Books, TV and Films, February 2020

3 February

I finished A Divided Spy by Charles Cumming the other day. That means I managed to read four books in January, putting me comfortably ahead of my target. A nice balance, too, of fiction and non-fiction, academic and non-academic, challenging and ‘lighter’ reads etc.

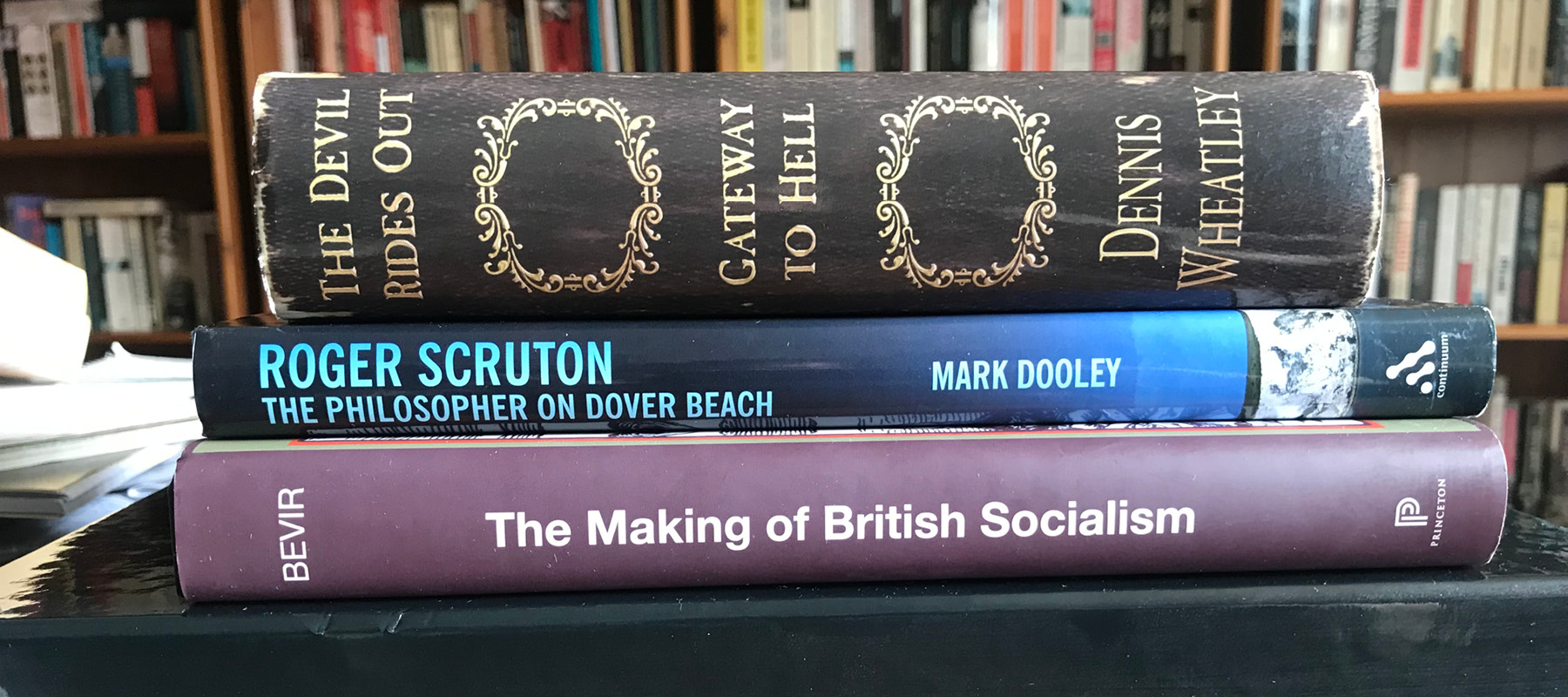

Reading Peter Ackroyd’s Dominion brought me back to thinking about the development of socialism and the origins of the Labour Party. I am re-reading The Making of British Socialism by Mark Bevir, a book I first read perhaps five years ago, possibly more.

It’s a tough book to get into, not really one for the general reader. It’s essentially a collection of academic papers pulled together into some kind of coherent whole. It is essentially a history of ideas but, as I say, written for an academic audience, with its talk of “retrieving alternative socialist pasts” and “narrating those pasts”. I gulped when I saw the sub-heading ‘Theory’, not really my thing when it comes to history. Welcome to “aggregate concepts”, “naive empiricism”, “reification” and so on.

8 February

The Making of British Socialism is proving an interesting challenge. It’s extremely repetitive in places — almost certainly due to its origins as a series of academic papers — which was annoying at first until I realised that the repetition was actually helping with the reinforcement of key ideas and aiding understanding.

The first couple of chapters were tough-going, with lots of terms and concepts unexplained. To take just one example, it assumed an understanding of the distinctions between popular radicalism, liberal radicalism and Tory radicalism.

As the book goes on, however, each of the key political ideas and concepts is being carefully unpicked, explained and analysed. One or two things still left me none the wiser — the discussion of German idealism, for example (nothing new there) — but most of the chapters have been rewarding and enlightening.

