Queen Songs Ranked 80–61

It was the last album to make an appearance (at 82), and here three more classics from the consistently high-quality A Day at the Races appear in this magnificent selection of Queen songs. There is still one non-album track yet to feature, as well as three tracks from the Flash Gordon soundtrack. The album Made in Heaven makes its final appearance. Three tracks featured on Greatest Hits are listed, but nothing from Greatest Hits II.

Click here for details about how I compiled the list and to start from the beginning (number 185).

80. Pain Is So Close to Pleasure (Deacon/Mercury), A Kind of Magic, 1986

The best of the Freddie/John disco-funk collaborations, Pain has a distinctly Motown feel and some great falsetto vocal from Freddie. As so often, Brian’s guitar adds an unmistakeable Queen sound. The remix released as a single in North America is a salutary reminder that remixes are usually best avoided. Best moment: the solo, leading into the middle eight — “When your plans go wrong …”

79. I Go Crazy (May), b-side, 1984

Another of Brian’s rockier efforts that sounds as if it’s a one-take run-through with additional guitars on top. He’s actually quoted as saying that the others were “ashamed” of the song, hence its appearance only as a b-side. It’s certainly raw and unpolished, but that fits the mood of the song. Best moment: the ‘crazy’ ending from 3:09 onwards.

78. You’re My Best Friend (Deacon), A Night at the Opera, 1975

One of John’s gentler songs (presumably written for his then new wife Veronica) and his first hit single. The electric piano (played by John) was yet another addition to the Queen sound. The lush vocal harmonies are great. Compare the thick, warm drum sound to anything on the Jazz album. Best moment: any of the backing harmonies — but particularly from roughly 0:56 when lead and backing vocals split into separate channels.

77. Jesus (Mercury), Queen, 1973

A much-overlooked gem from the first album. Notable for Freddie’s Bible-themed lyrics and for great vocal harmonies. The centrepiece, however, is Brian’s extended solo, an early home for his experiments with guitar harmonies and a harbinger of future guitar wizardry. Bearing this in mind, Jesus is perhaps an example of what Brian has said was Freddie’s insistence in the early days that whoever penned the lyrics should be credited as the writer of the overall song (a comment he made, if memory serves, with reference to Liar). A version of Jesus was one of the songs recorded at the now legendary (sic) De Lane Lea session.

76. Who Needs You (Deacon), News of the World, 1977

A gentle Latin-tinged musical feel combines with acerbic, dog-eat-dog lyrics to great effect. When Radio 1 did their weekly album-chart rundowns in ’77, Who Needs You and Spread Your Wings were the two songs regularly played. The 2017-released early-take is also great. Best moment: the acoustic solo.

75. Rock It (Prime Jive) (Taylor), The Game, 1980

After his relatively sub-standard contributions to Jazz, Roger hit a real purple patch (he must have been writing and recording his excellent first solo album, Fun in Space, at much the same time). Rock It is (as the title suggests) a straightforward, no-nonsense rock song, but it benefits immensely from Mack’s production. It sounded even better live (on the rare occasions it was played). The rising synth from about 3:56 is not unlike the drone used at the start of their live shows at the time (also created by Roger, according to the Queen Rocks Montreal commentary). Best moment: the extended musical break from “We want some prime jive” at roughly 3:06.

74. Las Palabros de Amor (The Words of Love) (May), Hot Space, 1982

Just as Queen’s success in Japan had inspired Brian to write Teo Torriatte, so their ground-breaking South American tour in 1981 presumably inspired Las Palabros de Amor. The lyrics were also a comment of sorts on the Falklands War: Queen were massive in Argentina at the time, and at Milton Keynes Brian refers to this song (I assume it’s this one — he doesn’t actually name it) as “our song of peace”.

For the first time in five years, the band also appeared on Top of the Pops in a pre-recorded slot. Freddie and Roger are wearing tuxedos and Brian is sporting a tour jacket. It’s a hilariously stilted performance. Roger, as ever in these videos, looks thoroughly bored, making little more than a token effort to ‘play’ the drums and sing along. Freddie — again, as usual — makes a hopeless attempt at miming the vocal. John makes an excellent job of being John. Who knows what he is thinking.

Brian is in full action-man mode. It’s his song after all. Relying on memory, I wrote incorrectly that he mimed the synthesizer ‘swirls’ on Freddie’s grand piano. In fact, there’s a synth sitting on top of the piano. He alternates between ‘playing’ the two (not too sure what the piano bits are) before miming a bit of guitar later in the song.

Despite it’s more traditional sound (compared to their previous single, Body Language), Las Palabros de Amor was not a big hit, reaching only number 17 in the UK. It’s possible that the Spanish lyrics did not endear the song to the public at a time when Britain was effectively at war with Argentina.

Like their other Hot Space singles, Las Palabros de Amor was ignored for Greatest Hits II, despite it reaching the top twenty. It is also extraordinary that neither of the two singles released by June 1982 from Hot Space (not counting Under Pressure) was played live on the European tour (Body Language was added for the subsequent US tour). Almost unprecedented, in fact. Every other Queen single except You’re My Best Friend (which was added on later tours) was included in the live set at the time of its release.

Best moment: the guitar and “whoo hoo” at 3:23.

73. I Was Born to Love You (Mercury), Made in Heaven, 1995

Originally the lead-off single from Freddie’s solo album, this has an irresistibly uptempo beat, perfect for Brian’s guitars. It’s not hard to see why Queen + Adam Lambert introduced it into their set. Best moment: Roger’s drums at 3:50, heralding the long outro.

72. Drowse (Taylor), A Day at the Races, 1976

A somewhat left-field effort from Roger — and one of his best early-period Queen songs — the laid-back feel of the lyrics is perfectly complemented by the slide guitar, evoking long, lazy summer days (it was presumably written in the long hot summer of ’76, of course). The middle eight (“Out here on the street / We’d gather and meet …”) is particularly good. Best moment: Roger’s vocal at 2:22 — “the lights and the fun”.

71. Back Chat (Deacon), Hot Space, 1982

One of their more successful disco-dance efforts — again, sounding better played live. It’s baffling why this wasn’t chosen as the lead-off single from the album, as opposed to Body Language. Brian tells the story that he had to fight to get his ‘angry’ solo on the final mix: John originally wanted a hardcore disco-funk sound with no guitar at all.

Back Chat was their first 12” remix, actually one of the better ones, as most of them were decidedly ordinary. It’s possible that some of the additional guitar bits and vocal ad-libs are offcuts that didn’t make the final mix; even so, this extended version is nicely put together and worth a listen.

Best moment: the short synth break at 1:52, leading into the guitar solo.

70. Flick Of The Wrist (Mercury), Sheer Heart Attack, 1974

Freddie explores territory, musically and lyrically, that he returned to even more successfully with Death on Two Legs the following year. The guitar solo is appropriately vicious. Hard to believe that this was one half of a double-‘A’-sided single. Introducing the song at the filmed Rainbow shows, Brian refers to it as “the side which you haven’t been hearing on the Tony Blackburn show” — Blackburn was a Radio 1 DJ and household name at the time. Best moment: “Prostitute yourself he says / Castrate your human pride”.

69. Heaven for Everyone (Taylor), Made in Heaven, 1995

The best of the re-interpreted solo songs, this is a favourite with many fans. The pseudo-reggae feel is certainly an unusual sound for Queen. The version on the first Cross album is great too. Best moment: “What people do to other souls …”.

68. The Millionaire Waltz (Mercury), A Day at the Races, 1976

Successfully appropriating yet another musical style — this time a waltz — and overlaid with typically lavish arrangements, particularly from Brian. It’s always great to hear John’s bass prominent in the mix (in this case during the introduction). Despite not being released as a single, an abridged version of the song featured in the live-show medley for two years. Best moment: piano and guitar in waltz time at roughly 2:50. The sound of Brian’s guitar is quite exquisite at 3:19 to 3:24.

67. Doing All Right (May/Staffell), Queen, 1973

Thanks to the Bohemian Rhapsody movie, the whole world now knows that this was originally a Smile song. Listening to it afresh, it’s a delight to hear Freddie’s delicate vocal, particularly in the opening lines — a stark contrast to the macho style that became his trademark in the ’80s. On stage, Brian used his delay technique to great effect during the ‘heavy’ bits. (Check out the version played at Earls Court in 1977.) Best moment: the two heavy guitar breaks.

66. Need Your Loving Tonight (Deacon), The Game, 1980

Another of John’s hidden pop-rock gems (somewhat unfairly overlooked, nestling between two ‘classic’ singles). With its great opening riff, Need Your Loving… sounded particularly good on stage when it (briefly) featured towards the beginning of the set. It sounds like some nice acoustic guitar (from John, perhaps?) behind the main guitar. Best moment: what sounds like Freddie’s “let’s go” at 1:37 before the middle eight and Brian’s soaring solo.

65. Lily of the Valley (Mercury), Sheer Heart Attack, 1974

Delicate, beautiful and understated — almost a companion piece to Nevermore on Queen II (yet to feature in this list!). Typically gorgeous early Freddie lyrics, obscure and veiled at times, but poetical and enriched with literary and historical allusion —”my kingdom for a horse” referencing Shakespeare’s Richard III, for example. Best moment: the backing vocals at 0:52.

64. Fat Bottomed Girls (May), Jazz, 1978

In stark contrast to Brian’s usual lyrical preoccupations with leaving and absence, this is an in-your-face celebration of the rock-‘n’-roll lifestyle, which is lyrically more Roger Taylor territory. An edited version of the song was one half of Queen’s second double A-sided single, along with Bicycle Race (the first being Killer Queen / Flick of the Wrist and not We Are the Champions / We Will Rock You, which was not originally a double A-side in most parts of the world when it was released).

Unfortunately, the song is – for me, anyway – let down somewhat by the production. The guitar sound is rather dull and insipid, particularly the initial single-channel guitar after the opening a cappella chorus. The single version edits this bit out as well as fading the song itself out early. The (fairly dreadful) video was apparently filmed in Dallas, presumably during final rehearsals for their upcoming North American tour (Dallas was the opening gig).

On stage, on the other hand, Fat Bottomed Girls was magnificent, as shown by the version from Paris ’79 released on the Bohemian Rhapsody soundtrack and even more so the recording from Milton Keynes in 1982. There was a great ad-lib from Freddie at Milton Keynes: “You made an ass-hole outta me!” Its omission from the Live Killers album was one of several baffling editing decisions the band made when putting together the live album’s tracklist.

