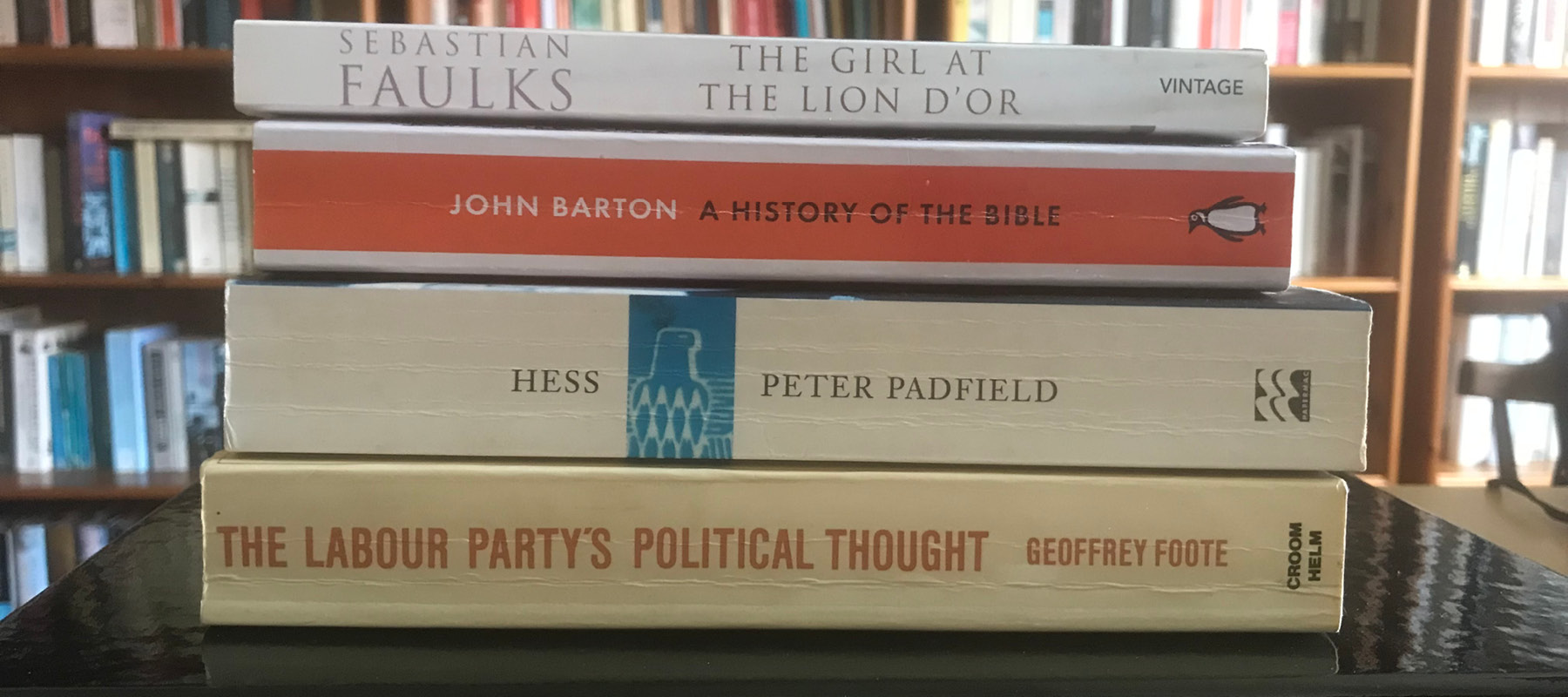

Books, TV and Films, April 2020

6 April

John Barton’s A History of the Bible: The Book and Its faith is proving an absolute treat. My interest in religion and belief systems has developed over the last decade or so, triggered — does this count as irony? — by reading Richard Dawkins. Anyway, last year I read the huge but hugely enjoyable A History of Christianity by Diarmaid MacCulloch. Professor Barton is another distinguished Oxford academic.

First of all, it was a pleasure to read — not just well written but also accessible. The contrast with the Michael Foot biography of HG Wells is telling. The Foot book required a great deal of background knowledge to make sense of it; Barton, on the other hand, goes out of his way to make his text accessible to the general reader.

Apart from its readability, this book is exactly what I look for when reading about something I don’t really know much about. Key words and concepts are clearly explained, even basics such as the meaning of ‘testament’, as in Old Testament. Important facts, ideas and arguments are covered succinctly, and revisited and reinforced.

Controversies and areas of disagreement (of which there are many) are set out before the reader. Barton does not shy away from telling us what he thinks, which I like. I turn the page confident that his conclusions and judgements are judiciously reached, and that I am being led along a tricky and complicated path by an expert guide.

9 April

Having planned in December to write something about the general election and the future of the Labour Party, I find that I have now written two blogposts about politics and still not really addressed what Labour ought to do next. Having read Mark Bevir’s book in January on the early years of British socialism and the ideas that were influential at the time when the Labour Party was founded, I have decided to re-read The Labour Party’s Political Thought: A History by Geoffrey Foote.

I bought the book at university, probably in 1986. I remember laughing about the front cover, which features photos of three men — Ernie Bevin, Tom Mann and Neil Kinnock. The photo of Kinnock, who was a new-ish Labour leader when the book was published, is twice the size of the other two, even though Kinnock only features in the final few pages.