On a separate note, the BBC’s latest Agatha Christie adaptation — The Pale Horse (based on her novel of 1961) — starts tomorrow. A must-watch.

13 February

I finally finished the origins of British socialism book — a couple of days behind schedule. It’s been a busy few days, and I have found it difficult to keep to my 10% target.

It was definitely worth re-reading. At a time when politics is in a mess and the future direction of the Labour Party — even its very survival — up in the air, it was a useful exercise going back to the core ideas and values that animated progressives in the left’s early days. I particularly enjoyed reading about the ideas of the ethical socialists, who eschewed a class-based analysis, and economics and politics more generally, in favour of an approach based on spiritual renewal. Call it naive and impossible to achieve, but it’s a compelling vision of what the ideal society might be like.

One of the cable film channels showed To the Devil a Daughter last Friday, a 1976 film based on a Dennis Wheatley novel. It’s a somewhat controversial film for a number of reasons, and Wheatley disowned it. It’s rarely shown, certainly far less often than The Devil Rides Out, which I count as one of my all-time favourite films. I was meaning to re-read one of these two books before writing a blogpost on the subject, so this has sealed it. My next read.

16 February

Blimey. I thought Agatha Christie’s writing was dated, but Wheatley takes it to another level. The Devil Rides Out was first published in 1934. Like Christie’s Poirot, we’re mixing exclusively with the rich and privileged. Much of the characters’ wealth is obviously inherited, though Simon and Rex’s considerable incomes appear to be from finance and banking. Simon, we are told early on, is no longer living at his club. Max, meanwhile, is the Duke de Richleau’s ‘man’ — in other words, his butler. Indeed, butlers, maids, chauffeurs, cooks and nannies are an intrinsic part of this world. Globetrotting, too, is the norm: Rex, for example, has happened to notice a beautiful stranger called Tanith, who becomes central to the plot, in Budapest, New York and Biarritz in recent times.

The biggest shock is the use of language and the underlying attitudes it reveals. The meaning of words changes over time, of course, but it surely isn’t just poor writing craft that makes the use of the word ‘queer’ five times in the opening five pages seem alarming.

In Wheatley’s descriptions of the sinister guests at Simon’s party (it turns out they’re all satanists), the juxtaposition of each individual’s racial background with a list of their unpleasant characteristics is unfortunate to say the very least — the “grave-faced Chinaman … whose slit eyes betrayed a cold, merciless nature”; “a red-faced Teuton, who suffered the deformity of a hare lip”; a “fat, oily-looking Babu”.

To modern sensibilities, the most extraordinarily inappropriate exchange, however, goes as follows:

[Duke]: … he reminded me in a most unpleasant way of the Bogey Man with whom I used to be threatened in my infancy

[Rex]: Why, is he a black?

I kid you not.

20 February

I read about 80 pages of The Devil Rides Out last night — staying up late, as is becoming a habit with exciting novels, to finish the story.

The book improves considerably as it goes on. The well-known pentacle scene — when Mocata sends various manifestations of evil to claim back Simon — is excellently written and genuinely unsettling even for the modern reader. Up to this point, the later film roughly follows the book, but the final third is completely reimagined — presumably on cost grounds.

The Eatons’ daughter has been kidnapped by the satanists and is to be offered as a sacrifice in a black mass. In the film, the location of the mass is close by and easily accessible. In the book, on the other hand, our heroes are forced to traverse the continent of Europe. Handily, Richard Eaton has an aeroplane parked at the bottom of the garden. Cue breathless flights to Paris and then to an inhospitable mountain range in Greece for the final showdown between good and evil.

21 February

With the sad news of the death of philosopher Sir Roger Scruton, it felt right to pick out something of his as my next read. I have always found Scruton a curiously compelling figure. My politics are very different from his, though he is far from being an unthinking flag-waver for the right wing of the Conservative Party. His conservatism is grounded in his philosophical beliefs; unlike many on the right nowadays, he takes the ‘conserve’ of conservatism literally. He also writes beautifully.

25 February

I actually plumped for a book about Sir Roger Scruton rather than one written by him, though quotes from his many writings are used extensively. Roger Scruton: The Philosopher on Dover Beach by Mark Dooley analyses Scruton’s core ideas. Dooley is a fully paid-up Scrutonian, so there’s little in the way of critical engagement. Rather, the book serves as a useful introduction. It’s rather a slight book — 180 pages, including extensive end-notes — and hardly the “major study” promised on the dust jacket.

Organised into five chapters, it takes the reader through Scruton’s thinking on matters such as aesthetics, sexuality, religion and culture. Dooley returns repeatedly to notions of the Lebenswelt (our ‘lived experience’), the sacred, home and community, and belonging. He pays particular attention to where Scruton’s views clash with other thinkers, especially those on the left.

A useful read, helping me understand Scruton’s thinking better — and one that makes me want to search out more of Scruton’s output.

By the way, there was an excellent obituary of the historian Zara Steiner in The Guardian the other day, written by Sir Richard Evans. I first came across her when my professor recommended her Britain and the Origins of the First World War to me for my dissertation at university.

Evans is great. His recent obituary of Norman Stone was absolutely brutal. Ouch!