Bohemian Rhapsody Film Review

Having now seen Bohemian Rhapsody for a second time, here’s an attempt to bring some order to a mad jumble of thoughts — what works and what doesn’t, whether the inaccuracies matter, whether it is fist-pumpingly brilliant or wince-inducingly awful, whether it is respectful of the Queen legacy, and above all whether it is a worthy addition to the Queen canon.

On the whole, I like the film. That was never a given. I am sure that nobody seriously expected a groundbreaking, genre-redefining, Oscar-sweeping piece of art — like the song Bohemian Rhapsody itself, say — but on the quality spectrum I was crossing my fingers for something more akin to The Doors than Spiceworld: The Movie. It’s short-sighted to wax lyrical about every last Queen product — this replica sixpence, that T-shirt, this vodka, that board game. Some things are high quality and worthwhile; others are mediocre and a bit naff. There Must Be More to Life Than This (the Queen & Michael Jackson version) is ordinary at best. I never particularly got into Roger’s band The Cross. I have not seen — nor do I intend doing — the We Will Rock You musical. Objectivity matters, even where ‘classic’ Queen is concerned and even more so in the case of post-Freddie and non-Queen projects.

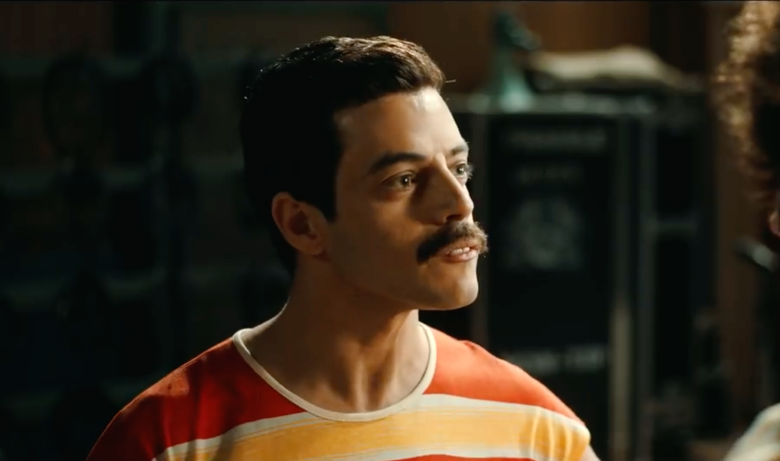

With regards to the film, I hadn’t paid too much attention to the various high-profile squabbles and sackings over the years. But with the publication last year of a series of appetite-whetting stills, followed by the drip-drip release of various trailers, and finally the recent publicity and hype, I was aware of an established consensus of sorts among fans before the film’s actual release: the four central acting performances (particularly Rami Malek) are amazing, it was said; the concert scenes are great; the attention to ‘authenticity’ is astonishing, though they take liberties with the ‘real’ story; plus a vaguer sense that it is going to be a rock ‘n’ roll rollercoaster ride, propelled along by an irresistible soundtrack.

Well, yes and no.

The soundtrack album was the first surprise. To be honest, I had expected Queen Productions Ltd to churn out another rehashed ‘greatest hits’ package. What emerged was a well-above-par release, with little nuggets of gold dotted throughout — from the previously unreleased guitar-rich version of Don’t Stop Me Now and the Queen-ified ‘Fox’ fanfare to the delightfully re-recorded Doing All Right and (best of all) the raw, thumping live Fat Bottomed Girls from Paris in 1979 — not even the version from the widely circulated bootleg video. Definitely promising.

The second ‘surprise’ — if surprise it is — was how many of the rumours were just plain wrong, yet another reminder to consume media tittle-tattle with a large helping of scepticism. Some at least of Sacha Baron Cohen’s version of history appears to be nonsense, though the script (if indeed there even was a script at that stage) will have undergone a million re-writes since his time. Among other canards, Brian’s first wife Chrissy does indeed appear in the film, as do all the ‘wives’ (for use of inverted commas, see below), and the accusations of ‘hetero-washing’ (ignoring or downplaying Freddie’s homosexuality) are way wide of the mark — indeed, scenes of men kissing men probably outnumber those of heterosexual canoodling.

The main weakness of the film for me is the balance of the script, a symptom of the lack of clarity about what sort of film this is trying to be. I wrote months ago on a fan forum that it was:

…far more important [for me] for the film to portray the power and impact of Queen’s live show.

In my mind, this was to be a film about Queen. But Bohemian Rhapsody purports to be a ‘biopic’ — a biographical film of Freddie’s life, focusing on the years from 1970 to 1985. In truth, it is a messy hybrid of the two. In part, it is a tongue-in-cheek whistle-stop re-enactment of key moments in the band’s history. Especially with the active involvement of Brian and Roger in the film’s production, Bohemian Rhapsody feels at times like a vehicle for (some of) the band’s greatest hits — a visual jukebox — and will doubtless be enjoyed by many for this very reason.

