Books, TV and Films, August 2021

2 August

A first look at The Inspector Alleyn Mysteries, which is repeated regularly on one or more cable channels and dates from the mid-’90s. It is based on the books (which I have never read) by Ngaio Marsh. Series one episode one (as usual). It is not intended as a criticism to describe it as ‘as expected’; extended detective dramas were very much the in-thing following the trailblazing Inspector Morse in the ’80s and remain so today. It is Poirot-ish in its social setting and Morse-ish in terms of Alleyn’s awkwardness with women (in Alleyn’s case, one woman in particular). As always, Patrick Malahide is perfect as Alleyn, all refined manners and impeccably cut-glass accent. What a delightful contrast with his comic portrayal of Detective Sergeant Chisholm in Minder.

7 August

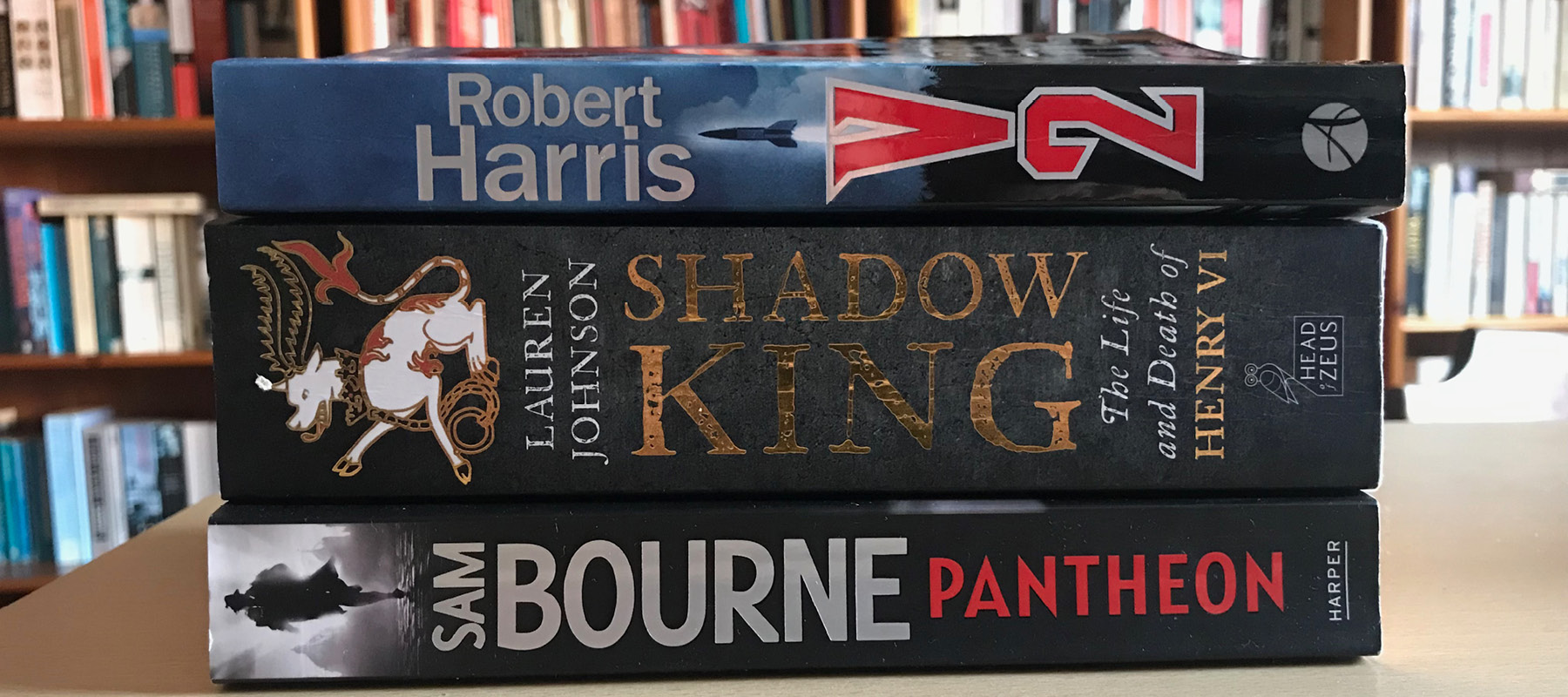

I always look forward to the publication of a new novel by Robert Harris. His previous, The Second Sleep, certainly didn’t disappoint — an intriguing stab at what-iffery, not unlike his very first novel Fatherland, which was set 20 or so years after a German victory in the Second World War. His latest effort, V2, is on more familiar Harris ground — weaving a compelling story out of real historical events, in this case the German V2 rocket programme and British efforts to foil it.

