Ralph Miliband Biography Review

A strength of the book is that, throughout, the reader senses that judgements made are balanced and fair, sympathetic to the man but not blinkered to his mistakes, failures and personal foibles — not least a tendency to irascibility and impatience towards others as well as moments of self-doubt and, on occasion, fierce self-criticism.

Diogenes

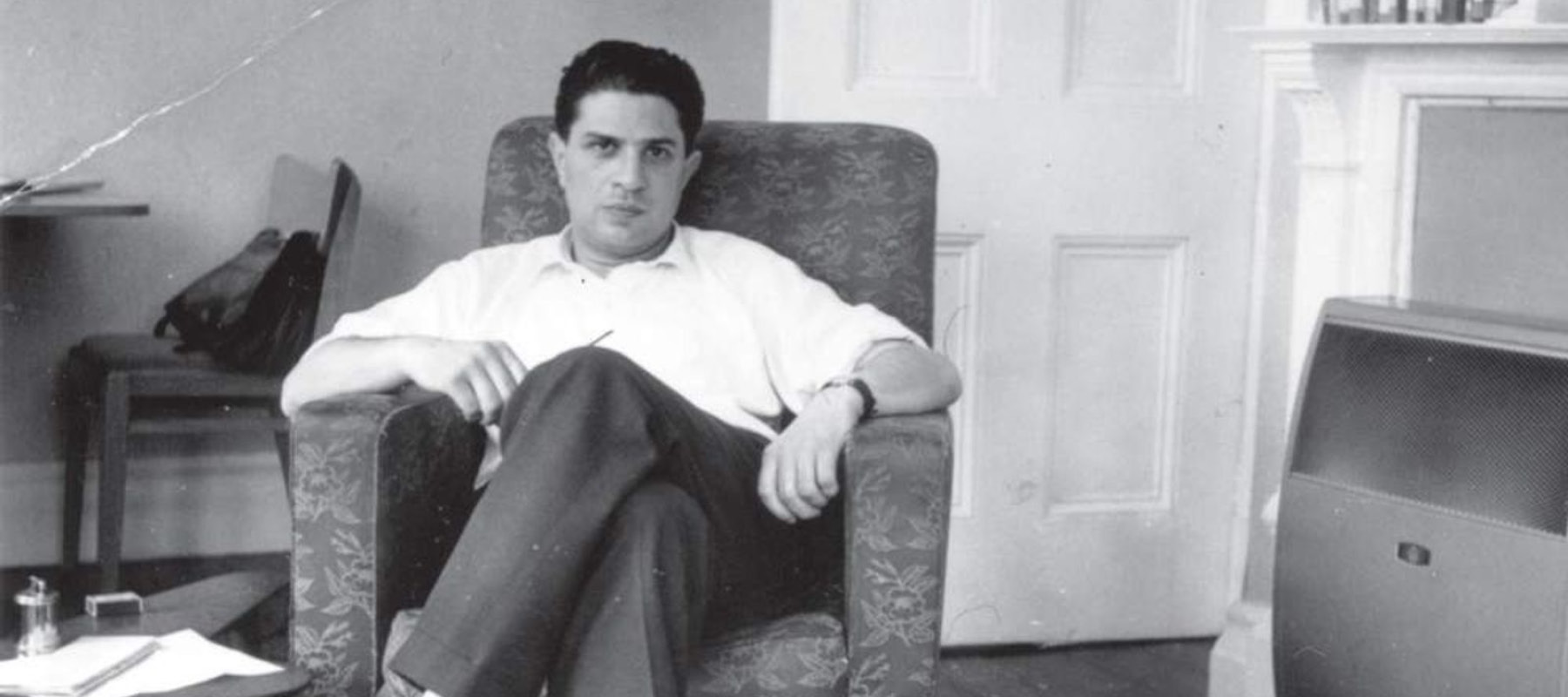

Ralph Miliband and the Politics of the New Left by Michael Newman

Twenty years on, I can still vividly recall scanning the shelves of the university library — me, an eager second-year history/politics undergraduate — in search of a Marxist critique of fascism and happening across a book by Nicos Poulantzas. Three hours, one much-thumbed dictionary, two headache tablets and five pages later, I gave up. My next encounter with the World of Marx was Professor David McLellan’s 1973 biography of Marx himself: well researched and worthy, to be sure, but dense and daunting for the uninitiated. Finding Ralph Miliband was something of a revelation, therefore, for here was a academic — what’s more, an avowedly Marxist academic — with both the ability and the willingness to elucidate Marxist ideas in an accessible way.