Bohemian Rhapsody is also an attempt at a deeper study of Freddie — flamboyant free spirit, creative genius, tortured soul. The film’s opening scenes take time to establish him as an awkward, restless outsider (a regular target for casual racism, for example), stumbling to realise vague dreams of stardom. Far from a fast-paced rollercoaster ride, I suspect that some will find these elements of the film ‘slow’. Above all, there are several scenes exploring the relationship between Freddie and Mary, the pivot around which the whole film revolves. Lucy Boynton as Mary is excellent throughout: the moment when she pretends to take a drink at Freddie’s insistence during a late-night phone call, thus signalling a release of sorts from his spell, is particularly affecting.

Comments by the historian Anthony Beevor, who wrote recently about war films, are interesting and relevant in relation to the film:

The real problem is that the needs of history and the needs of the movie industry are fundamentally incompatible. Hollywood has to simplify everything according to set formulae. Its films have to have heroes and, of course, baddies – moral equivocation is too complex. Feature films also have to have a whole range of staple ingredients if they are to make it through the financing, production and studio system to the box office. One element is the “arc of character”, in which the leading actors have to go through a form of moral metamorphosis as a result of the experiences they undergo. Endings have to be upbeat…

Ironically, the basic Freddie story does loosely conform to this by-the-numbers story arc: meteoric rise followed by downfall, before redemption (here during a Munich rainstorm — the pouring rain a familiar trope, symbolising cleansing and re-birth) and the grand Live Aid finale. However, the script is unable to handle the sheer quantity of source material, resulting in ridiculously contrived situations and jaw-dropping narrative leaps. Thus, Freddie meets the band and (separately) Mary at the same Smile gig — the exact same night that Tim quits to join Humpy Bong. Elsewhere, Freddie and John debut with the band on stage at the same time — the night, coincidentally, of the broken microphone stand. Most ridiculous of all (as Alexis Petrides points out in The Guardian), Freddie turns up unannounced on Jim Hutton’s doorstep to declare his love, and then reconciles with his (Freddie’s) father over tea and cakes — all on the same morning — before nipping across to Wembley Stadium to steal the show at Live Aid. A busy day indeed.

This brings us more generally to the thorny issue of historical accuracy and fidelity to the facts. Broadly speaking, events in the film fall into one of two periods of Queen history — ‘early’ and ‘late’. Within — and even across — these periods, the chronology is alarmingly fluid, and, as we were pre-warned, whole chunks of the Queen story are ignored, glossed over or turned upside down. A camper van, used for gigging up and down the country, is sold on Freddie’s initiative to pay for studio time: in reality, of course, Queen did almost the opposite, refusing to tread the usual ‘pub and club’ circuit — actually one of the things that immediately set them apart from run-of-the-mill bands at the time. John Reid arrives on the scene a couple of years early (around the time of the first album) and leaves about six years late (at the time Freddie was offered a solo deal by CBS): in reality he was the band’s manager for just three years. Rock in Rio acts as a backdrop for Freddie’s break-up with Mary — events probably eight years apart in reality. Before Live Aid, Roger exclaims that the band haven’t played live for years — helping to set up the dramatic finale but, of course, a fiction: the Works tour came to an end in Japan just two months before Live Aid.

Some of the inaccuracies are more puzzling, seemingly unimportant to the storyline. Freddie is shown smoking in ’75, several years before he actually started. Dominique Beyrand, Roger’s then girlfriend, is referred to as his wife (they only married in 1988). Journalists raise the spectre of AIDS at a press conference for the release of the Hot Space album, which would have been in 1982, a year before scientists had even formally identified the virus. Jim Hutton is working as a waiter at one of Freddie’s house parties when the two first meet; they actually met in a nightclub. And photo evidence may provide evidence to the contrary, but some of the costumes just don’t ring true — Brian’s orange Adidas top in the We Will Rock You scene, to name one. Trivial though these details are, they nevertheless sit uncomfortably alongside Queen official archivist Greg Brooks’ unwise assertion that “… the Fox team were obsessed with detail; getting every aspect of every scene perfectly right”. No, Greg; they obviously weren’t.

Two figures loom large in the background. The role of arch-villain, as had been well trailed, is assigned to Paul Prenter, the eminence grise, fuelling Freddie’s hedonistic lifestyle and — motivated by infatuation and greed — increasingly blocking all contact between Freddie and the Queen ‘family’, and between Freddie and Mary. Prenter’s real part in the Queen story is well known, but I have sympathy (again) with the critic Alexis Petrides, who argues that the demonisation of Prenter necessitates portraying the rest of the band as conventional, clean-living, sober chaps. Perhaps this is the reason why Dominique Beyrand is referred to as Roger’s wife — a clumsy attempt to juxtapose the band’s growing maturity and sense of responsibility with Freddie’s wild abandon (early scenes make clear the younger Roger’s fondness for partying). We see no wild Queen parties and there is no collective band meltdown in Munich, both of which are perhaps closer to the truth than what we see in the film.

Less expected was the portrayal of Jim Beach. In contrast to Prenter, he is a sober, steadying influence. Jim is an almost ubiquitous presence — during tricky negotiations with the record company, during a critical band reconciliation scene in his office, even during recording sessions, dutifully completing paperwork at a side-table. He is there in the background at band rehearsals for Live Aid when Freddie reveals his HIV status to the band (the implication being, of course, that Jim already knew). In a Jeeves-ish final twist, it is Jim who increases the volume on the mixing desk at Live Aid before Queen’s set — in reality, it was a sound guy called Trip Khalaf.

