Henry VI and the Wars of the Roses

The past, it is proverbially said, is a foreign country. Perhaps it is, though in my case huge chunks of English history – the whole of the medieval and early modern periods, for example – were for a long time more like a far-off world than merely a place somewhere beyond the shores of Britain. As I admitted in my blog Enlightenment Now: Book Review, I plead guilty to half a lifetime of appalling narrow-mindedness. I have always thought of myself as a historian, but my focus for far too long was shockingly circumscribed – restricted to modern and contemporary history, and in fact nothing much beyond post-1900 high politics in Britain and Europe, war and international relations, and political ideologies.

That meant yes to the Russian Revolution and no to the agricultural revolution. Political diaries and memoirs were definitely in; medieval manorial rolls and church records were just as definitely out. I was up for a visit to the library to read copies of the New Statesman from August 1914 but not to a ruined castle to smell the history that surrounded me. I still recall the gentle rebuke from the head of the university’s history department when I requested a special dispensation to change the topic of my undergraduate dissertation: a proper historian doesn’t want to pick and choose, the professor (rightly) chided me.

Perhaps it came from our history diet at school, as hit and miss as the school meals they served us. As a kid, I wasn’t interested in either royalty or religion, but the vast bulk of what we were taught in class seemed to involve matters dynastic or religious. (I can’t remember ever studying anything post-Tudors until I was in sixth form, though we surely must have at least done the Industrial Revolution at some point.) Even simple family trees baffle me to this day, so it’s no great surprise that the tangled webs of family lineages, the rival dynastic claims and the flux of ever-shifting loyalties, so central to many of the narrative threads of the Middle Ages, left me cold.

Once I started to take studying seriously, I realised that I found history one of the easier subjects and I liked my teacher. O levels rewarded factual recall above everything: if memory serves, the history exam involved little more than regurgitating five pre-learned essays in two and a half hours. I had memorised whole extracts of Virgil’s Aeneid for the Latin exam so, yes, that was no problem. But was I properly engaging with the content? Did I fully understand what I was writing? Almost certainly not.

Times and tastes change – however slowly in my case. Ian Kershaw’s To Hell and Back, the first of his two-volume history of the twentieth century, sits on my bookshelf, as yet unread. I would have instantly devoured it a decade ago. Two more favourite historians of mine, Richard Overy and Anthony Beevor, both have major books out that in times gone by I would have picked up on day of release. I don’t as yet have either.

My favourite history read of the last year was probably Tom Holland’s Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind. It is the type of history I most look forward to reading nowadays. Holland is one of a group of historians — Dan Jones and Marc Morris are two others who immediately spring to mind — who regularly publish huge and hugely enjoyable histories that mix an engaging and accessible narrative writing style with excellent factual detail and knowledge of current research. Their work has done much to draw me to pre-modern history and to illuminate its highways and byways. And so too has historical fiction – though the exceptional books of the likes of Hilary Mantel, Kate Mosse and SJ Parris are well worth a blog of their own.

And so we come to the fifteenth century, a century that I have always steered well clear of (the Wars of the Roses in particular, another hangover from school days, I suspect). For anyone whose knowledge of the period is as sketchy as mine, I suppose the key point to grasp is the significance of the removal from the English throne – and subsequent murder – of Richard II, the last of the Plantagenets, in 1399. The usurper was Henry IV, the first of the Lancastrian kings.

The great upheavals of the following century ultimately come back to the question of legitimacy – the right to rule – ending not a little ironically with the rise to power of the Tudor dynasty whose claim to the throne was, in Dan Jones’ words, “somewhere between highly tenuous and non-existent”. Such a poor claim might go unchallenged in the event of strong and decisive leadership, but a monarch who appeared unfit for the role – indecisive, say, or militarily incompetent – would be in serious trouble. This was to be the fate of Henry VI.

Henry IV’s reign was plagued by rebellions and further destabilised by recurring illness. His son Henry V’s reign was highly successful in medieval terms – his reputation as an accomplished and personally courageous warrior-king immortalised by victory against the French at Agincourt in 1415 – but it was also disastrously (for the House of Lancaster) short: he died suddenly in 1422, leaving his son to become Henry VI at the age of just nine months.