Best moment: Roger’s bass drum during the opening section of the song, before the whole band comes in.

63. A Human Body (Taylor), b-side, 1980

It’s quite astonishing that A Human Body didn’t make it onto The Game: it’s far better than Roger’s own Coming Soon and certainly an improvement on Freddie’s Don’t Try Suicide. It’s entirely possible that, in the latter case, band politics made it impossible for Roger to have three songs out of ten on the album. Some at least of the guitars are almost certainly played by Roger. Best moment: Roger’s vocals in the long outro from about 2:57 alternating between left and right channel.

62. Now I’m Here (May), Sheer Heart Attack, 1974

A somewhat unlikely choice as single (there are much more obviously chart-friendly songs on the album), this is — unusually for Brian — an upbeat reflection of life on the road, specifically America. ‘Peaches’ is apparently a reference to a girl he fell in love with over there. It worked brilliantly as a set opener on the Sheer Heart Attack world tour and became a staple of the live show until the end.

Best moment: the repeat effect used on Freddie’s voice (“Now I’m here / Now I’m there”), which during the 1974–1975 tour was cleverly exploited via use of a roadie on the opposite side of the stage dressed to appear exactly like Freddie.

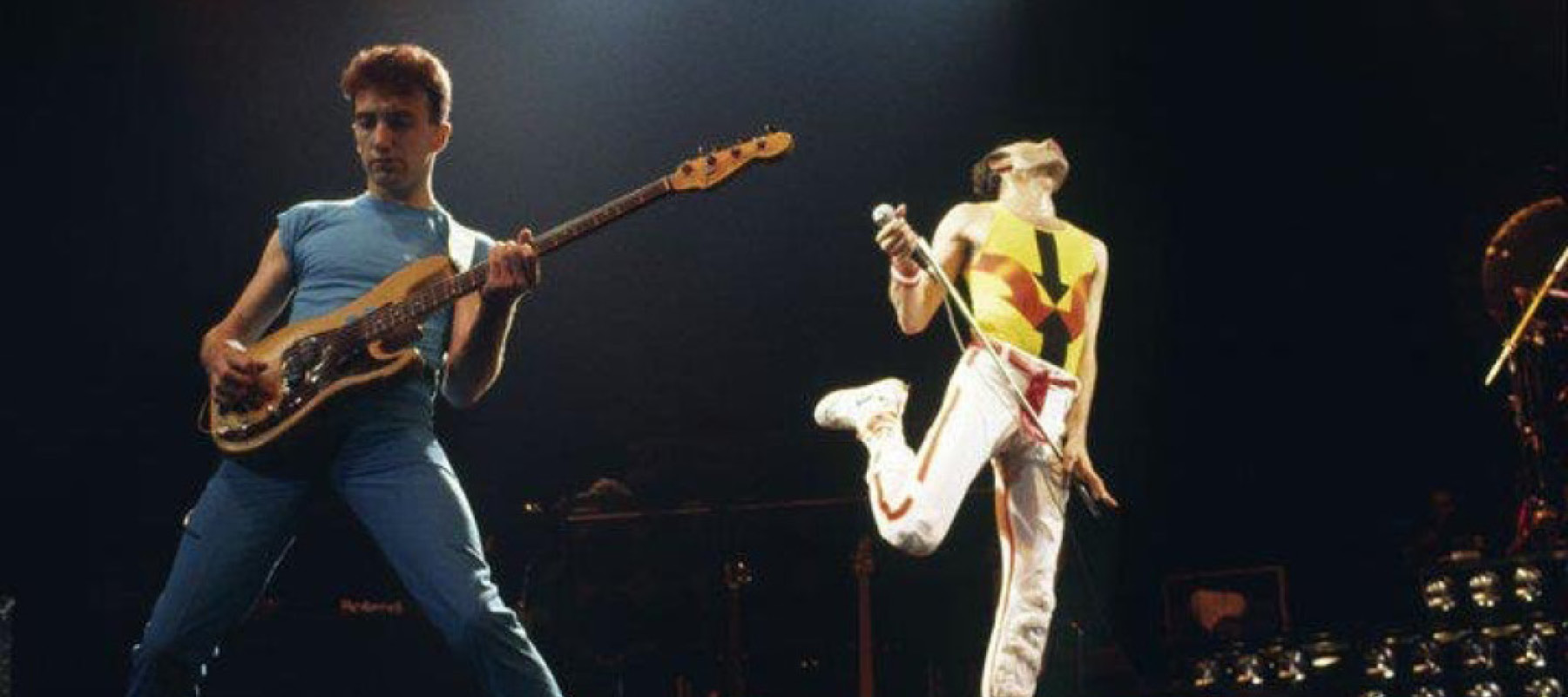

61. Tie Your Mother Down (May), A Day at the Races, 1976

Another raucous set opener courtesy of Brian — the easiest song to come onto the stage to, so he has said — and (also like Now I’m Here) an odd choice of single. One of the singles that didn’t make the Greatest Hits album, in the UK at least. It did, however, feature on Greatest Flix: unlike many of their ‘live’ videos, the video for Tie Your Mother Down is excellent, showcasing to the maximum their stunning light show at the time. Best moment: the harmonies on “all” when they sing “Give me all your love tonight” at the end of the chorus (for example at 2:04).

Queen Songs Ranked 100–81

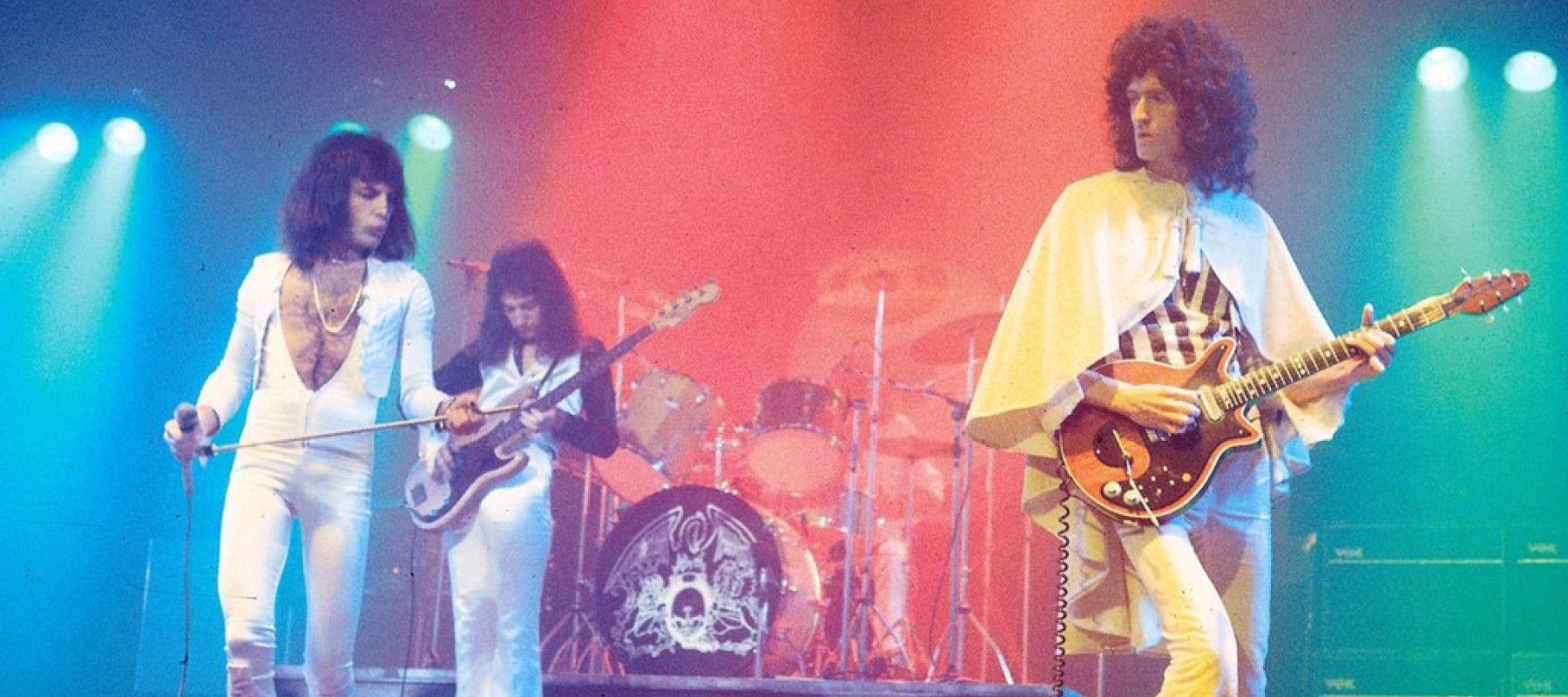

This is why Queen are the best band in the world: we’re just into the top 100 and there are some seriously great songs here. The first song from their fifth album, A Day at the Races, finally makes an appearance (at 82). Three undoubted Queen classics also feature in this particular selection, but three b-sides have yet to make their appearance!

Click here for details about how I compiled the list and to start from the beginning (number 185).

100. Action This Day (Taylor), Hot Space, 1982

One of many songs — particularly from the ’80s — that came to life on stage, Action is a typically uptempo Roger song, with both he and Freddie sharing lead vocal. Notable for a saxophone solo, it is unfortunately rather let down by a horrible drum machine sound. Best moment: the synth/guitar break at roughly 2:19, leading into the sax solo.

99. I Want To Break Free (Deacon), The Works, 1984

One of Queen’s most recognisable singles, the original version on The Works is actually rather sparse. John’s synth additions for the single version significantly improved the song. There is some great information about Fred Mandel’s contribution to the song — including a one-take synth solo — in this interview, starting at roughly 37:38.

One of their best ‘concept’ videos (as opposed to a ‘live’ performance of the song), it is of course fondly remembered for the Coronation Street pastiche. As a result, the audacious recreation of parts of Nijinsky’s ballet, Afternoon of a Faun, is almost always overlooked.

By the mid-’80s Queen were following the trend of releasing 12″ remixes — with patchy results. This one extends the outro in a harmless and mildly diverting way. Then, disaster: they insert a hideous More of That Jazz-style mashup of all the tracks from the Works album. No, no, no.