The ingredients I associate with Harris are here, principally a cleverly structured novel that keeps us turning the page (even though, like previous novels such as An Officer and a Spy and Munich, we already know the outcome) and helps to contextualise and humanise the cast of believable, human characters. Thus, the use of flashbacks to fill out the life story of the German scientist Rudi Graf and his longtime friend Wernher von Braun doubles as a history lesson in the German rocket programme.

As with his novel Enigma, mathematics, science and technology are an essential part of the story. Harris wisely spreads the technical detail across the book and keeps it relatively light and manageable for the non-specialist. His work is always carefully and thoroughly researched — a sine qua non of good historical fiction. One thing I did find odd. At several points he chooses to take off the mask of the novelist and reveal himself as a historian. Here’s an example, describing a V2 that hit a department store in Deptford, killing 160 people:

One young mother, with a two-month-old baby in her left arm, walking up New Cross Road on her way to the fabled saucepan bonanza, recalled forty years later “a sudden airless quiet, which seemed to stop one’s breath.”

Robert Harris, V2, page 38

Or this — the context in this case that several V2s were fired on the same day:

What happened to the third missile remains a mystery. It took off perfectly at 10.26am, but there is no record of its impact anywhere on the British mainland. Presumably it must have exploded in mid-air, perhaps during re-entry.

Robert Harris, V2, page 76

10 August

More fiction woven out of fact. This time it’s the film Red Joan, starring Judy Dench as an octogenarian widow arrested and charged with treason for giving the Russians secret information about the atomic bomb at the end of the Second World War. The film is loosely based on the real-life story of Melita Norwood, a high-value asset for the KGB who passed on classified work which helped the Soviet Union to develop an atomic bomb earlier than they otherwise would have done.

Judi Dench is, of course, wonderful in a role that reminded me at times of the part she played in Philomena — a woman in later life confronting her past and reacting in (to me, anyway) unexpected ways: Philomena is prepared to forgive the Catholic Church; Joan, once publicly exposed as a spy, is defiant in defence of her actions, believing them to have helped prevent a third world war.

Also excellent is Sophie Cookson as the young Joan Smith, a physics student at Cambridge in the ’30s who goes on to work on Britain’s top-secret atomic bomb development project. Like the excellent Hidden Figures with racism, the film lays bare the sexism — both structural and casual — of the day. Also interesting is its depiction of the young communists of the time, some of whom make the journey from youthful idealism, borne of a horror of war and disgust at the ugliness and wastefulness of capitalism, to fanatical Stalinists, prepared to sacrifice all — including friends and family — for Moscow. Philby, Burgess, Maclean, Blunt and Cairncross all attended Cambridge in the ’30s.

11 August

My interest in the Middle Ages continues, as do my belated — and somewhat haphazard — efforts to fill the enormous gaps in my knowledge of medieval history. In the last year or so I have read a biography of Elizabeth I by Anne Somerset and an excellent account of Henry VII’s life by Thomas Penn. Dan Jones has a big book coming out in September, which looks to be highly ambitious in scope. In the meantime, and continuing to work backwards, there is a 2019 biography of Henry VI called Shadow King by Lauren Johnson. I am hoping that she will prove a trusty guide through the endless and frequently baffling dynastic rivalries of the fifteenth century.

16 August

I finally watched The ABC Murders, the three-part Hercule Poirot drama shown on the BBC at Christmas. Based on advance publicity I very much had my doubts — John Malkovich as Poirot?! No moustache?! — so I am delighted to say that it was a gripping and thoroughly excellent reworking of Agatha Christie’s 1936 novel.

The ABC Murders was, I think, the first of the long-form ITV Poirot dramas that I watched back in the ’90s. This is another radical reimagining of Poirot (the other being Kenneth Branagh’s recent swashbuckling Poirot on the big screen in Murder on the Orient Express), far more haunted than the David Suchet incarnation, at least in the latter’s early series (the ITV dramas became considerably darker from series nine onwards after the original writing-production team left).