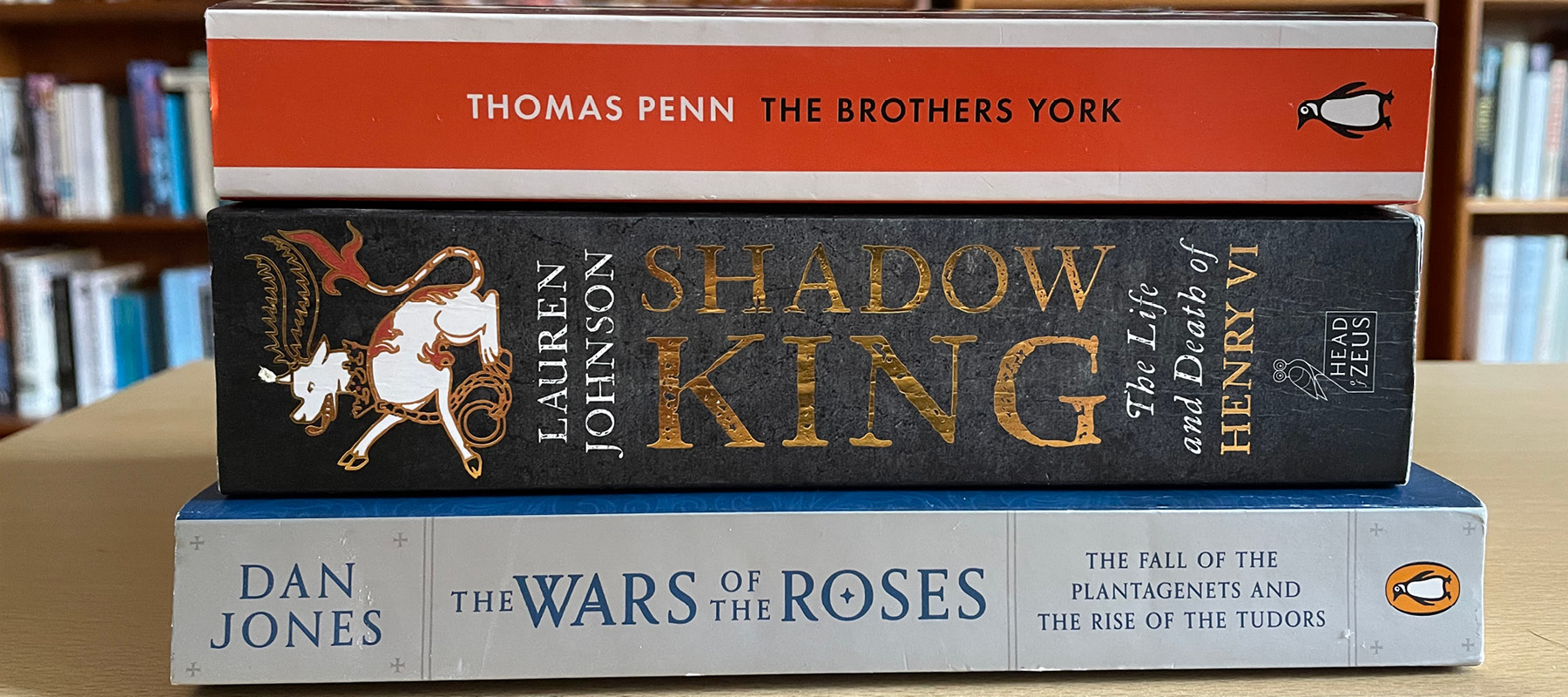

A year or so ago I read a 2019 biography called Shadow King: The Life and Death of Henry VI by Lauren Johnson. It is well written and (importantly for me) user-friendly for the non-specialist. Johnson offers frequent reminders of who people are, their titles, former titles, familial connections etc, as well as a comprehensive Who’s Who as an appendix. The writing has an engaging narrative drive to it, with chapters typically ending on a cliffhanger.

My first impressions of Henry were of how unorthodox he was. As a king utterly out of step with the medieval view of monarchy, he seems to have had much more in common with Richard II (both Henry and Richard suffered the same fate, being deposed and murdered) than with his father, Henry V. In an age when ‘rules’ and codes of behaviour were all-important, it is no surprise that his actions (and inactions) caused such discombobulation.

Reading about the younger Henry’s unwillingness to follow the accepted rules put me in mind of President Woodrow Wilson and his doomed attempts to remake the international order at the end of the First World War by ditching the old system of power politics and alliances in favour of collective security and a League of Nations. There is also a parallel of sorts with President Trump, a blundering amateur who disregarded almost all foreign policy norms and conventions, believing that he could do personal deals that would solve age-old problems and end age-old rivalries. In reality, his meddling did more to stoke than to solve conflict.