Best moment: the additional synth on the single version after the solo, starting at 2:35.

98. Modern Times Rock ‘n’ Roll (Taylor), Queen, 1973

Roger’s sole writing contribution to the first album and an early live staple towards the end of the set. The lyrics revolve around favourite Roger themes: rock ‘n’ roll and the coming generation. He takes lead vocal, though Freddie sang most of the song on stage, except for a raucous end section, when he and Roger shared vocal parts. Best moment: the guitar solo.

97. Gimme the Prize (Kurgan’s Theme) (May), A Kind of Magic, 1986

Probably as close to heavy metal as Queen ever got, this is a guitar tour de force from Brian. A song that suited Freddie’s much more aggressive ’80s vocal style. As on the Flash Gordon soundtrack, dialogue from the film is incorporated seamlessly into the song. Only the ‘fight’ sound effects mid-song date it a little. Best moment: the guitars at 0:25.

96. Play the Game (Mercury), The Game, 1980

Although the synth intro announced the end of the ‘no synthesizers’ era, this is actually a fairly by-the-book Freddie piano-based love song. The video is pretty awful, though it is highly praised in some undiscerning quarters (this comment once appeared on the official website: ‘It is an utterly enthralling four minutes, and among the band’s best loved and certainly most memorable films’). Best moment: the instrumental break at roughly 2:07 — as long as you ignore the image of the backwards-playing video that you’re visualising as you listen along.

95. Football Fight (Mercury), Flash Gordon, 1980

A hilariously camp and exhilarating slice of synth-driven pop. Best moment: the opening synth. The demo version — without synths — is great too. (It is one of the bonus tracks on the 2011 deluxe edition of the Flash Gordon album.)

94. We Will Rock You (May), News of the World, 1977

We Will Rock You has, of course, become iconic over the last forty years as a stadium anthem and as one half of a pairing with We Are the Champions. Indeed, it is always thought of as (in old money) a double A-side but in most countries, including the UK, it was originally the b-side to Champions.

Brian says that it was conceived specifically with live interaction with the crowd in mind. After the rich and complex textures of the first five albums, it opened the sixth album in dramatically sparse fashion. Performed live, it undoubtedly benefits from additional guitar and bass (most notably on Live at Wembley ’86) and, of course, the ‘fast’ version is another beast altogether — one of Queen’s best ever live songs.

93. Stone Cold Crazy (Queen), Sheer Heart Attack, 1974

One of Queen’s first songs (possibly emerging from Freddie’s ’60s band, Wreckage), though it only featured on the third album. Fast and furious, it was an early stage favourite. Surprisingly, it re-emerged in the Queen + Adam Lambert era, perhaps because it has been covered and played regularly by Metallica and so has gained a wider hearing beyond the traditional Queen audience. Best moment: the multi-tracked guitars from roughly 1:22.

92. My Life Has Been Saved (Queen), b-side, 1989 and Made in Heaven, 1995

It’s astonishing that the original version failed to make it onto the Miracle album: it is far superior to several tracks that made the cut. Both versions are great, though the later version omits some of Brian’s guitar. The lines “I read it in the papers / There’s death on every page” must have been unbearably tough for Freddie to sing: they are certainly unbearably tough to hear.

91. I Can’t Live with You (Queen), Innuendo, 1991

Brian reportedly said in 1991 that this had been a difficult song to mix; certainly, the version that appeared on Queen Rocks (with some instruments re-recorded) is much more muscular. Packed with great guitar. Best moment: “Through the madness, through the tears / We’ve still got each other for a million years” at roughly 3:10.

90. Let Me Entertain You (Mercury), Jazz, 1978

Another slice of fast-paced Freddie pop-rock, with typically lightweight though amusing, somewhat risqué lyrics (Mustapha, Bicycle Race, Let Me Entertain You and Don’t Stop Me Now — all Freddie songs from the Jazz sessions — have much in common). If nothing else, the line “We’re only here to entertain you” seemed to allude to Freddie’s desire to distance himself from what he had referred to as the band’s ‘too serious’ approach in the early days. Brian’s guitar is great throughout. The biggest head-scratcher was its placing on the original vinyl release of Jazz at the end of side one rather than as an opener.

Best moment: the lines “We’ll give you crazy performance / We’ll give you grounds for divorce”, with Freddie’s piano just audible in the mix.

89. Love Kills (Mercury), released 2014

The best of the Queen Forever compilation’s new tracks, this is a slowed-down version of one of Freddie’s best solo singles. The acoustic introduction works well, as does the big Queen sound at roughly 2:35. Queen + Adam Lambert performed a great version on stage in 2014.

88. Ogre Battle (Mercury), Queen II, 1974

After wind-like effects swirling left and right — the calm before the storm — the band unleashes a dense cacophony of sound and fury as backdrop for this tale of warring giants. One of Queen’s heaviest and most uncompromising songs, this “fable” of battling giants and mysterious auguries (“When the piper is gone and the soup is cold on your table”) features fantastical, Tolkien-esque lyrics from Freddie, typical of that era. The 1975–1977 tours featured Freddie appearing to magically cause explosions around the stage during the instrumental middle section. Best moment: Brian’s guitars at 2:02.

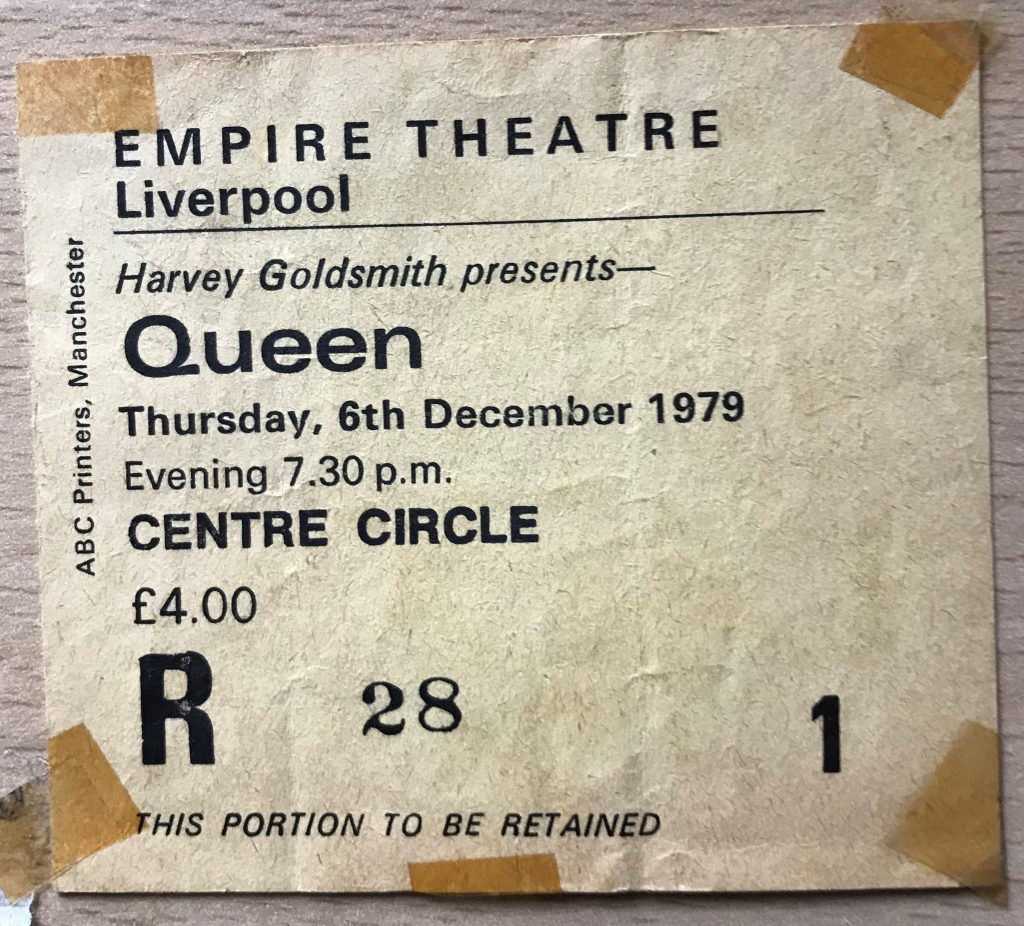

87. Crazy Little Thing Called Love (Mercury), The Game, 1980

Lightweight (“disposable”, to use Freddie’s own word) pop, famously composed in ten minutes in the bath and the last mega-hit that Freddie wrote. Released as a single in October 1979, this was the first time fans heard the clean, Mack-produced sound. The live version, the final section of which was more uptempo and guitar-heavy, is far superior. Best moment: though he was apparently kept away from much of the recording, it has to be Brian’s solo, played on a Telecaster.

86. Dead on Time (May), Jazz, 1978

Another Brian extravaganza, it is a shame that, like many of the songs on Jazz, it suffers from poor production, deadening the instruments (other than the awful drum sound), particularly the interplay of the multi-tracked guitars. The reason for the ‘Thunderbolt courtesy of God’ sleeve note. Best moment: the solo starting at 1:48.

85. Don’t Lose Your Head (Taylor), A Kind of Magic, 1986

Fast-paced and packed with interesting ideas, this is one of the best uses of electro-synth sounds by Queen, with the added bonus of a Brian solo at roughly 3:39. The title is of course a play on the method of execution of the ‘Immortals’ in Highlander.

84. Let Me Live (Queen), Made in Heaven, 1995

The best of the songs created from the fragments left behind by Freddie. Despite obviously having little to work with (hence the fact that Brian and Roger sing much of the lead vocal), they constructed a rousing gospel-influenced track, making use (for the first time) of outside backing vocalists to create the gospel-choir sound. Best moment: the verse sung by Freddie.

83. I’m Going Slightly Mad (Queen), Innuendo, 1991

Another song where lyrics and music complement each other perfectly, particularly John’s playful bass and Brian’s solo. The Noel Coward-esque lyrics are supposedly the result of a late-night competition to conjure up ever more ridiculous euphemisms for madness. Also one of their most creative videos, despite working under the most emotionally difficult of circumstances. Best moment: “Ooo ooo aaa aaa…” at roughly 3:01.