Poirot is a faded star, his career effectively over. In place of fame and celebrity is ridicule and suspicion. There is no Hastings, no Miss Lemon. Inspector Japp drops dead in the opening scenes and Poirot is forced to work with the deeply hostile Inspector Cromer (played by a barely recognisable Rupert Grint) who reveals that Poirot has himself been under investigation by the authorities, who discovered that he had lied about his past when he arrived in England as a refugee from Belgium. The events of the First World War continue to haunt Poirot. In the background, too, is the growing menace of xenophobia (depicted as increasing popular support for fascism), a none too subtle nod by the writers in the direction of Brexit, one assumes.

23 August

Lauren Johnson’s Shadow King: The Life and Death of Henry VI has been hugely enjoyable. It is well written and (importantly for me) user-friendly for the non-specialist. I have always steered well clear of the fifteenth century in general and the Wars of the Roses in particular, put off as much by the baffling family trees as anything else. Johnson offers frequent reminders of who people are, their titles, former titles, familial connections etc, as well as a comprehensive Who’s Who as an appendix. And rather like Dan Jones’ very enjoyable The Plantagenets, the writing has an engaging narrative drive to it, with chapters typically ending on a cliffhanger.

My first impressions of Henry are of how unorthodox he was. As a king utterly out of step with the medieval view of monarchy, he seems to have had much more in common with Richard II, who was also deposed and murdered, than with his warrior-king father Henry V. In an age when ‘rules’ and codes of behaviour were all-important, it is no surprise that his actions (and inactions) caused such discombobulation.

Reading about the younger Henry’s unwillingness to follow the accepted rules put me in mind of President Woodrow Wilson and his attempts to remake the international order at the end of the First World War by ditching the old system of power politics and alliances in favour of collective security and a League of Nations. There is also a parallel of sorts with President Trump, a blundering amateur who disregarded almost all foreign policy norms and conventions, believing that he could do personal deals that would solve age-old problems and end age-old rivalries. In reality, his meddling did more to stoke than to solve conflict.

Henry also resembled Richard II in displaying a fatal incompetence at crucial moments. For all that Henry’s mindset might suit the modern day, it was not acceptable in a medieval monarch. A man of honourable intentions, he was undermined by indecision and by an unwillingness to be sufficiently ruthless at key moments of his reign. He was deeply pious and equally deeply naïve. Time and again he chose to accept the solemn oaths and declarations of loyalty of his rivals, only to be later betrayed.

And despite being schooled in kingship from a young age, he came to depend on others, to the point that whoever controlled him controlled the kingdom — a recipe for disaster. Again, there is a parallel with the disastrous presidency of Trump: what to do when the top person is simply not up to the job. Henry VI was not just a poor decision-maker, he also suffered serious bouts of mental illness.

Having praised Johnson’s writing, one thing I didn’t like is the inclusion of seemingly spurious detail. Take this, just one example from many, describing the loading of a ship with treasure at the port of Sandwich in 1432:

In the darkness of the harbour mouth, lights flashed and glared. Above the low creak of ships’ timbers, men’s voices punctured the frosty stillness of the night. Occasionally there came a low thump of coffers hitting the decking. A groan. A cricked back. And then the great chests lifted again, edged closer, step by heavy step, towards the tilting flank of a ship called Mary of Winchelsea. [ch 7]

Lauren Johnson, Shadow King: The Life and Death of Henry VI, from chapter 7

All very atmospheric but more the sort of thing I would expect to read in a Hilary Mantel novel. The footnote attached to the paragraph as a whole refers to a biography of Cardinal Beaufort (whose treasure it was) and presumably relates to a fact about the value of the cargo, Beaufort’s entire wealth.

28 August

I am finishing the month with another Sam Bourne page-turner. Jumping ahead of sequence (I don’t yet have a copy of 2008’s The Final Reckoning) this is Pantheon, published in 2012. Two minor coincidences here. The setting is the Second World War, the same as Robert Harris’s V2 [see above]. And the backstory is set amidst the left politics of the 1930s, anti-fascism and the Spanish Civil War, as was Red Joan [see above also].

This is very unlike the other Sam Bournes I have read, much more of a slow-burner. The first half of the book seems to be a (fairly) conventional story of a man searching for his wife and child, with just occasional hints of something more at play, such as his feeling that he is being watched. Our suspicions are finally confirmed in chapter eighteen when we learn that he has “stumbled into something much bigger than you realise. Bigger and more dangerous.” The chapter ends with him catching a peek at some photographs: “It took him a while to absorb what he had seen. Once he had, the images both shocked him — and explained everything.”