I suppose there is an argument that it emphasises the connection between history and politics, but I can’t help thinking that’s it’s really a sales ploy by publishers to give history books an of-the-moment appeal.

13 April

It’s the Easter bank holiday weekend. Having just read John Barton’s history of the Bible, I am certainly noticing the many media references to biblical events, chiefly (of course) the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus. It’s striking how often these events are written about as if they were established historical facts.

In the absence of live sport on TV, I am working through a backlog of unwatched films and dramas. I have just re-watched Elizabeth with Cate Blanchett as the eponymous queen, Dickie Attenborough as a well-intentioned but deeply conservative William Cecil, Christopher Eccleston stuck on fast-forward as a sinister Duke of Norfolk and a brilliant Geoffrey Rush as Francis Walsingham. I have just started watching Mary Queen of Scots, which stars the wonderful Saiarse Ronan (definitely had to look up that spelling) and I have the Elizabeth follow-up, Elizabeth: The Golden Age, still to come.

I mentioned Mary Queen of Scots and The Favourite (which I have also just watched) in a blogpost called Fake History and Film. It is quite astonishing the liberties taken with the historical record in all of these films. Elizabeth, in particular, seems to have cut up a chronology of historical events into individual pieces and randomly reassembled them — either that or just made things up (assuming that she wasn’t really in a long-term sexual relationship with Dudley). Quite astonishing.

A leading article in today’s Guardian talks of revisiting ideas from Labour’s past, mentioning ethical socialism, William Morris and RH Tawney. Just what I have been doing!

18 April

Just finished the Foote book on the Labour Party’s political thought. Two immediate thoughts.

Books on politics age very quickly. That’s why I don’t often buy them. This is mainly a history of political ideas, but the concluding chapter (written in 1985) deals with then-current political thinking. It has not aged well. Events and developments are all viewed through a Marxist lens, and so his critical analysis just seems woefully out of date from the perspective of 2020.

Like many on the hard left, the author can’t quite bring himself to believe that the majority of the British people don’t subscribe to his idea of socialism: “[o]nly by risking a short-term unpopularity through industrial action could the long-term reward of electoral office be obtained,” he writes, in the context of union militancy at around the time of the miners’ strike of 1984. Yuk.

The second thing to note — something that would have completely passed me by until a few years ago — is the poor quality of the proofreading and copy-editing. To be fair, it’s presumably a fact of life for many small, cash-strapped publishers. There are a number of noticeable typsetting errors. More annoyingly, there seems to be absolutely no consistency with regard to capital letters. Style guides vary, but at least be consistent!

Sentences like this one are not uncommon:

The Social Contract … was finally destroyed by the discontent of the union rank and file in the winter of discontent in 1978-9.

Out-and-out spelling mistakes — as opposed to typographical errors — are (as far as I am aware) relatively unusual in books. They get the benefit of the doubt with ‘legitimatist’ — it should probably be ‘legitimist’ — but I was astonished to see Bevan’s famous quote about Gaitskell written as “a dessicated [sic] calculating machine”.

22 April

I finished binge-watching War of the Worlds last night — the 2020 Anglo-French production shown on the Fox cable channel: eight episodes (each of about 45 minutes’ duration) over three days. Set in the present, it’s nothing like the book, I don’t think, except for the basic fact that it’s about an alien invasion. It was bleak and properly dystopian. I was enjoying the slow unfurling of the story and the time taken on character development until I realised by about episode 6 that it wasn’t unfurling anything like quickly enough to reach a conclusion. Sure enough, the final episode sets us up for a second series. How disappointing.

Time for another Sebastian Faulks novel — The Girl at the Lion d’Or. It was published in 1989, so is very early (his first, possibly). I read it ages ago but, to be honest, I can remember hardly anything about it. The character names vaguely ring a bell, as do some seemingly incidental details. I note that a reviewer quoted on the back cover recommends it to fans of The French Lieutenant’s Woman, another novel that I read a very long time ago (possibly in the mid-’80s) and can remember very little about.

27 April

I finished The Girl at the Lion d’Or yesterday. It’s only 250 pages and didn’t take long; I had no trouble reading more than my 10% minimum daily target.

It’s the first of three Faulks novels set in France in the first half of the twentieth century — this one takes place in the ’30s, the final decade of the Third Republic. Just like On Green Dolphin Street, which I read last month, the novel is beautifully crafted: it’s a love story, but so much more as well. Every character, every event (however seemingly incidental), every exchange, every detail helps paint a picture of France in the years leading up to its collapse and national humiliation in May and June 1940.

The terrible impact of the 1914-18 war, particularly the psychological scarring left on the wartime generation, looms large. People are politically rudderless, losing faith in democracy and receptive to extremist solutions; the Jews are convenient scapegoats for the nation’s ills. Hartmann’s old family home is perhaps a metaphor for the Third Republic itself, the cracks in its structure gradually growing larger and its foundations undermined by the troubled builders’ shoddy workmanship.

Wonderful. Alas, my current read, a biography of the Nazi Rudolf Hess — Hess: The Fuhrer’s Disciple by Peter Padfield — most certainly is not. I don’t like giving up on books unless they are impenetrable or really, really boring. This is just a bad biography badly written, so I will plough on, especially as there is much I don’t know about Hess after his flight (as in ‘plane journey’, not ‘escape’) to Britain in 1941.