82. Good Old Fashioned Lover Boy (Mercury), A Day at the Races, 1976

A classic piece of Freddie piano-based pop with neat arrangements and multi-layered backing vocals. The words ‘old fashioned’ are not hyphenated on the back cover of the original album sleeve. A hyphen is, however, used on the inner-gatefold sleeve as part of the song title, though not in the lyrics themselves. It is unclear why an engineer (Mike Stone) was given a couple of lines to sing: Roger sang them on the partially re-recorded Top of the Pops version.

A follow-up single to Tie Your Mother Down, which barely scraped into the charts, its release coincided with British concert dates. It was packaged as Queen’s First EP, also featuring Death on Two Legs, Tenement Funster and White Queen. Best moment: Brian’s playful solo and the ‘countdown’ to dining at the Ritz at 2:17.

81. Dragon Attack (May), The Game, 1980

One of Queen’s better forays into dance-funk, primarily because there’s still plenty of guitar. Dragon Attack is one of the songs where Brian’s growing interest in (as he described it) making space for the rhythm arrangements to breathe is clearly evident. Great mini-solos, too, from Roger and particularly John. Best moment: the middle eight starting at roughly 2:40 (“She’s low down / Don’t take no prisoners …”).

Queen Songs Ranked 120–101

Twenty great songs, which nevertheless just miss out on a Top 100 placing due to the exceptional quality of the Queen canon. Some incredibly tough choices here, including the appearance of a bona fide Queen classic. Amazingly, any track from A Day at the Races is yet to feature. It’s their most consistently good album, in my view, if not necessarily their best — that’s another matter, which I have discussed elsewhere.

Click here for details about how I compiled the list and to start from the beginning (number 185).

120. Get Down Make Love (Mercury), News of the World, 1977

In some respects, the antithesis of the over-the-top, multi-layered production so typical of the earlier albums, this is Queen at their most stripped back: the utter emptiness at roughly 3:18 is truly arresting for any fan of the early material. Hot space, indeed. Also notable for Freddie’s risqué lyrics. The song stayed in the live set for five years, a showcase for Brian’s harmonizer effects and vocal gymnastics from Freddie. An early take (without harmonizer) released on the News of the World box set in 2017 is also terrific, with its feeling of spontaneity and exploration.

119. Made in Heaven (Mercury), Made in Heaven, 1995

At the time my favourite track from Mr Bad Guy, this reworked version makes the original sound somewhat insipid. A gorgeous melody and soaring vocals, given added emotional power by the Queen sound. It would arguably have been even better without the synth backing in the verses, instead giving the piano more prominence in the mix. Best moment: Brian’s guitar at 1:19.

118. Is This The World We Created…? (May/Mercury), The Works, 1984

An audacious way to end their ‘return-to-form’ album after the sound and fury of Hammer to Fall. Written months before Band Aid and Live Aid, of course, it is a deliberately simple and sparse arrangement. Lyrically, it is a long way from Freddie’s exhortation for us to drink champagne for breakfast, and for some the lines “Somewhere a wealthy man is sitting on his throne / Waiting for life to go by” will ring hollow. On stage, keyboard backing was added to the second verse, but the simplicity of the original arrangement works best. Best moment: “Is this the world we devastated / Right to the bone?”

117. Dancer (May), Hot Space, 1982

One of those songs — like Dragon Attack — that was pieced together from a jumble of semi-formed ideas. That’s not the only similarity between the two: both are guitar-heavy Brian creations, and both sit as track two on their respective albums. The programmed drums and synth bass sound horribly dated, but the multi-tracked guitars are, of course, great, particularly during the long outro from, say, 2:49. The German Wikipedia site tells us that the spoken words towards the end of the song are “Guten Morgen, Sie wünschten geweckt zu werden”, apparently best translated as “Good morning, this is your wake-up call”.

116. Mother Love (May/Mercury), Made in Heaven, 1995

Like most of the songs on Made in Heaven, Mother Love packs a mighty emotional punch. It is very likely the last song that Freddie ever recorded: too ill to complete the song, he did not live to finish the final verse, which Brian sang. The middle eight is immensely powerful and it is impossible not to be moved by the final section of the song featuring echoes of Freddie, beginning with Wembley ’86 and ending with Goin’ Back, one of his very first recordings as Larry Lurex and lyrically apposite.

The band adopted the policy of crediting all songwriting collectively to ‘Queen’ from 1989 onwards. Oddly — and perhaps owing to the uniquely harrowing and intimate circumstances in which it was written — Mother Love was credited to May / Mercury.

115. Procession (May), Queen II, 1974

How often does a song title so perfectly capture the mood of a piece of music? Regal, stately, majestic … a perfect way to open the album. A slightly different version features at the start of the 1973 Golders Green concert that was broadcast on the BBC and released as part of the Queen On Air boxset.

114. Misfire (Deacon), Sheer Heart Attack, 1974

The first of John’s songs to feature on a Queen album, this is a delightfully catchy pop song. Presumably he played all those guitars while Brian was recuperating in hospital and away from the studio.

113. Flash’s Theme (May), Flash Gordon, 1980

Cartoonish and tongue-in-cheek (“Flash — aah!”), it marries perfectly with the mood of the film, and Brian still manages to utter a perennial romantic truth: “No one but the pure in heart will find the golden grail”. Ming’s sinister utterance at the beginning — and the delivery by Max von Sydow — is pure genius: “I like to play with things awhile … before annihilation!”

The version released as a single – called Flash – is a significantly different edit of the song. It contains bits of dialogue from various parts of the film, including the iconic “Gordon’s alive?!”, a line Brian Blessed (who played the character Voltan) is still regularly asked to declaim to this day. Meanwhile, “Flash! Flash! I love you, but we only have fourteen hours to save the Earth!” must be one of the cheesiest lines in movie history.

112. Some Day One Day (May), Queen II, 1974

After Freddie’s death, the limitations of Brian’s singing were obvious, but here his sensitive voice is perfect for the dark and sombre lyrics (“No star can light our way in this cloud of dark and fear / But some day, one day…”) and a gorgeously affecting vulnerability is evident in his delivery of “we’ll come home”. It’s not the last time that Brian will sing of a longing for home. A fine blend of acoustic and electric guitar, and an early example of Brian’s penchant for guitar orchestrations. Best moment: the electric guitar backing each chorus and the ‘angelic’ chorus at the end of the second verse at 1:42.

111. My Melancholy Blues (Mercury), News of the World, 1977

An intriguing slice of introspective Freddie, evoking a drunken late-night, jazz-lounge feel. It features Roger on brushed drums and little or no guitar, except bass. A daringly downbeat song with which to close the album: they tried something similar with considerably less success with More of That Jazz the following year. Best moment: it’s just great to hear John’s bass throughout.

110. Too Much Love Will Kill You (May/Musker/Lamers), Made in Heaven, 1995

Undoubtedly a powerful ballad and a fan favourite from the Made in Heaven album, this is possibly a rare example (for Queen) of where less would have been more — ‘less’ in this case being something akin to the version on Back to the Light (the vulnerability in Brian’s voice captures the mood of the song, as does the acoustic solo at roughly 3:21). It’s a tough call. Both versions are great, and the line “I used to bring you sunshine / Now all I do is bring you down” is truly heartbreaking.

109. Seaside Rendezvous (Mercury), A Night at the Opera, 1975

A deliciously camp, music-hall-inspired vaudeville pastiche, showcasing the versatility, inventiveness and sheer audacity of the group — Freddie, in particular. Best moment: the ‘instrumental’ interlude.

108. Another One Bites the Dust (Deacon), The Game, 1980

Adored by many and sung by millions in sporting stadiums to this day. To some, it is the song that tempted Queen into thinking they could conquer the disco-dance world and led directly to their musical nadir — Hot Space. The bassline is certainly memorable, the arrangements are undeniably sparse and the drum sound is bone dry, but it’s worth remembering that this was not their first foray into this musical territory (its antecedents can be heard in Get Down Make Love and Fun It). Nor was it originally marked down as a single; Roger tells the story that it was Michael Jackson who persuaded the band to release it.

The Dust scene in the recording studio in the Bohemian Rhapsody biopic is unintentionally hilarious: Jim completes his paperwork in the corner as the band bicker, John produces his killer bassline, plucking a polished set of lyrics out of the ether for Freddie to sing, and another Queen classic is born. Best moment: the opening da-da-dum-dum-dum.

107. Put Out the Fire (May), Hot Space, 1982

Brian’s anti-gun song — a relatively rare chance on Hot Space for the band to rock out. A strong riff and a scorching guitar solo, Put Out the Fire is perhaps marred only by the jarring ’80s drum sound and by the rather shallow and simplistic first-person lyrics (again, typical of ’80s sensibilities, or lack thereof). The listener cannot help but feel that the writer of White Man might have found a more elegant way to convey his laudable message. Or maybe that was the point. Best moment: the opening of Brian’s solo at 1:58 and the rhythm guitar beneath it.

106. It’s a Hard Life (Mercury), The Works, 1984

Another of Freddie’s piano-based meditations on the vicissitudes of love (à la My Melancholy Blues and Jealousy), the piano-guitar interplay is reminiscent of the live version of White Queen and the general feel is of the early albums (a huge compliment!). Bits of the song are apparently based on an aria from the opera Pagliacci by Leoncavallo.

The song was included in the live set during the Works tour but arguably didn’t work as well on stage as, say, Play the Game had done. Best moment: Freddie’s stunning operatic opening — “I don’t want my freedom …”

105. The Kiss (Aura Resurrects Flash) (Mercury), Flash Gordon, 1980

Short and sweet, indeed, with gorgeous, gorgeous falsetto from Freddie.

104. In the Lap of the Gods (Mercury), Sheer Heart Attack, 1974

Although at heart a relatively by-the-numbers piano-based song, it is packed with quirky arrangements (the backing vocals are extraordinary) and features a truly ‘goosebumps’ opening — a electrifying way to open side two of the original vinyl release. Best moment: that opening…obviously.

103. Leaving Home Ain’t Easy (May), Jazz, 1978

Another of Brian’s songs about absence and longing, this time set to a nice acoustic backing. The treated vocals in the middle-eight section to represent the abandoned partner’s forlorn pleas — “Stay, my love …” — are great. Best moment: the multi-tracked vocals at 0:52 — “endless games”.

102. Lazing on a Sunday Afternoon (Mercury), A Night at the Opera, 1975

Audaciously positioned between the snarling beast that is Death on Two Legs and the powerhouse I’m in Love with My Car, this is yet another deliciously camp and bohemian slice of Freddie whimsy.