Henry also resembled Richard II in displaying a fatal incompetence at crucial moments. For all that Henry’s mindset might not be out of place in the modern world, it was simply unacceptable in a medieval monarch. A man of honourable intentions, he was undermined by indecisiveness and an unwillingness to be sufficiently ruthless at key moments of his reign. He was deeply pious and equally deeply naïve. Time and again, for example, he chose to accept the solemn oaths and declarations of loyalty served up by his rivals, only to be later betrayed.

And despite being schooled in kingship from a young age, he came to depend on others, to the point that whoever controlled him controlled the kingdom — a recipe for calamity. Again, there is a parallel with the disastrous presidency of Trump: what to do when the top person is simply not up to the job. Henry VI was not just a poor decision-maker, he also suffered serious bouts of mental illness.

One thing I don’t particularly like about works of ‘popular history’ – notwithstanding the point above about narrative drive – is their tendency to stray worryingly close to ‘historical fiction’ territory. Well-researched novels that are set in the past complement history writing, but novel writing is a separate craft and the distinction between the two should not be blurred.

Take this, just one example from many in Johnson’s book, describing the loading of a ship with treasure at the port of Sandwich in 1432:

In the darkness of the harbour mouth, lights flashed and glared. Above the low creak of ships’ timbers, men’s voices punctured the frosty stillness of the night. Occasionally there came a low thump of coffers hitting the decking. A groan. A cricked back. And then the great chests lifted again, edged closer, step by heavy step, towards the tilting flank of a ship called Mary of Winchelsea.

Lauren Johnson, Shadow King: The Life and Death of Henry VI, from chapter 7

My first thought on reading that: how does the author know about the creaks and the groans and the low thumps, other than through guesswork? The footnote attached to the paragraph as a whole refers to a biography of Cardinal Beaufort (whose treasure it was) by GL Harriss and presumably relates to a fact Johnson gives us about the value of the cargo, Beaufort’s entire wealth.

And this is the opening sentence of Part IV of Dan Jones’ book on fifteenth century England:

The fourteen-year-old boy traveled through south Wales alongside his forty-year-old uncle and a band of loyal retainers, making their way toward unstable country, thick with woods and pocked with the turrets of glowering castles.

The rest of the page continues to refer to ‘the boy’ and ‘the man’. It is not until the following page that Henry Tudor and his uncle, Jasper, are identified by name. All very atmospheric but more the sort of thing I might expect to read in a work of fiction.

That apart (and I have no doubt many readers love such writing), Jones is an excellent guide through the maze of late-fifteenth century dynastic politics. His earlier book The Plantagenets (published in 2012) was an outstanding introduction to medieval English history and is high up my list of books to reread. I did not, however, find The Wars of the Roses as agreeable a read. The title itself is somewhat misleading, in my opinion. It turns out to be for the US edition – should Amazon (from whom I bought the book) make this more obvious? I was a bit miffed when I realised – hence spellings like ‘traveled’, ‘laborer’ and ‘ax’. In the UK the book was published as The Hollow Crown.

The events of the years 1461 to 1483 – the ‘dates’ of the Wars of the Roses that I memorised as a child – form only one section of the book, which opens in the 1420s and so covers much the same ground as the Lauren Johnson biography of Henry VI. It is this first half of the book – the period up to the deposition of Henry in 1461 – that is the better half. The rest by contrast, feels somewhat cursory. The reign of Edward IV is dealt with relatively briefly, especially the years after 1471 when he returned to the throne after the short second reign and then death of Henry VI.

Similarly, the author attempts to cover the rise of the Tudors and the consolidation of their power under Henry VIII in under a hundred pages. To be fair, Jones’ focus is very much on the attempt by the new dynasty to establish their version of history in the popular imagination – a story that ends in a united realm under the Tudor rose, naturally.

Next up for me in this area of history is The Brothers York by Thomas Penn. I very much enjoyed his book about Henry VII, Winter King. Penn is closer to the academic than the popular end of the history-writing continuum, which is fine by me as long as I have a reasonable foundational knowledge, and with a puff-quote from Hilary Mantel on the cover – “A gripping, sensational story” – what is there not to look forward to?

Some of the content above first appeared in a regular books, TV and films blog I wrote between 2020 and 2022.