Miliband’s most influential book — The State in Capitalist Society — transformed the political sciences in the 1970s and provoked a famous debate with the aforementioned Poulantzas, in part concerning the role and importance of abstract theorising. Poulantzas championed an ultra-theoretical school of Marxism that shunned empiricism and seemed to glory in abstruse theorisation. For these ‘Althusserians’, Marxism had its own discourse, purposely distinct from much of the terminology and assumptions of ‘bourgeois’ debate and thus intelligible only to those who could decode its arcane meanings. Miliband, on the other hand, always sought to test even the most basic of assumptions within the Marxist tradition with reference to the ‘real world’. Moreover, Marxism was much more than a theory for Miliband: it was a guide to action.

As Michael Newman’s book shows, Miliband was an academic, a teacher but, above all, a committed socialist, happiest when he felt he was contributing to the advancement of the left. Thus, in Parliamentary Socialism — the book that secured his international reputation in 1962 — by analysing the reasons for the Labour Party’s failure to implement ‘socialism’, he was implicitly offering a guide to future action. Apart from a brief flirtation with the Bevanites in the 1950s and the Bennite left in the 1980s, Miliband kept his distance from the Labour Party, highly sceptical as he was of its efficacy as an agent of socialist change. He spent his adult life in the ultimately fruitless search for a suitable vehicle to secure a political breakthrough, wedded to the belief that only a class-based political party could do so.

Born in 1924 into a Jewish home, Miliband’s political consciousness was awakened by the Nazi menace in the late-1930s. Though the death camps cast a dark shadow over his childhood and youth, Miliband was one of a number of European refugees who escaped the clutches of the Nazis, finding sanctuary in Britain and going on to form the nucleus of a radical intelligentsia that helped shape the cultural, academic and — to an extent — political landscape of the 1960s and early-70s. Indeed, Miliband lived through a remarkable, if turbulent and ultimately unsuccessful, period for the left. This book is in part, therefore, also a history of the British left from the twin crises caused by de-Stalinisation and the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956 through the upheavals of 1968 to the challenge of Thatcherism and the collapse of Soviet-type communism.

In writing the book, Newman had access to family, friends and Miliband’s own letters and papers, including a diary and notes made in 1983 for a planned but never completed autobiography. Newman uses this impressive selection of primary source material to paint a convincing portrait of the ‘private’ man as well as the more familiar public figure. His style is — like Miliband’s own — both accessible and, on the whole, eminently readable. A strength of the book is that, throughout, the reader senses that judgements made are balanced and fair, sympathetic to the man but not blinkered to his mistakes, failures and personal foibles, not least a tendency to irascibility and impatience towards others as well as moments of self-doubt and, on occasion, fierce self-criticism.

On the other hand, given the breadth of Miliband’s interests and concerns, judicious editing might have resulted in a more balanced book. Several extracts from Miliband’s work are quoted verbatim and at excessive length. Elsewhere, 13 pages are devoted to ‘the troubles’ at the LSE in 1968 and an entire chapter to his involvement in a campaign for academic freedom. This particular reader frankly hoped for less description and rather more in the way of reflection on matters such as Miliband’s position on academic freedom (which was somewhat inconsistent), his widening disagreements with others on the New Left vis-à-vis the nature and role of the working class by the 1980s and the wisdom of his wish to see a Marxist party of a non-dogmatic nature filling the void between the Labour Party and the Leninist CPGB (which he held in little short of contempt). Tightly written summaries of Miliband’s ideas and actions and relevant narrative would have given Newman more space for his own analysis, commentary and judgements.

This review relates to the edition published in 2002 by Merlin Press. It was uploaded to Amazon in 2004.