101. In Only Seven Days (Deacon), Jazz, 1978

A light, slight but nevertheless classy effort from John, with narrative-style lyrics a million miles away from the cold cynicism of If You Can’t Beat Them and Who Needs You. Best moment: the piano intro.

Queen Songs Ranked 140–121

This is starting to get hard now. Although we are still some way off the top 100 — or even the halfway point — there are no ‘fillers’ here: this collection is made up of twenty good, solid Queen songs. Some of them are what I would categorise as nearly-but-not-quite: there’s definitely something there, but the overall song doesn’t quite make it to the stratosphere. As you would expect, most of the non-album tracks are now accounted for … though by no means all.

Click here for details about how I compiled the list and to start from the beginning (number 185).

140. Calling All Girls (Taylor), Hot Space, 1982

A ‘hybrid’ guitar sound (sort of semi-acoustic), built on an uptempo beat, drives this song along — it sounded even better performed live (it featured in the set list for the ’82 US and Japanese tours – a version recorded at the Seibu Lions Stadium in Japan in November 1982 is on the deluxe edition of Hot Space). Calling is, however, let down somewhat by bland lyrics and puerile humour (assuming that it’s the sound of a record needle we hear at roughly 1:43 ‘scratching’ the vinyl). Best moment: the guitar in the chorus, for example at 0:55.

139. Delilah (Queen), Innuendo, 1991

A lightweight slice of Freddie-inspired whimsy with a playful synth-led tempo. Nice guitar from Brian, especially mimicking the miaow of a cat. Sometimes, something seemingly incidental and buried away in the mix just captures the ear — here it’s the piano at 0:25. Not one of Roger’s favourites, he is on record as saying.

138. You Don’t Fool Me (Queen), Made in Heaven, 1995

More than a decade after the release of Hot Space, this is one of Queen’s better efforts to capture a ‘disco’ sound (not least because of the absence of programmed instrumental backing). It is nevertheless immeasurably enhanced by terrific guitar from Brian, bringing to mind the Eddie Van Halen solo on Michael Jackson’s Thriller album. Best moment: the scorching guitar at 2:43.

137. Son and Daughter (May), Queen, 1973

A real spit-and-sawdust, blues-infused effort from Brian, this was a different beast on stage (and will feature a lot higher in my rankings of Queen live songs), a showcase for his guitar solo before Brighton Rock came along. The lyrics are frankly a puzzle. Listen carefully and there’s some great bass from John. ‘Live’ versions of the song featured on two BBC sessions, one of which includes a great of-its-time spoken line from Roger: ‘steel yourself — this is valid’.

136. Scandal (Queen), The Miracle, 1989

One of the better efforts from the Miracle sessions (and one where the synth treatments enhance the song for once), Brian’s screaming guitar captures the pain in the lyrics. Best moment: “It’s only a life to be twisted and broken …” at 2:12.

135. Sweet Lady (May), A Night at the Opera, 1975

Another of Brian’s rockier efforts, this has a great opening riff (sounding even better when played live), solo and frantic outro. The lyrics were mocked by ‘Roger’ in the Bohemian Rhapsody movie during a band ‘tiff’. Best moment: the guitars at 1:57

134. Khashoggi’s Ship (Queen), The Miracle, 1989

After a false start with Party, Khashoggi’s Ship — real drums, raw guitar, no unnecessary synth treatments — brings The Miracle to life, marred only by the interlude at roughly 1:30. Like some of the b-sides from the Miracle sessions, it sounds like it might have been recorded in a single take (which is not a criticism).

133. Jealousy (Mercury), Jazz, 1978

One of Freddie’s piano-based reflections on the pain of love, it also features great bass from John. Oddly enough, Brian’s brief acoustic contributions seem a little out of place. Best moment: John’s high bass notes at 1:38.

132. The Night Comes Down (May), Queen, 1973

Remarkably, it is the original demo from the legendary De Lane Lea session that made it onto the first album, as the band supposedly felt they were unable to improve on the feel of the song in subsequent takes. Now remastered, of course, it sounds great — such a mature sound, with typically dark and introspective Brian lyrics. Best moment: the end of the song, building to an unbearably tense climax.

131. Soul Brother (Queen), b-side, 1981

Although this sounds like a tongue-in-cheek, one-take throwaway, it is actually surprisingly effective and an unexpected bonus when Under Pressure was released. It’s the sound of the band enjoying themselves and each other’s playing.

There is a widely quoted comment attributed to Brian from 2003 in which he says that Freddie surprised him one day in the studio, saying that he (Freddie) had written a song about him (Brian). In the same quoted remarks, Brian also seems to link Soul Brother to the Game sessions (meaning 1979 and/or 1980) and this has become widely accepted (it is stated as a fact in the official lyrics book, for example). In fact, the lyrical allusions to Flash Gordon and Under Pressure very strongly suggest that Brian is mistaken on this point and that Soul Brother is from the Hot Space sessions, probably recorded at roughly the same time as Under Pressure in the second half of 1981.

Best moment: “When you’re under pressure …” at 1:20.

130. Cool Cat (Deacon/Mercury), Hot Space, 1982

With a suitably relaxed and laid-back sunny-days vibe, this is by far the best of the John & Freddie funky collaborations. John’s bass is fabulous and Freddie’s vocals are great too. The version with Bowie’s incidental vocals has rightly not seen the official light of day.

129. The Miracle (Queen), The Miracle, 1989

A classic nearly-but-not-quite song. On the one hand, satisfyingly complex arrangements (and a song that Brian often raves about), and a departure from the standard song structure. On the other hand, embarrassingly utopian, peace-on-earth lyrics (“That time will come / One day you’ll see / When we can all be friends”). Best moment: the closing minute or so, starting when John’s bass kicks in at 3:49 (and despite those final lyrics!).

128. A Winter’s Tale (Queen), Made in Heaven, 1995

It’s easy to see why there is a ‘cosy fireside’ remix (referencing a line in the song). For all its charm, A Winter’s Tale‘s real emotional power undoubtedly comes from the knowledge that Freddie wrote the lyrics in the face of approaching death. The lines are a bit clunky in places; under normal circumstances, they would surely have been edited and polished somewhat. Nevertheless, this is a far more satisfying seasonal song that their ‘official’ Christmas single, Thank God It’s Christmas. Best moment: “It’s all so beautiful / Like a landscape painting in the sky” at 2:49.

127. All God’s People (Queen/Moran), Innuendo, 1991

Apparently, this song was originally intended for the Barcelona album, hence the writing credit for Mike Moran. It’s very obviously two interesting song ideas spliced together (a technique they had used before — with Breakthru, for example). Best moment: when ‘Part 2’ kicks in at roughly 1:49.

126. Fight from the Inside (Taylor), News of the World, 1977

As shown by the demo version released in 2017, this is almost exclusively Roger, including lots of his trademark riffs and vocal sounds. The instrumental version, also released as part of the News of the World box set, is great. Best moment: the guitars bouncing around the mix, for example during the introduction.

125. Headlong (Queen), Innuendo, 1991

Obviously, a favourite guitar riff of Brian’s (he references it on stage to this day). One of those songs where the lyrics perfectly capture the mood of the music (and vice versa). Best moment: a toss-up between the sound of Brian’s guitar at roughly 2:45 and “Oop diddy diddy / Oop diddy do”.

124. Sheer Heart Attack (Taylor), News of the World, 1977

Apparently written at the time of the Sheer Heart Attack sessions in ’74, it would be interesting to hear a demo recorded at that time, as this ’77 version comes close to a full-on punk sound (an obvious response from Roger to the then-current music scene). The rhythm guitar on the demo version released in 2017 sounds more natural than on the final version.

123. Mad the Swine (Mercury), b-side, released 1991

An unexpected delight on its eventual release some thirty years or so late, Mad the Swine comes from the earliest sessions but failed to make it onto the first album. Another example of Freddie’s penchant for Bible-inspired lyrics from that period. That apart, it’s hard to envisage where it might have been positioned on the Queen album — certainly Roger’s percussion is more audible in the mix than on other songs of the time — or what it might have replaced. Best moment: the wonderful break at roughly 1:38 (“And then one day you’ll realise …”).

122. If You Can’t Beat Them (Deacon), Jazz, 1978

One of John’s hidden gems, this is a great guitar-led song, which really came to life on stage, though it was unjustly omitted from Live Killers. Best moment: the multi-tracked solo and the long outro.

121. Tenement Funster (Taylor), Sheer Heart Attack, 1974

All the usual Roger trademarks are here, lyrically (girls, growing up, cars and rock-‘n’-roll) and musically — it certainly sounds like Roger on rhythm guitar, though the soaring guitar solo is surely from Brian. Best moment: the aforementioned solo, following on from “I’ll make the speed of light out of this place”.

Queen Songs Ranked 160–141

Plenty of material here that is good but just rather ordinary by Queen’s exceptional standards. Another couple of singles feature, as do some of the better non-album b-side tracks. With numbers 185 to 141 now complete, only tracks from the first album and A Day at the Races have yet to feature anywhere on the list.

For details about how I compiled the list and to view numbers 185–161, scroll to the bottom of the page.

160. Dreamers Ball (May), Jazz, 1978

Another nod to America from Brian — this time the milieu is the New Orleans jazz scene — Dreamers Ball (the title appeared on the original Jazz album without an apostrophe; sometimes, as on the Live Killers sleeve, it is displayed as Dreamer’s Ball; arguably it should be Dreamers’ Ball) is in truth one of his weaker efforts, a poor relation of the magnificent big-band sound of Good Company. The rather ponderous feel is perhaps deliberate, evoking (for this listener at least) a sleazy late-night bar, complete with cast-off, booze-soaked dreamer drowning his sorrows.

The acoustic early-take released in 2011 is also somewhat leaden, though the finished version features nice multi-tracked lead guitar and backing vocals. Best moment: the guitars from 2:48 to 3:10.

159. Friends Will Be Friends (Deacon/Mercury), A Kind of Magic, 1986

This song perhaps tries a little too hard to capture the anthemic, arms-in-the-air quality of Queen’s best stadium-ready songs (the video is a big clue to its intent — the nearest Freddie ever got to crowdsurfing, despite what a certain well-known film might suggest to the contrary).

