal democracy. In this case the government minister in charge must be seen to be following the tough, freedom-restricting rules and guidance he himself was responsible for introducing. Nothing undermined trust and the credibility of government messaging more during the first lockdown in 2020 than Dominic Cummings’ ridiculous Barnard Castle escapades and the popular perception that he had flouted the stay-at-home edict.

And then there is the ministerial code, the breaking of which is supposedly a resigning matter. Government ministers are expected, it says, to avoid even the appearance of impropriety. Gina Coladangelo was a non-executive director at the Department of Health, appointed by Hancock himself, her role an oversight one. Neither Hancock nor Johnson, it seems, felt that Hancock’s actions involved any appearance of impropriety and therefore this wasn’t a resigning matter. How times change. When Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands in 1982, the foreign secretary Lord Carrington immediately resigned. And in the same year, as Oborne reminds us, the home secretary and Thatcher confidant Willie Whitelaw — “every prime minister needs a Willie” — offered his resignation when an intruder broke into the Queen’s bedroom.

Postscript

I am preparing this blog for uploading on the day after Xi Jinping’s setpiece speech in front of 70,000 people in Tiananmen Square in Beijing to mark the centenary of the birth of the Chinese Communist Party. He said: “We have never bullied, oppressed or subjugated the people of any other country, and we never will.” Meanwhile, Hong Kong’s deputy chief executive is reported to have said in a speech: “While safeguarding national security, residents continue to enjoy freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly and demonstration, and others according to the law.”

This is not simple China-bashing. This week the prime minister Boris Johnson shamelessly tried to rewrite history by claiming that he sacked Matt Hancock as health secretary. In an excruciating and shameful PMQs on Wednesday, probably mindful that an outright lie in parliament could put him in difficulties, he repeatedly said that the Matt Hancock story had broken on the Friday and there was a new health secretary by the Saturday, citing this as evidence of swift and decisive action. He omitted to mention that his spokesperson had repeatedly briefed on the Friday that the PM had accepted Hancock’s apology and the matter was closed.