The on-stage scenes are good, though it would be going too far to say that they faithfully ‘copy’ Queen live. The lengthy Live Aid sequence is an exception; it is carefully recreated. The use of ‘live’ recordings works extremely well, and the actors’ miming is good, particularly Malek’s lip-synching. Again, some aspects of the live scenes are just fabrications: for example, each member of the band — even John! — is shown introducing themselves to the audience as Freddie holds his microphone horizontally. We already knew before the film came out about the placing of Fat Bottomed Girls early in their career: it is used to soundtrack a blistering first tour of the States, years before its actual release.

Some inaccuracies are no big deal — the lighting rig a cross between the ‘pizza oven’ and the ‘G2 razors’, Freddie throwing his leather jacket across the stage towards the crowd, dry ice during We Will Rock You. We knew about the crowdsurfing from the trailers, of course. How I wished this had found its way to the cutting-room floor. Alas, no. Jim Morrison used to jump into the crowd. Maybe for him it was spiritual, his way of connecting with the audience. Freddie was a showman and entertainer, glorying in his superstar persona, urging us in the midst of ‘70s recession and industrial decline to drink champagne for breakfast. He was not a crowdsurfer.

And what of the band performances? Rami Malek is indeed excellent. The ‘biopic’ format does not best serve Gwilym Lee, Ben Hardy and Joseph Mazzello, over-accentuating as it does Freddie’s role and importance, leaving their characters somewhat underdeveloped. I also struggled at first to reconcile what I saw on the screen with my own perceptions and preconceptions of my childhood heroes. Only on second viewing did I really warm to their performances. Gwilym Lee certainly captures Brian’s voice and mannerisms. The younger ‘Brian’, however, felt too carefree and jokey: I find it difficult to imagine Brian engaging in witty repartee. ‘My’ Brian is the epitome of solemnity — serious, studious and deeply thoughtful.

Mazzello brings out John’s quiet steadiness, though his facial expressions veer uncomfortably close towards gurning at times, and his on-stage ‘Deacy’ moves are a little over-exaggerated. Well done to Ben Hardy for nailing the Hammer to Fall drum parts. However, other than for his ‘Galileos’, non-Queen fans may wonder at Roger’s importance in the band. Of the four, his part seemed the most obviously underdeveloped, though he was involved with Freddie’s younger sister in the film’s funniest exchange:

ROGER: So Kash, what are you doing later?

KASHMIRA: Homework.

I also liked the irony around I’m In Love With My Car. Mocked by Brian and John in the film, it has outlasted pretty much every other non-single as a staple of the live set, as well as earning Roger hefty royalty cheques as the original Bohemian Rhapsody b-side.

How, then, to sum up Bohemian Rhapsody? At times preposterous and cheesy, overreaching in places and prone to missteps, drift and loss of direction. Yet also larger than life, irresistibly ambitious, often majestic and magnificent, and always, always totally compelling.

Rather like Queen, in fact. And rather like Freddie.

The image at the head of this article is from this webpage. It is credited to Kathryn S. Kuhar.

Great review. I think perhaps on my second viewing I would also be picking up on some of the things you did. However, we watch films (as we do bands) for entertainment, and I was certainly entertained

Thanks, Ian – and thanks for taking the time to reply. I watched the film at 11am on the day of release (there were about ten people in the cinema, I think) and then again a couple of days later. By then, I had read the main newspaper reviews (not flattering, in the main).

Since then, the popular acclaim from across the entire world has been quite incredible. I posted this on Facebook a couple of weeks later:

The reaction from friends (‘sensible’ Queen fans, not geeks like me) after seeing the film is overwhelming: ‘amazing’; ‘ brilliant’; ‘best film in ages’; ‘cried all the way through’. Queen’s continued ability to move people is astonishing and surely unprecedented in music.

Good read that pal! Angela and me enjoyed the film very much and agree with Lisas comment that an outsider to the real queen story would enjoy the film without bothering too much for the inaccuracies!

Thanks for taking the time to read it and provide feedback, pal – and glad you enjoyed the film.

I’m far from an expert on Queen, having only recently, seriously listened to them. I thoroughly enjoyed the film. The facts and true representations I wouldn’t really have an idea on, but the actors were fantastic. Funny but also quite emotional….I feel a second viewing is a must.

Glad to hear that you enjoyed it. People’s opinions about the film seem to be coalescing around three main judgements:

1. It’s great – especially the acting, the ‘live’ segments and the soundtrack. That’s the opinion of most members of the public.

2. Notwithstanding the above, the inaccuracies are a problem. That’s the opinion of some of the die-hards and some of the critics (who also don’t like the script).

3. By focusing on Freddie’s wild behaviour in the ’80s and painting the other three as saints, it gives the film a preachy, moralising, anti-gay tone. That’s the opinion of many liberal/leftie critics.