Released as a single to coincide with the Magic Tour, it was inexplicably placed between We Will Rock You and We Are the Champions at the climax of the show — an egregious error, as far as this fan is concerned. As often, the guitar breaks (particularly at roughly 1:58 and in the outro at 3:44) are the best bits.

158. It’s a Beautiful Day (Reprise) (Queen), Made in Heaven, 1995

157. It’s a Beautiful Day (Queen), Made in Heaven, 1995

Apparently, a half-idea of Freddie’s from the Game sessions (a bit like what became the opening bit to Breakthru), it’s such a shame he didn’t pursue it further. A wonderfully optimistic lyric, less decadent and hedonistic than Don’t Stop Me Now. Nicely moulded into a coherent shape by the band, including samples of early songs on the reprise.

156. Coming Soon (Taylor), The Game, 1980

After his two funky missteps on the Jazz album, this is more typical Roger fare. Propelled along by a driving drum beat, I Wanna Testify-type vocal flourishes and what sounds like Roger on rhythm guitar, this doesn’t quite hit the heights, though the backing vocals at 1:35 and at the end are gorgeous. A Human Body would perhaps have been a better choice of second Roger song on The Game, with this as the non-album b-side.

155. Tear It Up (May), The Works, 1984

A sledgehammer of a song from Brian that lacks the subtle shades of his very best heavy songs: a tribute to wild partying but without the wit of Freddie’s Don’t Stop Me Now. It’s certainly a statement of intent lyrically and musically: we’re here to have a good time, we’re here to rock. It draws a line under Hot Space, as if to say ‘we know we pissed off a lot of our fans with the dance stuff’. Indeed, that sentiment was in part the inspiration for the album’s title — ‘we’re going to give ’em the works’. Full-on, driving guitar compensates for awful, crashing drums.

Despite the lyrical theme, it was an unlikely set opener on the Works tour. Even more surprising that it remained in the set for the Magic Tour. Even more surprising that it was resurrected by Q+AL.

154. Let Me in Your Heart Again (May), released 2014

Another promising but unfinished idea (again, one wonders why), this one from the Works sessions and nicely shaped into something releasable by Brian and Roger. Fred Mandel plays keyboards — check out his comments on the song in this interview at roughly 45:15. The Anita Dobson version is worth a listen for Brian’s guitars, though perhaps not for the singing.

153. A Dozen Red Roses for My Darling (Taylor), b-side, 1986

An example of where that ’80s Phil Collins-esque, big-yet-compressed, dry drum sound works well (taking the lead in this instrumental), this is a delightfully left-field Roger creation. The repeated guitar riff is great, as are the synths. It was reworked into a more traditional song for the A Kind of Magic album, but A Dozen Red Roses definitely works as a piece of music in its own right.

Best moment: the atmospheric break at roughly 2:09, which sounds like a cross between something from side two of David Bowie’s Low album and the X-Files theme.

152. The Loser in the End (Taylor), Queen II, 1974

Perched at the end of side one on the original vinyl release, Loser in the End follows uneasily — both lyrically and musically — in the wake of Brian’s magnificently dark and introspective suite of songs, the juxtaposition as jarring as the guitar flourishes in the song itself. The theme is typically early-years Roger, the inter-generational tensions involved in growing up and embracing rock-‘n’-roll, girls and fast cars.

Best moment: Roger’s percussion, particularly the repeated marimba sounds (for example at 0:06).

151. Feelings, Feelings (May), released 2011

From the News of the World sessions, this song didn’t make it through the weeding process to the final album cut, and at roughly two minutes’ duration it obviously remained unfinished and unpolished. Its upbeat, rocky feel is reminiscent of It’s Late and the latter part of the BBC session version of Spread Your Wings from the same period.

150. The Invisible Man (Queen), The Miracle, 1989

One of Queen’s more ‘humorous’ pieces, it certainly has an infectious bassline and nice guitar from Brian — though, take away the various aural flourishes and it’s not immediately obvious what else the track offers. Many people will doubtless disagree but it’s also one of their less likeable ‘thematic’ videos: as with anything using technology as a central reference (in this case, video games), it quickly dates.

It is widely reported that the Miracle album was originally going to be called The Invisible Men. Someone, somewhere — fortunately — had a change of heart.

149. Sleeping on the Sidewalk (May), News of the World, 1977

In a sign of things to come, much of this blues-y piece was apparently recorded in a single take. Like many of Brian’s lyrics, he is wrestling with the price of fame and success, though with more humour that is typical in his songs. The live version from the News of the World tour, released in 2017 with Freddie on vocal, was an unexpected delight on its release: one wonders where it was placed in the set during its (very) limited run.

Best moment: leaving the laugh in at the every end of the take (very much not a Queen thing up to that point).

148. One Year of Love (Deacon), A Kind of Magic, 1986

Another of Freddie’s more ‘shouty’ vocals from the ’80s, One Year comes complete with saxophone solo and orchestral arrangement. It is by no means the worst of the ‘mushy ballad’ type but, with its plodding beat, struggles to go anywhere particularly interesting and is sorely missing Brian’s guitar.

147. Crash Dive on Mingo City (May), Flash Gordon, 1980

It may only last a minute or so but Brian’s guitar, joined by Roger on timpani, evokes Flash’s frantic crash-dive through the city’s defence shield, ruining the wedding and mercilessly killing Ming in the process.

146. The Hitman (Queen), Innuendo, 1991

This certainly sounds like a no-holds-barred Brian rocker, though there is a lengthy quote ‘out there’ attributed to Brian, saying that the original idea came from Freddie with further work from John. It is full-on and relentless, leaving little room for subtlety, though it has some outstanding guitar from Brian.

145. Funny How Love Is (Mercury), Queen II, 1974

The weakest of Freddie’s songs on Queen II, Funny is notable for the Phil Spector-esque ‘wall of sound’ arrangement, courtesy of Robin Cable’s production (also featured on Freddie’s Larry Lurex arrangement of I Can Hear Music). A somewhat slight song, although it comes in at nearly three minutes the fade-out starts ridiculously early.

144. Man on the Prowl (Mercury), The Works, 1984

A more full-on, Elvis-inspired, rockabilly arrangement than Crazy Little Thing Called Love, this is upbeat throughout, and has a great middle-eight (“Well I keep dreaming about my baby …”) and piano solo to finish, courtesy of Fred Mandel, who had played keyboards on stage with the band in 1982. Apparently it was pencilled in as a single (another?!) from The Works until Thank God It’s Christmas came along.

143. Hang On In There (Queen), b-side, 1989

This track didn’t make the Miracle album but is undoubtedly better than some that did. It sounds like a number of studio jams spliced onto a basic song, notably at roughly 2:30 and 3:10 (the latter Brian-John-Roger jam is particularly good, using part of what was widely known in bootleg circles as Fiddly Jam).

142. Life Is Real (Song for Lennon) (Mercury), Hot Space, 1982

Life Is Real has a somewhat uncharacteristically serious ‘price-of-fame’ lyrical theme from ’80s Freddie. Always a big John Lennon fan, he was obviously devastated by the Beatle’s untimely death in December 1980. However. the song is rather pedestrian and doesn’t quite do justice to the undoubtedly heartfelt sentiments. Like (say) The Invisible Man, strip away the flourishes and what is left is something rather ordinary by Queen standards that would probably not have made the cut on any of the first six albums.

Peter Freestone, Freddie’s longtime personal assistant, later wrote that an early version of what became the opening line “Guilt stains on my pillow” began as “Cunt stains…”. The lyrics – apparently pieced together from a brainstorming of random lines (the same process was used with I’m Going Slightly Mad) – are probably the strongest element of the track.

Best moment: the powerful “Life is real…” mini chorus at roughly 1:38.

141. Dear Friends (May), Sheer Heart Attack, 1974

At just one minute and nine seconds, this is an affecting piano ballad in miniature. One cannot help but feel that, by the ’80s, an idea such as this would have been worked on to bring it closer to a more conventional three-minute length or abandoned. Best moment: the backing vocals from 0:32.

More about Queen

Queen Songs Ranked 185–161

Intrigued and inspired by a blog I came across on Twitter in late-October 2018 — annoyingly, I can’t find the link, but there are plenty like it — I began drawing up a complete list of Queen songs, ranked from ‘worst’ to ‘best’.

Obviously this is all completely subjective, and I don’t doubt that my views will change as I go along. If nothing else, it’s great fun to do and a perfect excuse to listen to and appreciate (to a greater or lesser extent) every single Queen song, not least the ones I usually unthinkingly dismiss and rarely play. I don’t really have a musical vocabulary, but I will try and explain my thinking as best I can. Any time references relate to versions I found on the official Queen channel on YouTube, unless stated otherwise.

First, a few words about what’s in and what’s not. I fully accept that this is a bit arbitrary, though there is a logic of sorts.

- It encompasses every Queen studio song released either on an album or as a b-side up to Freddie’s death — so Mad the Swine makes the cut, for example.

- I decided to include God Save the Queen and The Wedding March, even though they are arrangements of traditional pieces of music, because they are very obviously ‘Queen-ified’.

- On reflection, I decided to include the Made in Heaven album because Freddie was involved in at least some of the recording process. Based on that criterion, I have also included Feelings, Feelings and the three tracks that featured on the Queen Forever compilation. I have not, however, included No One But You, which had no Freddie involvement.

- There are no live tracks or session tracks — including no ‘fast’ version of We Will Rock You. Boo.

- To keep things simple, I am counting reprises as separate tracks, except Seven Seas of Rhye from the first album (which, strictly speaking, is a taster rather than a reprise anyway!).

- Other than the reprises, which all stand as separate tracks on albums, there are no officially released early takes, remixes or reworkings included — so no Forever (boo … again), for example, and (mercifully) no Blurred Vision, which would otherwise have been propping up the entire Queen oeuvre.

- I decided against the so-called ‘Track 13’, classing it as a piece of ambient music rather than a song as such. It isn’t, for example, listed on the Made in Heaven album cover.

- I compiled this list in late 2018 so it doesn’t include any of the previously unreleased tracks that came out as part of the Miracle box set in 2022. Click here for my thoughts on the box set as a whole.

This selection — from 185 to the dizzy heights of 161 — contains mainly b-sides, plus incidental and dialogue-heavy pieces from the Flash Gordon soundtrack. There are also a number of songs from the Miracle sessions. Two singles (both minor hits) also feature — not my favourites, obviously.

185. Chinese Torture (Queen), The Miracle bonus track, 1989

A Brian experimental ‘thing’ that echoes bits of his ’86 Magic Tour solo (but it’s definitely no Brighton Rock!).

184. Stealin (Queen), b-side, 1989

From the Miracle sessions, this has obviously taken shape from a jamming session. A quintessential ‘minor’ b-side song.

183. Lost Opportunity (Queen), b-side, 1991

From the Innuendo sessions, it’s a blues piece that would have been suited to Brian’s first solo album (indeed it has the same feel as Nothing But Blue).

182. Don’t Try Suicide (Mercury), The Game, 1980

My least favourite Queen album track. As an attempt at black humour, it comes up short (“… You’re just gonna’ hate it … Nobody gives a damn”). The brief uptempo bits (“You need help …” and the guitar solo) rescue it from being completely awful. It would have been far better as an exclusive b-side release with A Human Body taking its place on The Game.

181. The Ring (Hypnotic Seduction of Dale) (Mercury), Flash Gordon, 1980

180. Arboria (Planet of the Tree Men) (Deacon), Flash Gordon, 1980

179. Ming’s Theme (In the Court of Ming the Merciless) (Mercury), Flash Gordon, 1980

Essentially mood music. Ming’s Theme contains some fairly menacing synthesizer.

178. Flash’s Theme Reprise (Victory Celebrations) (May), Flash Gordon, 1980

177. Marriage of Dale and Ming (And Flash Approaching) (May), Flash Gordon, 1980

176. Flash to the Rescue (May), Flash Gordon, 1980

Essentially narrative interludes, helping the story along. Marriage of Dale and Ming includes some nice guitar on the Flash snippets. Flash to the Rescue carries a sense of heightening drama, as if setting up the action to come. In an interview celebrating the fortieth-anniversary re-release of Flash Gordon, Brian highlighted Flash to the Rescue as one of his favourite bits of music from the film [from roughly 8:55].

175. Body Language (Mercury), Hot Space, 1882

By some distance Queen’s worst choice of single — and a lead-off single at that. Either Staying Power or Back Chat would have been a much better choice. Body Language was omitted from both Greatest Hits II and Greatest Hits III. By all accounts, this was more or less an exclusively Freddie creation in the studio. Typical of his more aggressive, ‘shouty’ style of singing in the ’80s. There is little or no Brian guitar.

Here’s a bit of telling trivia: it is the only lead-off single from an album that wasn’t given a regular slot in the live set at time of release. (It was played just twice on the Hot Space European tour.) When played live on the US and Japan legs of the tour, it was considerably rockier and (therefore) much improved. This won’t be the last time I say those words.

174. Execution of Flash (Deacon), Flash Gordon, 1980

Short and simple — but effective: a few basic notes on guitar (presumably played by John) combining well with a suitably funereal orchestral sound.

173. Hijack My Heart (Queen), b-side, 1989

Another song from the Miracle sessions. With Roger on vocals, this sounds like it could have featured on Shove It! — the first Cross album (but really a Roger solo album). The guitar riff is very Roger.

172. There Must Be More to Life Than This (Mercury), released 2014

Originally part of the Hot Space sessions, this version includes nice guitars and is superior to the version on Mr Bad Guy, but it suffers badly from a weak Michael Jackson vocal performance when set alongside Freddie’s voice.

171. Thank God It’s Christmas (May/Taylor), 1984

The fact that this Christmas song only reached Number 21 in the UK charts speaks volumes. It is middle-of-the-road and unadventurous fare with equally bland lyrics, and lacks any kind of genuine festive spirit (perhaps because it was recorded in the summer). The best thing about it is John’s driving bass.

170. The Wedding March (Arr. May), Flash Gordon, 1980

May’s short ‘Queen-ified’ arrangement of Wagner’s Bridal Chorus from Lohengrin, with a suitably brooding ending (Dale is after all being forced to marry the dastardly Ming).

169. My Baby Does Me (Queen), The Miracle, 1989

Typical of the funky, laid-back feel that Freddie and John were fond of creating in the ’80s, the problem is that it doesn’t really go anywhere, and is seriously marred by vacuous lyrics and a soulless drum-machine backing.

168. More of That Jazz (Taylor), Jazz, 1978

Their weakest album closer, More of That Jazz sits neglected and unloved in the musical and lyrical shadow cast by the exuberant Don’t Stop Me Now, which precedes it. Sounding very much like one of Roger’s more-or-less solo efforts, it is hampered by uninspired lyrics — ‘Give me no more of that jazz’ just does not work as the closing message of an album called Jazz — and further weakened by the unnecessary inclusion of a hideous mashup of earlier tracks. They did the same thing with the 12″ remix of I Want to Break Free. An awful decision.

167. Party (Queen), The Miracle, 1989

The weakest (by far) of Queen’s album lead-off songs, this is based around a heavy, programmed drum beat. It’s rescued by some zippy guitar work from Brian. It is well worth searching out the original version (with real drums) that came out as part of the Miracle box set in 2022. As I write here, at what point in the process did someone (who?!) suggest replacing the drums with programmed drums?

166. Rain Must Fall (Queen), The Miracle, 1989

Another of the weaker Miracle tracks with a synthesized drum beat far too prominent in the mix. Freddie’s repeated use of “cool” dates the song. However, the basic track is considerably enhanced by Roger’s percussion, a scintillating guitar solo from Brian and some great bass from John, especially from roughly 3:10 onwards.

165. Fun It (Taylor), Jazz, 1978

Roger’s first experiment in funk in which he and Freddie share lead vocal duties. It includes several trademark Roger frills, but ultimately sounds like a demo. Like many of the songs on Jazz, it would surely have worked better with more inspired production. A foretaste of the cold ’80s drum sound to come.

164. God Save the Queen (Arr. May), A Night at the Opera, 1975

Originally recorded in 1974 to close the live show, Brian’s arrangement served two important functions: it was an inspired choice to close Queen’s Sgt Pepper and it was surely the only thing that could have followed Bohemian Rhapsody.

163. In the Death Cell (Love Theme Reprise) (Taylor), Flash Gordon, 1980

162. Escape from the Swamp (Taylor), Flash Gordon, 1980

161. In the Space Capsule (The Love Theme) (Taylor), Flash Gordon, 1980

Three great mood pieces from Roger, combining timpani and synthesizer to great effect. There’s a haunting, ethereal quality to the synth sound, reminiscent of his excellent Fun in Space solo track (which was presumably being worked on at roughly the same time).

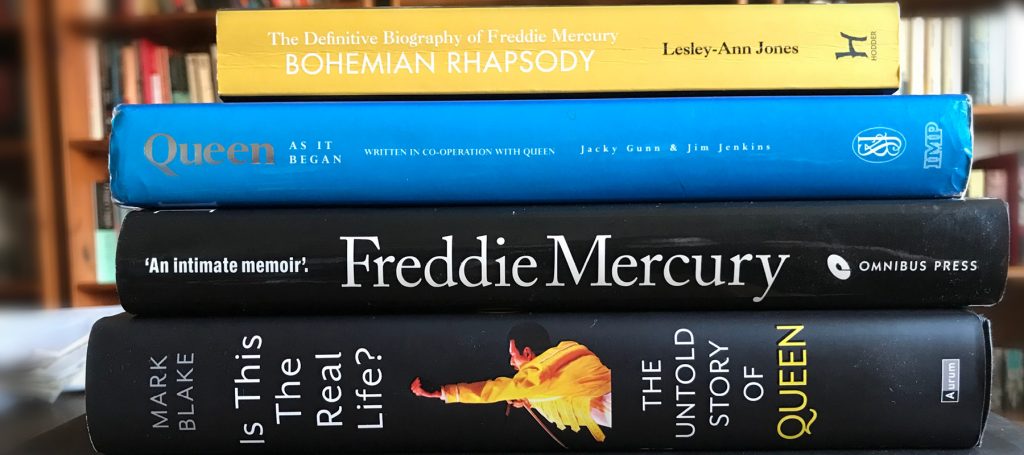

Bohemian Rhapsody Film Review

Having now seen Bohemian Rhapsody for a second time, here’s an attempt to bring some order to a mad jumble of thoughts — what works and what doesn’t, whether the inaccuracies matter, whether it is fist-pumpingly brilliant or wince-inducingly awful, whether it is respectful of the Queen legacy, and above all whether it is a worthy addition to the Queen canon.

On the whole, I like the film. That was never a given. I am sure that nobody seriously expected a groundbreaking, genre-redefining, Oscar-sweeping piece of art — like the song Bohemian Rhapsody itself, say — but on the quality spectrum I was crossing my fingers for something more akin to The Doors than Spiceworld: The Movie. It’s short-sighted to wax lyrical about every last Queen product — this replica sixpence, that T-shirt, this vodka, that board game. Some things are high quality and worthwhile; others are mediocre and a bit naff. There Must Be More to Life Than This (the Queen & Michael Jackson version) is ordinary at best. I never particularly got into Roger’s band The Cross. I have not seen — nor do I intend doing — the We Will Rock You musical. Objectivity matters, even where ‘classic’ Queen is concerned and even more so in the case of post-Freddie and non-Queen projects.

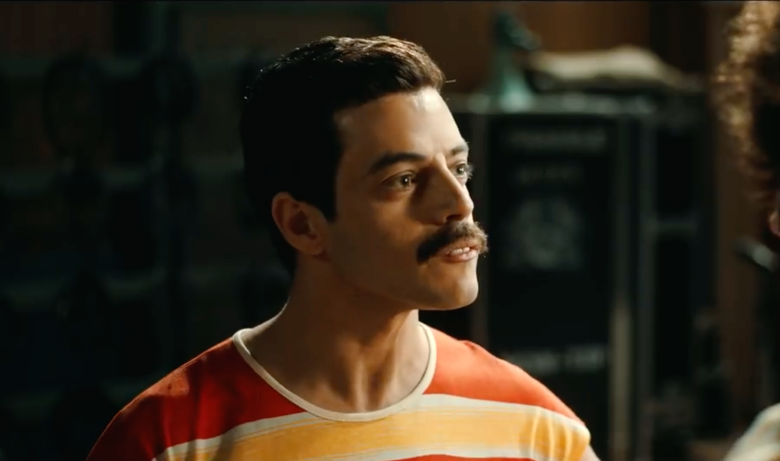

With regards to the film, I hadn’t paid too much attention to the various high-profile squabbles and sackings over the years. But with the publication last year of a series of appetite-whetting stills, followed by the drip-drip release of various trailers, and finally the recent publicity and hype, I was aware of an established consensus of sorts among fans before the film’s actual release: the four central acting performances (particularly Rami Malek) are amazing, it was said; the concert scenes are great; the attention to ‘authenticity’ is astonishing, though they take liberties with the ‘real’ story; plus a vaguer sense that it is going to be a rock ‘n’ roll rollercoaster ride, propelled along by an irresistible soundtrack.

Well, yes and no.

The soundtrack album was the first surprise. To be honest, I had expected Queen Productions Ltd to churn out another rehashed ‘greatest hits’ package. What emerged was a well-above-par release, with little nuggets of gold dotted throughout — from the previously unreleased guitar-rich version of Don’t Stop Me Now and the Queen-ified ‘Fox’ fanfare to the delightfully re-recorded Doing All Right and (best of all) the raw, thumping live Fat Bottomed Girls from Paris in 1979 — not even the version from the widely circulated bootleg video. Definitely promising.

The second ‘surprise’ — if surprise it is — was how many of the rumours were just plain wrong, yet another reminder to consume media tittle-tattle with a large helping of scepticism. Some at least of Sacha Baron Cohen’s version of history appears to be nonsense, though the script (if indeed there even was a script at that stage) will have undergone a million re-writes since his time. Among other canards, Brian’s first wife Chrissy does indeed appear in the film, as do all the ‘wives’ (for use of inverted commas, see below), and the accusations of ‘hetero-washing’ (ignoring or downplaying Freddie’s homosexuality) are way wide of the mark — indeed, scenes of men kissing men probably outnumber those of heterosexual canoodling.

The main weakness of the film for me is the balance of the script, a symptom of the lack of clarity about what sort of film this is trying to be. I wrote months ago on a fan forum that it was:

…far more important [for me] for the film to portray the power and impact of Queen’s live show.

In my mind, this was to be a film about Queen. But Bohemian Rhapsody purports to be a ‘biopic’ — a biographical film of Freddie’s life, focusing on the years from 1970 to 1985. In truth, it is a messy hybrid of the two. In part, it is a tongue-in-cheek whistle-stop re-enactment of key moments in the band’s history. Especially with the active involvement of Brian and Roger in the film’s production, Bohemian Rhapsody feels at times like a vehicle for (some of) the band’s greatest hits — a visual jukebox — and will doubtless be enjoyed by many for this very reason.

Bohemian Rhapsody is also an attempt at a deeper study of Freddie — flamboyant free spirit, creative genius, tortured soul. The film’s opening scenes take time to establish him as an awkward, restless outsider (a regular target for casual racism, for example), stumbling to realise vague dreams of stardom. Far from a fast-paced rollercoaster ride, I suspect that some will find these elements of the film ‘slow’. Above all, there are several scenes exploring the relationship between Freddie and Mary, the pivot around which the whole film revolves. Lucy Boynton as Mary is excellent throughout: the moment when she pretends to take a drink at Freddie’s insistence during a late-night phone call, thus signalling a release of sorts from his spell, is particularly affecting.

Comments by the historian Anthony Beevor, who wrote recently about war films, are interesting and relevant in relation to the film:

The real problem is that the needs of history and the needs of the movie industry are fundamentally incompatible. Hollywood has to simplify everything according to set formulae. Its films have to have heroes and, of course, baddies – moral equivocation is too complex. Feature films also have to have a whole range of staple ingredients if they are to make it through the financing, production and studio system to the box office. One element is the “arc of character”, in which the leading actors have to go through a form of moral metamorphosis as a result of the experiences they undergo. Endings have to be upbeat…

Ironically, the basic Freddie story does loosely conform to this by-the-numbers story arc: meteoric rise followed by downfall, before redemption (here during a Munich rainstorm — the pouring rain a familiar trope, symbolising cleansing and re-birth) and the grand Live Aid finale. However, the script is unable to handle the sheer quantity of source material, resulting in ridiculously contrived situations and jaw-dropping narrative leaps. Thus, Freddie meets the band and (separately) Mary at the same Smile gig — the exact same night that Tim quits to join Humpy Bong. Elsewhere, Freddie and John debut with the band on stage at the same time — the night, coincidentally, of the broken microphone stand. Most ridiculous of all (as Alexis Petrides points out in The Guardian), Freddie turns up unannounced on Jim Hutton’s doorstep to declare his love, and then reconciles with his (Freddie’s) father over tea and cakes — all on the same morning — before nipping across to Wembley Stadium to steal the show at Live Aid. A busy day indeed.

This brings us more generally to the thorny issue of historical accuracy and fidelity to the facts. Broadly speaking, events in the film fall into one of two periods of Queen history — ‘early’ and ‘late’. Within — and even across — these periods, the chronology is alarmingly fluid, and, as we were pre-warned, whole chunks of the Queen story are ignored, glossed over or turned upside down. A camper van, used for gigging up and down the country, is sold on Freddie’s initiative to pay for studio time: in reality, of course, Queen did almost the opposite, refusing to tread the usual ‘pub and club’ circuit — actually one of the things that immediately set them apart from run-of-the-mill bands at the time. John Reid arrives on the scene a couple of years early (around the time of the first album) and leaves about six years late (at the time Freddie was offered a solo deal by CBS): in reality he was the band’s manager for just three years. Rock in Rio acts as a backdrop for Freddie’s break-up with Mary — events probably eight years apart in reality. Before Live Aid, Roger exclaims that the band haven’t played live for years — helping to set up the dramatic finale but, of course, a fiction: the Works tour came to an end in Japan just two months before Live Aid.

Some of the inaccuracies are more puzzling, seemingly unimportant to the storyline. Freddie is shown smoking in ’75, several years before he actually started. Dominique Beyrand, Roger’s then girlfriend, is referred to as his wife (they only married in 1988). Journalists raise the spectre of AIDS at a press conference for the release of the Hot Space album, which would have been in 1982, a year before scientists had even formally identified the virus. Jim Hutton is working as a waiter at one of Freddie’s house parties when the two first meet; they actually met in a nightclub. And photo evidence may provide evidence to the contrary, but some of the costumes just don’t ring true — Brian’s orange Adidas top in the We Will Rock You scene, to name one. Trivial though these details are, they nevertheless sit uncomfortably alongside Queen official archivist Greg Brooks’ unwise assertion that “… the Fox team were obsessed with detail; getting every aspect of every scene perfectly right”. No, Greg; they obviously weren’t.

Two figures loom large in the background. The role of arch-villain, as had been well trailed, is assigned to Paul Prenter, the eminence grise, fuelling Freddie’s hedonistic lifestyle and — motivated by infatuation and greed — increasingly blocking all contact between Freddie and the Queen ‘family’, and between Freddie and Mary. Prenter’s real part in the Queen story is well known, but I have sympathy (again) with the critic Alexis Petrides, who argues that the demonisation of Prenter necessitates portraying the rest of the band as conventional, clean-living, sober chaps. Perhaps this is the reason why Dominique Beyrand is referred to as Roger’s wife — a clumsy attempt to juxtapose the band’s growing maturity and sense of responsibility with Freddie’s wild abandon (early scenes make clear the younger Roger’s fondness for partying). We see no wild Queen parties and there is no collective band meltdown in Munich, both of which are perhaps closer to the truth than what we see in the film.

Less expected was the portrayal of Jim Beach. In contrast to Prenter, he is a sober, steadying influence. Jim is an almost ubiquitous presence — during tricky negotiations with the record company, during a critical band reconciliation scene in his office, even during recording sessions, dutifully completing paperwork at a side-table. He is there in the background at band rehearsals for Live Aid when Freddie reveals his HIV status to the band (the implication being, of course, that Jim already knew). In a Jeeves-ish final twist, it is Jim who increases the volume on the mixing desk at Live Aid before Queen’s set — in reality, it was a sound guy called Trip Khalaf.

The on-stage scenes are good, though it would be going too far to say that they faithfully ‘copy’ Queen live. The lengthy Live Aid sequence is an exception; it is carefully recreated. The use of ‘live’ recordings works extremely well, and the actors’ miming is good, particularly Malek’s lip-synching. Again, some aspects of the live scenes are just fabrications: for example, each member of the band — even John! — is shown introducing themselves to the audience as Freddie holds his microphone horizontally. We already knew before the film came out about the placing of Fat Bottomed Girls early in their career: it is used to soundtrack a blistering first tour of the States, years before its actual release.

Some inaccuracies are no big deal — the lighting rig a cross between the ‘pizza oven’ and the ‘G2 razors’, Freddie throwing his leather jacket across the stage towards the crowd, dry ice during We Will Rock You. We knew about the crowdsurfing from the trailers, of course. How I wished this had found its way to the cutting-room floor. Alas, no. Jim Morrison used to jump into the crowd. Maybe for him it was spiritual, his way of connecting with the audience. Freddie was a showman and entertainer, glorying in his superstar persona, urging us in the midst of ‘70s recession and industrial decline to drink champagne for breakfast. He was not a crowdsurfer.

And what of the band performances? Rami Malek is indeed excellent. The ‘biopic’ format does not best serve Gwilym Lee, Ben Hardy and Joseph Mazzello, over-accentuating as it does Freddie’s role and importance, leaving their characters somewhat underdeveloped. I also struggled at first to reconcile what I saw on the screen with my own perceptions and preconceptions of my childhood heroes. Only on second viewing did I really warm to their performances. Gwilym Lee certainly captures Brian’s voice and mannerisms. The younger ‘Brian’, however, felt too carefree and jokey: I find it difficult to imagine Brian engaging in witty repartee. ‘My’ Brian is the epitome of solemnity — serious, studious and deeply thoughtful.

Mazzello brings out John’s quiet steadiness, though his facial expressions veer uncomfortably close towards gurning at times, and his on-stage ‘Deacy’ moves are a little over-exaggerated. Well done to Ben Hardy for nailing the Hammer to Fall drum parts. However, other than for his ‘Galileos’, non-Queen fans may wonder at Roger’s importance in the band. Of the four, his part seemed the most obviously underdeveloped, though he was involved with Freddie’s younger sister in the film’s funniest exchange:

ROGER: So Kash, what are you doing later?

KASHMIRA: Homework.